Iraqi Kurdistan may seem calm compared with much of the Middle East, but the media are vulnerable whenever internal political tensions flare. Amid impunity for anti-press attacks, including murder and arson, journalists say they must self-censor on topics like religion, social inequality, and corruption associated with powerful officials. A CPJ special report by Namo Abdulla

Published April 22, 2014

SULAYMANIYAH

“You son of a dog, if you publish that magazine tomorrow, I’ll entomb your head in your dog father’s grave.”

The magazine was Rayel, an independent monthly publication in Kurdistan.

More in this report

• CPJ's recommendations

In other languages

• العربية

• کوردی (PDF)

In print

• English

The “son of a dog” was 32-year-old Rayel editor-in-chief Kawa Garmyane, who had published several reports alleging corruption among Kurdish politicians, particularly those in the powerful political party, Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK).

The speaker, according to a recording of the phone conversation published on YouTube in July 2012, was Mahmoud Sangawi, a member of the PUK and an army general.

Eighteen months later, Garmyane was dead, shot outside his home in Kalar, south of the city of Sulaymaniyah, on December 5, 2013.

According to news reports, Sangawi was the prime suspect. He was arrested for the murder in January 2014, but quickly released on lack of evidence. He maintains his innocence. A rank-and-file member of the PUK has been arrested and pleaded guilty to the murder, but Garmanye’s family says it is impossible for an average citizen to have carried out the attack singlehandedly and that the real criminal or the mastermind is still at large.

Sangawi has not denied the authenticity of the “son of a dog” phone call, in which he used vulgar language to threaten Garmyane, because, in his own words, the magazine had published a critical article and picture of him in an earlier edition.

Immediately after the killing, some journalists and human rights defenders expressed doubt that Garmyane’s murder would be solved and the mastermind brought to justice. On December 20, 2013, protesters across Kurdistan carried banners saying, “Not only the killer. Who’s behind the killer?” and “We all know who the killer is.”

Celebrated Kurdish poet Abdulla Pashew published a statement harshly criticizing the Kurdish Regional Government. “Kawa [Garmyane] was martyred in a country where there are no system of governance, no institutions, no courts, no constitution, and no laws. That is why we should not expect the trial of the real criminals.”

“High-ranking PUK officials did this,” shouted a crying Shireen Amin, the wife of Garmyane, to a crowd of journalists and other Kurds gathered in front of his home in December 2013. “I beg all of you, members of the media, to not accept this injustice. Kawa was also a brother to you.” She gave birth to their first child only 17 days after her husband’s death.

Lack of law enforcement breeds self-censorship

Iraqi Kurdistan, with a population of around 5 million, straddles three major Iraqi provinces—Erbil, Duhok, and Sulaymaniyah—and borders Iran, Turkey, and Syria. The territory boasts its own flag and national anthem, and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) enjoys near-total control over the territory’s internal and foreign affairs. Ruling power has been shared by the PUK and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) since 2003, although recently a third party, Gorran (Change), has made waves by attracting significant votes.

While much of post-war Iraq was ravaged by car bombs, suicide attacks, and religious extremism, Kurdistan largely escaped such violence. The economy is booming, thanks largely to huge oil and natural gas reserves. However, below a surface that appears calm when compared with much of the Middle East, political tensions sometimes run high, and this is when the media are most vulnerable. Local journalists say Kurdistan is rife with nepotism and corruption; many Kurds accuse their leaders of using oil money to enrich themselves instead of building a vibrant democracy and economy for all. In smaller cities, such as Kalar and Halabja, people complain about a lack of basic services, such as paved roads, jobs, and electricity.

Garmyane’s murder was the most recent high-profile attack on a journalist in the Kurdish territory, but it was not an isolated case. Over the past few years, the nonprofit advocacy group Metro Center to Defend Journalists, based in Sulaymaniyah, has recorded in detail nearly 700 attacks on journalists, including threats, harassment, beatings, detentions, intimidation, and arson. Most of the attacks have gone unpunished.

The number of attacks peaked in 2011, when thousands of Kurds inspired by the Arab Spring took to the streets in a months-long protest against the rule of what they viewed as authoritarian and corrupt leadership. In the ensuing clashes, 10 people, including two security forces, were killed, according to hospital and government officials. At least four journalists were shot and wounded. That year, the Metro Center documented an unprecedented 359 attacks on journalists and media organizations.

In 2012 and 2013, the number of attacks documented by the Metro Center was significantly lower, at 132 and 193, respectively.

Government officials claim that the decline in attacks is indicative of more deeply rooted democracy and increased tolerance for dissent. Jalal Kareem, the deputy minister of the interior, told CPJ the ministry has invited Western media experts to provide security officers with training courses on how to deal with the media in a more civilized way. He said the diverse media in Kurdistan is evidence that the regional government is encouraging freedom of the press.

It’s true that there are hundreds of print, online, and broadcast news outlets in Kurdistan. But daily newspapers are dominated by the ruling parties, and often publish unedited transcripts of interviews with political leaders alongside flattering photos. Most independent outlets publish print editions solely on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. Television journalism was also long dominated by the ruling elite, but this monopoly came to an end in 2011 when Nalia Radio and Television (NRT) was established as the first private television network. All outlets maintain active websites and social media accounts, and with Internet connections strong, speedy, and largely affordable in Kurdistan—particularly compared with the rest of Iraq—most people rely on digital delivery for their news. Facebook and Twitter are popular, and the Internet allows citizens to engage in deeper debate and discussion than is found in traditional media.

“Newspapers could never play the role social media does,” said Hemin Lihony, editor-in-chief of the online edition of Rudaw News Network, adding that 85 percent of Rudaw’s Internet audience stems from Facebook and Twitter. “It is changing political parties’ stances on almost every issue. Now, before making a statement, politicians would think of the reaction it might cause in social media.”

Investigative news pieces that drill down into corruption are rare, even for independent or opposition outlets. Many journalists say self-censorship is necessary in broaching subjects such as religion, social inequality, and corruption associated with powerful officials, their families, or tribal leaders.

Twana Osman, manager of the independent television broadcaster NRT, said reporters can write about corruption, nepotism, and all sorts of illegal activities, but only in general terms. “You can say, for instance, [a particular government agency] is sunk in corruption,” Osman said. “It’s fine. But once you come down and say the leader of that institution is corrupt, that’s when the problem starts.” As a result, Osman said, news reports lack specifics and have no impact.

In this regard, Kawa Garmyane was an exception, his colleagues said. In one of the most tribal and rural regions of Kurdistan—fittingly referred to as Germyan, or the Hot Region, because of its unbearable summers—Garmyane exuded a rare bravery. His magazine, Rayel, didn’t shy away from alleging corruption by specific officials, even if they were as powerful as a military general like Sangawi. Colleagues say Garmyane enjoyed taking advantage of his writing skills to challenge authority.

“There was something that made Kawa [Garmyane] stand out among his colleagues,” said Danna Assad, an editor with independent weekly Awene, where Garmyane was also a contributor. “While other journalists were general in reporting corruption, he told us specifically who was corrupt. He named them, and, you know, that is a red line here.”

In theory, muckraking journalists like Garmyane enjoy the protection of the law in Kurdistan. The region’s press law, known as Law No. 35 of 2007, prohibits the imprisonment, harassment, or physical abuse of reporters and the closing down of publications. Many journalists working for independent and opposition media outlets accepted the law, which represented a major departure from legislation under Saddam Hussein’s dictatorial regime.

The law is progressive compared with those in other Middle East nations, but falls short of international standards because of vaguely worded prohibitions against “sowing malice and fostering hatred,” “insulting religious beliefs,” “insulting and offending religious symbols,” or divulging details of “the private lives of individuals.” Journalists say the vague wording can be interpreted arbitrarily and used by the ruling elite to stifle dissent.

Awat Ali, director of the Metro Center, told CPJ that hundreds of lawsuits are filed against journalists every year that accuse them of defamation, espionage, disrespecting religion, and “deviation from social norms.” While under the press law, no journalist is supposed to be jailed for his work, many have been detained for days or more until trial. They are often freed only after paying hundreds of dollars in bail.

In mid 2013, the Parliament passed another law that guaranteed the public the right of access to government information, similar to the Freedom of Information Act in the United States. But local journalists say that neither access nor legal protection is the problem—it is lack of law enforcement.

“Kurdistan is a region where law is not enforced, courts are not independent,” Rahman Gharib, general coordinator for the Metro Center, told CPJ.

Critics say the region’s judiciary and security systems are rigged by the two longtime ruling parties, the PUK and the KDP. Each party has its own independent militia, which act as security and police forces in their respective strongholds, responding to party leaders rather than the ministries of interior or defense. Sulaymaniyah is a PUK stronghold, while the KDP is dominant in the cities of Erbil and Duhok. Critics say the parties appoint judges on the basis of loyalty rather than on merit, and that these factors often make it impossible to get high-ranking party and government officials arrested for suspected crimes.

CPJ sought the government’s response to these criticisms and other findings of this report. The office of President Masoud Barzani did not respond to CPJ’s emailed questions.

In September 2013 parliamentary elections, the third party, Gorran, did surprisingly well, emerging as the second most popular party ahead of the PUK. Even if Gorran’s rise upsets the KDP-PUK power-sharing formula, however, the PUK is expected to remain a powerful player because of its strong military wing dominating the province of Sulaymaniyah.

As political tensions escalated in the run-up to the September 2013 elections, there was a noticeable rise in attacks on journalists. The annual number of attacks had fallen in 2012, after spiking in 2011 amid the Arab Spring.

“Whenever there is a crisis in this country, or some sort of sensitive political situation, laws, democracy, and human rights mean nothing,” Asos Hardi, an acclaimed journalist and manager of the Awene Press and Publishing Company, which publishes the independent weekly newspaper Awene, told CPJ. The number of attacks on journalists each year needs to be seen in context, said Hardi, who himself was beaten by an unidentified assailant wielding a metal object in August 2011 and needed 32 stitches. (Only the purported driver of the assailant has been punished, and despite the driver’s testimony regarding two others involved in the attack, nobody else has been charged.)

Six months after the elections, Kurdistan was still in political deadlock, without a government.

An unsolved murder

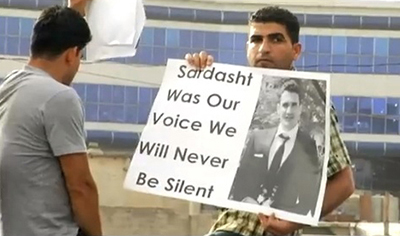

One of the most emblematic attacks on Kurdistan’s press involved a student journalist, Sardasht Osman, 23, who was studying English in his final year when he was abducted at the gates of Salahaddin University in Erbil on May 4, 2010. He was a freelancer who had contributed to the independent newspaper Ashtiname and the news websites Sbei, Kurdistan Post, Awene, Hawlati, and Lvinpress.

Osman wrote scathing articles about corruption involving high-ranking government officials and the region’s two major political parties. His death came at a time of rising political tension. The newly established Gorran, billing itself a reformist party, had done remarkably well in July 2009 elections, winning nearly one-fourth of the region’s 111 parliament seats. Voters saw unprecedented live television coverage of opposition lawmakers speaking aloud in Parliament about corruption and dodgy oil deals.

One of Osman’s most critical pieces was a tongue-in-cheek article about the family of President Barzani, leader of the KDP, called “I Am In Love With Barzani’s Daughter.” In the story, which was published in December 2009 under a pseudonym in Kurdistan Post, Osman attacked widening income inequality and wondered whether he might escape his poor origins by marrying one of Barzani’s three daughters.

Osman’s brother, Bashdar Osman, told CPJ that after the article was published his brother received multiple anonymous threats by phone and in text messages. He grew increasingly fearful. In his final article, Osman wrote of his anticipation of being murdered. “I am not afraid of death from torture,” he wrote. “I’m here waiting for my appointment with my murderers. I am praying for the most tragic death possible, to match my tragic life.”

He was abducted during the morning rush hour in Kurdistan’s capital and forced into a minibus, according to witnesses. Despite the presence of checkpoints on the Erbil-Mosul road, security forces say Osman was successfully transported to Mosul, another northern Iraqi city, where he was found dead on a road two days later with two bullets in the head.

Seventy-five Kurdish journalists, editors, and intellectuals issued a statement in May 2010, holding the regional government responsible for Osman’s death. “This work is beyond the capability of one person or one small group,” the statement said. “We believe the Kurdistan Regional Government and its security forces are responsible first and foremost and they are supposed to do everything in order to find this evil hand.”

On May 10, 2010, hundreds of university students marched from where Osman was abducted and tried to storm Parliament, chanting: “Whose hands are stained with the blood of Sardasht?” Parliament Speaker Kamal Kirkuki, a member of the KDP, tried to address the crowd, but protesters threw water bottles and shoes at him until he was forced to leave the podium.

Shortly after the murder, Barzani said he appointed a committee to investigate the crime but did not identify the group’s members. There is little information available about whether the committee ever met or even existed.

Five months later, however, security forces televised a taped confession of a man named Hisham Mahmoud Ismaeel, who said that he had been the driver of the minibus that carried Osman to Mosul. Identifying himself as a member of Ansar al-Islam, a group affiliated with Al-Qaeda, Ismaeel said Osman was killed because he had failed to carry out some unspecified work for the Islamist group. But in a statement published in local media, Ansar al-Islam denied its involvement. Members of Osman’s family told reporters they were threatened by government forces after speaking out against the notion that Osman had ties to a terrorist group. Ismaeel is still in prison, according to security forces.

CPJ and other local and international rights groups criticized the inquiry for lacking credibility and transparency. It outraged others, too. In a newspaper column, Bachtyar Ali, a prominent Iraqi Kurdish novelist, called the finding a “brazen lie.” His colleagues said they had known Osman as a leftist, liberal, and secular man—not a religious fanatic.

Bashdar Osman told CPJ that he was so outspoken about government involvement in his brother’s murder that he feared for his own life and fled Kurdistan for Europe, and only recently returned to visit Kurdistan. In a phone interview with CPJ, he said he continues to believe that the government investigation into his brother's death was fabricated. "Everything—from A to Z—was a lie and made up," he said. "His death changed our life forever. It changed many things in the lives of the people of Kurdistan, too. Sardasht's issue has now become the issue of freedom." He said only an impartial inquiry led by members of international organizations could identify "the real murderer."

A brazen arson attack

Months after Osman’s death, the Arab Spring protests sweeping North Africa and the Middle East reached Iraqi Kurdistan. On February 17, 2011, thousands of Kurds in Sulaymaniyah began protesting, calling for an end to corruption and the authoritarian rule of the region’s leaders.

At the time, a number of prominent independent journalists established NRT, the territory’s first private television network. NRT started its broadcast with strong coverage of the protests, relaying live images of people chanting slogans that questioned the legitimacy of Barzani and Jalal Talabani, who heads the PUK, the second most powerful party, and holds the ceremonial post of Iraqi president. (Talabani suffered a stroke in late 2012 and has been outside the country since, according to news reports.)

Shortly after its launch, the television station received a phone call with a chilling message, according to Twana Osman, NRT’s manager (no relation to the slain journalist Sardasht Osman): “You either stop airing the protest or pay a price for it.” The television station chose the latter. On a dark winter night in February 2011, a few days after its launch, dozens of armed men broke into NRT’s headquarters and torched the entire building. The studios were empty at the time and no one was injured.

Three years later, there have been no arrests. In March 2011, Barham Salih, then prime minister of Kurdistan, declared in Parliament that the Court of Sulaymaniyah had issued arrest warrants for “eight or nine people” accused of having played some role in the attack on NRT. “Two of them are known,” said Salih. “One of them belongs to the Anti-Terror Agency. The other belongs to the Ministry of Peshmarga (Defense).” Without further elaboration, Salih promised to do everything possible to bring the perpetrators to justice.

Nearly a week later, the two men to whom Salih alluded did appear in court, according to NRT. The station reported that one suspect was the head of the intelligence operations of the Ministry of Peshmarga, while the other was the head of the intelligence department of the Anti-Terror Agency, a special army counter-terrorist unit. NRT did not report the suspects’ names.

At the trial, both officials denied involvement in the attack and neither was jailed. NRT reported that security forces and bodyguards of the suspects gathered outside and inside the court building. Without naming sources, NRT said one brought receipts to trial to prove he was away from Sulaymaniyah at the time of the attack on NRT, while the other disputed his involvement by saying, “I’m too fat”—implying that a commando-style raid would require physical fitness. Physical responsibility for the arson, however, was not the main issue to be resolved.

Because the two men work in intelligence, their identities are secret and CPJ could not reach out to either official for comment.

The unresolved case of NRT has left journalists particularly disappointed about the effectiveness of the judiciary and law enforcement agencies in Kurdistan. It remains a mystery how someone could get away with burning down an entire television station in one of the safest, most guarded, and upscale residential areas of Sulaymaniyah. NRT is based in German Village, a newly built gated community where affluent expatriates can afford to live.

In August 2013, a CPJ researcher visited the television station for an update. NRT continues to exist as a powerful medium. The headquarters is renovated. Its reporters seem determined. The inner walls of the new offices are decked with pictures of the debris of what used to be their workplace.

But Twana Osman told CPJ that he has become completely disillusioned with Kurdistan’s whole system of governance.

“Those who have burnt the station are part of a group that is bigger than the government,” Osman said, adding that there was sufficient evidence available for an independent court to arrive at a conclusive result. “If the court is serious about it—if it were independent in the first place—we would easily be able to tell who the criminals are,” he said.

CPJ asked Jalal Kareem, the deputy minister of interior, why the NRT attackers remain at large. His response included an implied acknowledgment that some people are above the law in Kurdistan: “[Osman] knows who burnt it down,” Kareem said. “The court also knows who burnt it down.” He suggested that the actual attackers might have left Iraq for a foreign country.

Rahman Gharib, the coordinator for the Metro Center, said he believes Kurdistan’s judicial system is not independent. “All the judges are appointed on the basis of their loyalty to the ruling parties,” he said.

Rawand Maasum, a judge serving as an official at the Ministry of Justice, disputes this. “All of us have had some party position before,” he said. “But courts are sacred places. When we step into them, we strip ourselves of party affiliations. We act independently,” he said.

With the criminal case unlikely to be resolved in court, NRT has shifted its focus from finding the perpetrators to seeking compensation for the damages it suffered. Parliament passed an ad hoc resolution on February 23, 2011, ordering the government to compensate NRT and other damaged media organizations “according to the law.” Based on the resolution, the Court of Sulaymaniyah has ruled that the government is obligated to compensate NRT with US$15 million, according to Ferhad Hatem, Sulaymaniyah’s attorney general.

Osman told CPJ that NRT has yet to receive the compensation, but he is optimistic that his channel will get the money soon. He said the outstanding issue is not if NRT should be paid for its losses, but how much.

Perversely, the government’s willingness to reimburse NRT has strengthened the widespread public belief that people in positions of power—either party or government officials—must have carried out the attack on the television network, because otherwise the government would not be willing to pay such a large sum of money to a private corporation.

The criticism comes from beyond journalists. Hatem, Sulaymaniyah’s attorney general, has appealed the ruling in the Court of Sulaymaniyah, arguing that there is no legal basis for such compensation.

“I don’t want to hide it from you. There is a political aspect to this,” he told CPJ. “Just ask yourself this question: Where in the world does the government compensate for a crime it has not committed?”

Osman says NRT sometimes tries to cover sensitive stories, but in at least one instance it could not: the first anniversary of the attack on NRT.

A long, investigative documentary was produced and scheduled to air under the title: “Who Burnt Down NRT?”

The film’s promotion aired for days. Despite anonymous phone calls warning the station not to broadcast the documentary, it went on air as scheduled. Then, in a matter of minutes, viewers lost the NRT signal in their homes. Osman said NRT received another warning over the phone: “Last time, we just burned down the television [station],” said the unidentified caller. “This time, we will burn it down with all of you inside it.” The documentary was never broadcast.

In October 2013, while NRT’s attackers still remained at large, the television station itself became news again. Its owner, Shaswar Abdulwahid, was shot and wounded in Sulaymaniyah. He survived. But, again, the attackers committed their crime with impunity.

A case of legal harassment

Not every violation against the media in Kurdistan is as brazen as arson or murder. Lawsuits and arbitrary detentions are also effective mechanisms for threatening, harassing, or intimidating journalists into keeping silent.

Sherwan Sherwani, the editor-in-chief of Bashur, a critical magazine based in Dohuk province, was arrested without a warrant on April 20, 2012, and detained for several days over two articles alleging public corruption. He was allowed to leave prison on bail of 1 million Iraqi dinars (about US$858 at current exchange rates). He told reporters that he had been arrested for political reasons. He also disparaged Kurdistan’s legal system, likening it to “the rule of qereqush” or “the rule of the tyrant”—prompting the court to punish him with a fine of 200,000 Iraqi dinars (about US$150) for insulting a public institution, he said.

Because of his journalistic work, Sherwani has been prosecuted multiple times.

In 2013, he was sued for defamation by Bahzad Barzani, a nephew of the president, in connection with an article in Bashur alleging that armed forces loyal to the nephew operate a detention facility jailing dozens of political prisoners. Sherwani told CPJ, “This is an illegal prison, where dozens of people have been tortured to death or have committed suicide.”

Sherwani said he learned of an arrest warrant against him only after neighbors notified him of a police raid on his home while he was away in December 2013. Bahzad Barzani denied allegations that he had sent forces to raid the journalist’s home and said the police merely implemented a court order to arrest him. Barzani’s lawyer, Sardar Raqib Najim, said the arrest warrant was issued in June 2013 but the police had failed to arrest Sherwani because of difficulty finding him.

In an interview with CPJ on December 20, 2013, Bahzad Barzani confirmed that he had filed the defamation lawsuit. Sherwani “has published some stuff about me in his magazine that has no basis,” Bahzad Barzani said. “In the article, he has accused me of killing innocent people. He should come to the court and prove that I have killed people. If he lied, he should be held accountable for that. If he told the truth, then the court should deal with me as a murderer.”

On December 22, 2013, Sherwani appeared in court to testify and was once again released on bail of 1 million Iraqi dinars. The trial has been delayed indefinitely. Sherwani stands by his story and says he has three witnesses who have been subjected to torture in the alleged prison, but are fearful of retribution for testifying unless their identities are protected by the court.

Sherwani told CPJ that he no longer considers his home a safe place, as it could at any time be raided by security or police forces loyal to the KDP. “I’m always somewhere between Sulaymaniyah, Erbil, and Duhok,” he said.

Namo Abdulla is an Iraqi Kurdish journalist based in Washington, D.C., who studied journalism at Columbia University. He is Washington Bureau Chief for Rudaw, a 24-hour news channel in Kurdistan, and hosts a weekly, English-language political talk show called “Inside America.” His writing has appeared in international publications such as Al-Jazeera English, Reuters, and The New York Times.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The 17th paragraph of this report has been corrected to reflect that most independent papers publish only on a weekly or bi-weekly basis--not all independent papers as stated previously.

CPJ's Recommendations

To the Kurdish Regional Government:

- Thoroughly investigate all unsolved attacks on journalists, including the murders of Sardasht Osman and Kawa Garmyane and the arson attack on Nalia Radio and Television (NRT), and hold to account all those responsible to the full extent of the law. Ensure that the families of killed or disappeared journalists are able to seek the truth about the fate of their relatives without fear of reprisal.

- Publicly disclose the findings of the committee appointed by the president to investigate the murder of Sardasht Osman and any other official inquiries into attacks on journalists.

- Provide training and education to judiciary and security officials to ensure no journalist is illegally detained in relation to his or her work. Publicly condemn instances of illegal detention and hold those responsible to account.

- Take steps to amend the press law in consultation with local journalists, with the goal of banning vaguely worded prohibitions that are open to abuse and politicized prosecutions.

To the leaders of Kurdish political parties:

- State publicly that your party encourages open debate and criticism and does not condone violence or other actions aimed at intimidating the press, including by security forces. Work actively to educate supporters about the law’s protection of journalists.

To the international community:

- UNESCO, working under the U.N. Action Plan on Security of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, should work with the Kurdistan Regional Government to develop and improve legislation and mechanisms to safeguard journalists and guarantee freedom of expression and information.

- Civil society groups should work with the Kurdistan Regional Government to promote rule of law through training programs and the establishment of strong, independent government institutions.

- Bilateral and multilateral trade partners should specify freedom of the press in negotiations over trade and investment with the Kurdistan Regional Government.