Prosecutors say every lead has been pursued, every witness questioned in the slayings of editors Valery Ivanov and Aleksei Sidorov. But no one has ever been convicted, and no one can explain what investigators did with the most compelling lead. A CPJ special report by Nina Ognianova

Published October 27, 2011

TOGLIATTI, Russia

On a sunny June afternoon, Stella Ivanova takes a visitor to the working-class neighborhood where her brother, Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye editor Valery Ivanov, had lived nearly a decade earlier. As she reaches Gaya Boulevard, she pulls up to a gloomy apartment block and parks in front of entrance No. 3.

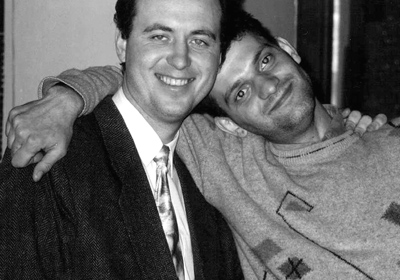

It was there, on the evening of April 29, 2002, that a half-dozen young people had gathered to enjoy a warm spring night and drink some beer. Valery Ivanov had parked his Niva sedan at the curb, no more than a meter away from the wooden bench where they had clustered. Around 11 p.m., Ivanov left his apartment and got into his car to run an errand. A man, apparently waiting nearby, strode up to the 32-year-old editor, shooting him eight times at point-blank range with a Makarov pistol outfitted with a silencer. The killer was not wearing a mask, and he left the scene on foot, cavalierly tossing the gun in a nearby lot.

More on this issue

• CPJ’s recommendations

• Global Campaign

Against Impunity

In print

• Download the pdf

In other languages

• Русский

“The young woman who came looking for me was hysterical,” Ivanov’s widow, Yelena, says later. “She just kept saying, ‘He killed him, he killed him.’ She didn’t make any sense.” Although it made no sense at all, it was true: Ivanov was pronounced dead at the scene.

Investigators had much to work with: the young eyewitnesses who saw the crime unfold, the murder weapon, and the statements from family and colleagues who could point to a number of people—businessmen, criminals, politicians, and police—angered by the paper’s muckraking coverage of crime and corruption in Russia’s gritty auto-making capital. Yet authorities never arrested a single suspect.

Eighteen months after the murder, Ivanov’s close friend and successor as Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye editor, Aleksei Sidorov, was stabbed to death in front of his own apartment building. That case, too, is unsolved. Despite the evident connections between both Togliatti murders, authorities never joined them under one inquiry. Investigators did little to pursue a common, obvious, and compelling lead—that both editors were working on a story about alleged police malfeasance when they were killed. Back in 2003, in the Sidorov case, prosecutors brought flimsy charges against an innocent man; today, in the Ivanov case, investigators say they are seeking a suspect whom many believe to be dead. No mastermind has been identified in either case.

The two unsolved cases offer a window into Russian law enforcement’s poor overall record in solving the murders of journalists. In 19 work-related journalist murders since 2000, authorities have won convictions in only two cases, the product of a criminal justice system beset by corruption, lack of accountability, and conflicts of interest. Authorities have made some recent progress in addressing this record of impunity—one of the world’s worst—by winning convictions in the 2009 slaying of Anastasiya Baburova and making arrests in the 2006 murder of Anna Politkovskaya. But it is provincial cases like these in Togliatti, lower in profile and subjected to powerful local political influence, that test national leaders’ commitment to upholding the rule of law.

Hopes stirred, then lost

A centralized federal system, overseen in Moscow with regional offices throughout the country, investigates and prosecutes the most serious crimes in Russia, including murders. Authorities say they have taken steps to promote independence and accountability in the system. In 2007, the administration of President Vladimir Putin separated investigative functions from the prosecutorial system, creating a network of investigative committees to probe crimes. The prosecutor general’s system decides, as it did before, what charges to bring and tries the cases in court.

In 2010, after meeting with a CPJ delegation alarmed by the country’s decade-long rash of unsolved journalist murders, the federal Investigative Committee announced that it would reopen several dormant cases. Federal officials also moved the Togliatti cases out of the local jurisdiction and put them in the hands of the regional Investigative Committee in Samara. The moves were applauded by the journalists’ colleagues and relatives who said the cases could never be properly investigated by the same Togliatti authorities whom Ivanov and Sidorov had regularly criticized in their newspaper.

Hopes began to stir. After nine years, would grieving families finally see justice? CPJ traveled to Samara and Togliatti, meeting investigators as well as the victims’ colleagues and members of their families. Despite heightened expectations, though, the renewed investigations have yielded little tangible results.

Vitaly Gorstkin, head of the Samara Investigative Committee, told CPJ that investigators had identified a suspected gunman in the Ivanov case, a reputed member of the organized crime group Shamilyovskaya wanted in several other murders. He said the suspect, Sergey Afrikyan, 38, was believed to have fled Russia and was being sought internationally. No other suspects are in custody or being sought in the Ivanov murder, although Gorstkin acknowledged that investigators have not identified a mastermind in the killing. He told CPJ that the investigators consider Ivanov’s journalism and business activities as likely motives.

Ivanov’s relatives are skeptical about the current investigation. Russian news reports, after all, say that Afrikyan, a local entrepreneur who allegedly moonlighted as a hired assassin, is believed to have been murdered himself after the attempted killing of a Samara judge went awry. “I think they just found a dead man and decided to blame several crimes on him at once,” Stella Ivanova, the journalist’s sister, told CPJ.

“This theory makes it easy for the investigation to close the books on my husband’s murder,” said Yelena Ivanova, the editor’s widow. “I do not believe there is a serious investigation in place. This is how it is: They make a first step, some symbolic gesture, but then there is no follow-up.” She said an official with the Samara Investigative Committee met with her in October 2010 to assure her that “this time the investigation would be different” and that her husband’s killers would be brought to justice. She said she has not heard from the committee since.

As it turns out, active work on the case was suspended in April after investigators determined there were no further leads or suspects to pursue, Gorstkin told CPJ. “But police still check for new clues,” he said. “The intensity of our operational work is beyond question.” He said authorities had questioned every relevant witness, including people presented in a negative light in Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye articles, and exhausted every potential lead.

Except, it seems, for one lead that might link the two Togliatti murders.

In April 2002, Ivanov was researching allegations that local law enforcement officials had pocketed the assets of reputed gangster Dmitry Ruzlyaev, who was slain in 1998, Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye journalists told CPJ. Ivanov never finished the article, but, as the author Terry Gould first reported and CPJ recounted in its 2009 investigation, Anatomy of Injustice, Sidorov pushed ahead with the research, seeking out financial documents he believed would connect law enforcement officials to Ruzlyaev’s missing assets.

On the evening of October 9, 2003, Sidorov told a colleague that he had received an important batch of records and was prepared to finish the article. With those documents in his possession, he went home to meet guests. As he arrived at his apartment building, an unidentified assailant stabbed him multiple times.

Gorstkin said the Ruzlyaev matter was “part of the investigation,” but would not provide any details as to what investigators did with the lead. Overall, he said, detectives looked at several potential suspects in the Sidorov case but found no evidence to charge them, leaving him “pessimistic” about the prospects of solving the murder. Four months after the Sidorov case was reopened, it was suspended again, on January 21, 2011, Gorstkin said. The suspension was not publicly announced and received no press coverage.

Despite appeals from colleagues and relatives, Gorstkin said the Ivanov and Sidorov cases would not be joined into a single investigation because “they are completely different.”

A lead disregarded

Sidorov’s father, Vladimir, keeps a thick archive of documents, correspondences with authorities, and press coverage he accumulated in the years after his son’s murder. Using a provision of Russian law, he and his lawyer also obtained the prosecution’s file in the case. Among the materials are statements that Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye reporters gave to authorities about the sensitive stories Sidorov had been pursuing before his murder—potential clues that the journalist’s father believes investigators dismissed without proper follow-up. The stories include the alleged malfeasance in the Ruzlyaev case. In one statement, a Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye reporter told detectives that Aleksei Sidorov claimed to have obtained records proving the misappropriation of Ruzlyaev’s assets. “Millions, big money, big property,” Vladimir Sidorov said. “But authorities did nothing to investigate this.”

Nikolai Shpakov, the district prosecutor who helped oversee the original Sidorov murder probe, told CPJ he does not remember that lead. “I cannot recall any specifics,” he said when asked whether the editors’ work on the Ruzlyaev matter had been considered a possible motive. “But we investigated every possible lead.”

That original investigation led to the deeply flawed prosecution of Yevgeny Maininger, a local factory worker. Authorities claimed a drunken Maininger stumbled upon Sidorov, appealed for some vodka, and then murdered the editor in a rage when he was rebuffed. After three days of interrogation, authorities extracted a confession from Maininger. But the defendant soon retracted his statement and said it was coerced; eyewitnesses described a taller assailant than the defendant; and Maininger’s co-workers said they were pressured to falsely implicate him in the crime. Sidorov’s colleagues and relatives hailed Maininger’s acquittal in October 2004, saying the case against him had been fabricated.

Today, Shpakov blames the editor’s father and colleagues for being unhelpful in the investigation. “All were questioned,” he said of Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye journalists. “But, as I recall, they didn’t give us any concrete data that we could further investigate. … The father did not give us any information whatsoever. The only thing we got from him was a categorical rejection that his son could have been killed for any other reason than his professional activity. Any other argument he did not understand and would not accept. He never gave us any facts that we could check out—not during the investigation, not during the trial, not today.

“The work of the investigator is to do everything possible. And I have to say that in this case, the investigators did everything possible,” said Shpakov, who now heads the Investigative Committee in Togliatti.

And that has left Vladimir Sidorov without trust in Russia’s criminal justice system. In Togliatti, he notes, the Investigative Committee is staffed by some of the same people responsible for the original, faulty probe. After the Maininger case went to trial, the Sidorovs and their lawyer reviewed the prosecution’s file and found what they claimed were numerous instances of investigative failures. For years, Vladimir Sidorov tried to file a legal complaint against authorities, he told CPJ. “I wrote letters everywhere, including to government ministers and parliamentary deputies, to no result. I found out that, in Russia, it is impossible for an ordinary man to sue prosecutors and investigators. At one stage, for instance, a district court accepted my claim. But the next court up overruled that decision. In another instance, a parliamentary deputy promised that all appropriate measures would be taken, but nothing happened. Instead, some of the officials I wanted to sue got promoted. … And then I understood that I cannot overcome the system by myself,” he said.

Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye, the iconic muckraking newspaper that tackled local corruption, organized crime, and government wrongdoing, is a shadow of what it once was. Since Sidorov’s murder in 2003, the newspaper has changed editors six times; it has also changed owners and its editorial positions. The staff is almost entirely changed, former colleagues of the two slain editors told CPJ. Ivanov and Sidorov’s legacy is in jeopardy—in February 2008, special agents from the Togliatti police department raided Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye’s newsroom and confiscated all of its 20 computers under the pretext of looking for unlicensed Microsoft software.

Newspaper staff members believe the seizure was in retaliation for its coverage, and Microsoft later distanced itself from such raids, saying, “We unequivocally abhor any attempt to leverage intellectual property rights to stifle political advocacy.” The confiscated hard drives contained the electronic archive of Tolyattinskoye Obozreniye—all of the newspaper’s investigations published under Ivanov and Sidorov’s editorship since the founding of the newspaper in 1996. The computers were never returned.

The Togliatti murder investigations illustrate the systemic problems that afflict the other 15 unsolved journalist murders committed in Russia since 2000. Despite the incremental progress Russian authorities have made in combating impunity, most investigations continue to fail due to a lack of political will. In the cases of Valery Ivanov and Aleksei Sidorov, new promises of commitment have given way to old habits of neglect. Vladimir Sidorov put it this way: “The system is a corporate organism. An individual cannot do anything on their own.” Russian authorities must work hard to prove Sidorov’s skepticism wrong. And they can do that only one way—by finding, prosecuting, and convicting the killers of Valery Ivanov and Aleksei Sidorov. The real ones.

Nina Ognianova, CPJ’s Europe and Central Asia program coordinator, conducted a three-month fact-finding mission to Russia in 2011 as part of CPJ’s Global Campaign Against Impunity at the invitation of the Russian Union of Journalists. CPJ’s Global Campaign Against Impunity is underwritten by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

CPJ’s recommendations

To the Russian federal Investigative Committee:

• Reopen investigations into the murders of Valery Ivanov and Aleksei Sidorov.

• Join the two murder cases into one probe.

• Thoroughly investigate whether the editors were killed in relation to their reporting on alleged police misappropriation of Dmitry Ruzlyaev’s assets. Both editors were working on a story about the allegations at the time of their murders. Publicly report the investigative results.

• Exercise regular and thorough oversight of the work of the regional Samara branch of the Investigative Committee into the Togliatti murders. Ensure that independent investigators work on the cases and that their work is not obstructed.

• Ensure that relatives of the murdered editors are regularly informed of any developments in the investigations.

• Grant access to the case files to both the Ivanov and the Sidorov families and their legal representatives.