International Institutions Fail To Defend Press Freedom

by Joel Simon

UNESCO is the primary entity within the United Nations dedicated to the defense of press freedom. Yet in 2010, journalism and human rights organizations were forced to launch an international campaign to stop UNESCO from presenting a prize honoring one of Africa’s most notorious press freedom abusers.

ATTACKS ON

THE PRESS: 2010

• Main Index

Worldwide

• International

Institutions Fail to

Defend Press Freedom

• Exposing the Internet’s

Shadowy Assailants

Africa

• Across Continent,

Governments Criminalize

Investigative Reporting

Americas

• In Latin America, a

Return of Censorship

Asia

• Partisan Journalism and

the Cycle of Repression

Europe and

Central Asia

• On the Runet, Old-School

Repression Meets New

Middle East

and North Africa

• Suppression Under the

Cover of National Security

In 2008, UNESCO accepted a $3 million donation from President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea to underwrite an annual prize in life sciences. For more than three decades, Obiang has ruled the tiny West African nation with an iron hand. Although an oil boom has given Equatorial Guinea one of the highest per-capita incomes in Africa, massive corruption and mismanagement have reduced the country’s standard of living to one of the lowest on the continent. Journalists in Equatorial Guinea face systematic harassment, censorship, and detention. CPJ named Equatorial Guinea one of the world’s 10 most censored countries in a 2006 survey.

International human rights and press freedom organizations were outraged by plans for an Obiang prize. CPJ joined a coalition to fight against it and rallied opposition from international press freedom organizations and prominent journalists, including winners of UNESCO’s own Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize. Plans for an Obiang prize were finally defeated in October when UNESCO’s executive board said it would not go forward without the consensus of its members, which will not be reached given the strong opposition expressed by several of them.

This was a victory, but the battle should never have been fought. The fact is that many international governmental organizations created to defend press freedom are consistently failing to fulfill their mission. As with the Obiang controversy, human rights and press freedom groups are expending time, resources, and energy ensuring these institutions do not veer widely from their mandate.

Take the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, or OSCE. The 56-member intergovernmental organization, created during the Cold War to track security conditions in Europe, is charged with the defense of press freedom and human rights. Yet in 2007, Kazakhstan, one of the region’s worst press freedom violators, was elected chairman of the organi-zation. The country’s chairmanship was delayed for a year so Astana could implement promised press freedom reforms, including amending its repressive laws. Kazakhstan not only failed to fulfill its promises, it introduced restrictive new measures–yet it still assumed OSCE leadership in 2010 without hindrance.

A CPJ report released in September found that attacks on Kazakh journalists continued before and during the country’s OSCE chairmanship. A journalist and a prominent human rights activist were jailed under abysmal conditions. Two critical newspapers were shuttered. A highly restrictive Internet law was passed, crippling development of a critical blogosphere. Under a broadly worded privacy law enacted just as Kazakhstan assumed OSCE leadership, journalists can be jailed for up to five years for reporting on “an individual’s life.” As the CPJ report noted, “By disregarding human rights and press freedom at home, Kazakhstan compromised the organization’s international reputation as a guardian of these rights, undermined the OSCE’s relevance and effectiveness, and thus devalued human rights in all OSCE states.”

In October, a CPJ delegation traveled to OSCE headquarters in Vienna to urge organization officials to address Kazakhstan’s poor press freedom record at a summit set for late year. In presenting its findings, CPJ noted that OSCE nations had agreed in the Moscow Commitment of 1991 that human rights and fundamental freedoms are a collective concern, not simply an individual state’s internal affair. When the summit was held, however, press freedom and human rights went unaddressed.

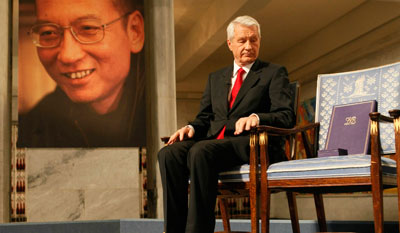

CPJ and other press freedom organizations have sought to enlist U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon in the global fight against impunity in journalist murders. In April 2007, a CPJ delegation met with Ban, who expressed admiration for journalists and pledged to back U.N. efforts to support their work. Over the next several years, Ban made a number of supportive statements, but his approach has been far from consistent. The secretary-general squandered a critical opportunity to defend press freedom when he failed to congratulate Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, the jailed human rights activist and journalist. As the Chinese government launched a global campaign against the award, Ban apparently succumbed to pressure and set a disappointing example for the entire U.N. system.

Intergovernmental organizations often consist of a political structure of member states and a legal structure that adjudicates the applicability of international treaties that protect human rights and press freedom. These legal structures are served, in turn, by special rapporteurs for freedom of expression, whose role is to advocate within the institutions and ensure press freedom mandates are upheld.

In many instances, these special rapporteurs have performed with distinction. U.N. Special Rapporteur Frank LaRue and Catalina Botero, special rapporteur for freedom of expression for the Organization of American States (OAS), have criticized and drawn attention to press freedom abuses. A joint mission by LaRue and Botero to Mexico in August attracted widespread attention to rampant anti-press violence there.

Some regional legal bodies also have positive records. The European Court of Human Rights, for example, has issued a number of significant rulings in press freedom cases from Russia and Azerbaijan. In an important 2010 decision in the case of Sanoma Uitgevers B.V. v. the Netherlands, the court put strict limits on the ability of governments to search newsrooms. CPJ signed on to an amicus brief in that case.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has ordered member states to provide direct protection to at-risk journalists, and it has provided effective mediation when the rights of journalists have been violated. Over the years, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has issued key decisions supporting press freedom, including a landmark ruling that struck down a criminal defamation conviction in Costa Rica.

These systems, however, break down at the political level. The OAS, which has been paralyzed by ideological battles in Latin America, rarely speaks out on press freedom violations. As press freedom is being legislated out of existence in Venezuela, OAS Secretary General José Miguel Insulza has failed to confront the government of President Hugo Chávez Frías. And when Azerbaijan failed to comply with a European Court order to release editor Eynulla Fatullayev–a 2009 CPJ International Press Freedom Awardee imprisoned on fabricated charges–the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers, the body tasked with ensuring compliance with court rulings, issued only a cautious reprimand to Baku. It did not adopt a resolution for sanctions against Azerbaijan as penalty for non-compliance, despite its mandate to do so. Azerbaijan shrugged off the rebuke and continued to hold Fatullayev.

Meanwhile, journalists under fire in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa expect no support from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the Arab League, or the African Union (AU). The AU is based in the capital of one of Africa’s worst press freedom abusers, Ethiopia, and the organization’s human rights body is based in the Gambia, a country where journalists are jailed, murdered, and disappeared. Despite the existence of a special rapporteur for free expression, the AU has been largely silent in the face of major press freedom violations in these countries.

Intergovernmental organizations are made of governments, of course, so the resistance of powerful international actors poses a challenge. China’s bullying efforts to suppress participation in the Nobel ceremony in Oslo illustrates its willingness to exert power to limit the influence of both international organizations and national governments that speak out for press freedom. China and Cuba have reacted aggressively when UNESCO has honored journalists from their countries with the Guillermo Cano prize.

The European Union, while espousing support for press freedom, is often unwilling to take a confrontational role. In the debate over the Obiang prize within UNESCO, for example, the EU seemed to modulate its opposition to avoid antagonizing African countries that supported the award. While the EU took steps to isolate Cuba after the 2003 crackdown on dissidents and the press, it was Spain working with the Catholic Church that negotiated the detainees’ release. Seventeen jailed Cuban journalists were released in 2010, although four remained in prison in late year.

The influence of the United States, which has traditionally defended press freedom within international organizations, has been diminished. There are many reasons for this, ranging from the reduced influence of U.S. media in the global arena to the lingering resentment in many parts of the world over U.S. human rights abuses, including the use of torture. The response of U.S. government officials to the release of classified documents by the anti-secrecy organization WikiLeaks has further complicated the issue.

In one telling example, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton met on the sidelines of the OSCE summit with Raushan Yesergepova, wife of a Kazakh editor jailed for divulging state secrets. He had published government memos showing the security service was exerting undue influence in a local tax case. The U.S. support was blunted, however. When a reporter at the summit asked about WikiLeaks’ release of classified State Department cables, Clinton condemned it as an illegal breach of security. Later, as Yesergepova relayed to us, a senior Kazakh official scolded the editor’s wife: “Didn’t you hear what Clinton just said? State secrets must never be revealed. It’s dangerous and wrong to do so.”

Today’s sad reality is that while international law guarantees the right to free expression, journalists can rely on few international institutions to defend that right. While nongovernmental organizations have filled the void by challenging press freedom abusers and raising concerns internationally, these groups are spending an increasing amount of time monitoring the behavior of international governmental organizations that should be their allies in the press freedom struggle.

It is not acceptable to shunt all responsibility for protection of press freedom to special rapporteurs, who are often politically isolated and underfunded. The political leaders of every international institution–from the United Nations to the AU, the OAS to the Council of Europe and the OSCE–need to speak out forcefully for press freedom and push back against member states who seek to block them from fulfilling this responsibility. They also need to work aggressively to enforce legal rulings. Journalists working in dangerous conditions feel isolated and abandoned by the very international institutions created to protect their rights. As this book documents, 145 journalists were jailed and 44 journalists were killed worldwide in 2010. Each of these violations represents an opportunity for international institutions to demand justice.

Joel Simon is executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists.