Corruption is one of the most dangerous beats for journalists, and one of the most important for holding those in power to account. There is growing international recognition that corruption is also one of the biggest impediments to poverty reduction and good governance. This is why journalists on this beat must be protected, including by multilateral lending institutions such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, which just concluded their annual meetings in Washington D.C.

At a civil society forum on the sidelines of the meetings last week, World Bank President Jim Young Kim and IMF President Christine Lagarde, leaders of two of the world’s most important lenders to poor countries, cited concern over corruption and the damaging impact that tax evasion has on poverty alleviation. But with recipient countries often ranking among the more corrupt and least accountable, the issue of who pays taxes and where the money goes is often buried in secrecy.

In Pakistan, a major recipient of investment lending from the World Bank, journalist and winner of CPJ’s 2011 International Press Freedom Award, Umar Cheema, was kidnapped and brutally attacked after writing critical articles about corruption in Pakistan. But he refused to be deterred and went on to launch an investigative reporting center dedicated to tax analysis in a country where few political appointees pay taxes.

“Particularly in repressive societies, or places run by oligarchs and overlords, journalists risk both their freedom and their safety simply by reporting on corruption and conflicts of interest,” David Kaplan, executive director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, an association of more than 138 member organizations in 62 countries, said in an interview. “Yet I can think of no graver issue faced by our members than corruption. It comes up in every issue we report on — the economy, crime, health care, education, the environment.”

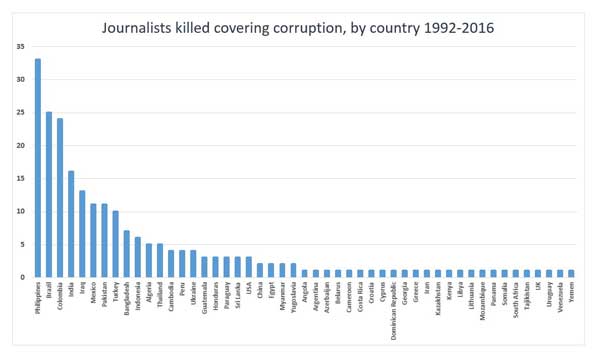

According to CPJ research, at least 20 percent of the more than 1200 journalists killed in the line of duty since 1992 covered corruption. Of the 246 journalists killed during this time who were working on corruption, 95 percent were murdered. In just 13 cases was full justice achieved, meaning that all involved in the murder were convicted.

Nearly all of the murder victims were local journalists attempting to report on corruption in their own countries. “Those targeting the press are trying to shut people up, and not create a bigger firestorm,” said Sasha Chavkin, a reporter at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists who worked on a collaborative investigation into displacement caused by World Bank projects.

Corruption is costly, equivalent to more than 5 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) with more than $1 trillion paid in bribes per year, according to the World Economic Forum. The cost is even higher in Africa, which receives a significant portion of development aid, and where the World Bank estimated in 2007 that 25 percent of GDP was lost to corruption each year.

In light of the acknowledgement that good governance cannot be separated from development goals like poverty reduction and economic growth, the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted last year include one related to reducing corruption and bribery as well as ensuring public access to information and protecting fundamental freedoms.

Multilateral organizations have at times required recipient countries to adopt freedom of information (FOI) laws as a condition for joining or receiving financing. China and Pakistan, for example, were granted membership in the World Trade Organization (WTO) and an IMF aid package respectively on the condition they adopt FOI provisions, according to The Associated Press.

But the existence of a law is not the same as its implementation. In 2011, the AP tested the freedom of information laws in 105 countries and found that less than half responded and among those, just a handful responded fully and within their own deadlines. That is why it is imperative that the SDGs do more than assess the existence of such a law.

Among journalists who have faced retaliation and threats for reporting on corruption in projects funded by organizations such as the World Bank, IMF, the U.N. Development Fund, and the U.S. Millennium Challenge Corporation are publisher Joseph Titi of the Ivory Coast. Titi was jailed for a week and charged in 2015 with a litany of offenses following the publication of an article alleging money laundering and embezzlement from the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative of the IMF and World Bank, CPJ reported at the time.

The imprisonment and murder of journalists is the tip of the iceberg. Harassment and intimidation, legal statutes like criminal defamation and prohibitions again publishing false news, and confiscation or closure of offending outlets are also common.

An editor in Hong Kong was viciously attacked and dismissed from his job after his newspaper exposed offshore holdings of China’s political elite, while a journalist in India was brutally attacked and set on fire after reporting allegations of land grabs and rape by a local minister.

Below the visibility of such retaliation, self-censorship spreads.

Carmen Aristegui, a popular morning TV anchor in Mexico, was fired after the broadcaster MVS was put under pressure by the government over her investigative reporting, including on government infrastructure projects, according to the anchor. The station owner then sued her for moral damages, she said. She warned CPJ at the time that cases like this were likely “to impose self-censorship on journalists.”

“[A] free press is essential to checking abuse of executive power,” according to a working paper by BBC Media Action’s James Deane. “Support to independent media, both financially and economically, has been a low priority in recent years [for donors].”

Yet the return on investment in independent investigative media could be significant. The Sarajevo-based Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), for example, received just $5 million in governmental funding and through its reporting enabled law enforcement and tax agencies to seize more than $2.8 billion of assets and fines, a return of 56,000 percent, according to GIJN.

It is time for the U.N., the World Bank, the IMF and other lending organizations to stand together to protect journalists, even if only to protect their own bottom line.