South Africa, one of the media freedom beacons in sub-Saharan Africa, will hold national and provincial elections on May 8. As the country celebrates 25 years of democracy, the press in South Africa faces old and new challenges, including physical harassment and cyber bullying. The press freedom environment, including the safety of journalists, will be one of the key indicators for the health of the country’s democracy and the freeness and fairness of its polls.

CPJ’s Emergencies Response Team (ERT) has compiled a Safety Kit for journalists covering South Africa’s election. The kit contains information for editors, reporters, and photojournalists on how to prepare for the election and how to mitigate digital, physical and psychological risk.

Journalists requiring assistance can contact CPJ via emergencies@cpj.org.

CPJ’s Journalist Security Guide has additional information on basic preparedness and assessing and responding to risk. CPJ’s resource center has additional information and tools for pre-assignment preparation and post-incident assistance.

Menu:

- Editor’s Safety Checklist

- Physical Safety: Covering rallies and protests

- Physical Safety: Covering hostile communities

- Physical Safety: Covering crime

- Digital Safety: Basic device preparedness

- Digital Safety: Identifying bots

- Digital Safety: Online harassment

- Digital Safety: Securing and storing materials

- Psychological Safety: Managing trauma in the newsroom

- Psychological Safety: Trauma-related stress

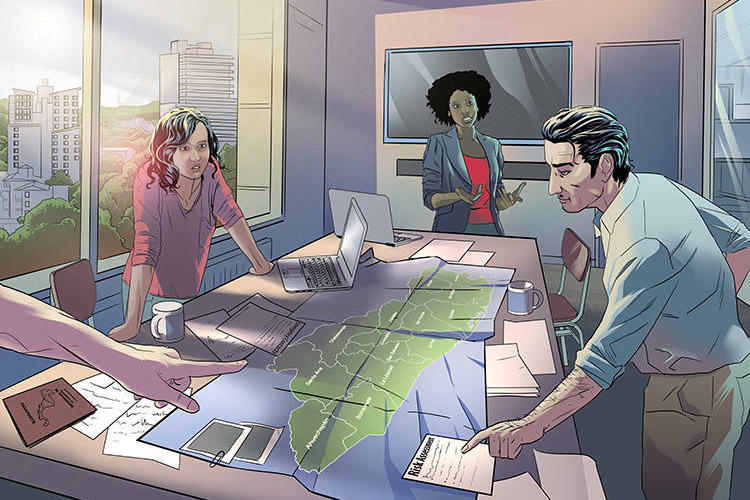

Editor’s Safety Checklist when deploying staff on a hostile story

During the run up to the election, editors and newsrooms will be assigning journalists to stories at short notice. This checklist includes key questions and steps to consider, to reduce risk for staff.

- Are your staff experienced enough for the assignment?

- Have you discussed any health issues your staff may have that could affect them during the task?

- Have you recorded and saved securely the emergency contacts of all staff being deployed?

- Does the team have the appropriate accreditation, press passes, or a letter indicating they work for your organization?

- Have you considered the level of risk attached to the story that your team may be exposed to? Is this level of risk acceptable in comparison to the editorial gain?

- Detail potential risks and measures put in place to make staff safer:

- Does the role or profile of any journalist being deployed put them at more risk? ( E.g. photojournalists who work closer to the action or female journalists.)

If yes, provide detail:

- Is special equipment such as body armor, respirators, or a medical kit required? Do the journalists have access to the necessary equipment and do they know how to use it?

- Are the journalists driving themselves and, if so, is their vehicle roadworthy and appropriate?

- Have you identified how you will communicate with the team and how they will remove themselves from a situation if necessary? If so, detail below:

- Have you identified the local medical facilities in case of injury? If so, record it below:

- Is the team correctly insured and have you put in place appropriate medical cover?

- Have you considered the possibility of long-term trauma-related stress?

For more information about risk assessment and planning, see the CPJ Resource Center.

Physical Safety: reporting safely on rallies and protests

During elections, journalists frequently cover rallies, campaign events, and protests. CPJ is aware of incidents in South Africa where journalists were verbally abused or physically assaulted while covering rallies and events in 2018. Some were denied access to political events.

To minimize the risk:

Political Events and Rallies

- Ensure that you have the correct accreditation or press identification. For freelancers, a letter from the commissioning employer is helpful. Have it on display only if safe to do so. Do not use a lanyard, but clip it to a belt.

- Gauge the mood of the crowd. If possible, call other journalists already at the event to check the mood. Consider taking another reporter or photographer with you if necessary.

- Wear clothing without media company branding and remove media logos from equipment/vehicles if necessary. Have appropriate footwear.

- Have an escape strategy in case circumstances become hostile. You may need to plan this on arrival, but do so before beginning the assignment. Park your vehicle in a secure location or ensure you have a guaranteed mode of transport.

- If the climate becomes hostile, do not hang around outside the venue/event and do not start questioning people.

- If the objective is to report from outside, working with a colleague is sensible. Report from a secure location with clear exits and familiarize yourself with the route to your transportation. If an assault is a realistic prospect, consider the need for security and minimize your time on the ground to what is absolutely necessary.

- Inside the event, report from the press area unless it is safe to do otherwise. Ascertain if the security or police will assist if you are in distress, and identify your exits.

- If the crowd/speakers are hostile to the media, mentally prepare for verbal abuse. In such circumstances, just do your job and report. Do not react to the abuse. Do not engage with the crowd. Remember, you are a professional even if others are not.

- If spitting or small missiles from the crowd are a possibility and you are determined to report, consider wearing a hooded, waterproof, and discrete bump cap.

- If the task was difficult, do not bottle up your emotions. Tell your superiors and colleagues. It is important that they are prepared and that everyone learns from each other.

Protests

Municipal IQ, a specialized local government data and intelligence organization, recorded 237 protests against municipalities across South Africa in 2018. This was an increase from the previous record of 191 protests in 2014. For more data view the Institute for Security Studies‘ maps of incidents of public violence across South Africa.

To minimize the risk when covering protests:

- Plan the assignment and ensure that you have a full battery on your mobile phone. Know the area you are going to. Work out in advance what you would do in an emergency. Take a medical kit if you know how to use it.

- Always try to work with a colleague and have a regular check-in procedure with your base, particularly if covering rallies or crowd events.

- Wear clothing and footwear that allows you to move swiftly. Avoid loose clothing and lanyards that can be grabbed, as well as any flammable material (i.e. nylon).

- Consider your position. If you can, find an elevated vantage point that might offer greater safety.

- At any location, always plan an evacuation route as well as an emergency rendezvous point if you are working with others. Know the closest point of medical assistance.

- Maintain situational awareness at all times and limit the number of valuables you take. Do not leave any equipment in vehicles, which are likely to be broken into. After dark, the criminal risk increases.

- If working in a crowd, plan a strategy. It is sensible to keep to the outside of the crowd and don’t get sucked into the middle where it is hard to escape. Identify an escape route, and have an emergency meeting point if working with a team.

- Photojournalists generally have to be in the thick of the action so are at more risk. Photographers in particular should have someone watching their back and should remember to look up from their viewfinder every few seconds. To avoid the risk of strangulation, do not wear the camera strap around your neck. Photojournalists often do not have the luxury of being able to work at a distance, so it is important to minimize the time spent in the crowd. Get your shots and get out.

- All journalists should be conscious of not outstaying their welcome in a crowd, which can turn hostile quickly.

- South African police have used live fire and rubber bullets to quell protesters. Consider using personal protective equipment, but if this is not appropriate, pay attention to the police. If firearms are visible, move to hard cover and do not dwell in natural exits in case of a stampede.

To minimize the risk when dealing with tear gas:

- You should wear personal protective equipment that includes a gas mask, eye protection, body armor, and helmet.

- Individuals with asthma or respiratory issues should avoid areas where tear gas is being used. Likewise, contact lenses are not advisable. If large amounts of tear gas are being used, there is the possibility of high concentrations of gas sitting in areas with no movement of air.

- Take note of any potential landmarks (i.e. posts, curbs) that can be used to help you navigate out of the area if you are struggling to see.

- If you are exposed to tear gas, try to find higher ground and stand in fresh air to allow the breeze to carry the gas away. Do not rub your eyes or face as this may worsen the situation. Once possible, shower in cold water to wash the gas from skin, but do not bathe. Clothing may need to be washed several times to remove the crystals completely or even discarded.

Journalists have been assaulted by protesters in South Africa and targeted by criminals. When dealing with aggression, consider the following:

- Gauge the mood of protesters toward journalists before entering any crowd, and watch for potential assailants.

- Read body language to identify an aggressor and use your own body language to pacify a situation.

- Keep eye contact with an aggressor, use open hand gestures and keep talking with a calming manner.

- Keep an extended arm’s length from the threat. Back away and break away firmly without aggression if held. If cornered and in danger, shout.

- If aggression increases, keep a hand free to protect your head and move with short deliberate steps to avoid falling. If in a team, stick together and link arms.

- While there are times when documenting aggression is crucial journalistic work, be aware of the situation and your own safety. Taking pictures of aggressive individuals can escalate a situation.

- If you are accosted, hand over what the assailant wants. Equipment it is not worth your life.

Physical Safety: reporting safely in a hostile community

Journalists are frequently required to report in areas or communities that are hostile to the media or outsiders. This can happen if a community perceives that the media does not fairly represent them or portrays them in a negative light. During an election campaign, journalists may be required to work for extended periods among communities that are hostile to the media.

To help reduce the risk:

- If possible, research the community and their views. Develop an understanding of what their reaction to the media will be, and adopt a low profile if necessary.

- Wear clothing without media company branding and remove media logos from equipment/vehicles if necessary. Have appropriate clothing and footwear.

- Take a medical kit if you know how to use it.

- Secure access to the community. Turning up without an invitation or someone vouching for you can cause problems. Hire or get the approval of a local fixer, community leader or person of repute in the community who can help coordinate your activities. Identify a local power broker who can help in case of emergency.

- At all times, be respectful to the individuals and their beliefs/concerns.

- Avoid working at night: the risk increases dramatically.

- If there is endemic abuse of alcohol or drugs in the community, the unpredictability factor increases.

- Limit the amount of valuables/cash that you take. Will thieves be attracted by your equipment? If you are accosted, hand over what they want. Equipment is not worth your life.

- Ideally, work in a team or with back up. Depending on risk levels, the backup can wait in a nearby safe location (shopping mall/petrol station) to react if necessary.

- Plan your visit. Think about the geography of the area and plan accordingly.

- Park your vehicle ready to go, ideally with the driver in the vehicle.

- If you have to work remotely from your transportation, know how to get back to it. Identify landmarks and share this information with colleagues.

- Know where to go in case of a medical emergency and work out an exit strategy.

- Consider the need for security if the risk is high. A local hired back watcher to protect you/your kit can be attuned to a developing threat while you are concentrating on work.

- It is generally sensible to ask consent before filming/photographing an individual, particularly if you do not have an easy exit.

- When you have the content you need, get out and do not linger longer than necessary. It is helpful to have a cut off time pre-agreed and pull out at that time. If a team member is uncomfortable, do not waste time having a discussion. Just leave.

- Before broadcast/publication consider that you may need to return to this location. Will your coverage affect your welcome if you return?

Physical Safety: Reporting safely on a crime scene or in an area of high crime

Being aware of the criminal threat is second nature in South Africa. However, journalists are particularly vulnerable as they often work in high crime areas or report on crime scenes. Expensive equipment can make journalists attractive targets. In 2015, a SABC correspondent was mugged live on air while reporting from outside a Johannesburg hospital. In January, a News24 journalist was mugged and his camera stolen while covering voter registration in Cape Town.

To minimize the risk:

- Research the locations you will be working in and understand the dynamics before going in. Adapt your plans accordingly.

- A useful resource for identifying local police stations and crime hot spots is the Institute of Strategic Studies’ crime hub website.

- Avoid working at night in high crime areas but if you have to, make sure you have other people with you.

- Ensure you have an understanding of the area’s geography so that routes in/out can be assessed for potential problems such as dead ends or choke points. The nearest suitable point of assistance/medical facilities should be identified and access routes established pre-departure.

- Maintain a low profile. Overt displays of wealth should be avoided, in particular wearing jewelry or watches, or openly carrying expensive items such as cameras and phones.

- Decide on a sensible amount of cash to carry and where best to carry any money/credit cards.

- Consideration should be given to establishing trusted contacts in the area you intend to visit, who can provide advice or assistance.

- Do not use the phone openly on public roads and streets. It is inviting an assault.

- Setting up a reporting position should be considered carefully. Always have clear exits, cover and individuals around you, protecting you from assault. If there are visible criminal elements in the vicinity consider a different location.

- Time on task should be minimized. Get in, get what you need, get out. More than 15 to 20 minutes on the ground increases vulnerability.

- A communications plan should be in place throughout to ensure regular check-ins between those on task and their primary points of contact. An alarm procedure should be established.

- If reporting on a crime, consider the feelings of the community/victims. Treat them with respect and where possible, agree consent to be interviewed or photographed.

- If accosted, it is generally advisable to comply in full with the criminal’s demands rather than attempt to fight back.

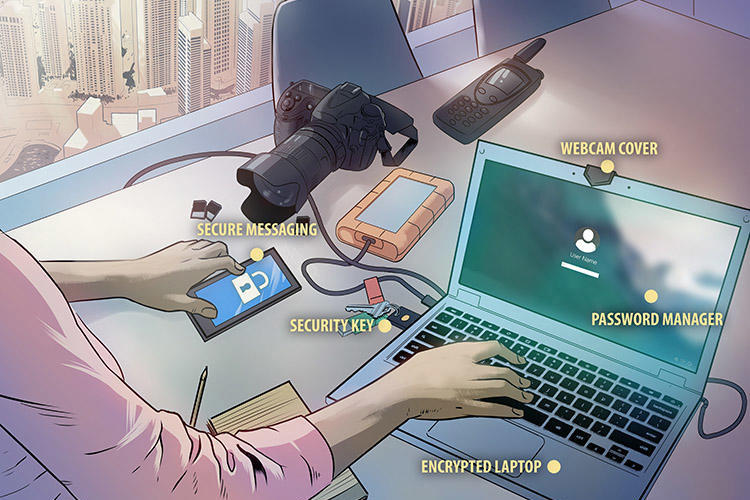

Digital Safety: Basic device preparedness

Before going out on assignment it is good practice to:

- Backup your devices to a hard drive and remove any sensitive data from the device you are carrying.

- Log out of any accounts, apps and on all of your browsers and clear your browsing history. This will stop people being able to access your personal and work accounts, such as email and social media sites.

- Password protect all your devices and set up your devices to remote wipe. Remote wipe will work only with an internet connection.

- Take as few devices with you as possible. If you have spare devices you should take them instead of personal or work devices.

Digital Safety: Identifying bots

Journalists covering elections are increasingly likely to be targeted online through smear campaigns that aim to discredit them and their work. It can be hard to work out who is behind a campaign or attack. Attackers can be real people or malicious computer bots–accounts that are run by computers rather than humans. Bots mimic human behavior on social media accounts as a way to spread misinformation or propaganda that support a cause. Identifying bots from real people can help journalists to better understand the harassment and identify when a digital threat may become physical.

To identify a bot:

- Look at the accounts of the people harassing you online and check to see the year in which they were created. An account that was set up recently or inactive for a long period of time that has only recently started posting content may be a bot.

- Check the personal details of the person behind the account, such as location or date of birth. A lack of personal information or an empty bio can often mean that the account is a bot.

- Fake accounts may not have a user photo uploaded or they may be using a photo taken from stock images or an image taken from another fake account. Journalists can copy the image and upload it to Google images to see if the photo has been used elsewhere on the internet.

- Look at the information posted from the account. If the user is retweeting a lot of content from other users or just posting content with a headline and a link then the account is likely to be fake. A bot is unlikely to interact with others on the social media site.

- If the account has a low number of followers then it is most likely a bot.

- Social media posts that have a low number of followers but a high number of likes or retweets are likely to be fake and part of a network of bot accounts.

- Look at the accounts of those following the suspected bot and review the content they are posting. Bots are often programmed to publish identical content at the same time.

- Check the name of the account and the Twitter handle (the part that starts with @). If the name and the handle do not match, then the account is usually fake.

Journalists may want to mute or block bots that attack them online. Media workers are advised to report any malicious accounts to social media companies. It is recommended to document any posts that are abusive or threatening, including screenshots of the accounts, the date of the comment, and any action you have taken. This information may be useful at a later date should you wish to pursue any legal action.

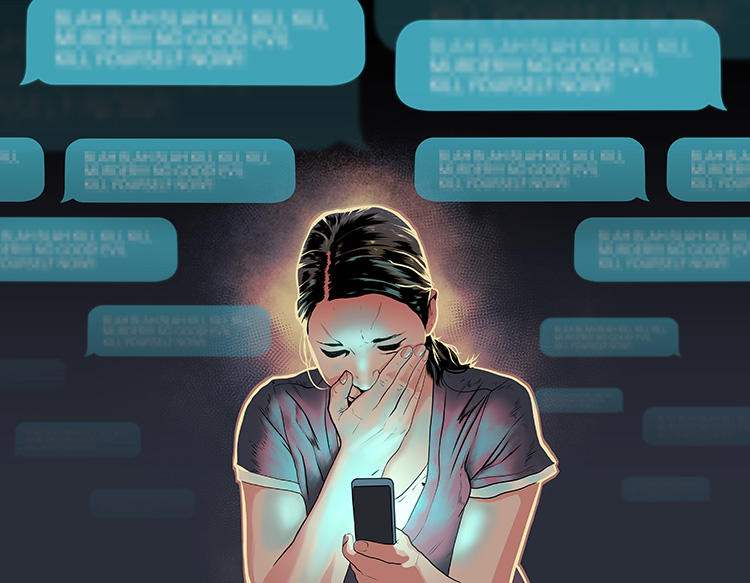

Digital Safety: Online harassment and trolling

Journalists may face an increased level of online harassment during election time and should take steps to protect themselves and their accounts. Similar to other parts of the world, female journalists in South Africa have been subject to online abuse and trolling from the public and members of political parties. If trolling becomes the norm, it encourages a climate favorable to violence against the media. Journalists should monitor social media accounts regularly for increased levels of trolling or signs that an online attack may become a physical threat.

To minimize the risk:

- Create long and strong passwords for your accounts. These should be between six to eight words and you should make a unique password for each account. Consider using a password manager, which is currently the most secure way of managing passwords. This will help to prevent accounts from being hacked.

- Turn on two-factor authentication (2FA) for accounts.

- Review your privacy settings for each account and make sure any personal data, such as phone numbers and date of birth, is removed. Lock down the privacy settings for each of your accounts.

- Look through your accounts and remove any photos or images that could be manipulated and used as a way to discredit you. This is a common technique used by trolls.

- Consider getting your account verified by the social media company. This is a blue tick alongside your name confirming that the account is yours. This will help others to identify your account from fake accounts set up in your name.

- Monitor your accounts for signs of increased trolling activity or for indications that a digital threat could become a physical threat. Be aware that certain stories are likely to attract higher levels of harassment.

- Speak with family and friends about online harassment. Trolls often obtain information about journalists via the social media accounts of their relatives and social circle. Consider asking people to remove photos of you from their sites or lock down accounts.

- Speak with your media outlet about online harassment and have a plan of action in place if trolling becomes serious.

During an attack:

- Journalists should try not to engage with trolls as this can make the situation worse.

- Try to ascertain who is behind the attack and their motives. The online attack may be linked to a story you have recently published.

- Journalists should report any abusive or threatening behavior to the social media company.

- Document any comments or images that are of concern, including screenshots of the trolling, the time, the date, and the social media handle of the troll. This information may be useful at a later date if there is a police inquiry.

- Be vigilant for signs of hacking. Ensure that you have strong and long passwords for each account and have turned on two-step authentication.

- Inform your family, employees, and friends that you are being harassed online. Adversaries will often contact family members, and your workplace and send them information/images in an attempt to damage your reputation.

- You may want to block or mute those who are harassing you online. You should also report any abusive content to social media companies and keep a record of your contact with these companies.

- Review your social media accounts for comments that may indicate that an online threat is about to turn into a physical threat. This could include people posting your address online (known as doxing) and calling on others to attack you and/or increased harassment from a particular individual.

- You may want to consider coming offline for a period of time until the harassment has died down.

- Online harassment can be an isolating experience. Ensure that you have a support network to assist you which, in a best case scenario, will include your employer.

Digital Safety: Securing and storing materials

It is important to have good protocols around the storing and securing of materials during election times. If a journalist is detained while covering an election campaign, their devices may be taken and searched which this could have serious consequences for the journalist and their sources.

The following steps can help protect you and your information.

- Review what information is stored on your devices, including phones and computers. Anything that puts you at risk or contains sensitive information should be backed up and deleted. There are ways to recover deleted information, so anything that is very sensitive will need to be permanently erased using a specific computer program rather than just deleted.

- When reviewing content on a smartphone, journalists should check information stored on the phone (the hardware) as well as information stored in the cloud (Google Photos or iCloud).

- Journalists should check the content in messaging applications, such as WhatsApp. They should save and then delete any information that puts them at risk. Media workers should be aware that WhatsApp backs up all content to the cloud service linked to the account, for example iCloud or Google Drive.

- Think about where you want to back up information. You will need to decide whether it is safer to keep your materials in the cloud, on an external hard drive or on a USB.

- Journalists should regularly move material off their devices and save it on the backup option of their choice. This will ensure that if your devices are taken or stolen then you have a copy of the information.

- It is a good idea to encrypt any information that you back up. You can do that by encrypting your external hard drive or USB. You can also turn on encryption for your devices. Journalists should review the law in the country they are working in to ensure they are aware of the legalities around the use of encryption.

- If you suspect that you may be a target and that an adversary may want to steal your devices, including external hard drives, then you should keep your hard drive in a place other than your home.

- Put a PIN lock on all your devices. The longer the PIN, the more difficult it is to crack.

- Set up your phone or computer to remote wipe. This is a function that will allow you to erase your devices remotely, for example if your devices are taken by the authorities. This will only work if the device is able to connect to the internet.

Psychological Safety: Managing trauma in the newsroom

Stories and situations that frequently result in distress and when you should be thinking about trauma include:

- Graphic images of violence (death, crime scenes, brushes with death)

- Large scale accidents or disasters (train/plane/car crashes)

- Abuse cases, particularly involving children or the elderly

- Any distressing story that has a personal connection for staff

- When inexperienced staff are being exposed to such content for the first time.

Management should guide staff on such days and share the responsibility of care. The following approach should be considered and acted upon if required. The extent to which the guidance is implemented will depend on the severity of story.

On such days:

- Try to rotate assignments around staff so that the same producer isn’t cutting footage on difficult subjects for days on end.

- Make sure that team members know that they can say no when a subject is personally distressing to them. Staff should feel able to express concerns about tackling challenging subjects, and it should be handled with sensitivity and discretion, and without further questions being asked. This represents an important exception to how videos are generally assigned.

- Make sure that your team members have breaks in between edits and are able to get fresh air when working on difficult material.

- Ask people if they are OK early and often–and not just via text message. You should check-in with your staff at least once or twice a day verbally to make sure that everyone knows you are available to chat. Conversation between staff on the issue should be encouraged.

- If your team isn’t involved in these areas, be generous with lending team members to help out other teams during particularly stressful periods.

- On particularly stressful days, try to ensure there is a debrief before everyone leaves the work environment.

- At the debrief, the responsible manager should acknowledge that people may be distressed by the story and it’s perfectly natural in the short term. If staff are affected they should talk to one of their managers. Talking to their colleagues can also help.

- If they would rather speak to an impartial adviser in confidence, is there an employee assistance program (EAP) or counsellor they can speak to?

Psychological Safety: Dealing with trauma-related stress

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been increasingly acknowledged as an issue confronting journalists who cover distressing stories.

Traditionally, the issue is associated with journalists and media workers in conflict zones or when they are exposed to near death or highly threatening situations. However, more recently, there is a greater awareness that journalists working on any sort of distressing story can experience symptoms of PTSD. Stories involving abuse or violence (crime scene reporting, criminal court cases or robberies) or stories that involve a large loss of life (car crashes/mine collapses) are all potential causes of trauma among those covering them. Those being abused online or trolled are also vulnerable to stress-related trauma.

The growth of uncensored user-generated material has created a digital front line. It is now recognized that journalists and editors viewing traumatic imagery of death and horror are susceptible to trauma. This secondary trauma is now known as vicarious trauma.

It is important for all journalists to realize that suffering from stress after witnessing horrific incidents/footage is a normal human reaction. It is not a weakness.

For everyone:

- Talk about it. Everyone from senior management to the most junior producers are affected by dealing with difficult events, graphic footage, or challenging conditions. Talk to your manager or to another supervisor, talk to the person you sit next to. Don’t suffer in silence.

- Remember it’s not in any way career-limiting to say that you need a break either in between videos, from a particular story, or from working in the field.

- Don’t look at graphic footage before you sleep, and don’t hit the bar too hard after a difficult news day. Disrupted sleep can harm the recovery process.

- Exercise and meditation are your friends here, as is maintaining a healthy diet and staying well hydrated.

- Remember that video doesn’t have to be graphic to be distressing. Footage involving blood or violence requires obvious care, but particularly emotive testimony can also be draining, as can videos of verbal abuse. Different people find different things challenging and distressing, so be sensitive.

- Take your comp days if you’ve worked through weekends or significantly over your hours on multiple days, whether editing or in the field. Take at least some of them quickly because you need to spend that time recovering.

For editing producers:

- Don’t watch more than you need to. Certain upsetting footage will be broadcast, but don’t watch it because you feel you have to prove yourself. Have conversations with your supervisor or manager early on about how to treat the footage so you don’t have to watch it over and over, only for it to get cut.

- When showing your supervisor, a manager, or a member of the legal team a particularly graphic or distressing video, always forewarn what they are looking at. E.g. “Do you mind looking at a video showing the immediate aftermath of a violent attack?” rather than “Do you mind looking at my video?” Footage is always significantly more upsetting if you don’t know what’s coming.

- Develop a routine. Something as simple as putting both feet firmly on the floor, taking deeper breaths than normal just before watching something particularly difficult, and having a stretch afterwards can work. Find a routine that work for you.

- If you have a project that requires continued daily exposure to difficult footage, then talk about it. Acknowledge the effect that it’s having on you, and think actively about how you’re going to look after yourself while you do that work.

For producers in the field:

- Remember, it’s perfectly normal to feel helpless or upset that you couldn’t do more when covering upsetting stories. Just acknowledge how you’re feeling to your colleagues, or someone else you feel comfortable with. Talking about it rather than avoiding it is often the key.

If it’s particularly intense:

- It’s normal to feel jumpy or anxious, or to replay difficult images in your mind immediately after an event. Admitting how you’re feeling is useful, as is taking a bit of time out, even it’s just a short break.

- If these feelings aren’t passing in the days and weeks after the events, it’s worth flagging it to your seniors. If it feels particularly overwhelming, it’s better to seek help sooner.