Highly publicized murders of journalists heighten awareness of the grave dangers that reporters and photographers face around the world. Less widely known are the myriad other risks to journalists, including imprisonment, cyberattacks, harassment, frivolous lawsuits, and censorship. These threats exist to varying degrees in war zones, politically volatile regions, and even stable countries, and they all hold the potential to limit public access to news. The risks are increasing due to widespread unrest and in response to the broad dissemination of critical information through social media and the Internet.

Attacks on the Press2015 Edition

Going it alone: More freelancers means less support, greater danger

The lack of adequate preparation might make safety experts shudder, but faced with low pay and high risk, the only option for many conflict journalists is to learn on the fly.

Broadcasting murder: Militants use media for deadly purpose

Islamic State, Boko Haram, and Mexican drug cartels videotape their own violence, presenting a conundrum for the press.

Covering war for the first time—in Syria

Lacking the support of an editor or established news organization, a young freelancer turned to a community of independent journalists who helped her find her way in a conflict zone.

The rules of conflict reporting are changing

Syria has reshaped the way war is covered. Faced with continuing journalist kidnappings and murders, one veteran reporter proposes a new approach.

Lack of media coverage compounds the violence in Libya

The world hardly knows what’s happening in Libya. The information vacuum allows various groups to distort the truth and even to cause greater bloodshed.

Reporting, with bodyguards, on the Paraguayan border

Amid lawlessness in Paraguay, one journalist has his own security detail to fend off attacks by smugglers and the henchmen of corrupt politicians.

Between conflict and stability: Journalists in Mexico and Pakistan cope with everyday threats

Working where violence is endemic takes a psychological toll on journalists and their families, and hampers the ability to report.

Treating the Internet as the enemy in the Middle East

When it comes to popular movements, no one knows better than Middle East leaders how powerful the Internet can be—and no one is doing more to undermine it.

Conflating terrorism and journalism in Ethiopia

Addis Ababa is using defense against terrorism to justify stifling the press and putting reporters in jail.

Surveillance forces journalists to think and act like spies

Only with expertise, practice, and expensive tools can the media protect sources in the digital age. Journalists now compete with spooks, and the spooks have the home-field advantage.

Overzealous British media prompt overzealous backlash

Journalists in the U.K. are besieged by police, Parliament, pressure groups, public relations agents, and even publishers.

Finding new ways to censor journalists in Turkey

The declining number of imprisoned journalists is a welcome change, but it does not indicate a more open approach toward the media in Turkey.

We completely agree: Egyptian media in the era of President el-Sisi

Self-censorship, firings, and official harassment are transforming many Egyptian journalists into mouthpieces for the government.

Two continents, two courts, two approaches to privacy

As the United States confirms its value of free speech over privacy, Europe tilts in the opposite direction.

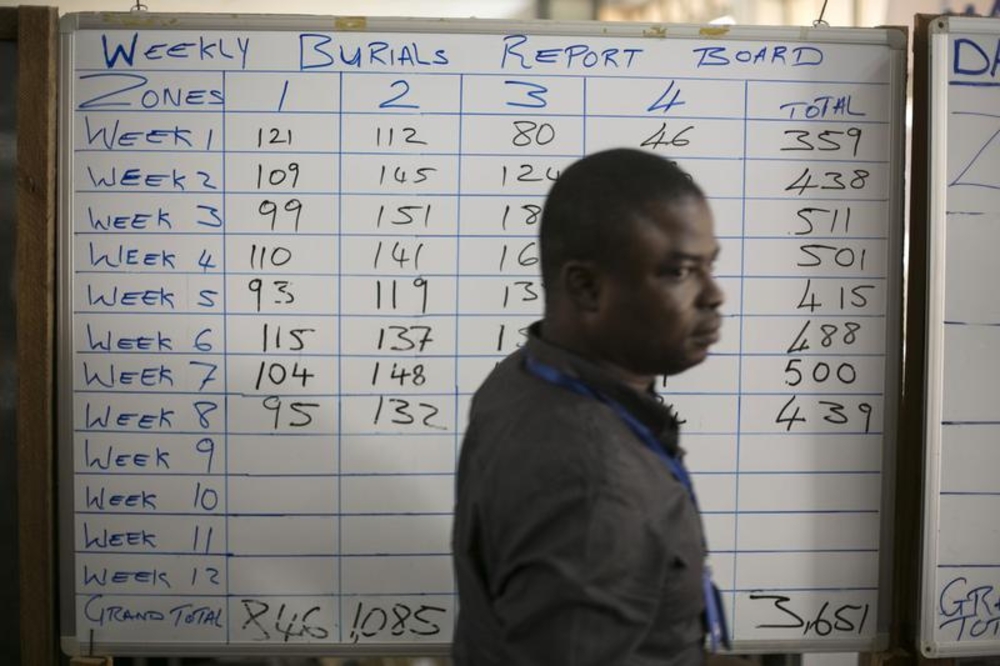

Amid Ebola outbreak, West African governments try to isolate media

In an environment where access to facts can be life-saving, some West African governments appear as interested in arresting reporters as arresting a deadly disease.

Outdated secrecy laws stifle the press in South Africa

The invocation of antiquated laws and the introduction of restrictive new ones set a dangerous precedent for censorship in a country still finding its way as a democracy.

Journalists grapple with increasing power of European extremists

The rise of right-wing groups across the continent leads to attacks on journalists—and a fierce debate in the profession over how to report on nationalist political parties.

Indian businesses exert financial muscle to control the press

Corporate interests try to suppress unfavorable coverage through expensive lawsuits, the withholding of advertising, and the outright purchase of news outlets.

For clues to censorship in Hong Kong, look to Singapore, not Beijing

Many in Hong Kong fear China’s blunt media restrictions, but the territory’s journalists are more likely to encounter the more subtle weapons of Singapore.

The death of glasnost: How Russia’s attempt at openness failed

There was a moment when the Russian media was poised to join the West’s in open and objective news coverage. That moment has passed.

Journalists overcome obstacles with crowdfunding and determination

Declining revenue poses one of the greatest challenges to today’s media. Yet many journalists are scraping by with help from new platforms and their own ingenuity.

Media wars create information vacuum in Ukraine

The shutdown of broadcasters, restrictions on reporting, blatant propaganda, and beatings, abductions, and killings of journalists leave people in eastern Ukraine and Crimea in the dark.