In 1993, WILK radio host Frederick Vopper broadcast a conversation intercepted by an illegal wiretap and sent anonymously to the Pennsylvania radio station, in which two teachers union officials discussed violent negotiating tactics. The officials sued Vopper, arguing that he should be liable for the illegal wiretap that captured their comments. But the Supreme Court disagreed. As Justice John Paul Stevens wrote in the Bartnicki v. Vopper decision, “A stranger’s illegal conduct does not suffice to remove the First Amendment shield from speech about a matter of public concern.”

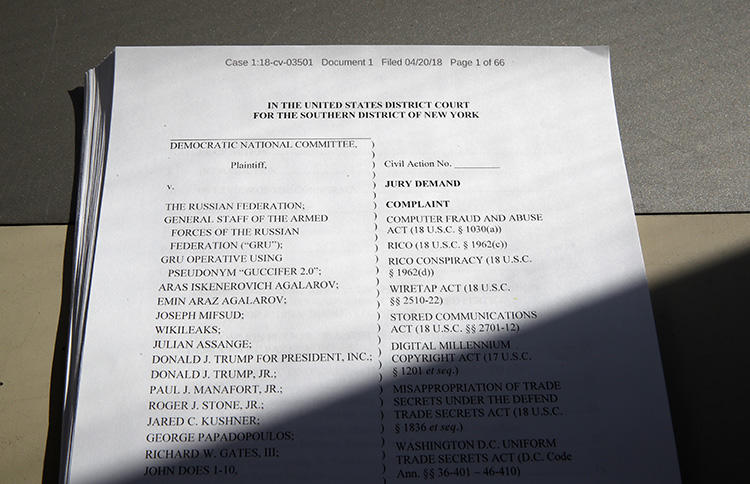

In April, the Democratic National Committee, the governing body of the Democratic Party, announced that it was suing WikiLeaks and Julian Assange–along with a number of other defendants, including the Trump campaign and Russian operatives–for their alleged involvement in the theft and dissemination of DNC computer files during the 2016 election. On its surface, the DNC’s argument seems to fly in the face of the Supreme Court’s precedent in Bartnicki v. Vopper that publishers are not responsible for the illegal acts of their sources. It also goes against press freedom precedents going back to the Pentagon Papers and contains arguments that could make it more difficult for reporters to do their jobs or that foreign governments could use against U.S. journalists working abroad, First Amendment experts told CPJ.

“I’m unhappy that there’s even an allegation that you could be held liable for publishing leaked information that you didn’t have anything to do with obtaining,” said George Freeman, a former lawyer for The New York Times and executive director of the independent advisory group, Media Law Resource Center. James Goodale, the First Amendment lawyer who defended The New York Times in the 1971 Pentagon Papers case, said that the suit appeared to be the first time WikiLeaks has been sued for a journalistic function. Goodale, a senior adviser to CPJ and former board chair, added that the DNC had “paid zero attention to the First Amendment ramifications of their suit.”

The DNC argues that WikiLeaks was involved in a conspiracy, rendering the normally protected act of publicizing documents tantamount to the criminal act of hacking the servers. Its suit contends that WikiLeaks and Assange violated laws that ban disseminating trade secrets and forbid wiretapping. To tie WikiLeaks and Assange to the underlying illegal act of hacking, the DNC cited the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a law originally intended to tie street-level criminals to gang leaders.

President Trump has denied that his campaign was involved in such a conspiracy, and Russian President Vladimir Putin denied the hackers acted on behalf of his government.

The case raises a number of important press freedom questions: Where should courts draw the line between source-building and “conspiring”? What activities could implicate a journalist in a source’s illegal behavior? Would putting a SecureDrop link soliciting leaks count as illegal conspiracy? And if a reporter asked for documents on an individual while indicating that they think the person deserves to be exposed, would that count as shared motive, or is the only truly protected activity passively receiving leaks, like radio host Vopper?

“There is a spectrum that run on one side from someone dropping a plain manila envelope, to the other extreme where you actually steal the documents yourself,” said David McCraw, deputy general counsel for The New York Times. “The line in the middle is still being determined by the courts.”

David Bralow, an attorney with The Intercept, added, “It’s hard to see many of WikiLeaks’ activities as being different than other news organizations’ actions when it receives important information, talks to sources and decides what to publish. The First Amendment protects all speakers, not simply a special class of speaker.”

The DNC lawsuit claims that Assange harbored animosity toward Clinton, was in touch with the Trump campaign, and timed the release of his documents to harm the Clinton campaign. But as McCraw said, a publisher “having a point of view,” doesn’t mean they aren’t engaged in “journalistic activity.” And coordinating publication time doesn’t necessarily establish an “agent-principal” relationship between the hackers who broke the law and the publishers.

Xochitl Hinojosa, a DNC spokesperson, told CPJ, “This lawsuit is about an illegal foreign intelligence operation against the United States by a hostile adversary that found active and willing partners in the Trump campaign, as well as WikiLeaks, which acted at the behest of the Russians.” Hinojosa added, “We will present these arguments further in court.”

WikiLeaks did not respond to CPJ’s emailed request for comment.

Marcy Wheeler, an independent national security reporter who has reviewed the DNC complaint, said the legal theory behind it could be applied to other leaks such as the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers–internal documents that were likely obtained illegally from law firms and financial institutions, and then passed to the press. Similar legal cases have already been brought in Europe. One of the law firms named in the Paradise Papers case sued the BBC and the Guardian, the BBC reported.

The DNC’s argument, Wheeler said, could be replicated by the Department of Justice to target an outlet like The Intercept. “If this precedent is out there, the government would happily describe The Intercept as a co-conspirator,” in the Winners or Albury leaks, she told CPJ, referring to former military contractor Reality Winners, and former FBI agent Terry Albury, whom several news outlets speculated were the sources for major leak investigations revealed by The Intercept.

The Department of Justice has also previously tried to implicate reporters in leak instigations, including in 2010, when it named Fox News reporter James Rosen in a search warrant as a “co-conspirator” and surveilled him.

This is why CPJ has long maintained that WikiLeaks and Assange should not be prosecuted under the Espionage Act for publishing classified documents procured by someone else. WikiLeaks, however, has not always been a responsible steward of its materials. In 2011, the organization released unredacted diplomatic cables that endangered the life of the Ethiopian reporter Argaw Ashine. And in general, WikiLeak’s practice of publicizing large data dumps without probing the context or motivations of leakers can render it vulnerable to manipulation, as CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon has written. Still, as CPJ wrote in a letter to the Obama administration in 2010, arresting Assange would set dangerous precedent for publishers everywhere.

Despite the challenges in dealing with large scale leaks from state hackers, it has become an increasingly routine practice. In the most recent, attorneys for Republican fundraiser Elliot Broidy filed a subpoena May 16 for documents from The Associated Press as part of a civil suit against the Qatar government, which he accuses of hacking his emails and leaking them to journalists at the AP and other news organizations. The AP told the Freedom of the Press Foundation that it intends to fight the subpoena. And the Qataris denied any role in the hack, The New York Times reported.

The U.S. government already uses vague terminology, which is potentially damaging to publishers, to describe WikiLeaks. Last year, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo–then CIA Director–labeled WikiLeaks a “non-state hostile intelligence service.” The language was also inserted into a Senate appropriations bill. Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon, who accused WikiLeaks of participating in an “attack” on American democracy, nonetheless raised alarms about the terminology. In a statement issued by his office last August, he said, “The use of the novel phrase ‘non-state hostile intelligence service’ may have legal, constitutional, and policy implications, particularly should it be applied to journalists inquiring about secrets.”

The notion that journalistic activity such as cultivating sources and receiving illegally obtained documents could be construed as part of a criminal conspiracy is, according to Goodale, the “greatest threat to press freedom today.” “It will inhibit reporters’ ability to get whistleblower information, because as soon as you talk to them in any aggressive fashion you could be guilty of a crime,” Goodale said.

The DNC goes a step further, Wheeler argued, by classifying its emails as “trade secrets,” and claiming that WikiLeaks and Assange broke federal laws specifically crafted to punish economic espionage. “If Forbes publishes information about what [a] business is doing that they got as a leaked document, given this precedent, the business could say that Forbes was engaged in economic espionage,” Wheeler said.

Jesse Eisinger, a reporter and editor with ProPublica, described leaked documents as the “lifeblood of all journalists,” and said that without them, “reporters would be severely crippled in our ability to do accountability journalism of any kind.” Eisinger is part of a joint ProPublica and WNYC team which is soliciting tips and crowdsourcing as part of its investigation into Trump’s business empire.

Aside from the legal implications, the complaint raises concerns over how the DNC views reporters. The DNC would not make available one of its attorneys to discuss the case or answer a series of detailed questions that CPJ provided via email. “Unlike Presidents Trump and Putin, the Democratic Party respects the First Amendment and cherishes the critical role that the free press plays in our democracy,” Hinojosa, the DNC spokesperson, said in a brief statement.

Some legal experts however, said the DNC is in danger of bending those principles. “I think that this civil suit goes well beyond what the First Amendment permits,” said Barry Pollack, the former president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, who represents Assange in criminal matters. “We have seen in DOJs under both parties, a willingness to at least bump right up against the line of pursuing journalists criminally. And that’s dangerous.”

Some journalists have defended the DNC suit as a way to bring greater transparency to the 2016 hacking scandal. Writing in the New Yorker, Jeffrey Toobin argued that if successful, the lawsuit could be a way to secure sworn interviews with “key players.”

WikiLeaks, for its part, appears eager to use the discovery phase to compel the release of DNC documents. The organization tweeted, “Discovery is going to be amazing fun,” in response to the lawsuit.

Many of the legal experts said they assume the counts that mention Assange and WikiLeaks will be dismissed when the judge assesses if the conspiracy claims in the DNC lawsuit are “plausible.” If the judge moves forward, University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck said, it will be because he finds a way to substantially differentiate what WikiLeaks does from routine reporting practices.

However, Charles Glasser, a professor at NYU’s journalism school who spent over a dozen years as global media counsel for Bloomberg, said that if the charges against Assange and WikiLeaks survived, it could pave the way for companies or others to label everyone–from those who illegally obtain documents to the press–as co-conspirators.

Lynn Oberlander, a lawyer for Gizmodo, added that foreign governments, political party, or corporations could use the DNC’s legal theory against American journalists abroad. If a U.S. funded outlet such as Voice of America or an American-owned private entity published illegally obtained documents from a foreign political party, influencing the outcome of a foreign election, the outlet and its reporters could be sued for conspiracy, Oberlander said. “If you start doing this here in the U.S., you have to wonder: does someone start doing this against American interests abroad?”

[EDITOR’S NOTE: This post has been updated in the second paragraph to correct the spelling of Bartnicki and the 22nd paragraph to correct the name of the organization of which Barry Pollack is the former president.]