In record year, China, Israel, and Myanmar are world’s leading jailers of journalists

- English

In This Report

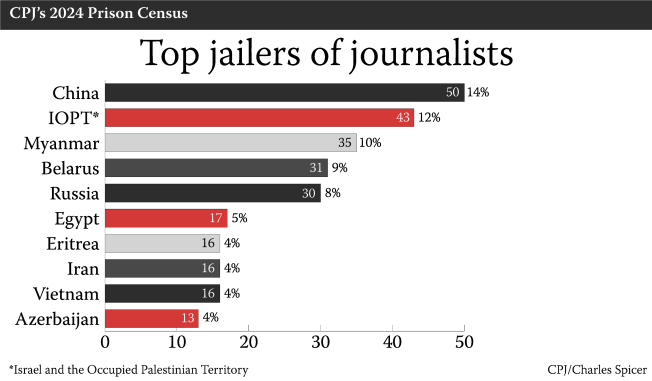

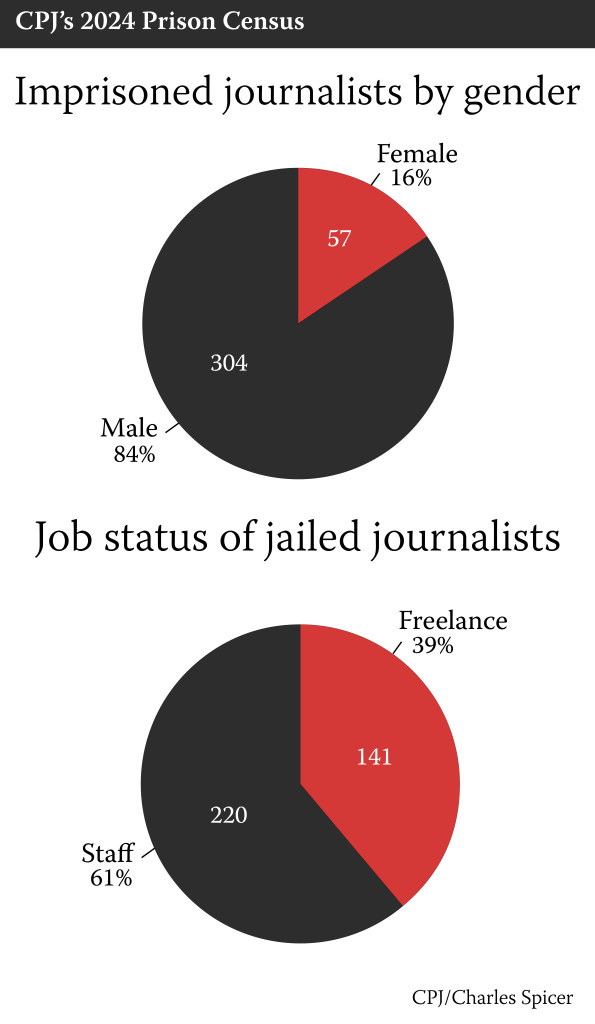

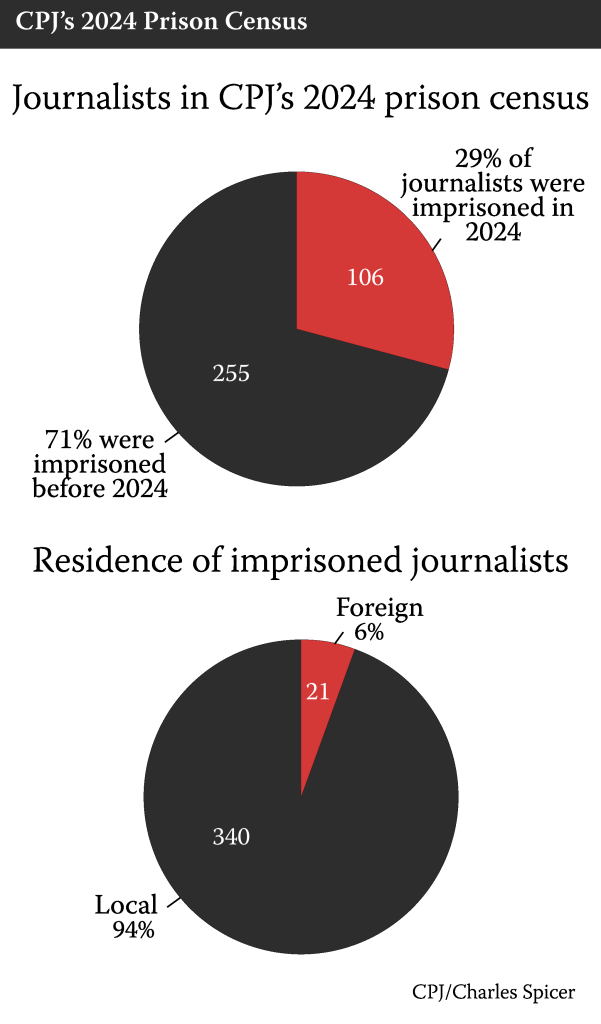

China, Israel, and Myanmar emerged as the world’s three worst offenders in another record-setting year for journalists jailed because of their work, the Committee to Protect Journalists’ 2024 prison census has found. Belarus and Russia rounded out the top five, with CPJ documenting its second-highest number of journalists behind bars – a global total of at least 361 journalists incarcerated on December 1, 2024.

While that number falls slightly below the global record set in 2022, when at least 370 journalists were imprisoned in connection with their work, CPJ recorded unprecedented totals in several countries including China, Israel, Tunisia, and Azerbaijan. The primary drivers of journalist imprisonment in 2024 – a year that saw more than 100 new jailings – were ongoing authoritarian repression (China, Myanmar, Vietnam, Belarus, Russia), war (Israel, Russia), and political or economic instability (Egypt, Nicaragua, Bangladesh).

China, Myanmar, Belarus, and Russia routinely rank among the top jailers of journalists. Israel, a multiparty parliamentary democracy that rarely appeared in CPJ’s annual prison census before the 2023 start of the war in Gaza, catapulted to second-place last year as it tried to silence coverage from the occupied Palestinian territories.

Yet while circumstances varied from region to region and country to country, all jailers followed a dispiritingly similar tactical playbook.

Key 2024 trends

Arbitrary detention

Across the globe, authorities in multiple countries routinely violated due process procedures, including arbitrarily detaining members of the media even after they’d served their sentences or unjustly holding them for extensive periods without trial.

Egypt used enforced disappearances – a crime under international law – to intimidate and silence journalists before formally detaining them and violated its own criminal procedure law with a two-year extension of the incarceration of Egyptian-British blogger Alaa Abdelfattah, who should have been released in September. In Saudi Arabia, cartoonist Mohammed al-Ghamdi (Al-Hazza) was sentenced to 23 years as he was preparing to leave prison after serving his original six-year sentence. In China, it remains unclear whether five of the seven Uyghur students arrested with scholar and blogger Ilham Tohti were released when the last of them completed their sentences more than two years ago.

Alaa Abdelfattah in an undated image obtained by Reuters on November 8, 2022. (Photo: Reuters/Omar Robert Hamilton)

Trial delays were another punitive measure. In Hong Kong, media entrepreneur Jimmy Lai has been held since December 2020 amid repeated postponements of his trial on national security charges, which could see him jailed for life. His son Sebastien told CPJ that prison conditions are “breaking” his father’s body, raising concerns about the prospect of the 77-year-old spending another summer in the harsh conditions and stifling heat of a Hong Kong prison.

In Guatemala, José Rubén Zamora spent more than 800 days in arbitrary detention before he was released to house arrest in October. But he still risks being returned to jail after an appeals court overturned that ruling in November, as he awaits a long-delayed retrial on money-laundering charges widely condemned as retaliation for his journalism. In Angola, Carlos Alberto was still in jail on December 1 despite becoming eligible for parole the previous month after his three-year sentence for criminal defamation was reduced to 27 months under a 2022 amnesty law.

The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has found that Lai, Zamora, Eritrean journalist Dawit Isaak, Rwandan journalist Théoneste Nsengimana, and Palestinian journalists Mohammad Badr and Ameer Abu Iram are among those being held in violation of international law. (CPJ has repeatedly advocated on behalf of these journalists.)

Ethnic discrimination

Journalists from a range of marginalized ethnic groups were targeted across the globe. Almost half of those held in China are members of the mostly Muslim Uyghur minority; two are ethnic Kazakhs. All detained by Israel on the day of CPJ’s census are Palestinian. Two of the eight journalists imprisoned by Tajikistan are members of the long-persecuted Pamiri minority. One, Ulfatkhonim Mamadshoeva, is serving 20 years after authorities accused her of organizing Pamiri protests in the country’s eastern Gorno-Badakhshan autonomous region.

At least 10 Kurdish journalists, the Middle East’s fourth-largest ethnic group, are also in prison: five in Turkey, two in Iran, and three in Iraq. Russian occupiers have targeted the Crimean Tatar community in Ukraine’s Crimea. In Afghanistan, the Taliban detained reporter Mahdi Ansary, a member of Afghanistan’s persecuted Hazara community, in October 2024.

Harsh sentences

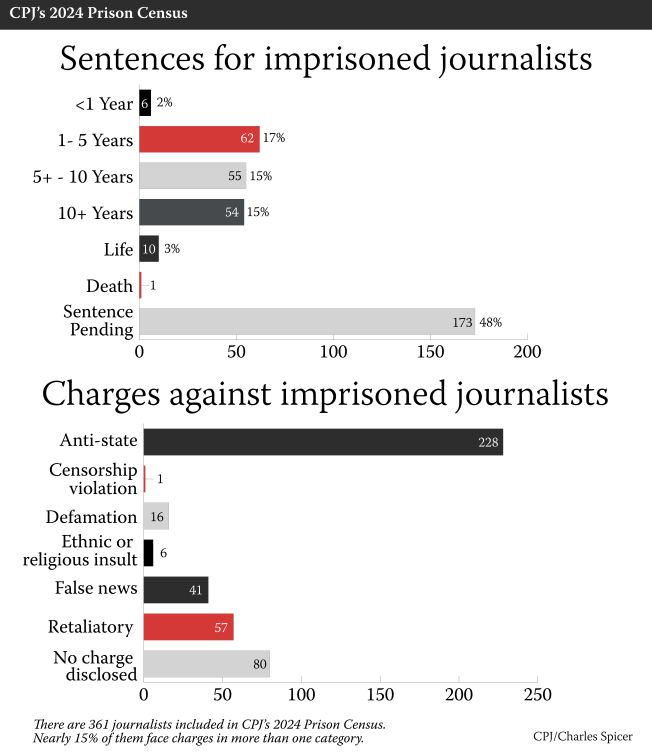

Many of the journalists in CPJ’s 2024 census have been sentenced to spend significant parts of their lives in jail. Ten have been sentenced to life; one has been sentenced to death.

A total of 54 are serving more than 10 years; 55 between five and 10 years, and 62 between one and five years.

Many of the journalists in CPJ’s 2024 census have been sentenced to spend significant parts of their lives in jail.

In Senegal, a CPJ investigation found that René Capain Bassène was jailed for life for a crime that witnesses said he couldn’t have committed. In Myanmar, Shin Daewe – denied legal representation during her trial by a secret military tribunal – received a life sentence in 2024 on charges of illegal possession of an unregistered drone, a criminal offense under the country’s Anti-Terrorism Law. In China, Tohti, founder of a Uyghur news site, has served more than 10 years of his life sentence. In Turkey, Hatice Duman – one of four journalists in the country sentenced to life – has spent more than 20 years in jail in spite of a 2019 Constitutional Court finding that her right to a free trial had been violated. Her retrial is ongoing.

In China, a Beijing court issued Yang Hengjun a suspended death sentence in February 2024, which could be commuted to life imprisonment after a two-year period of good behavior. Yang, a former Chinese diplomat turned blogger and political commentator, frequently posted commentary on social media about U.S.-China relations, espionage, and political reform.

Criminalization of journalism

More than 60% of the journalists in CPJ’s 2024 census – 228 – are imprisoned under a range of broad anti-state laws frequently used to stifle independent voices.

Often-vague charges or convictions for terrorism or “extremism” make up a significant portion of those cases in countries including Myanmar, Russia, Belarus, Tajikistan, Ethiopia, Egypt, Venezuela, Turkey, India, and Bahrain. These accusations are commonly leveled against ethnic minority reporters whose work focuses on their communities, with authorities routinely citing journalists’ contact with militant groups – often necessary for news coverage – as evidence of membership in those groups.

Other frequently used charges are incitement, defamation, and false news.

More on imprisoned journalists

- Tunisia uses new cybercrime law to jail record number of journalists

- How CPJ helps jailed journalists

- CPJ finds flaws, inconsistencies in murder conviction of Senegalese journalist René Capain Bassène

- Interactive map: Attacks on the Press

Worst Offenders

#1 China

China has routinely appeared in CPJ’s annual prison census as one of the world’s top jailers of journalists. The 50 recorded as being behind bars on December 1, 2024, are likely an undercount given Beijing’s pervasive censorship and mass surveillance that often leaves families too intimidated to talk about a relative’s arrest. Their circumstances are a stark reflection of China’s intolerance for independent voices.

CPJ’s 2024 data indicates that Beijing is ramping up the use of anti-state charges to target journalists. Chinese journalists Dong Yuyu, detained in February 2022 while having lunch with a Japanese diplomat, and Sophia Huang Xueqin, in custody since September 2021, were sentenced in November 2024 to seven and five years respectively on charges of espionage and “inciting subversion of state power.” Chinese independent journalist Li Weizhong, arrested in October 2024, is also being held on allegations of inciting subversion of state power.

The 50 recorded as being behind bars are likely an undercount given Beijing’s pervasive censorship and mass surveillance.

In Hong Kong, the media faced growing pressure. Journalists detained in 2020 and 2021, as authorities’ cracked down on the city’s pro-democracy movement, remain in jail amid repeated legal delays. In addition to Lai, six journalists and media executives from Lai’s Next Digital Limited and now-defunct Apple Daily newspaper – Lam Man-chung, Fung Wai-kong, Yeung Ching-kee, Cheung Kim-hung, Ryan Law Wai-kwong, and Chan Pui-man – have spent more than three years behind bars as they await sentencing on charges of conspiring to collude with foreign powers.

In China’s north-western region of Xinjiang, where Beijing has been accused of crimes against humanity for its mass detentions and harsh repression of Muslim groups, two Uyghur journalists, Qurban Mamut and Mirap Muhammad, appear for the first time in the 2024 census after CPJ research determined that their incarceration was linked to their work.

Mamut, the former editor-in-chief of the Uyghur-language magazine Xinjiang Civilization, is serving a 15-year sentence on charges of committing “political crimes” after he went missing in 2017. His son, Bahram Sintash, told CPJ that it took until 2022 to confirm that his father was alive and where he was imprisoned. Muhammad, a Uyghur blogger whose articles included sensitive topics such as Uyghur and human rights issues, has been held incommunicado since his arrest in 2018 on accusations of “illegally providing intelligence to a foreign body.”

#2 Israel

CPJ documented 43 Palestinian journalists in Israeli custody on December 1, 2024 – more than double the number held in the 2023 census, when Israel ranked for the first time as one of the world’s worst jailers of journalists.

While Israel has appeared several times on CPJ’s annual prison census, the arrests in the wake of the October 7, 2023, Hamas attack on Israel are its highest since CPJ began keeping records in 1992. It is the first time Israel has ranked as the world’s second-worst jailer of journalists.

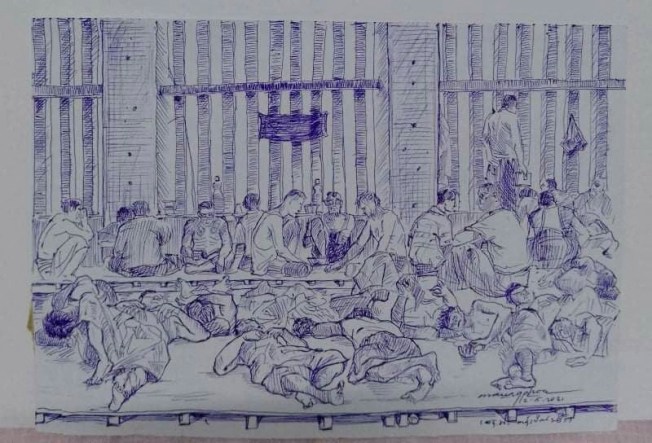

Palestinian prisoners captured in the Gaza Strip by Israeli forces are seen at a detention facility in late 2023 on a military base in southern Israel. (Photo: Breaking The Silence via AP)

At least 10 journalists were held in the occupied West Bank under a policy of administrative detention, which allows a military commander to detain a person without charge on the grounds of preventing them from committing a future offense. Detention can be extended an unlimited number of times.

Palestinian prisoners in Israeli prisons and detention facilities are subjected to “inhuman conditions” that include “frequent acts of severe, arbitrary violence; sexual assault; humiliation and degradation; [and] deliberate starvation.”

In Gaza, journalists are also held under the Incarceration of Unlawful Combatants Law, which, like administrative detention, allows Israel to hold detainees for long periods of time without charge and with limited access to legal counsel. According to Israeli human rights group B’Tselem, Palestinian prisoners in Israeli prisons and detention facilities are subjected to “inhuman conditions” that include “frequent acts of severe, arbitrary violence; sexual assault; humiliation and degradation; [and] deliberate starvation.”

Lawyers who have visited some of the detainees told CPJ that Israeli investigators informed the journalists that they were arrested because they had contacted or interviewed people Israel wanted information about.

The journalists’ detentions are symptomatic of Israel’s broader effort to prevent coverage of its actions in Gaza. This includes barring foreign correspondents from entering the territory and banning Qatari-based broadcaster Al Jazeera from operating in Israel and the occupied West Bank under a wartime law that allows the Israeli government to shut down a foreign outlet it deems a threat to national security.

#3 Myanmar

Myanmar held 35 journalists at the time of CPJ’s 2024 census. All were taken into custody on anti-state allegations after a 2021 military coup ousted a democratically elected government. The junta has cracked down on Myanmar’s media, incarcerating and sentencing dozens of journalists among the more than 28,000 political prisoners detained since it seized power.

While fewer journalists were held in 2024 than the peak of 42 in the year after the coup, the decline doesn’t reflect any softening in the military’s criminalization of independent journalism or its intolerance of dissent. Jailed members of the media are typically tried by military tribunals, denied legal representation, and given multi-year sentences under broad anti-state laws such as terrorism, false news, or incitement.

Of the eight sentenced in 2024, two – Myo Myint Oo and Shin Daewe – were jailed for life, and a military court sentenced reporter Aung San Oo to 20 years on terrorism charges. (Shin Daewe’s sentence was reduced to 15 years as part of a broader prisoner amnesty in January 2025.) Also still serving 20 years on charges including sedition is photojournalist Sai Zaw Thaike, who was arrested in May 2023 while covering the aftermath of a cyclone that killed more than 140 people, including many members of the persecuted and displaced Rohingya minority.

#4 Belarus

With 31 journalists in jail on December 1, 2024, Belarus is the worst jailer in Europe and Central Asia for the second consecutive year. Despite several waves of presidential pardons by Aleksandr Lukashenko, which included three members of the press, Belarusian journalists are continually harassed, detained, and sentenced to years in prison, most often over their work for media outlets that authorities have labeled as “extremist.”

With 31 journalists in jail on December 1, 2024, Belarus is the worst jailer in Europe and Central Asia for the second consecutive year.

The Belarusian government continued to retaliate against journalists who covered protests calling for Lukashenko’s resignation after his disputed 2020 election. Five journalists detained in connection with those demonstrations are serving sentences of 10 years or longer. Those held in 2024 include former video reporter Yauhen Nikalayevich, who left Belarus and stopped practicing journalism in 2020. Nikalayevich was arrested when he returned to the country in 2024 and is serving an 18-month sentence for “organizing or participating in gross violations of public order.”

Belarus also continued to harass journalists beyond its borders, initiating criminal proceedings against several exiled journalists, and searching the Belarusian homes of others who have left the country. Belarusian filmmaker and journalist Andrey Gnyot spent a year in detention in Serbia while Belarusian authorities tried to extradite him on tax charges.

#5 Russia

Russia held 30 journalists behind bars at the time of CPJ’s census. Almost half are Ukrainian, victims of Russia’s 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea and Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Ukrainian journalist Viktoria Roshchina died in Russian custody in September – a grim reminder of the plight of journalists detained incommunicado in Russian-held territories on undisclosed charges.

Russian occupying authorities continued to jail Crimean Tatars, the peninsula’s predominantly Muslim indigenous ethnic group, for their civic journalism. Some have been imprisoned for years in prisons thousands of miles from their homes and families, restricted in their communication, and sometimes given food with pork in contravention of their religious beliefs.

Russia also took its transnational repression to new levels in 2024. Authorities ramped up their harassment of exiled journalists and foreign correspondents with a slew of in absentia sentences or arrest warrants – an intimidatory tactic that’s not reflected in CPJ’s census data because the journalists aren’t in jail, but serves as a chilling illustration of Moscow’s determination to control the narrative of its war in Ukraine.

Regional repression

CPJ’s annual prison census records a snapshot of those jailed on a given day – a minute past midnight on December 1. Those figures are an important barometer of the state of press freedom in a country, but lower numbers do not necessarily translate into an improved media landscape under regimes that have cracked down on independent voices.

Asia

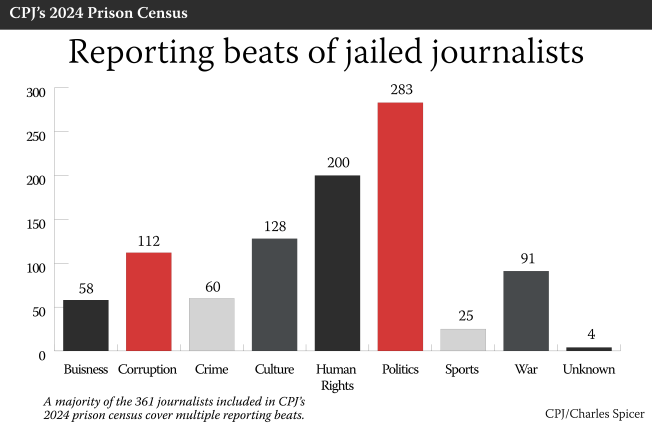

Asia remained the region with the highest number of journalists behind bars in 2024, accounting for more than 30% (111) of the global total.

Outside of China (50) and Myanmar (35), Vietnam held 16 journalists, tying with Iran and Eritrea as the seventh-worst jailer of the year. Of Vietnam’s three new prisoners in 2024, two – Nguyen Vu Binh and Nguyen Chi Tuyen – were sentenced to seven- and five-year terms respectively for propagandizing against the state. The third, Truong Huy San, is in pre-trial detention after writing critical commentary about two of the country’s top leaders – the then-ruling, now-deceased Communist Party’s long-serving chief Nguyen Phu Trong and President To Lam.

Asia remained the region with the highest number of journalists behind bars in 2024, accounting for more than 30% (111) of the global total.

Bangladesh held four journalists seen as supporters of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, ousted in August following mass protests that ended her 15-year rule. Dozens of journalists whose reporting was considered favorable toward Hasina’s government were subsequently targeted in criminal investigations.

India had three journalists in custody, two of them Kashmiris arrested in 2023 against a backdrop of increased incarceration of journalists in the Muslim-majority region after the 2019 repeal of its special autonomy status. The Taliban held two journalists in Afghanistan, and the Philippines continued to detain Frenchie Mae Cumpio on charges that could see her jailed for life.

Middle East and North Africa

A total of 108 journalists were imprisoned in the Middle East and North Africa, almost half as a result of the Israel-Gaza war. Egypt, frequently one of the top 10 jailers globally, placed as the world’s sixth-worst with 17 imprisoned journalists. Seven were detained in 2024 as the country’s economic crisis sparked a new wave of journalist arrests. At least two – cartoonist Ashraf Omar and economic commentator Abdel Khaleq Farouk – had criticized the government’s economic policies.

Iran, also routinely one of the world’s worst jailers of journalists, held 16 behind bars. Seven were taken into custody in 2024, a year that also saw newsroom raids and the sentencing of Shirin Saeedi to five years in prison for “assembly and collusion against national security” after participating in journalism workshops in South Africa and Lebanon.

A total of 108 journalists were imprisoned in the Middle East and North Africa, almost half as a result of the Israel-Gaza war.

Saudi Arabia, notorious for the 2018 murder and dismemberment of The Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in its Turkish consulate in Istanbul, had 10 journalists in its jails. Authorities continued to show little tolerance for dissent, arresting Palestinian podcaster Hatem al-Najjar following a social media campaign over decade-old tweets perceived as critical of Saudi Arabia.

Tunisia, once vaunted for its transition to democracy after its 2011 uprising launched the Arab Spring, imprisoned its highest-ever number of journalists. Four of the five in custody were detained in 2024; all face charges under Decree 54 on cybercrime, introduced in 2022 after President Kais Saied suspended parliament and introduced a constitution that gave him almost unchecked power.

CPJ recorded five journalists as jailed in Syria on its 2024 census date. Blogger Tal al-Mallohi, was freed after the December 8 ousting of Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, but the other four remain missing.

Iraq held three journalists in 2024. These included Sherwan Amin Sherwani, who was due to be released in September 2023, but remained incarcerated after Kurdish authorities sentenced him in July 2023 to another four years – reduced to two years on appeal – for allegedly falsifying documents. Qaraman Shukri also remained in prison in spite of being eligible for release under a special pardon issued by Kurdistan Region President Nechirvan Barzani in July 2024.

Bahrain also held three journalists, with one – blogger Abduljalil Alsingace – sentenced to life after pro-reform protests erupted in 2011.

In Jordan, two journalists are each serving one-year sentences after being convicted under its 2023 Cybercrime Law criminalizing online posts deemed to be fake.

Europe and Central Asia

Outside of Belarus (31) and Russia (30), Azerbaijan’s continued crackdown on independent media made it one of the leading jailers of journalists in Europe and Central Asia. Twelve of the 13 were arrested since late 2023 and come from some of the country’s last remaining independent media, including investigative outlet Abzas Media – known for its corruption investigations into senior state officials. Most of the journalists and media workers were arrested on currency smuggling charges related to alleged Western donor funding, as relations between Azerbaijan and the West declined following Azerbaijan’s military recapture of Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijan authorities also arrested and detained another six journalists and media workers with Meydan TV, Azerbaijan’s largest exiled media outlet, on currency smuggling charges after CPJ’s December 1 census date.

Turkey, with 11 imprisoned journalists – including four serving life sentences on anti-state charges – is no longer one of the world’s top media jailers. But three house arrests of reporters working for pro-Kurdish outlets in 2024 perpetuated a longstanding pattern of targeting those who report on the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which Turkey classifies as a terrorist organization. Two of those held – Mezopotamya News Agency reporter Tolga Güney and JİNNEWS reporter Melike Aydın — were indicted on charges of PKK membership. The third, Delal Akyüz, had not been charged at the time of publication.

Kyrgyzstan, once an exemplar of press freedom in post-Soviet Central Asia, continued its descent into authoritarianism as populist President Sadyr Japarov sought to bring its once-vibrant independent media under ever tighter state control.

In Tajikistan, eight journalists were imprisoned as President Emomali Rahmon continued his efforts to centralize control by silencing political opponents and independent voices. Seven journalists are serving sentences of seven to 20 years, many convicted on extremism charges after closed-door trials. Local journalists told CPJ that press freedom in Tajikistan was at its lowest point since the country’s civil war three decades earlier.

Kyrgyzstan, once an exemplar of press freedom in post-Soviet Central Asia, continued its descent into authoritarianism as populist President Sadyr Japarov sought to bring its once-vibrant independent media under ever tighter state control. Two journalists from the prominent anti-corruption investigative outlet Temirov Live, Makhabat Tajibek kyzy and Azamat Ishenbekov, are serving six and five-year sentences respectively after being convicted of calling for mass unrest. Kyrgyz authorities also shuttered Kloop, another leading outlet known for investigations into senior state officials, and enacted a Russian-style “foreign agents” law.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Eritrea remained the leading jailer in sub-Saharan Africa, with 16 journalists who were incarcerated between 2000 and 2005 still appearing on CPJ’s 2024 census. Globally, the country tied with Iran and Vietnam as the seventh-worst offenders. Those held in Eritrea include some of the longest-known cases of journalists imprisoned around the world; no charges against them have ever been disclosed. Over the years, Eritrean officials have offered vague and inconsistent explanations for the journalists’ arrests — accusing them of involvement in anti-state conspiracies in connection with foreign intelligence, skirting military service, and violating press regulations. Officials, at times, even denied that the journalists existed.

Those held in Eritrea include some of the longest-known cases of journalists imprisoned around the world; no charges against them have ever been disclosed.

In Ethiopia, five of the six journalists held by authorities are facing terrorism charges after covering the ongoing conflict in Amhara; the maximum penalty, if convicted, is death. The sixth, Yeshihasab Abera, was arrested in September 2024 amid escalating tensions in the region and reports of mass arrests of civilians, civil servants, academics, and journalists as part of a government “law enforcement operation” targeting armed groups and their alleged supporters. Officials have not provided any reason for Yeshihasab’s detention or disclosed any charges against him.

Cameroon and Rwanda each held five journalists, mostly on anti-state or false news charges.

In January 2024, Rwandan YouTuber Dieudonné Niyonsenga, who also goes by Cyuma Hassan, told a court that he was detained under “inhumane” conditions in a “hole” and was frequently beaten. Niyonsenga’s application to have his trial reviewed was rejected and he continues to serve a seven-year sentence.

Nigeria is using a cybercrimes law to prosecute its four imprisoned journalists for their reporting on alleged corruption. Despite reforms to the country’s Cybercrimes Act in February 2024, it continues to be used to summon, intimidate, and detain journalists for their work.

Burundi held one journalist, Sandra Muhoza, on CPJ’s census day. Her conviction on charges that included undermining the integrity of the national territory reflected a trend of anti-state charges against journalists in the East African nation. Floriane Irangabiye, sentenced to 10 years for the same charge in 2023, was freed in August 2024 following a presidential pardon. Similarly, in 2020 four journalists with the outlet Iwacu were sentenced to 2 ½ years for attempting to undermine state security, after reporting on clashes with rebels, and freed on a presidential pardon in December of that year.

Senegal also held one journalist: Bassène, jailed since 2018 and whose life sentence was upheld by an appeals court in 2024. Bassène did not appear in CPJ’s previous prison censuses because research at that time could not confirm that his detention was connected to his work.

Latin America and the Caribbean

Six journalists were held in Latin America and the Caribbean on December 1: three in Venezuela, and one each in Nicaragua, Cuba, and Guatemala. All except Guatemala’s Zamora, who was jailed in 2022, were detained in 2024.

This comparatively low number, however, should not be seen as a positive indicator of media freedom in a region where political instability and authoritarian rule fuel crackdowns on the press. Haitian authorities, for example, don’t hold any journalists in jail, but at least nine have been killed there since 2022 – mostly by criminal gangs – and CPJ’s 2024 Global Impunity Index found Haiti to be the top country where murderers of journalists were most likely to go unpunished.

Venezuela’s government responded to nationwide protests after President Nicolás Maduro’s disputed election victory in July 2024 by intensifying its repression of journalists and fostering a climate of fear and self-censorship by framing critical coverage as terrorism or a threat to national security.

In Nicaragua, Elsbeth D’Anda was taken into custody after reporting on rising food prices on his television show on pro-government Channel 23 – highlighting the government’s intolerance of even mild scrutiny.

In Guatemala, the judicial persecution of Zamora reflects how legal systems are used to silence journalists and the ongoing erosion of press freedom in the country.

Freedom, achieved

While 2024 was a heartbreaking, and, in several countries, a record-breaking year for journalists imprisoned around the world, some hope shone through. Around 90 journalists were freed ahead of CPJ’s December 1 annual prison census and, although some still faced exile or post-prison harassment, they managed to be reunited with friends and family. Here are images of some of those journalists who finally were released from jail.

Recommendations

The Committee to Protect Journalists makes the following recommendations to prevent arbitrary and retaliatory incarceration of journalists:

1. End the practice of detention without charge

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights–to which the majority of the world’s leading jailers are signatories–provides that no one should be subject to arbitrary arrest or detention. Detention is considered arbitrary when, among other things, a victim is not provided with a legal reason for their arrest nor brought before a judge within a reasonable time.

Governments holding journalists without charge must:

– Cease the practice of arbitrary detention and immediately release arbitrarily detained journalists.

– Ensure authorities do not beat, torture, or otherwise abuse detained journalists.

– Investigate all allegations of abuse and mistreatment, and ensure those responsible officials are brought to justice.

Rights-respecting governments should:

– Prioritize ensuring the immediate release of all arbitrarily detained journalists during diplomatic engagements with governments listed as leading jailing of journalists.

– Impose targeted sanctions on officials and others directly engaged or complicit in the deliberate misuse of law to undermine press freedom rights.

– Make compliance with international human rights norms and practices a prerequisite for bi-lateral and multilateral trade and security agreements, particularly where this relates to arbitrary detention, cruel and degrading treatment, and post-prison restrictions.

– Ensure that multilateral platforms and/or organizations with a human rights or press freedom mandate prioritize the release of unjustly held journalists. This includes:

1- Members of the Media Freedom Coalition, a group of more than 50 member states that seek to promote and protect a free press, prioritizing the release of unjustly held journalists by engaging in robust and sustained diplomatic efforts and public pressure where appropriate or needed;

2- National human rights institutions and the U.N. Human Rights Council spotlighting cases of wrongfully imprisoned journalists, and their wider repercussions for shrinking civic space, freedom of expression, and meaningful exercise of fundamental rights.

3- Ensuring that the Universal Periodic Review process consistently and rigorously focuses on press freedoms, including detailing any arbitrarily detained or imprisoned journalists, and that member countries vigorously seek to implement recommendations for freedom and reform.

CPJ also encourages other actors in the international community, beyond those mandated to address press freedom or free expression, to consider the significant impact the crackdown on journalists has on economic development, global security, electoral integrity, and other critical issues of international concern, and to incorporate demands for press freedom and the release of detained journalists in their work. For example, development banks could require government clients to release jailed journalists as a condition of loan or publicly condemn reprisals against journalists, and the wider ecosystem of UN special envoys and special rapporteurs should consider how press freedom relates to their own mandates.

2. Repeal and reform cybercrime laws that target journalists

Cybercrime laws and similar legislation governing online content over the past decade increasingly use the guise of ‘fighting cybercrime’ to criminalize and jail journalists in Bangladesh, Jordan, Nicaragua, Nigeria and Pakistan, among others.

The United Nations Convention against Cybercrime was officially adopted in December 2024 and will enter into force in 90 days after being ratified or accepted by 40 member states. As CPJ and other groups – including digital security experts, industry, and the United Nation’s own human rights office – have argued, the convention, first proposed by Russia, has broad provisions that risk subjecting journalists and other vulnerable groups to unwarranted investigations, prosecution, surveillance, and transnational repression for exercising fundamental human rights while using digital technology.

Governments with existing cybercrime laws must:

– Review existing national legislation governing online content for provisions that could be used to prevent or punish journalism.

– Repeal existing laws that create a risk, or reform them to ensure they contain appropriate guardrails that prevent them from being wielded to prevent or punish reporting.

Rights-respecting governments should:

– Monitor new proposed legislation to ensure there are no provisions that could be used to prevent or punish journalism.

– Refrain from ratifying the U.N. Convention against Cybercrime. Any countries proceeding with adoption must implement it with rigorous safeguards to minimize the convention’s most harmful elements.

3. End the misuse of anti-state and financial crime laws to punish journalists

Legal experts have found that the abuse of laws and manipulation of legal systems to persecute or retaliate against individuals is a form of judicial harassment. Judicial authorities must be enabled to recognize these efforts for what they are and exercise the appropriate judgement to mitigate harm.

– Judicial authorities, supreme courts, national law commissions and/or other appropriate bodies should develop guidelines for handling cases involving routinely abused legislation and curbing the misuse of laws to wrongfully deprive journalists of their liberty. Similarly, courts should ensure that journalists who have formally served their sentences are not kept in prison beyond that period.

– National legislative or other appropriate bodies should review press freedom indicators like CPJ’s records of imprisoned journalists and work with local, regional and/or international civil society groups to reform legislation routinely abused to retaliate against journalists for their reporting.

4. End targeting of journalists’ lawyers

In recent years, CPJ has identified lawyers of journalists facing retaliation in Iran, China, Belarus, Turkey, and Egypt, the countries that are among the world’s worst jailers of journalists. This trend continued in 2024, as evident in the case of Jimmy Lai, whose family and international counsel are subject to retaliatory tactics by China, the world’s leading jailer of journalists.

– Professional legal groups and bar associations should support, protect, and advocate on behalf of lawyers defending journalists and news outlets targeted and intimidated for their work.

– Rights-respecting governments should advocate for persecuted lawyers in bilateral and multilateral forums, and evaluate opportunities for supporting them in exile.

5. Ensure leading jailers change their practices and are held to account

China

CPJ calls on China to end its years-long repression of journalists, including its targeted persecution of Uyghur journalists. China should begin to address its abysmal record on journalist jailings by ending Jimmy Lai’s sham trial in Hong Kong and releasing him without delay. The United Kingdom, which is a founding member of the Media Freedom Coalition, must make the case of Lai, a British national, a priority at the highest levels of government.

Israel

Israel must respect the repeated decisions by the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention that its practice of administrative detention in the West Bank violates international human rights law. In particular, Israel must comply with the recent determination – in a case filed by CPJ – that its detention of three Palestinian journalists was discriminatory, arbitrary, and in violation of international law. Israel should heed the working group’s call to investigate the detentions – as well as that of other journalists still held without charge under administrative detention – hold those responsible for these rights violations to account, and provide the aggrieved journalists with compensation or reparations in accordance with international law.

CPJ urges Israel’s Military Advocate General in particular, to include the treatment of journalists in the ongoing probes into military actions during the Israel-Gaza war and pay special attention to the cases already reviewed by the U.N. legal experts.

Myanmar

CPJ urges the military regime to work with others to implement U.N. Security Council resolution 2669 (adopted in 2022), which calls for the release of arbitrarily detained prisoners. We urge the U.N. special envoy on Myanmar to meet with press freedom groups and consult journalists in exile ahead of future country visits as she pursues continued constructive engagement with the regime.

In seeking to implement ASEAN’s Five-Point-Consensus, the chair and special envoy should consult with exiled journalists and press freedom groups, and advocate for a restoration of press freedom. It is vital that ASEAN assume leadership in securing the prompt release of imprisoned journalists as an initial step in the yet-to-be implemented plan.

Belarus and Russia

As hundreds of journalists have fled Belarus and Russia, both countries have significantly increased filing charges, arrest warrants and sentencing journalists in absentia, making them vulnerable to detention on bogus or fabricated charges, even in exile.

Countries that have provided safe refuge to Belarusian and Russian journalists, such as Germany, Sweden, the United States, and the United Kingdom, should protect them from persecution, surveillance, and other harms that may stem from Russia’s arbitrary legal actions. Russia must also refrain from the retaliatory imprisonment of Crimean Tatar journalists as part of its years-long occupation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula.

Local authorities and legislators in host countries should further consider taking necessary measures to ensure that their own legal systems and diplomatic relations are not abused for the purposes of retaliating against journalists or using them as political pawns.

(Editor’s note: This report has been updated to correct the number of journalists arrested in Azerbaijan since late 2023.)

Census methodology

CPJ’s annual prison census is a snapshot of journalists jailed globally for their work as of 12.01 a.m. on December 1. The census includes only those journalists CPJ has confirmed to have been imprisoned in relation to their reporting or coverage by their outlet; it does not include those classified as “missing” or “abducted” if they have disappeared or are held captive by non-state actors.

CPJ defines journalists as people who cover the news or comment on public affairs in any media, including print, photographs, radio, television, and online. It does not include the many journalists imprisoned and released throughout the year; accounts of those cases can be found at http://cpj-preprod.go-vip.net. Journalists remain on CPJ’s list until the organization determines with reasonable certainty that they have been released or have died in custody.

Arlene Getz is editorial director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. Now based in New York, she has worked in Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East as a foreign correspondent, editor, and editorial executive for Reuters, CNN, and Newsweek. Follow her on LinkedIn.

Editor’s note: This report has been updated to make minor changes to data in charts pertaining to gender, job status, reporting beats, sentences, and charges.