Fighting impunity should be priority for Mexican government

By Carlos Lauría

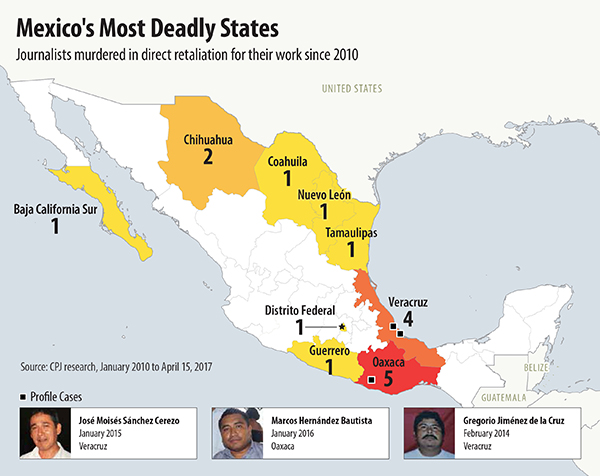

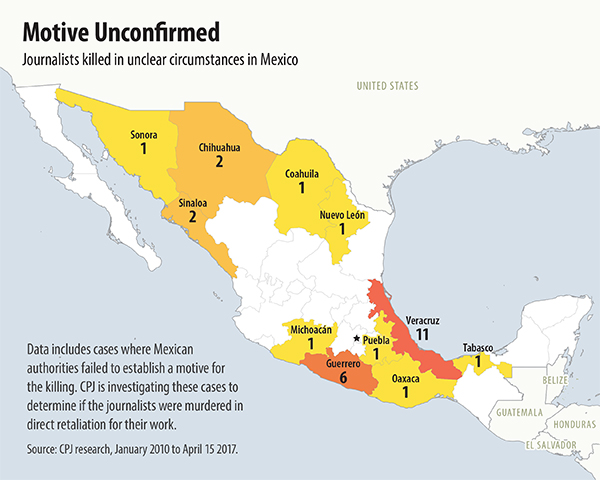

Violence tied to drug trafficking and organized crime has made Mexico one of the most dangerous countries in the world for the press. Since 2010, CPJ has documented more than 50 cases of journalists and media workers killed or disappeared. But in nearly every case of a journalist murdered in direct retaliation for their work, justice remains elusive and impunity continues to be the norm.

Mexico’s impunity rating has more than doubled since 2008, when CPJ released its first impunity index. But despite publicly condemning violence against journalists, President Peña Nieto, who has just over a year left in office, has done little to ensure his legacy will be one of ending this endemic problem.

For more than a decade, CPJ’s advocacy efforts and engagement with the Mexican federal government during the successive administrations of presidents Vicente Fox, Felipe Calderón, and Peña Nieto have led to the creation of a special prosecutor’s office for crimes against freedom of expression (FEADLE), the establishment of a federal protection mechanism for journalists and human rights defenders under threat, and the enactment of a constitutional amendment in 2013 that gives federal authorities broader jurisdiction to prosecute crimes against freedom of expression.

However, convictions in journalists’ murders are infrequent and when they do occur—like in the case of a former police chief sentenced in March to 30 years in jail for killing Oaxacan reporter Marcos Hernández Bautista, whose case is covered in this report—they are often limited to the perpetrator and authorities fail to establish a motive.

By not establishing a clear link to journalism or providing any motives for the killings most investigations remain opaque. This lack of accountability perpetuates a climate of impunity that leaves journalists open to attack.

CPJ’s research for this report into the murders of three journalists, including Hernández, highlights the failings of a judicial system that is both dysfunctional and overburdened. But it also shows that strong political will is needed from the federal government to prioritize impunity in cases of attacks against the press and to guarantee journalists’ safety.

Two of the cases—those of Gregorio Jiménez de la Cruz and José Moisés Sánchez Cerezo—took place in Veracruz state, one of the world’s most lethal regions for the press. Between 2010 and 2016—during former governor Javier Duarte de Ochoa’s administration—at least six journalists from Veracruz were murdered in direct retaliation for their work and three more went missing. CPJ is investigating the cases of at least 11 others to determine if they were killed for their journalism. Already this year in Veracruz, one journalist was shot dead and an editor was seriously wounded. CPJ is investigating to determine if the attacks are related to their work.

Duarte resigned as governor 48 days before the end of his term in October 2016 amid allegations of embezzlement and links to drug cartels, according to press reports. The governor, who critics say contributed to a climate of impunity that allowed for widespread murders, denied the allegations but disappeared before authorities could investigate him. As of April 17, Duarte was due to be extradited to Mexico after being arrested in Guatemala in a joint Interpol and Guatemalan police operation that used intelligence provided by the Mexican authorities, according to reports.

Justice denied

Structural flaws in the Mexican criminal justice system mean that suspects may have been identified, arrested, or even convicted, but the investigations cannot be fully solved and motives are still not entirely established. The cases covered here show not only the violence and threats the Mexican press faces, but also how delays and inefficiencies in the mechanisms created to protect journalists and fight impunity impact justice. In Sánchez’s case for instance, police identified a mastermind—a city mayor—but bureaucratic delays allowed him to evade justice. Jiménez’s case is an example of how Veracruz authorities consistently refuse to acknowledge a connection between a victim’s journalism and murder, and try to frame it as a regular crime.

Mexican administrations, from former presidents Fox and Calderón to Peña Nieto, have all publicly recognized that violence against the press is an issue of national and international concern. All three condemned killings and impunity. But so far, their efforts to address the problem have been insufficient. The pursuit of justice has failed categorically.

Despite Peña Nieto enacting the complementary laws to implement the constitutional amendment that empowers authorities to prosecute crimes against freedom of expression, the level of violence remains high. The lack of convictions in crimes against the press is inhibiting citizens, including reporters, to fully exercise the right to freedom of expression, guaranteed in Articles 6 and 7 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States.

Many journalists say the mechanisms set up to address impunity and violence don’t go far enough. FEADLE is criticized for securing justice in only three cases. And, although the protection mechanism is set up to respond within three hours of being notified of a serious threat, journalists who use it told CPJ the emergency measures don’t go far enough. Risk assessments, which are carried out in Mexico City, lack the expertise of regional specialists who could advise on needs specific to their location, and reporters are reluctant to trust authorities with their safety.

Peña Nieto and his government are running out of time to resolve these problems. His administration has been beset by corruption scandals and a poor human rights record, including an inability to solve the 2014 forced disappearance of 43 students in the state of Guerrero. If justice does not prevail before his term ends however, Peña Nieto risks leaving a legacy of endemic impunity.

Localized violence

Another factor highlighted by this report is how the climate of violence makes it dangerous for local journalists to investigate the murders of their colleagues. As in other dangerous countries, Mexican reporters are on the front lines of violence and are usually unable to conduct in-depth investigations without serious risk to their own lives. CPJ research of killed journalists worldwide since 1992 shows that in nearly nine out of 10 cases the victims were covering news in their home country.

When CPJ traveled to Veracruz and Oaxaca in January, it relied on local reporters to help conduct interviews and meet with journalists, press groups, relatives of the murdered journalists, and officials. Miguel Ángel Díaz, editorial director of Plumas Libres in Xalapa, Veracruz, and Pedro Matias, Oaxaca correspondent for the newsweekly Proceso and the website Página 3, contributed greatly to the research and facilitated critical logistical support. At same time, collaborating closely with CPJ should help provide these local journalists with a measure of safety in reporting on the cases of murdered colleagues.

Breaking the cycle of impunity in crimes against the press is the main challenge the federal government faces to restore faith in the judicial system. Reforms to mend the deficiencies of a system that grants impunity for journalists’ killers are vital, but any change will be impossible without the full political will of the current administration. The creation of new prosecutorial bodies, the implementation of protection mechanisms, and the enactment of legal reforms are limited by a lack of strong political will to ensure that these measures succeed. If Mexico is seriously committed to addressing impunity, solving these crimes and ensuring the safety and protection of journalists must become a priority in Peña Nieto’s national agenda.