Updated June 25, 2020

The United States is scheduled to hold presidential and congressional elections on November 3, 2020. Journalists covering elections and political rallies in the U.S. in recent years have been subjected to online and verbal harassment and even physical assault, CPJ has found.

With ongoing protests against police brutality and racial injustice taking place across the U.S., in addition to the resumption of President Donald Trump’s political rallies after a temporary pause due to the coronavirus, media workers should be aware of the risks of exposure to COVID-19 infection when covering any rally and/or protest.

CPJ Emergencies has updated its safety kit for journalists covering the 2020 election, including information for editors, reporters, and photojournalists on how to prepare for such assignments and how to mitigate COVID-19, digital, physical, and psychological risk.

Journalists with further questions can contact CPJ via electionsafety@cpj.org.

Contents:

- Editor’s Safety Checklist

- Physical Safety: Covering rallies and protests

- Digital Safety: Online harassment and trolling

- Digital Safety: Identifying bots

- Digital Safety: Protecting your devices

- Digital Safety: Dealing with Misinformation

- Resources

Editor’s Safety Checklist:

During the run up to the election, editors and newsrooms may assign journalists and other media workers to cover political rallies and related protests at short notice.

This checklist includes key questions and steps to consider, to help reduce the risks for staff.

Staff Checklist

- Do team members fall into a higher risk category of vulnerability to COVID-19; reside with anyone from a higher risk category; or have any vulnerable dependents living elsewhere, such as elderly relatives?

- Do team members have the appropriate level of experience for the particular assignment, noting the potential for verbal and physical hostility toward the media?

- Does the ethnicity of any team member increase the chances of hostility toward them, either at the rally or any related protests?

- Do any team members suffer from stress, anxiety, or depression? Have you considered the possibility of long-term trauma-related stress? For further details, see CPJ’s safety note on psychological safety

- Will any individuals be working alone? The risks for solo assignments can be considerably greater. Consideration should be given to how the individual will raise the alarm or seek assistance if necessary. For further details, see CPJ’s safety note on solo working

- Does the role or profile of any journalist on assignment put them at more risk? (E.g. photojournalists who work closer to the action or individuals who may attract unwanted attention due to their identity, political views, or outlet.) If the answer is yes, provide details:

Equipment Checklist

- Do team members have access to the necessary PPE (personal protective equipment), such as N95 / FFP3 face masks, disposable gloves, and hand sanitizer? (The CDC recommends the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers with greater than 60% ethanol or 70% isopropanol)

- If protests are likely, is special personal protective equipment such as body armor, ballistic goggles, respirators, or a medical kit required? If so, do media workers have access to such equipment and do they know how to use it properly?

- Is a range of recording equipment available to help maintain physical distancing, such as fishpole microphones and long distance lenses?

- Have you discussed the importance of a strict and regular EQUIPMENT cleaning regime, for individuals as well as the equipment they are using?

- Have you discussed how individuals will travel to and from the assignment? Public transport should be avoided if possible, especially during peak travel periods

Administration Checklist

- Have you recorded and saved securely the emergency contacts of all staff being sent on assignment?

- Do all team members have the correct and appropriate accreditation, press passes, or a letter indicating that they work for your organization? Check with local authorities on the appropriate accreditation

- Do all team members have the appropriate legal contacts/information in the event that they are arrested or detained?

- Is the team correctly insured, and have you put in place appropriate medical cover?

- Have you discussed what plans are in place to assist and support individuals should they fall ill while on assignment, taking into account the possibility of self-isolation and/or being grounded in a quarantine/lockdown zone for a period of time?

- Detail here how often and by what means you will communicate and check-in with the team. Also provide details of how they will remove themselves from an emergency situation if necessary:

- Have you identified all of the local medical facilities in the area in case of injury? Please record the details below:

- Detail potential risks and measures put in place to make staff safer:

(If necessary complete on another piece of paper and attach.)

For more information about risk assessment and planning, see the CPJ Resource Center.

Physical Safety: Covering rallies and protests

Maintaining physical/social distancing at any political rally or protest will be incredibly challenging. Members of the public may not wear face coverings/face masks at all, and media workers could be confined to a particular area in close proximity to other journalists. Such confinement could potentially expose them to virus droplets, as well as to verbal or physical attack from hostile members of the public—who could deliberately cough or sneeze over them.

Journalists have been physically assaulted and verbally abused at political events, rallies, and protests in the U.S., with an unprecedented number of reported incidents during protests against police brutality and racial injustice that began in late May 2020, as documented by the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, of which CPJ is a founding partner.

Journalists should be cognizant of differing legislation, gun control regulations, and police tactics in each U.S. state. Coverage of protests in the U.S. in recent years has shown police using rubber bullets, bean bag rounds, tear gas, and water cannon to quell protesters. If emotions run high at a rally or protest, the risk of violence increases and can be life-changing and/or fatal. A bystander, Heather Heyer, was killed in a vehicle ramming after the August 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, while journalist Linda Tirado was left blind in one eye after being struck by a rubber bullet while covering a protest against police brutality and racial injustice in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

To minimize the risk:

Political events and rallies

Be aware that people shouting or chanting can result in the spread of virus droplets, therefore increasing media workers’ level of exposure to COVID-19 infection.

- Ensure that you have the correct accreditation or press identification. For freelancers, a letter from the commissioning employer is helpful. Have it on display only if safe to do so. Do not use a lanyard, but clip it to a belt

- Research if any form of physical distancing will be in place and/or enforced at the rally venue.

- Ensure you wash your hands regularly, properly, and thoroughly throughout the assignment, for at least 20 seconds at a time using hot water and soap. Ensure hands are dried in the appropriate way. Use hand sanitizer regularly if you cannot wash your hands, but do not make this a substitute for a regular hand washing routine

- On arrival, identify all potential exit routes and officials who may be in a position to help if needed. Discuss your plans with other members of the press

- Identify where you will be located in the venue. Be aware of potential risks from any “press pen” location, such as if the media are positioned centrally

- Constantly monitor for individuals in the crowd who may become aggressive or cause trouble, and try to avoid them as much as possible. Be aware of individuals getting close to you, who could cough or sneeze over you — either accidentally or deliberately

- Gauge the mood of the audience. Before the event starts it may be possible to have friendly engagements with members of the crowd to create a rapport (from a safe distance of at least 6 feet [2 meters]). Be cautious if people appear to have been drinking alcohol or are emotional

- Wear clothing without media company branding, and remove media logos from equipment and vehicles if necessary. Avoid wearing any clothing with a political slogan or message. Wear appropriate footwear that allows you to move fast if necessary. All clothing and shoes should be removed before re-entering your home and washed/cleaned with hot water and detergent

- If the crowd or speakers are likely to be or start to become hostile to the media, mentally prepare yourself for verbal abuse. In such circumstances, just do your job and report. Do not react to the abuse or engage with the crowd. Remember, you are a professional even if others are not

- If a crowd becomes hostile to the media it may help to deliberately avoid eye contact and stop taking pictures/filming. You will need to balance the risk versus reward, but if a crowd is becoming inflamed, engagement of any sort can be perceived as a challenge

- If coughing, sneezing, spitting, or small missiles from the crowd are a possibility, consider wearing a hooded, waterproof, and discrete bump cap and keep your N95 / FFP3 standard face mask on

- Do not be alarmed if you see increased levels of security. Some news organizations have started to bring security guards to political events

- If an event has been hostile, do not hang around afterwards to interview people. Vox pops and interviews after such an event could increase the risk for hostility or other problems

- If the objective is to report from outside, working with a colleague is sensible. Report from a secure and visible location with clear exits and familiarize yourself with the route to your transportation. If an assault is a realistic prospect, consider the need for security and minimize your time on the ground to what is absolutely necessary

- Have an escape strategy in case circumstances become hostile. You may need to plan this on arrival, but do so before beginning the assignment. Park your vehicle in a secure location that’s facing the direction of escape — or ensure you have a guaranteed mode of transportation

- Plan an emergency rendezvous point if you are working with others and are unable to get to your means of transportation. Know the closest point of medical assistance

- If the task was difficult, do not bottle up your emotions. Tell your superiors and colleagues. It is important that they are prepared and that everyone learns from each other

- All recording equipment should be thoroughly cleaned

Protests

Physical/social distancing guidelines are unlikely to be adhered to during a protest, with no certainty that individuals will wear a face covering/face mask. Be aware that people shouting or chanting can spread virus droplets, therefore increasing media workers’ level of exposure to COVID-19 infection.

- Media workers should have access to and wear N95 / FFP3 standard face masks, disposable gloves, and a supply of alcohol-based hand sanitizer

- Based on the levels of violence and tactics used by both police and some members of the public at protests against police brutality and racial injustice, ballistic glasses, helmets, and stab vests should be considered. If there is a threat of live ammunition being used, then body armor should also be considered

- Know your legal rights in the state you are in before reporting on any protest or crowd situation

- Plan the assignment and ensure that you have a full battery on your cell phone. Know the area you are going to. Work out in advance what you would do in an emergency. Take a medical kit if you know how to use it

- Always try to work with a colleague and have a regular check-in procedure with your base. Note that large crowds create potential risks of sexual assault. Working after dark is considerably more risky and should be avoided. For more information please see CPJ’s advice for journalists reporting alone

- Wear clothing and footwear that allows you to move swiftly. Tie long hair up, and avoid loose clothing and lanyards that can be grabbed, as well as any flammable material, such as nylon

- Always consider your position and maintain constant situational awareness. If you can, find an elevated vantage point that may offer greater safety

- Have an escape strategy in case circumstances become hostile. You should plan this in advance by examining maps of the location, and go through the plan again on arrival, which may need to be modified based upon local circumstances (such as road closures)

- Always park your vehicle in a secure location facing the direction of escape, or ensure you have an alternative guaranteed mode of transport

- Plan an emergency rendezvous point if you are working with others and unable to get to your means of transportation. Know the closest point of medical assistance

- Limit the number of valuables you take with you and avoid wearing expensive jewelry and/or watches. Do not leave any equipment in vehicles, which could be broken into. After dark, the criminal risk increases

- If working in a crowd, plan a strategy. It is sensible to keep to the outside of the crowd and not get sucked into the middle, where it is hard to escape. Be aware of the risk for potential attacks, such as a vehicle ramming, as well as the dangers from ‘kettling.’ Being in such close proximity to others will potentially increase your level of exposure to COVID-19 infection

- Photojournalists generally have to be in the thick of the action so are at greater risk. Photographers in particular should have someone watching their back and should remember to look up from their viewfinder every few seconds. Do not wear the camera strap around your neck to avoid the risk of strangulation. Photojournalists often do not have the luxury of being able to work at a distance, so it is important to minimize the time spent in the crowd. Get your shots and get out

- All media workers should be conscious of not outstaying their welcome in a crowd, which can turn hostile quickly

- Police in some states use crowd control tactics including rubber bullets, bean bag rounds, tear gas (see below), and water cannon. In open carry states, members of the crowd could be armed

- At major protests, be conscious that the police may be from other localities. They may not know the geography of the area or be as familiar with local legislation. In case of unrest, lack of communication between different police forces could result in breakdowns of command and control

- Pay close attention to the demeanor of the police. If they are relaxed, then it is a good time to carry on with your reporting. If they are in armor, with shields or in lines, this is a likely indication they are preparing for unrest. Consider your exit plan at this stage and pull back to safety if trouble breaks out

- Several states use mobile bicycle police units. These units have previously used the bikes as barriers or to corral protesters

- If firearms are visible, move to hard cover and do not dwell in natural exits in case of a stampede

Dealing with tear gas:

The use of tear gas can result in sneezing, coughing, spitting, and the production of mucus that obstructs breathing. In some cases, individuals may vomit, and breathing may become labored. Such symptoms could potentially increase media workers’ level of exposure to COVID-19 infection via airborne virus droplets. In addition, evidence suggests that tear gas can actually increase an individual’s susceptibility to pathogens such as the novel coronavirus, as highlighted by NPR.

- Media workers who suffer from respiratory issues such as asthma are listed in the vulnerable category. Because of this, and the possibility of tear gas being used at protests, they should avoid covering protests if possible

- Wear personal protective equipment that includes a gas mask/full face respirator, eye protection and a helmet — all of which should help protect you. Media workers without the appropriate PPE should always consider their position, and retreat to a safe location if tear gas is deployed

- Contact lenses are not advisable. If large amounts of tear gas are being used, there is the possibility of high concentrations of gas sitting in areas with no movement of air

- Wear clothes that cover your arms and legs, and avoid wearing any make-up and oil-based creams

- Take note of any potential landmarks (i.e. posts, curbs) that can be used to help you navigate out of the area if you are struggling to see

- If you are exposed to tear gas, try to find higher ground and stand in fresh air to allow the breeze to carry the gas away. Do not rub your eyes or face as this may worsen the situation. Once possible, shower in cold water to wash the gas from skin, but do not bathe. Clothing may need to be washed several times to remove the crystals completely, or even discarded

Journalists have previously been assaulted at political rallies. When dealing with aggression:

- Gauge the mood of protesters toward journalists before entering any crowd, and watch for potential assailants

- If confronted, read body language to identify an aggressor and use your own body language to pacify a situation

- Maintain eye contact if someone is directly attacking you, use open hand gestures and keep talking with a calming manner

- Keep an extended arm’s length from the threat. Back up and break away firmly without aggression if held. If cornered and in danger, shout

- If aggression increases, keep a hand free to protect your head and move with short deliberate steps to avoid falling. If in a team, stick together and link arms

- While there are times when documenting aggression is crucial journalistic work, be aware of the situation and your own safety. Taking pictures of aggressive individuals can escalate a situation

- If you are accosted, hand over what the assailant wants. Equipment it is not worth your life

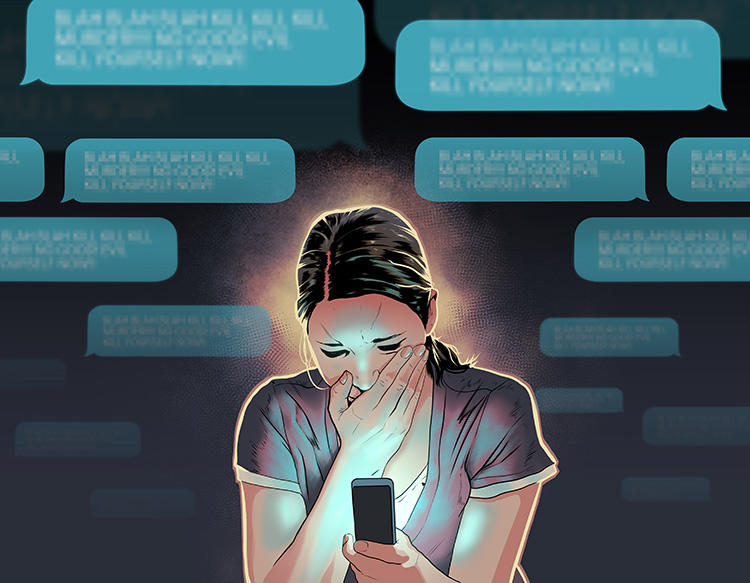

Digital Safety: Online Harassment and Trolling

Journalists who may face an increased level of online harassment during election time should take steps to protect themselves and their accounts. Journalists should monitor their social media accounts regularly for increased levels of trolling or for signs that an online attack may become a physical threat. CPJ has documented how journalists have been trolled online and doxed by groups. CPJ is aware of online attackers and trolls harassing family members through the relatives’ social media accounts.

Protecting yourself

To minimize the risk:

- Use a password manager to create long, unique passwords for all your accounts. Passwords should be between 20 to 30 characters

- Turn on two-factor authentication (2FA) for your accounts

- Review your privacy settings for each account and make sure any personal data, such as phone numbers and date of birth, is removed. Review the privacy settings of your social media accounts and limit what personal information is available to the public

- Look through your accounts and remove any photos or images that could be manipulated and used as a way to discredit you. This is a common technique used by trolls

- Have personal information deleted from data broker sites by using services such as DeleteMe. You will need to set up a continuous subscription if you want your data to continue to be removed. Be aware that these services remove data from the most common data broker sites and it is likely that your personal information will continue to exist on the internet in some form. If you are the target of an online attack, you should consider adding family members to the subscription service

- If you have been doxed or feel that you are at risk of identity theft, contact your bank and your utilities companies and alert them to possible fraudulent activity on your accounts

- Sign up for credit monitoring services that alert you to potential fraudulent activity

- Turn off geo-location for posts. If you’re going to post photos of your exact location, consider waiting until after you have left the place

- Contact Google to blur or remove your house from Google maps so it is not easy to identify

- Consider getting your accounts verified by social media companies. This is a blue tick alongside your name confirming that the account is yours. This will help others to identify your account from fake accounts set up in your name

- Monitor your accounts for signs of increased trolling activity or for indications that a digital threat could become a physical threat. Be aware that certain stories are likely to attract higher levels of harassment

- Speak with your media outlet about online harassment and have a plan of action in place if trolling becomes serious

Protecting family and friends

Trolls and others looking for a journalist’s personal data can often find a lot of information from the unsecured social media accounts of those close to the journalist. Trolls may also target these people if they are unable to attack a journalist directly. Attacks can include the hacking of personal accounts, including bank accounts, identity fraud, as well as physical threats.CPJ has spoken with journalists who described how threats were sent to their relatives as well as to themselves.

To reduce the risk:

- Speak to your family and friends about trolling and online harassment and the possible consequences

- Sign up family members to a service that will remove their personal data from data broker sites. You will need to set up a continuous subscription if you want their data to continue to be removed. Be aware that these services remove data from the most common data broker sites and it is likely that their personal information will continue to exist on the internet in some form

- Work with them to remove photos and posts related to you on their social media sites

- Speak with family and friends about their own photos and how they can use privacy settings to limit who has access to them

- Make them aware that posting about you or tagging you in photos and posts could put both you and them at risk

- Ask them to consider making their accounts private during times when you expect increased levels of trolling

- Ask them to make their friends list private

- Consider unlinking your social media profiles from their accounts

- Family members should remove personal information from their sites, such as their date of birth, email, and phone numbers

- Secure their accounts by asking them to use a password manager to create long, unique passwords, and by setting up two-factor authentication (2FA)

During an attack

- Be vigilant for signs of hacking of your accounts. Ensure that you are using a password manager and have long, unique passwords for your accounts. Turn on two-step authentication

- Journalists should try not to engage with the trolls as this can make the situation worse

- Review your social media accounts for comments that may indicate that an online threat is about to turn into a physical threat. This could include people posting your address online and calling on others to attack you and/or increased harassment from a particular individual

- Document any comments or images that are of concern, including screenshots of the trolling, the time, the date, and the social media handle of the troll. This information may be useful at a later date if there is a police inquiry

- You may want to block or mute those who are harassing you online. You should report abusive content to social media companies and keep a record of your contact with these companies

- Try to ascertain who is behind the attack and their motives. The online attack may be linked to a story you recently published

- Inform your family, employees, and friends that you are being harassed online. Trolls may also target family members as part of their trolling campaign

- You may want to consider coming offline for a period of time until the harassment has died down

- Online harassment can be an isolating experience. Ensure that you have a support network that you can depend on to assist you which, in a best case scenario, will include your employer

Digital Safety: Identifying bots

Journalists covering elections are increasingly likely to be targeted online through campaigns that aim to discredit them and their work. Often it can be hard to determine who is behind a sustained online attack. Attackers can be real people or malicious computer bots: accounts that are run by computers rather than humans. Bots mimic human behavior on social media accounts as a way to spread misinformation or propaganda that support their cause. There can be an increase in the use of bots during events, such as elections, or during times of crisis, such as COVID-19. Identifying bots from real people can help journalists to better understand the harassment and identify when a digital threat may become physical.

How to identify a bot

There are several techniques that journalists can use to try to identify bots.

- Look at the accounts of the people harassing you online and check to see what year their accounts were created. An account that was set up recently or was inactive for a long period and has only recently started posting content may be a bot

- Check the personal details of the person behind the account, such as location or date of birth. A lack of personal information or nothing written in a bio can often mean that the account is a bot

- The user’s photo can often help a journalist to tell if the account is real or not. Fake accounts may not have a photo uploaded or they may be using a photo taken from stock images or an image taken from another fake account. Journalists can copy the image and upload it to a reverse image search program, such as Tineye, to see if the photo has been used elsewhere on the internet

- Look at the information posted from the account. If the user is retweeting a lot of content from other users or just posting content with a headline and a link then the account is likely to be fake. A bot is unlikely to interact with others on the social media site

- If the account has a low number of followers then it is most likely a bot

- Social media posts that have a low number of followers and a high number of likes or retweets are likely to be fake and part of a network of bot accounts

- Look at the accounts of those following the suspected bot and review the content they are posting. Bots are often programmed to publish identical content at the same time

- Check the name of the account and the Twitter handle (the part that starts with @). If the name and the handle do not match then the account may be fake

Journalists may want to mute or block bots who are attacking them online. Media workers are advised to report any malicious accounts to social media companies. It is recommended that you document any posts that are abusive or threatening, including screenshots of the accounts that are threatening you, the date of the comment, and any action you have taken. This information may be useful at a later date should you wish to pursue any legal action.

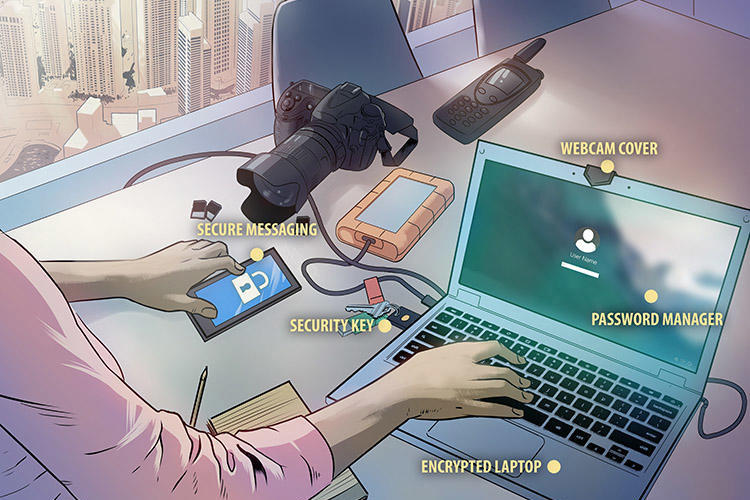

Digital Safety: Protecting your devices and materials

It is important to have best practice around securing your devices and securing materials. If a journalist is detained while covering the election process, their devices may be taken and searched, which could have serious consequences both for them and their sources

The following steps can help protect you and your information:

- Review what information is stored on your devices, including phones and computers. Anything that puts you at risk or contains sensitive information should be backed up and deleted. There are ways to recover deleted information so anything that is very sensitive will need to be permanently erased using a specific computer program and not just deleted

- When reviewing content on their phone journalists should check information stored on the phone (the hardware) as well as information stored in the cloud (Google Photos or iCloud)

- Journalists should check the content in messaging applications such as WhatsApp. They should save and then delete any information that puts them at risk. Media workers should be aware that WhatsApp backs up all content to the cloud service linked to the account, for example the iCloud or Google Drive

- Think about where you want to back up your information. You will need to decide whether it is safer to keep your materials in the cloud, on an external hard drive or on a USB

- Journalists should regularly move material off their devices and save it on the backup option of their choice. This will ensure that if your devices are taken or stolen then you have a copy of the information

- It is a good idea to encrypt any information that you back up. You can do that by encrypting your external hard drive or USB. You can also turn on encryption for your devices. Journalists should review the law in the country in which they are working to ensure they are aware of the legalities around the use of encryption

- If you suspect that you may be a target and that an adversary may want to steal your devices, including external hard drives, keep your hard drive in a place other than your home

- Put a PIN lock on all your devices: the longer the PIN the more difficult it is to crack

- Update your operating system when prompted to help protect devices against the latest malware

- Do not leave devices unattended in public, including when charging, to avoid them being stolen or tampered with

- Avoid plugging devices into public USB ports. Consider using a USB protector—a device that prevents data from being transferred to an external device—when you connect to a USB port

- Do not use USBs that are handed out free at events. These could include malware that could infect your computer

- Set up your phone or computer to remote wipe. This is a function that will allow you to erase your devices remotely, for example if your devices are taken by the authorities. This will only work if the device is able to connect to the internet

Digital Safety: Dealing with misinformation

During election time there is likely to be a lot of misinformation circulating online. Take the following steps to ensure that the information you are using or sharing is legitimate.

- Do a regular internet search for documented misinformation campaigns and attacks involving the election

- Think before using or sharing information, including photos and video. Consider the source and whether it is reputable

- Upload images to a reverse image search platform, such as Tineye. This will tell you when the image was first put online

- Avoid clicking on links or downloading documents on your phone. The small screen makes it difficult to properly analyze the source

- Go directly to the source of the information instead of downloading information sent to you via email, through SMS, or messaging apps. Look up the author of the information online to verify their identity and expertise

- Research the authors of unexpected messages or requests to take action and verify their identity. Reach out to them directly to confirm they sent the message if possible

- Use advanced search strategies, such as Boolean search methods, to look up information and confirm the source

- Be aware that websites from legitimate sources should be encrypted. You can check this by looking for https and a padlock icon at the start of the URL, or web address, in your browser. This means that traffic between you and the site is encrypted

- Be wary of information that is shared in group chats on WhatsApp and other messaging services. There is a lot of misinformation being passed around and some of it may also contain malware

Other safety resources for journalists and newsrooms covering the 2020 U.S. elections

Safety manuals and guides

- DIY digital safety guides (CPJ)

- Handbook for Journalists During Elections (2015 Edition)(Reporters Without Borders / Organisation Internationale de la francophonie)

- Freelance Journalist Safety Checklist (ACOS Alliance)

- News Organizations Safety Self-Assessment (ACOS Alliance)

Insurance

Training

- HEFAT course for women journalists on the political beat (IWMF)

- Training and resources for journalists in an age of disinformation (First Draft)

Legal Support

- Election Legal Guide(Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press)

- Journalists who need legal assistance can contact the Reporters Committee hotline through its web form (which is the fastest way) or by calling 1-800-336-4243

Digital Safety Preparedness