By Arlene Getz/CPJ Editorial Director

The persistent lack of justice for murdered reporters is a major threat to press freedom. Ten years after the United Nations declared an international day to end impunity for crimes against journalists – and more than 30 years after CPJ began documenting these killings – almost 80% of their killings remain unsolved. A CPJ report.

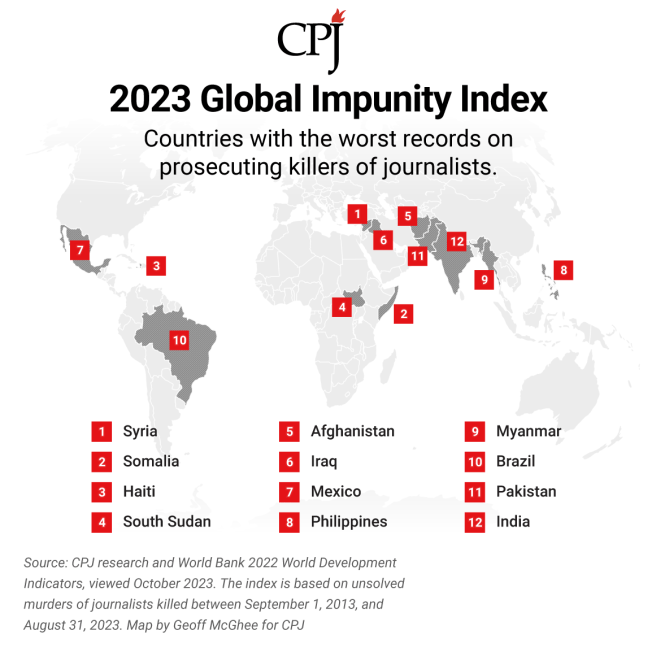

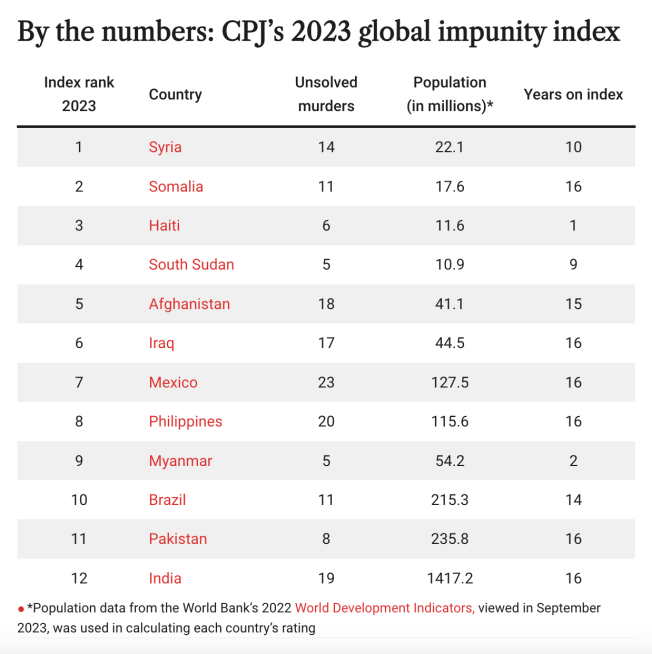

Crisis-hit Haiti has emerged as one of the countries where murderers of journalists are most likely to go free, the Committee to Protect Journalists’ 2023 Global Impunity Index has found. A devastating combination of gang violence, chronic poverty, political instability, and a dysfunctional judiciary are behind the Caribbean country’s first inclusion on CPJ’s annual list of nations where killers get away with murder.

Haiti now ranks as the world’s third-worst impunity offender, behind Syria and Somalia respectively. Somalia, along with Iraq, Mexico, the Philippines, Pakistan, and India, have been on the index every year since its inception. Syria, South Sudan, Afghanistan, and Brazil also have been there for years – a sobering reminder of the persistent and pernicious nature of impunity.

The reasons for these countries’ failure to prosecute journalists’ killers range from conflict to corruption, insurgency to inadequate law enforcement, and lack of political interest in punishing those willing to kill independent journalists. These states include democracies and autocracies, nations in turmoil and those with stable governments. Some are emerging from years of war, but a slowdown of hostilities has not ended their persecution of journalists. And as impunity becomes entrenched, it signals an indifference likely to embolden future killers and shrink independent reporting as alarmed journalists either flee their countries, dial back on their reporting, or leave the profession entirely.

This year’s index documents 261 journalists murdered in connection with their work between September 1, 2013 – the year the United Nations declared November 2 as the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists – and August 31, 2023. It finds that during this 10-year period, no-one has been held to account in 204 – more than 78% – of these cases.

Available in:

(Journalists killed in the Israel-Hamas war that began on October 7 are not included here because their deaths fall outside of the 10-year index period.)

A 78% impunity rate is a slight improvement on the 90% rate CPJ recorded a decade ago. But it should not be seen as reason for optimism. Impunity remains rampant and the stark reality is that nearly four out of every five killers of journalists are still getting away with murder.

Overall, CPJ has recorded the murders of 956 journalists in connection with their work since it began tracking them in 1992. A total of 757 – more than 79%– have gone wholly unprosecuted.

CPJ’s impunity index includes countries with at least five unsolved murders during a 10-year span. Only cases involving full impunity are listed; those where some have been convicted, but other suspects remain free – partial impunity – are not. Each country’s ranking is calculated as a proportion of their population size, meaning more populous countries like Mexico and India are lower on the list, in spite of having a higher number of journalist murders.

But the pernicious effects of impunity extend beyond the countries that have become fixtures on CPJ’s annual index. Unpunished murders have an intimidating effect on local journalists everywhere, corroding press freedom and shrinking public-interest reporting.

Beyond the index

Global Impunity Index 2023 Table of contents

In the Israeli-occupied West Bank, Palestinian journalists interviewed by CPJ for the “Deadly Pattern” report published earlier this year said their coverage had been undermined by escalating fears for their safety after the Israel Defense Forces fatally shot Al-Jazeera Arabic correspondent Shireen Abu Akleh in May 2022. CPJ’s investigation found that no-one had been held accountable for the deaths of 20 journalists by Israeli military fire in 22 years. “The impunity in these cases has severely undermined the freedom of the press, leaving the rights of journalists in precarity,” noted the report. (Israel is not listed in the impunity index because fewer than five journalists killed during the index period are classified as having been targeted for murder.)

In several countries in the European Union, typically considered the safest places for journalists, press freedom has come under increasing pressure, with journalist murders remaining unsolved in Malta, Slovakia, Greece, and the Netherlands.

In Malta and Slovakia, full justice in the killings of Daphne Caruana Galizia and Ján Kuciak is yet to be achieved. Greece has yet to hold anyone accountable for the 2010 killing of Sokratis Giolias, with a recent report by “ A Safer World for the Truth” – a collaboration of rights groups that includes CPJ – finding gaps in authorities’ investigations into the murder of Giolias and the similar killing of Giorgos Karaivaz 11 years later.

The stark reality is that nearly four out of every five killers of journalists are still getting away with murder.

In the Netherlands, nine suspects are awaiting trial for the fatal shooting of Dutch reporter Peter R. de Vries as he left a TV studio in 2021. While it remains unclear whether De Vries and Karaivaz were targeted because of their work, colleagues in Greece and Holland have told CPJ their deaths have left lingering insecurity and self-censorship in the media community. De Vries’ death had “a chilling effect on journalists,” Dutch crime reporter Paul Vugts – the Netherlands’ first journalist to receive full police protection because of work-related death threats – told CPJ.

In countries considered less safe for journalists, violent retaliation for their coverage also continues.

In the central African nation of Cameroon, the mutilated corpse of journalist Martinez Zogo was found on January 22, 2023. At least one other journalist with ties to Zogo, Jean-Jacques Ola Bebe, was found dead 12 days later. Several journalists warned by Zogo that they too were on a hit list have fled the country; others opted for self-censorship. “The killing, physical attacks, abduction, torture, and harassment of journalists by Cameroonian police, intelligence agencies, military, and non-state actors continue to have a severe chilling effect [on the media],” noted a July report submitted to the United Nations by a group that included CPJ.

Hard path to justice

Since 1992, full justice has only been achieved for 47 murdered journalists – fewer than 5%. CPJ’s data shows that factors like international pressure, universal jurisdiction, and changes in government can play instrumental roles in securing that punishment.

One landmark case: Peruvian journalist Hugo Bustíos Saavedra. Bustios was killed in an army ambush on November 24, 1988, while covering the conflict between government forces and Shining Path guerrillas. It took almost 35 years for a Peruvian criminal court to sentence Daniel Urresti Elera, then the army’s intelligence chief in the zone where Bustios was killed, to 12 years in prison for his part in the killing. (Explore a timeline of the Bustios case here.)

Urresti’s conviction resulted from a combination of changing internal politics in Peruvian leadership, the re-opening of investigations into human rights cases after Peru’s Supreme Court effectively struck down the 1995 amnesty law protecting military officers, and ongoing advocacy by rights groups – including CPJ – at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

In the Central African Republic, the August death of Yevgeny Prigozhin, the leader of the Russian private mercenary group killed in a plane crash two months after ordering his troops to march on Moscow, has led to hopes that those with information about the 2018 murders of three Russian journalists might come forward, writes CPJ’s Europe and Central Asia Program Coordinator Gulnoza Said. The journalists, Orkhan Dzhemal, Kirill Radchenko and Aleksandr Rastorguyev, were shot dead three days after arriving in the country to investigate Wagner’s activities there.

Unpunished murders have an intimidating effect on local journalists everywhere, corroding press freedom and shrinking public-interest reporting.

Universal jurisdiction, which allows a country to prosecute crimes against humanity regardless of where they were committed, can also be an effective tool. Bai Lowe, accused of being a member of the “Junglers” death squad that killed Gambian journalist Deyda Hydara, is on trial in Germany – the first person accused of human rights violations during the dictatorship of Yahya Jammeh to be tried outside Gambia.

International pressure is another factor that may prompt authorities to investigate unsolved killers – even if the probes don’t necessarily lead to prosecution. CPJ’s “Deadly Pattern report about journalists killed by the Israeli military found that authorities were more likely to investigate killings of journalists with foreign passports. “The degree to which Israel investigates, or claims to investigate, journalist killings appears to be related to external pressure,” noted the report.

The Bustios case may have offered a glimmer of hope. But it also underscores that the road to justice can be long and tortuous – and for the vast majority of murdered journalists, it never comes at all.

More about countries on the index

1) Syria

Fourteen journalists were murdered with full impunity in Syria during the 2023 index period. Ten died between 2013 and 2016, as the initial uprising against the Bashar al-Assad regime widened into a full-scale war involving regional and global powers and the militant Islamic State (IS) began seizing control of Syrian territory. IS is believed to have murdered eight of the 10 killed between 2013 and 2016. Fighting has eased since Assad regained control of most of the country, but Syrian media have been dealt a hard blow as numerous journalists fled into exile and military authorities continue to harass, threaten or detain journalists.

2) Somalia

The worst offender on the index for the last eight years, Somalia dropped below Syria in the 2023 index. This drop to second does not signal an improvement in Somalia’s impunity record, but instead arises from the method used to calculate the rankings: Three of the four journalists murdered in 2013 were killed before September 1 of that year, meaning they fall outside of this year’s index period. Most of the 11 journalists during the index period died between 2013 and 2018, believed to have been killed by Al-Shabaab, an insurgent group which seeks to establish an Islamic state in Somalia. Somalia remains unstable amid a renewed offensive against Al-Shabaab. Covering the insurgent group remains a dangerous, even deadly, assignment. The media are severely hampered in their reporting as journalists continue to face arrests, threats, and harassment.

3) Haiti

Haiti’s entry into the index follows the unsolved murders of six journalists since 2019. Five were killed in 2022 and 2023, among the hundreds of Haitians killed by the criminal gangs that have taken over large parts of Haiti as the country struggles to deal with an economic crisis aggravated by a series of natural disasters and the political void following the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse. Haitian journalists have also been kidnapped and forced to flee their homes amid fears that their work put them at greater risk than other civilians. (Read more about conditions in Haiti here.)

4) South Sudan

The five journalists murdered in South Sudan all died when unidentified gunmen ambushed an official convoy in Western Bahr al Ghazal state on January 25, 2015. South Sudan’s media have long been under pressure in a country plagued by civil war and human rights violations since gaining independence in 2011. CPJ has documented numerous instances of harassment, detention, jailing and the death of a war reporter in crossfire in recent years.

5) Afghanistan

The militant Islamic State has claimed responsibility for killing 13 of the 18 journalists murdered in Afghanistan in the last decade. Ten died in 2018 alone, nine of them in a double suicide bomb attack in Kabul on April 30 that year, and one shot dead the previous week in Kandahar. While the deadly targeting of reporters appears to have slowed since the Taliban returned to office in 2021, large numbers of journalists have fled the country and the group’s escalating repression forced has gutted the country’s once-vibrant media landscape.

6) Iraq

CPJ has not documented any journalists murdered for their work in Iraq since 2017. Fourteen of the 17 listed in CPJ’s database were killed in 2013 and 2015 amid a resurgence of sectarian violence. While the violence has eased, media restrictions and threats against journalists – especially in Iraqi Kurdistan – continue.

7) Mexico

Killings of journalists in Mexico have dropped from last year’s high, but the country remains one of the world’s most dangerous for journalists. Seventeen of the 23 journalists murdered during the index period are believed to have been killed by criminal fire. CPJ has found that the high levels of violence against journalists can be attributed in part to the failure of state and federal authorities to make the environment safer for reporters or even take crimes against the press seriously.

8) Philippines

The Philippines remains a dangerous place to work as a reporter, especially for radio journalists. While Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has adopted a more conciliatory approach toward the media since becoming president in June 2022, CPJ reported that a culture of self-censorship persists and Marcos’ change in tone has not yet been accompanied by substantive actions to undo the damage wrought to press freedom under the Rodrigo Duterte administration. Twenty journalists have been murdered in the Philippines since September 2013; three since Marcos took office.

9) Myanmar

The number of journalists murdered with impunity in Myanmar remains at five, with no new cases documented this year. The country was listed for the first time in 2022, the same year the country’s military junta jailed dozens of journalists and used broad anti-state laws to quash independent reporting in the wake of its coup in February 2021.

10) Brazil

Brazil is working to reestablish good relations with the media following Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s defeat of far-right President Jair Bolsonaro in 2022, with the government introducing measures like an Observatory on Violence Against Journalists earlier this year. Brazil did not record any new journalist murders in 2023, but the killers – mostly believed to be criminal groups – of 11 journalists murdered in Brazil during the index period remain at large. The 2022 murders of British journalist Dom Phillips and Indigenous issues expert Bruno Pereira in the Amazon continue to underscore the dangers faced by environmental reporters in the region.

11) Pakistan

Pakistan, one of the countries that has appeared on the index every year since its inception, recorded eight journalists killed with impunity during this year’s index period. Four are believed to have been killed by criminals, two by political groups. CPJ has documented numerous press freedom violations in the country following the ouster of former Prime Minister Imran Khan in April 2022.

12) India

India too has appeared on CPJ’s impunity index every year since 2008. The majority of the 19 murdered since September 2013 are believed to have been killed by criminals over reporting on topics ranging from environmental issues to local politics, but journalists are facing increasing pressure ahead of the country’s 2024 election. In addition to detentions, police raids and blocks of news websites, authorities are using a counterterrorism law against the media.

Arlene Getz is editorial director of the Committee to Protect Journalists. Now based in New York, she has worked in Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East as a foreign correspondent, editor, and editorial executive for Reuters, CNN, and Newsweek. Follow her on LinkedIn.

Methodology

CPJ’s Global Impunity Index calculates the number of unsolved journalist murders as a percentage of each country’s population. For this index, CPJ examined journalist murders that occurred between September 1, 2013, and August 31, 2023, and remain unsolved. Only those nations with five or more unsolved cases are included on the index. CPJ defines murder as the targeted killing of a journalist, whether premeditated or spontaneous, in direct reprisal for the journalist’s work. This index does not include cases of journalists killed in combat zones or while on dangerous assignments, such as coverage of protests that turn violent. Cases are considered unsolved when no convictions have been obtained, even if suspects have been identified and are in custody. Cases in which some but not all suspects have been convicted are classified as partial impunity. Cases in which the suspected perpetrators were killed during apprehension also are categorized as partial impunity. The index only tallies murders that have been carried out with complete impunity. It does not include those for which partial justice has been achieved. Population data from the World Bank’s 2022 World Development Indicators, viewed in October 2023, were used in calculating each country’s rating.