CPJ calls on reporters to share stories of being stopped at U.S. border

CPJ has issued a call to journalists to share any difficulties they have had while crossing the U.S. border. We partnered with Reporters Without Borders, or RSF, in this project and have created a page on our website where journalists can submit their cases.

CPJ, RSF, the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, and other partner groups have documented at least 24 cases of journalists being stopped at the border since 2008. Many of them were asked to unlock and turn over their cell phones, which poses a risk to their confidential sources and unpublished work.

CPJ Insider spoke with CPJ North America Program Coordinator Alexandra Ellerbeck to learn more about the project.

Why do device searches pose a threat to journalists?

It’s incredibly important that journalists’ data remain private. A journalist’s device may contain sensitive information, including the identities of sources who require anonymity for safety reasons. Others who are interested in the information may also try to censor the story or otherwise retaliate.

Are device searches legal?

A person’s belongings cannot be searched without probable cause in the U.S. However, the Supreme Court has recognized an exception to the usual standard of probable cause for searches at the border. U.S. Customs and Border Protection has interpreted this to mean it has the right to search electronic devices without probable cause.

But CPJ believes there is a distinction between belongings and electronic devices. Unlike tangible items–food or clothing–electronic devices contain multitudes of intangible data. To search a person’s bag for contraband is one thing; to search a person’s cell phone or computer is another thing entirely. Its implications for privacy are very different and far more consequential–especially for journalists.

In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court has drawn this distinction in at least one instance. It ruled in 2014’s California v. Riley that the search and seizure of the digital contents of a person’s devices during an arrest without probable cause is unconstitutional.

Why is CPJ gathering journalists’ experiences?

This is one of the first efforts to record journalists’ difficulties at the U.S. border. We had known that border stops and device searches have increased under President Trump, but had no data with which to measure its impact on the press. Now, with that data, we hope to become better informed and better equipped to uphold press freedom in the U.S.

Journalists, help us by sharing your experiences at the U.S. border! Click here to submit your case.

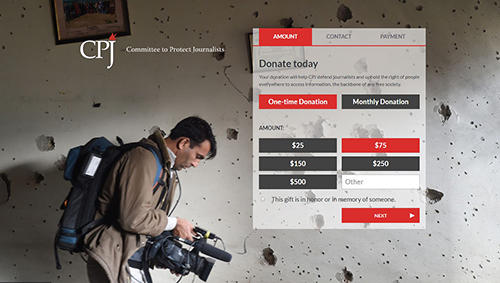

Help secure CPJ’s future: Sign up to become a monthly donor

CPJ can’t do its work without you.

With your support, CPJ can work to release imprisoned journalists and provide them and their families with the assistance they need. Your donation helps support the vital work of CPJ’s broad network of correspondents and representatives based in more than a dozen countries around the world. Your support enables CPJ to publish special reports on the climate for press freedom in countries like Iran, Pakistan, and Ecuador. Your generosity also helps CPJ advocate with elected leaders on Capitol Hill on behalf of journalists reporting in the United States.

Become a monthly donor to CPJ today and join the ranks of press freedom defenders all over the world. From $5 to $500, every dollar you donate helps CPJ make a difference in the lives of journalists everywhere.

CPJ launches special report on Iran

In a special report published in late May, CPJ found that despite promises of reform by Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, little has changed for journalists working in the country.

Here, CPJ Insider spoke to CPJ Middle East and North Africa Program Coordinator Sherif Mansour, who told us more about the report and its launch.

Why did CPJ publish a special report on Iran?

For several reasons–CPJ hadn’t done a report on Iran since 2013 and we wanted to capture the changes to the country’s media landscape under its new president, Hassan Rouhani, who publicly committed to press-related reforms.

In our report, we wanted to highlight the reforms Rouhani has been able to implement, especially in connection with the internet and smartphones. He also added a layer of protection that allows Iranian journalists to disseminate the news in spite of long-standing censorship. We wanted to note the decline of imprisoned journalists in the country, which fell from 45 at the height of former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s crackdown to five in our most recent census.

CPJ saw an opening to include press freedom as part of the diplomatic negotiations with European policymakers. The message we had and continue to have is that press freedom and human rights were put aside in 2015 in order to pass the Iran Deal and with the intention of having follow-up conversations. This was done by both the Rouhani administration and other European and American policymakers. Three years later, we’re in the same place.

Tell me about the launch of the report.

We launched the report at European Parliament in Brussels. It included policymakers from Parliament and other European institutions, many whom we’ve already met in person. It was hosted by Dutch MEP Marietje Schaake, one of Parliament’s leading advocates against online censorship who has pressed for including human rights in dialogue with Iranian officials. She is part of Iran’s Task Force and has visited the country twice. After the report launch, she wrote a blog post for her website in which she said it was “crunch time” for Iran.

What’s next?

European policymakers are faced with the challenge of working directly not just to save the Iran Deal but also to establish their own bilateral policy with Iran outside of the United States. Whether it’s the nuclear deal, or trade negotiations, or official visits, we hope this will be on the agenda.

It doesn’t matter where the meetings happen–Brussels, Vienna, Tehran. With any engagement with Iranian officials, human rights must be on the agenda and must be explicit. There’s no table big enough to be ideal for human rights discussions and no table small enough to exclude it.

The best guarantee for the Iranian people is to express themselves directly, to let them practice their own freedom of speech, to let the media debate the country’s future, and to decide for themselves which direction they want to go.

League of Women Voters honors CPJ with award

CPJ is thrilled to announce that the League of Women Voters of the City of New York Education Fund is awarding CPJ with its 2018 Distinguished Service Award. CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon will accept the award. After the ceremony, he and Sarah Bartlett, dean of the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism, will have a discussion on press freedom.

The awards breakfast will take place on June 21 at 8 a.m. at the Roosevelt Hotel. Click here to attend.

CPJ hosts Ethiopian journalist at celebratory event in New York

In late May, CPJ hosted a reception for Eskinder Nega, an Ethiopian journalist who spent nearly seven years behind bars. Eskinder was released from prison in February.

CPJ and other groups campaigned for years for Eskinder’s release. He was featured in every prison census published by CPJ since his arrest in 2011. Click here to check out a video interview CPJ did with him.

CPJ and the Columbia Journalism Review highlight murders of Afghan journalists

Twenty-eight-year-old Maharram Durrani was supposed to start work at her new job on May 15. She was interested in covering issues related to women’s rights and had landed a role on a weekly women’s program on Radio Azadi.

Durrani never got to start work. She and eight other journalists were killed in a double suicide blast in Kabul on April 30, the deadliest day for journalists in Afghanistan since the fall of the Taliban. That same day, 100 miles away, a BBC reporter was shot dead by a group of armed men.

CPJ collaborated with the Columbia Journalism Review to publish a story that highlights the lives and work of the journalists who died on April 30. The team interviewed the journalists’ families, friends, and colleagues for the piece, which is striking in the stories it tells.

Check it out here: “One deadly day: Afghanistan’s murdered journalists, in the words of the people who knew them.”

Must-reads

- CPJ published an alert in early June condemning the murder of music journalist Zachary Stoner in Chicago, Illinois. Stoner, who published YouTube videos that focused on community life and hip hop artists in the city, was shot to death.

- The dangers of covering natural disasters were put in stark relief in late May, with the tragic deaths of U.S. journalists Mike McCormick and Aaron Smeltzer, who were reporting on a storm in South Carolina when a tree struck their car. CPJ’s Journalist Security Guide contains tips and advice for journalists on how to cover natural disasters, from earthquakes to hurricanes.

- In a blog post in late May, CPJ explored the many questions raised after Ukrainian authorities staged the death of a journalist with the stated aim of saving the journalist’s life. However, as CPJ’s Europe and Central Asia program coordinator, Nina Ognianova, put it, “This extreme action by the Ukrainian authorities has the potential to undermine public trust in journalists and to mute outrage when they are killed.”

- The Democratic National Committee, the governing body of the Democratic Party, announced in April that it would sue WikiLeaks and Julian Assange for their alleged involvement in the theft and dissemination of DNC computer files. But, as CPJ’s U.S. correspondent, Avi Asher-Schapiro wrote in a blog post, doing so could endanger the principles of U.S. press freedom.

- Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo have spent nearly five months behind bars in Myanmar, each arrested while investigating a mass killing of Rohingya men in September. CPJ’s Asia research associate, Aliya Iftikhar, conducted an interview with Reg Chua, the chief operating officer of Reuters Editorial in New York, about why it was so important for Reuters to publish the story the journalists were working on.

CPJ in the news

“How Trump’s ‘Fake News’ mantra metastasized worldwide,” The Daily Beast

“21 journalists in six countries jailed on charges related to ‘fake news’ in 2017,” The Hill

“Under guise of combating ‘fake news,’ foreign governments target their critics,” ABC News

“The UN celebrates press freedom with censorship,” New York Post

“Europe’s journalists are at risk. Here’s what the EU could do to protect them,” The Washington Post

“Why I have hope for journalists,” CNN

“World Press Freedom Day: Are journalists increasingly under attack?” BBC News

“Iran will lose its war against free expression,” The Washington Post

“10 deaths are reminder that a free press is not free,” The Columbus Dispatch

“Keeping a free and fair press is one of the defining political issues of our age,” The Guardian