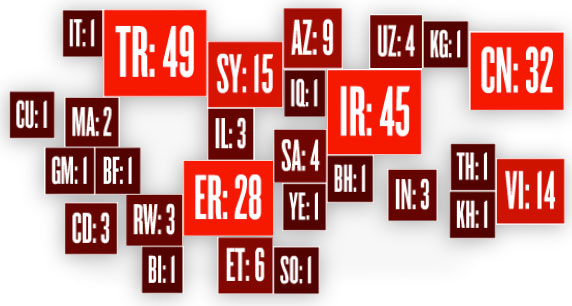

232 journalists jailed worldwide

As of December 1, 2012

Analysis: A record high | Video: Free the press | Audio: From a Cuban prison

CPJ Blog: Turkey’s path forward | Rwanda’s injustice

Click on a country name to see summaries of individual cases.

Medium You need to upgrade your Flash Player

|

Charges You need to upgrade your Flash Player

|

Freelance / Staff You need to upgrade your Flash Player

|

Azerbaijan: 9

Aidyn Dzhaniyev, Khural

Imprisoned: September 7, 2011

Regional authorities in Lenkoran, southeastern Azerbaijan, arrested Dzhaniyev on allegations of insulting a local woman and transferred him to a Baku detention facility. Later, while Dzhaniyev was in pretrial detention, authorities also accused him of breaking windows at a Lenkoran mosque, news reports said. Dzhaniyev, a reporter with the independent daily Khural, denied the accusations.

On November 21, 2011, a regional court convicted Dzhaniyev of hooliganism and sentenced him to three years in jail, local press reports said. His appeal was denied. An independent investigation by local journalists, cited by the independent Azerbaijani news agency Turan, concluded that the charges came in reprisal for Dzhaniyev’s reporting on allegations that Lenkoran religious leaders were involved in drug trafficking.

CPJ has documented a pattern in which Azerbaijani authorities have filed retaliatory charges against critical journalists covering sensitive issues. CPJ has found those charges to be unsubstantiated.

Avaz Zeynally, Khural

Imprisoned: October 28, 2011

Authorities in Baku arrested Zeynally, editor of the independent daily Khural, on bribery and extortion charges stemming from a complaint filed by Gyuler Akhmedova, a member of Azerbaijani parliament. Akhmedova alleged that the editor had tried to extort 10,000 manat (US$12,700) from her in August 2011, regional and international press reports said. The day after his arrest, a district court in Baku sanctioned Zeynally’s pretrial imprisonment for three months, the independent Caucasus news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported. Authorities also confiscated all of Khural‘s reporting equipment, citing the newsroom’s inability to pay damages in a 2010 defamation lawsuit filed by presidential administration officials. Khural now publishes online only.

Zeynally denied all charges and described a much different encounter with Akhmedova, Kavkazsky Uzel reported. In September 2011, Zeynally reported in Khural that Akhmedova had offered him money in exchange for his paper’s loyalty to authorities. He reported that he had refused the offer. In September 2012, Akhmedova resigned from parliament after a video surfaced on the Internet that purported to show her demanding a bribe from a potential candidate in exchange for a seat in parliament.

Emin Huseynov, director of the Baku-based Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, told CPJ that weeks before Zeynally’s arrest, his paper had criticized President Ilham Aliyev’s repressive policies toward independent journalists and opposition activists. Zeynally had published two commentaries in Khural that were especially critical of the administration. In the first, he disparaged comments made by Aliyev in an Al-Jazeera interview that painted a glowing picture of the country’s development. In the second, Zeynally accused the government of retaliatory prosecution against Khural, Huseynov told CPJ.

Authorities have extended Zeynally’s pretrial detention several times. A trial began in May 2012 but was pending in late year. If convicted, Zeynally faces up to 12 years in jail.

Anar Bayramli, Sahar TV and Fars

Imprisoned: February 22, 2012

Baku police visited Bayramli’s home, summoned him for interrogation, and detained him after declaring they had found 0.387 grams of heroin in his jacket, news reports said. Bayramli, a Baku-based correspondent for the Iranian Sahar TV and Fars news agency, denied the accusations and said police planted the drugs. In June 2012, the Binagadinsky District Court convicted Bayramli of drug possession and sentenced him to two years in prison, the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported.

The arrest came at a time of heightened tension between the Azerbaijani and Iranian governments. Tehran had accused Azerbaijan of helping Israel assassinate an Iranian nuclear scientist; Baku had claimed Iran was plotting attacks in Azerbaijan.

Local rights activists told CPJ they believed that police planted the drugs in retaliation for Bayramli’s journalism. In his broadcasts, Bayramli often reported on Azerbaijan’s human rights record and criticized Azerbaijani foreign policy, including its supposed cooperation with Israel. Prior to his arrest, police told Bayramli several times to visit their headquarters for what they termed “a conversation,” during which they urged him to stop working for Iranian media, Emin Huseynov of the Baku-based Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety told CPJ.

In an interview interpreted by Huseynov, the journalist’s lawyer said Bayramli took off his jacket at the district police headquarters and left it in the lobby before entering the office of the local police chief. As the journalist was about to leave the building after the meeting, police agents suddenly asked him to reveal the contents of his jacket and found heroin.

Bayramli denied the drug charges in court and said he was being persecuted for his journalism. “If Azerbaijan had an independent court, it would certainly release me,” he told the court. “But since courts in our country are an appendage of the state, I don’t expect a fair verdict.” CPJ has documented a recent pattern of cases in which Azerbaijani authorities have filed questionable drug charges against journalists whose coverage has been at odds with official views.

Vugar Gonagov, Khayal TV

Zaur Guliyev, Khayal TV

Imprisoned: March 13, 2012

Authorities arrested Gonagov, director of the regional TV channel Khayal, and Guliyev, Khayal’s chief editor, on charges of inciting mass disorder, local press reports said. Guliyev was also accused of abuse of office, the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported. The charges stemmed from March riots in the northeastern city of Quba, which began when a video posted on YouTube showed a regional governor making insulting comments to local residents. Following the riots, the governor was ousted.

Authorities accused Guliyev and Gonagov of uploading the video and causing “mass unrest.” Both men denied the charges. They were placed in a Baku detention facility without access to defense lawyers; local media reports said they were tortured in custody. Authorities extended the journalists’ pretrial detention several times, arguing that investigators needed more time to bring a case to trial, news reports said. Guliyev faced up to 10 years in jail and Gonagov up to three years.

Faramaz Novruzoglu (Faramaz Allahverdiyev), freelance

Imprisoned: April 18, 2012

A Nizami District Court in Baku sentenced Novruzoglu, also known as Faramaz Allahverdiyev, to four and a half years in prison on charges of illegal border crossing and inciting mass disorder, the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported. Novruzoglu denied the accusations and said they had been fabricated in retaliation for his investigative stories on government corruption published in the independent newspaper Milletim and on social networking websites.

Novruzoglu was accused of calling for mass disobedience on a Facebook page under the name of Elchin Ilgaroglu, news reports said. Authorities also accused him of illegally crossing the border into Turkey in November 2010, Kavkazsky Uzel reported. During his trial, Novruzoglu said investigators found no evidence connecting him to the Facebook page, Kavkazsky Uzel reported. He also presented the court with his passport, which showed other travel during the time that he was accused of having crossed the border into Turkey, reports said.

Emin Huseynov, director of the Baku-based Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, told CPJ that investigators failed to present any credible evidence against the journalist and that the state-appointed defense attorney did not effectively defend him in court. According to Huseynov and Kavkazsky Uzel, Novruzoglu and his colleagues said they believed that he was targeted in retaliation for critical articles he wrote on high-level corruption in the export of Azerbaijani crude oil and the import of Russian timber.

Nijat Aliyev, Azadxeber

Imprisoned: May 20, 2012

Baku police arrested Aliyev, editor-in-chief of the independent news website Azadxeber, near a subway station in downtown Baku, and charged him with illegal drug possession. A local court ordered that Aliyev be held in pretrial detention.

Colleagues disputed the charges and said they were in retaliation for his journalism. Aliyev’s deputy, Parvin Zeynalov, told local journalists that the outlet’s critical reporting on the government’s religion policies could have prompted the editor’s arrest.

Aliyev’s lawyer, Anar Gasimli, told the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety, or IRFS, that investigators tortured the journalist in custody and pressured him to admit he had drugs in his possession. According to IRFS, Gasimli said police also threatened to plant narcotics in the editor’s apartment and file “more serious” charges against him. No trial date had been set by late year.

CPJ has documented a recent pattern of cases in which Azerbaijani authorities have filed questionable drug charges against journalists whose coverage has been at odds with official views.

Hilal Mamedov, Talyshi Sado

Imprisoned: June 21, 2012

Baku police detained Mamedov, editor of minority newspaper Talyshi Sado (Voice of the Talysh), after allegedly finding about five grams of heroin in his pocket, according to the Azeri-language service of the U.S. government-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. On the day of his arrest, Mamedov went to visit his relative in a hospital and did not return home as promised, his family members told journalists.

Following his arrest, Baku police raided the journalist’s home and said they found another 30 grams of heroin, news reports said. The next day, a district court in Baku ordered Mamedov to be imprisoned for three months before trial on drug possession charges, the reports said. Mamedov’s family claimed police had planted the drugs, and colleagues said they believed the editor had been targeted in retaliation for his reporting, the reports said.

Talyshi Sado covers issues affecting the Talysh ethnic minority group in Azerbaijan. Mamedov’s own articles have been published in Talyshi Sado and on regional and Russia-based news websites, according to Emin Huseynov, director of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety. Huseynov also told CPJ that Mamedov had investigated the 2009 death in prison of Novruzali Mamedov, Talyshi Sado‘s former chief editor.

CPJ has documented a recent pattern of cases in which Azerbaijani authorities have filed questionable drug charges against journalists whose coverage has been at odds with official views.

In July, authorities brought another set of politically motivated charges against Mamedov, lodging separate counts of treason and incitement to ethnic and religious hatred, news reports said. Azerbaijan’s Interior Ministry said in a statement that Mamedov had undermined the country’s security in his articles for Talyshi Sado, in his interviews with the Iranian broadcaster Sahar TV, and in unnamed books that he had allegedly translated and distributed. The statement also denounced domestic and international protests against Mamedov’s imprisonment and said the journalist had used his office to spy for Iran.

Mamedov awaited trial in late year. If convicted, he faces a life term in prison, Reuters reported.

Araz Guliyev, Xeber 44

Imprisoned: September 8, 2012

Guliyev, chief editor of news website Xeber 44, which focuses on religious topics, was arrested on hooliganism charges while reporting on a protest in the southeastern city of Masally, the independent regional news website Kavkazsky Uzel reported. The rally was staged by local residents protesting against partially clad dancers who performed at a government-sponsored folklore festival in Masally.

According to news reports, the protesters called on the festival organizers to respect religious traditions of the local residents, but police detained the protesters and charged them with hooliganism. Two days later, a regional court ordered Guliyev jailed for two months pending trial.

Guliyev’s brother, Azer, told Kavkazsky Uzel that the journalist did not participate in the protest but covered it for his website. Guliyev’s imprisonment could also be related to his reporting on local residents’ protests against an official ban on headscarves and veils in public schools, his brother told Kavkazsky Uzel.

Bahrain: 1

Abduljalil Alsingace, freelance

Imprisoned: March 17, 2011

Alsingace, a journalistic blogger and human rights defender, was among a number of high-profile government critics arrested as the government renewed its crackdown on dissent after pro-reform protests swept the country in February 2011.

In June 2011, a military court sentenced Alsingace to life imprisonment for “plotting to topple the monarchy.” In all, 21 bloggers, human rights activists, and members of the political opposition were found guilty on similar charges and handed lengthy sentences. (Ali Abdel Imam, another journalistic blogger, was sentenced to 15 years in prison but was in hiding in late year.)

The High Court of Appeal upheld Alsingace’s conviction and life sentence in September 2012. It similarly upheld the harsh rulings against his co-defendants. The defendants planned to appeal to the Court of Cassation, which is nation’s highest court.

On his blog, Al-Faseela (Sapling), Alsingace wrote critically about human rights violations, sectarian discrimination, and repression of the political opposition. He also monitored human rights for the Shia-dominated opposition Haq Movement for Civil Liberties and Democracy.

Alsingace had been first arrested on anti-state conspiracy charges in August 2010 as part of widespread reprisals against political dissidents, but was released briefly in February 2011 as part of a government effort to appease a then-nascent protest movement.

Burkina Faso: 1

Lohé Issa Konaté, L’Ouragan

Imprisoned: October 29, 2012

Konaté, editor of the private weekly L’Ouragan, was taken into custody after a judge in the capital, Ouagadougou, sentenced him to one year in prison on criminal charges of defaming state prosecutor Placide Nikiéma, news reports said.

Nikiéma filed a complaint in response to August articles alleging the prosecutor’s office mishandled a counterfeiting case and an inheritance dispute. Nikiéma denied the allegations, news reports said.

Konaté was also fined 1.5 million CFA francs (US$2,900) and ordered to pay damages of 4 million CFA francs (US$7,800) to the plaintiff. The judge also banned L’Ouragan from circulation for six months. Defense lawyer Halidou Ouédraogo said an appeal would be filed, news reports said, but Konaté was imprisoned after the sentencing.

The judge convicted Roland Ouédraogo, a contributor to L’Ouragan, in connection with the coverage and issued a warrant for his arrest, according to local journalists. The judge imposed the same sentence against Ouédraogo, who was still at large in late year. Konaté was held at Maison d’Arrêt et de Correction de Ouagadougou.

Burundi: 1

Hassan Ruvakuki, Radio Bonesha and Radio France Internationale

Imprisoned: November 28, 2011

Agents from the Burundian National Intelligence Service arrested Ruvakuki, a reporter for the private broadcaster Radio Bonesha and correspondent for the French government-funded Radio France Internationale, as he covered a press conference in the capital, Bujumbura, according to local journalists. He was held without access to a lawyer for two days before Télésphore Bigiriman, a spokesman for the country’s intelligence agency, confirmed his arrest in an interview with Agence France-Presse, according to news reports.

Local journalists said Ruvakuki was arrested in connection with a November 2011 trip he took to a rebel-held area along Burundi’s border with Tanzania, during which he recorded a statement from Pierre Claver Kabirigi, a former police officer who claimed to be the leader of a new rebel group, according to local journalists. The arrest came amid a government clampdown on coverage of the group. Radio Publique Africaine, another independent station, had also aired a recent interview with Kabirigi. The government-controlled media regulatory agency issued a directive forbidding coverage that could “undermine the security of the population.”

In June 2012, a court in the eastern town of Cankuzo found Ruvakuki guilty of “participating in terrorist attacks” under the penal code and sentenced him to life imprisonment, Patrick Nduwimana, interim director of Radio Bonesha, told CPJ. The defense raised numerous questions about the fairness of the legal proceedings, challenging the impartiality of the judges hearing the case, and saying they had blocked defense access to prosecution files. An appeal was pending in late year.

Cambodia: 1

Mam Sonando, Beehive Radio

Imprisoned: July 15, 2012

More than 20 police officers arrested Sonando, owner, director, and political commentator of the independent broadcaster Beehive Radio, at his home in Phnom Penh. The journalist was charged with orchestrating an insurrection in Kratie province, where villagers had clashed with security forces over a land dispute with a private Russian company in May, news reports said.

On October 1, Phnom Penh Municipal Court convicted Sonando of inciting a rebellion and sentenced him to 20 years. Another alleged plotter, Bun Ratha, was sentenced in absentia to 30 years in prison, while three others were handed sentences ranging from 10 months to three years. Sonando, who holds both Cambodian and French citizenship, maintained his innocence during the trial and appealed the verdict, according to news reports.

Local and international rights groups said they believed Sonando’s imprisonment was motivated by his station’s critical coverage of the government. On June 25, Sonando reported on a local dissident group’s presentation to the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in the Hague. The group accused the Cambodian government of crimes against humanity. In a nationally broadcast speech the next day, Prime Minister Hun Sen said Sonando should be arrested for plotting to “overthrow the government” and establishing “a state within a state.” A day later, a warrant was issued for the journalist’s arrest.

This was the third time Sonando had been imprisoned for his reporting. He was jailed in 2003 and 2005 on anti-state charges related to his news coverage.

China: 32

Kong Youping, freelance

Imprisoned: December 13, 2003

Kong, an essayist and poet, was arrested in Anshan, Liaoning province. A former trade union official, he had written online articles that supported democratic reforms, appealed for the release of then-imprisoned Internet writer Liu Di, and called for a reversal of the government’s “counterrevolutionary” ruling on the pro-democracy demonstrations of 1989.

Kong’s essays included an appeal to democracy activists in China that stated, “In order to work well for democracy, we need a well-organized, strong, powerful, and effective organization. Otherwise, a mainland democracy movement will accomplish nothing.” Several of his articles and poems were posted on the Minzhu Luntan (Democracy Forum) website.

In 1998, Kong served time in prison after he became a member of the Liaoning province branch of the opposition China Democracy Party (CDP). In 2004, he was tried on subversion charges along with co-defendant Ning Xianhua, who was accused of being the vice chairman of the CDP branch in Liaoning, according to the U.S.-based advocacy organization Human Rights in China and court documents obtained by the U.S.-based Dui Hua Foundation. Later that year, the Shenyang Intermediate People’s Court sentenced Kong to 15 years in prison, plus four years’ deprivation of political rights. His sentence was reduced to 10 years on appeal, according to the Independent Chinese PEN Center.

Kong suffered from hypertension and was imprisoned in the city of Lingyuan, far from his family. The group reported that his eyesight was deteriorating. Ning, who received a 12-year sentence, was released ahead of schedule on December 15, 2010, according to Radio Free Asia.

Shi Tao, freelance

Imprisoned: November 24, 2004

Shi, former editorial director of the Changsha-based newspaper Dangdai Shang Bao (Contemporary Trade News), was detained near his home in Taiyuan, Shanxi province, in November 2004.

He was formally charged with “providing state secrets to foreigners” in connection with an email sent on his Yahoo account to the U.S.-based editor of the website Minzhu Luntan (Democracy Forum). In the email, sent anonymously in April 2004, Shi transmitted notes from the local propaganda department’s recent instructions to his newspaper. The directive prescribed coverage of the outlawed Falun Gong and the anniversary of the military crackdown on demonstrators at Tiananmen Square. The National Administration for the Protection of State Secrets retroactively certified the contents of the email as classified, the official Xinhua News Agency reported.

On April 27, 2005, the Changsha Intermediate People’s Court found Shi guilty and sentenced him to a 10-year prison term. In June of that year, the Hunan Province High People’s Court rejected his appeal without granting a hearing. He is being held at Yinchuan Prison in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region.

Court documents in the case revealed that Yahoo had supplied information to Chinese authorities that helped them identify Shi as the sender of the email. Yahoo’s participation in the identification of Shi and other jailed dissidents raised questions about the role that international Internet companies play in the repression of online speech in China and elsewhere.

In November 2005, CPJ honored Shi with its annual International Press Freedom Award for his courage in defending the ideals of free expression. In November 2007, members of the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs rebuked Yahoo executives for their role in the case and for wrongly testifying in earlier hearings that the company did not know the Chinese government’s intentions when it sought Shi’s account information.

Yahoo, Google, and Microsoft later joined with human rights organizations, academics, and investors to form the Global Network Initiative, which adopted a set of principles to protect online privacy and free expression in October 2008. Human Rights Watch awarded Shi a Hellman/Hammett grant for persecuted writers in October 2009.

Yang Tongyan (Yang Tianshui), freelance

Imprisoned: December 23, 2005

Yang, commonly known by his penname Yang Tianshui, was detained along with a friend in Nanjing, eastern China. He was tried on charges of “subverting state authority,” and on May 17, 2006, the Zhenjiang Intermediate People’s Court sentenced him to 12 years in prison.

Yang was a well-known writer and member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. He was a frequent contributor to U.S.-based websites banned in China, including Boxun News and Epoch Times. He often wrote critically about the ruling Communist Party and advocated for the release of jailed Internet writers.

According to the verdict in Yang’s case, which was translated into English by the U.S.-based Dui Hua Foundation, the harsh sentence against him was related to a fictitious online election, established by overseas Chinese citizens, for a “democratic Chinese transitional government.” His colleagues said that he had been elected to the leadership of the fictional government without his prior knowledge. He later wrote an article in Epoch Times in support of the model.

Prosecutors also accused Yang of transferring money from overseas to Wang Wenjiang, a Chinese dissident who had been convicted of endangering state security and jailed. Yang’s defense lawyer argued that this money was humanitarian assistance to Wang’s family and should not have constituted a criminal act.

Believing that the proceedings were fundamentally unjust, Yang did not appeal. He had already spent 10 years in prison for his opposition to the military crackdown on demonstrators at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

In June 2008, Shandong provincial authorities refused to renew the law license of Yang’s lawyer, press freedom advocate Li Jianqiang. In 2008, the PEN American Center announced that Yang had received the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award.

Relatives who visited Yang in prison in August 2012 said he was receiving poor treatment for a number of medical conditions including tuberculosis, arthritis, and diabetes, according to international news reports.

Qi Chonghuai, freelance

Imprisoned: June 25, 2007

Police in Tengzhou arrested Qi, a journalist of 13 years, in his home in Jinan, the provincial capital, and charged him with fraud and extortion. He was convicted and sentenced to four years in prison on May 13, 2008. The arrest occurred about a week after police detained Qi’s colleague, Ma Shiping, a freelance photographer, on charges of carrying a false press card.

Qi and Ma had criticized a local official in Shandong province in an article published June 8, 2007, on the website of the U.S.-based Epoch Times, according to Qi’s lawyer, Li Xiongbing. On June 14, the two had posted photographs on Xinhua news agency’s anti-corruption Web forum that showed a luxurious government building in the city of Tengzhou.

Qi was accused of taking money from local officials while reporting several stories, a charge he denied. The people from whom he was accused of extorting money were local officials threatened by his reporting, Li said. Qi told his lawyer and his wife, Jiao Xia, that police beat him during questioning on August 13, 2007, and again during a break in his trial.

Qi was scheduled for release in 2011. In May, local authorities told him that the court had received new evidence against him. On June 9, less than three weeks before the end of his term, a Shandong provincial court sentenced him to another eight years in jail, according to the New York-based advocacy group Human Rights in China and Radio Free Asia.

Ma was sentenced in late 2007 to one and a half years in prison. He was released in 2009, according to Jiao.

Human Rights in China, citing an online article by defense lawyer Li Xiaoyuan, said the court tried Qi on a new count of stealing advertising revenue from China Security Produce News, a former employer.The journalist’s supporters speculated that the new charge came in reprisal for Qi’s statements to his jailers that he would continue reporting after his release, according to The New York Times.

Qi was being held in Tengzhou Prison, a four-hour trip from his family’s home, which limited visits. Jiao told international journalists in 2012 that her husband had offered her a divorce, but that she declined.

Dhondup Wangchen, Filming for Tibet

Imprisoned: March 26, 2008

Police in Tongde, Qinghai province, arrested Wangchen, a Tibetan documentary filmmaker, shortly after he sent footage filmed in Tibet to his colleagues, according to the production company Filming for Tibet. A 25-minute film titled “Jigdrel” (Leaving Fear Behind) was produced from the tapes.

Officials in Xining, Qinghai province, charged the filmmaker with inciting separatism and replaced the Tibetan’s own lawyer with a government appointee in July 2009, according to international reports. On December 28, 2009, the Xining Intermediate People’s Court in Qinghai sentenced Wangchen to six years’ imprisonment on subversion charges, according to a statement issued by his family.

Filming for Tibet was founded in Switzerland by Gyaljong Tsetrin, a relative of Wangchen who left Tibet in 2002 but maintained contact with people there. Tsetrin told CPJ that he had spoken to Wangchen on March 25, 2008, but lost contact after that. He learned of the detention only later, after speaking by telephone with relatives.

Filming for the documentary was completed shortly before peaceful protests against Chinese rule of Tibet deteriorated into riots in Lhasa and in Tibetan areas of China in March 2008. The filmmakers had gone to Tibet to ask ordinary people about their lives under Chinese rule in the run-up to the Beijing Olympics.

The arrest was first publicized when the documentary was screened before a small group of international reporters in a hotel room in Beijing on August 6, 2008. A second screening was interrupted by hotel management, according to Reuters.

Wangchen was born in Qinghai but moved to Lhasa as a young man, according to his published biography. He had recently relocated with his wife, Lhamo Tso, and four children to Dharamsala, India, before returning to Tibet to begin filming, according to a report published in October 2008 by the South China Morning Post. Lhamo Tso told Radio Netherlands Worldwide in 2011 that her husband was working extremely long hours in prison and had contracted hepatitis B.

In March 2008, Wangchen’s assistant, Jigme Gyatso, was arrested, then released on October 15, 2008, Filming for Tibet said. Gyatso described having been brutally beaten by interrogators during his seven months in detention, according to Filming for Tibet. The Dharamsala-based Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy reported that Gyatso was re-arrested in March 2009 and released the next month. The film company reported in October 2012 that Gyatso had been missing since September 20 and that it feared he had been detained again.

CPJ honored Wangchen with an International Press Freedom Award in 2012.

Liu Xiaobo, freelance

Imprisoned: December 8, 2008

Liu, a longtime advocate for political reform and the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was imprisoned for “inciting subversion” through his writing. Liu was an author of Charter 08, a document promoting universal values, human rights, and democratic reform in China, and was among its 300 original signatories. He was detained in Beijing shortly before the charter was officially released, according to international news reports.

Liu was formally charged with subversion in June 2009, and he was tried in the Beijing Number 1 Intermediate Court in December of that year. Diplomats from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Sweden were denied access to the trial, the BBC reported. On December 25, 2009, the court convicted Liu of “inciting subversion” and sentenced him to 11 years in prison and two years’ deprivation of political rights.

The verdict cited several articles Liu had posted on overseas websites, including the BBC’s Chinese-language site and the U.S.-based websites Epoch Times and Observe China, all of which had criticized Communist Party rule. Six articles were named-including pieces headlined, “So the Chinese people only deserve ‘one-party participatory democracy?'” and “Changing the regime by changing society”-as evidence that Liu had incited subversion. Liu’s income was generated by his writing, his wife told the court.

The court verdict cited Liu’s authorship and distribution of Charter 08 as further evidence of subversion. The Beijing Municipal High People’s Court upheld the verdict in February 2010.

In October 2010, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Liu its 2010 Peace Prize “for his long and nonviolent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.” His wife, Liu Xia, has been kept under house arrest in her Beijing apartment since shortly after her husband’s detention, according to international news reports. Authorities said she could request permission to visit Liu every two or three months, the BBC reported.

Kunchok Tsephel Gopey Tsang, Chomei

Imprisoned: February 26, 2009

Public security officials arrested Tsang, an online writer, in Gannan, a Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in the south of Gansu province, according to Tibetan rights groups. Tsang ran the Tibetan cultural issues website Chomei, according to the Dharamsala, India-based Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy. Kate Saunders, U.K. communications director for the International Campaign for Tibet, told CPJ by telephone from New Delhi that she learned of his arrest from two sources.

The detention appeared to be part of a wave of arrests of writers and intellectuals in advance of the 50th anniversary of the March 1959 uprising preceding the Dalai Lama’s departure from Tibet. The 2008 anniversary had provoked ethnic rioting in Tibetan areas, and international reporters were barred from the region.

In November 2009, a Gannan court sentenced Tsang to 15 years in prison for disclosing state secrets, according to The Associated Press.

Kunga Tsayang (Gang-Nyi), freelance

Imprisoned: March 17, 2009

The Public Security Bureau arrested Tsayang during a late-night raid, according to the Dharamsala, India-based Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, which said it had received the information from several sources.

An environmental activist and photographer who also wrote online articles under the penname Gang-Nyi (Sun of Snowland), Tsayang maintained his own website, Zindris (Jottings), and contributed to others. He wrote several essays on politics in Tibet, including “Who is the real instigator of protests?” according to the New York-based advocacy group Students for a Free Tibet.

Tsayang was convicted of revealing state secrets and sentenced in November 2010 to five years in prison, according to the center. Sentencing was imposed during a closed-court proceeding in the Tibetan area of Gannan, Gansu province.

A number of Tibetans, including journalists, were arrested around the March 10 anniversary of the failed uprising in 1959 that prompted the Dalai Lama’s departure from Tibet. Security measures were heightened in the region in the aftermath of ethnic rioting in March 2008.

Tan Zuoren, freelance

Imprisoned: March 28, 2009

Tan, an environmentalist and activist, had been investigating the deaths of schoolchildren killed in the May 2008 earthquake in Sichuan province when he was detained in Chengdu. Tan, believing that shoddy school construction contributed to the high death toll, had intended to publish the results of his investigation ahead of the first anniversary of the earthquake, according to international news reports.

Tan’s supporters believe he was detained because of his investigation, although the formal charges did not cite his earthquake reporting. Instead, he was charged with “inciting subversion” for writings posted on overseas websites that criticized the military crackdown on demonstrators at Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989.

In particular, authorities cited “1989: A Witness to the Final Beauty,” a firsthand account of the Tiananmen crackdown published on overseas websites in 2007, according to court documents. Several witnesses, including the prominent artist Ai Weiwei, were detained and blocked from testifying on Tan’s behalf at his August 2009 trial.

On February 9, 2010, Tan was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison, according to international news reports. On June 9, 2010, the Sichuan Provincial High People’s Court rejected his appeal. Tan’s wife, Wang Qinghua, told reporters in Hong Kong and overseas that he had contracted gout and was not receiving sufficient medical attention. Visitors were subject to strict examination before being allowed to see him, the German public news organization Deutsche Welle reported in 2012, citing Wang.

Memetjan Abdulla, freelance

Imprisoned: July 2009

Abdulla, editor of the state-run China National Radio’s Uighur service, was detained in July 2009 for allegedly instigating ethnic rioting in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region through postings on the Uighur-language website Salkin, which he managed in his spare time, according to international news reports. A court in the regional capital, Urumqi, sentenced him to life imprisonment on April 1, 2010, the reports said. The exact charges against Abdulla were not disclosed.

The U.S. government-funded Radio Free Asia (RFA) reported on the sentence in December 2010, citing an unnamed witness at the trial. Abdulla was targeted for talking to international journalists in Beijing about the riots, and translating articles on the Salkin website, RFA reported. The Germany-based World Uyghur Congress confirmed the sentence with sources in the region, according to The New York Times.

Tursunjan Hezim, Orkhun

Imprisoned: July 2009

Details of Hezim’s arrest following the 2009 ethnic unrest in northwestern Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region first emerged in March 2011. Police in Xinjiang detained international journalists and severely restricted Internet access for several months after rioting broke out on July 5, 2009, in Urumqi, the regional capital, between groups of Han Chinese and the predominantly Muslim Uighur minority.

The U.S. government-funded Radio Free Asia, citing an anonymous source, reported that a court in the region’s far western district of Aksu had sentenced Hezim, along with other journalists and dissidents, in July 2010. Several other Uighur website managers received heavy prison terms for posting articles and discussions about the previous year’s violence, according to CPJ research.

Hezim edited the well-known Uighur website Orkhun. U.S.-based Uighur scholar Erkin Sidick told CPJ that the editor’s whereabouts had been unknown from the time of the rioting until news of the conviction surfaced in 2011. Hezim was sentenced to seven years in prison on unknown charges in a trial closed to observers, according to Sidick, who had learned the news by telephone from sources in his native Aksu. Chinese authorities frequently restrict information on sensitive trials, particularly those involving ethnic minorities, according to CPJ research.

Gulmire Imin, freelance

Imprisoned: July 14, 2009

Imin was one of several administrators of Uighur-language Web forums who were arrested after the July 2009 riots in Urumqi, in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. In August 2010, Imin was sentenced to life in prison on charges of separatism, leaking state secrets, and organizing an illegal demonstration, a witness to her trial told the U.S. government-funded broadcaster Radio Free Asia (RFA).

Imin held a local government post in Urumqi. She also contributed poetry and short stories to the cultural website Salkin, and had been invited to moderate the site in late spring 2009, her husband, Behtiyar Omer, told CPJ. Omer confirmed the date of his wife’s initial detention in a broadcast statement given at the Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy in 2011.

Authorities accused Imin of being an organizer of major demonstrations on July 5, 2009, and of using the Uighur-language website to distribute information about the event, RFA reported. Imin had been critical of the government in her online writings, readers of the website told RFA. The website was shut down after the July riots and its contents were deleted.

Imin was also accused of leaking state secrets by phone to her husband, who lives in Norway. Her husband told CPJ that he had called her on July 5 only to be sure she was safe.

The riots, which began as a protest of the death of Uighur migrant workers in Guangdong province, turned violent and resulted in the deaths of 200 people, according to the official Chinese government count. Chinese authorities shut down the Internet in Xinjiang for months after the riots as hundreds of protesters were arrested, according to international human rights organizations and local and international media reports.

Nijat Azat, Shabnam

Nureli, Salkin

Imprisoned: July or August 2009

Authorities imprisoned Nureli, who goes by one name, and Azat in an apparent crackdown on managers of Uighur-language websites. Azat was sentenced to 10 years and Nureli to three years on charges of endangering state security, according to international news reports. The Uyghur American Association reported that the pair were tried and sentenced in July 2010.

Their sites, which have been shut down by the government, had run news articles and discussion groups concerning Uighur issues. The New York Times cited friends and family members of the men who said they were prosecuted because they had failed to respond quickly enough when they were ordered to delete content that discussed the difficulties of life in Xinjiang. Their whereabouts were unknown in late 2012.

Dilixiati Paerhati, Diyarim

Imprisoned: August 7, 2009

Paerhati, who edited the popular Uighur-language website Diyarim, was one of several online forum administrators arrested after ethnic violence in Urumqi in July 2009. Paerhati was sentenced to a five-year prison term in July 2010 on charges of “endangering state security,”F according to international news reports.

Paerhati was detained and interrogated about riots in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region on July 24, 2009, but was released without charge after eight days. Agents seized him from his apartment on August 7, 2009, although the government issued no formal notice of arrest, his U.K.-based brother, Dilimulati, told Amnesty International. News reports citing his brother said Paerhati was prosecuted for failing to comply with an official order to delete anti-government comments on the website.

Gheyrat Niyaz (Hailaite Niyazi), Uighurbiz

Imprisoned: October 1, 2009

Security officials arrested website manager Niyaz, sometimes referred to as Hailaite Niyazi, in his home in the regional capital, Urumqi, according to international news reports. He was convicted under sweeping charges of “endangering state security” and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

According to international media reports, Niyaz was punished because of an August 2, 2009, interview with Yazhou Zhoukan (Asia Weekly), a Chinese-language magazine based in Hong Kong. In the interview, Niyaz said authorities had not taken steps to prevent violence in the July 2009 ethnic unrest that broke out in China’s far-western Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region.

Niyaz, who once worked for the state newspapers Xinjiang Legal News and Xinjiang Economic Daily, also managed and edited the website Uighurbiz until June 2009. A statement posted on the website quoted Niyaz’s wife as saying that while he did give interviews to international media, he had no malicious intentions.

Authorities blamed local and international Uighur sites for fueling the violence between Uighurs and Han Chinese in the predominantly Muslim Xinjiang region. Uighurbiz founder Ilham Tohti was questioned about the contents of the site and detained for more than six weeks, according to international news reports.

Tashi Rabten, freelance

Imprisoned: April 6, 2010

Public security officials detained Rabten for publishing a banned magazine and a collection of articles, according to Phayul, a pro-Tibetan independence news website based in New Delhi.

Rabten, a student at Northwest Minorities University in Lanzhou, Gansu province, edited the magazine Shar Dungri (Eastern Snow Mountain) in the aftermath of ethnic rioting in Tibet in March 2008. The magazine was banned by local authorities, according to the International Campaign for Tibet. The journalist later self-published a collection of articles titled Written in Blood, saying in the introduction that “after an especially intense year of the usual soul-destroying events, something had to be said,” the campaign reported.

The book and the magazine discussed democracy and recent anti-China protests; the book was banned after he had distributed 400 copies, according to the U.S. government-funded Radio Free Asia (RFA). Rabten had already been detained once before, in 2009, according to international Tibetan rights groups and RFA.

A court in Aba prefecture, a predominantly Tibetan area of Sichuan province, sentenced him to four years in prison in a closed-door trial on June 2, 2011, according to RFA and the International Campaign for Tibet. RFA cited a family member saying he had been charged with separatism, although CPJ could not independently confirm the charge.

Dokru Tsultrim (Zhuori Cicheng), freelance

Imprisoned: May 24, 2010

Tsultrim, a monk at Ngaba Gomang Monastery in western Sichuan province, was detained in April 2009 in connection with alleged anti-government writings and articles in support of the Dalai Lama, according to the Dharamsala, India-based Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy and the International Campaign for Tibet. Released after a month in custody, he was detained again in May 2010, according to the Dharamsala, India-based Tibet Post International. No formal charges or trial proceedings were disclosed.

At the time of his 2010 arrest, security officials raided his room at the monastery, confiscated documents, and demanded his laptop, a relative told The Tibet Post International. He and a friend had planned to publish the writings of Tibetan youths detailing an April 2010 earthquake in Qinghai province, the relative said.

Tsultrim, originally from Qinghai province, which is on the Tibetan plateau, also managed a private Tibetan journal, Khawai Tsesok (Life of Snow), which ceased publication after his 2009 arrest, the center said.

“Zhuori Cicheng” is the Chinese transliteration of his name, according to Tashi Choephel Jamatsang at the center, who provided CPJ with details by email.

Kalsang Jinpa (Garmi) freelance

Imprisoned: June 19, 2010

Jangtse Donkho (Nyen, Rongke), freelance

Imprisoned: June 21, 2010

Buddha, freelance

Imprisoned: June 26, 2010

The three men, contributors to the banned Tibetan-language magazine Shar Dungri (Eastern Snow Mountain), were detained in Aba, a Tibetan area in southwestern Sichuan province, the U.S. government-funded Radio Free Asia (RFA) reported.

Donkho, an author and editor who wrote under the penname Nyen, meaning “Wild One,” was detained on June 21, 2010, RFA reported. The name on his official ID is Rongke, according to the International Campaign for Tibet. Many Tibetans use only one name.

Buddha, a practicing physician, was detained on June 26, 2010, at the hospital where he worked in the town of Aba. Kalsang Jinpa, who wrote under the penname Garmi, meaning “Blacksmith,” was detained on June 19, 2010, RFA reported, citing local sources.

On October 21, 2010, they were tried together in the Aba Intermediate Court on charges of inciting separatism that were based on articles they had written in the aftermath of the March 2008 ethnic rioting. RFA, citing an unnamed source in Tibet, reported that the court later sentenced Donkho and Buddha to four years’ imprisonment each and Kalsang Jinpa to three years. In January 2011, the broadcaster reported that the three had been put in Mian Yang jail near the Sichuan capital, Chengdu, where they were subjected to hard labor.

Shar Dungriwas a collection of essays published in July 2008 and distributed in western China before authorities banned the publication, according to the advocacy group International Campaign for Tibet, which translated the journal. The writers assailed Chinese human rights abuses against Tibetans, lamented a history of repression, and questioned official media accounts of the March 2008 unrest.

Buddha’s essay, “Hindsight and Reflection,” was presented as part of the prosecution, RFA reported. According to a translation of the essay by the International Campaign for Tibet, Buddha wrote: “If development means even the slightest difference between today’s standards and the living conditions of half a century ago, why the disparity between the pace of construction and progress in Tibet and in mainland China?”

The editor of Shar Dungri, Tashi Rabten, was also jailed in 2010.

Liu Xianbin, freelance

Imprisoned: June 28, 2010

A court in western Sichuan province sentenced Liu to 10 years in prison on charges of inciting subversion through articles published on overseas websites between April 2009 and February 2010, according to international news reports. One was titled “Constitutional Democracy for China: Escaping Eastern Autocracy,” according to the BBC.

The sentence was unusually harsh; inciting subversion normally carries a maximum five-year penalty, international news reports said. Liu also signed Liu Xiaobo’s pro-democracy Charter 08 petition. (Liu Xiaobo, who won the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize for his actions, is serving an 11-year term on the same charge.)

Police detained Liu Xianbin on June 28, 2010, according to the Washington-based prisoner rights group Laogai Foundation. He was sentenced in 2011 during a crackdown on bloggers and activists who sought to organize demonstrations inspired by uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa, according to CPJ research.

Liu spent more than two years in prison for involvement in the 1989 anti-government protests in Tiananmen Square. He later served 10 years of a 13-year prison sentence handed down in 1999 after he founded a branch of the China Democracy Party, according to The New York Times.

Gao Yingpu, freelance

Imprisoned: July 2010

Gao, a former journalist who had contributed to the Guangdong-based Asia Pacific Economic Times newspaper and other publications, was sentenced in a secret trial in 2010 to a three-year prison term for endangering state security in a blog entry criticizing disgraced Chongqing Communist Party Secretary Bo Xilai, according to the Hong Kong-based Chinese Human Rights Defenders. A family member confirmed the conviction for CPJ.

In a report published by the overseas Chinese-language website Boxun News, an unidentified former classmate of Gao said the journalist’s wife had signed a written promise not to publicize the case. As a result, Gao had no legal representation or ability to appeal, and his family and friends were told he was working in Iraq, according to Boxun. News of his situation emerged when an online appeal was published online in China on March 23, according to the U.S. government-funded Voice of America. The reports did not specify where Gao was being held.

Gao had criticized Bo Xilai’s notorious 2009 anti-corruption or “smash black” campaign, which targeted organized crime, in a personal blog hosted by the instant messaging company Tencent QQ, according to Boxun. Bo was fired in 2012 amid a corruption and murder scandal.At least 4,781 people were imprisoned in 10 months during Bo’s crackdown on gangs, including many who were wrongfully convicted, according to The New York Times.

Lü Jiaping, freelance

Imprisoned: September 4, 2010

Jin Andi, freelance

Imprisoned: September 19, 2010

Beijing police detained Lü, a military scholar in his 70s, his wife, Yu Junyi, and a colleague, Jin , for inciting subversion in 13 online articles they wrote and distributed together, according to international news reports and human rights groups.

A court sentenced Lü to 10 years in prison and Jin to eight years in prison on May 13, 2011, according to the Hong Kong-based advocacy group Chinese Human Rights Defenders. Yu, 71, was given a suspended three-year sentence and kept under residential surveillance, according to the group. Their families were not informed of the trial, and Yu broke the news when the surveillance was lifted in February 2012, according to the English-language Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post and the U.S. government-funded Voice of America.

An appeals court upheld the sentences on the basis that the three defendants “wrote essays of an inciting nature” and “distributed them through the mail, emails, and by posting them on individuals’ web pages. [They] subsequently were posted and viewed by others on websites such as Boxun News and New Century News,” according to a 2012 translation of the appeal verdict published online by William Farris, a Beijing-based lawyer. The 13 offending articles, which were principally written by Lü, were listed in the appeal judgment along with dates, places of publication, and number of times they were re-posted. One 70-word paragraph was re-produced as proof of incitement to subvert the state. The paragraph said in part that the Chinese Communist Party’s status as a “governing power and leadership utility has long-since been smashed and subverted by the powers that hold the Party at gunpoint.”

Court documents said Lü and Jin were being held in the Beijing Number 1 Detention Center. Lü suffered a heart attack in jail, as well as other health problems, leaving him barely able to walk, according to Chinese Human Rights Defenders.

Li Tie, freelance

Imprisoned: September 15, 2010

Police in Wuhan, Hubei province, detained 52-year-old freelancer Li, according to international news reports. The Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court tried him behind closed doors on April 18, 2011, but did not announce the verdict until January 18, 2012, when he was handed a 10-year prison term and three additional years’ political deprivation, according to news reports citing Li’s lawyer. Only Li’s mother and daughter were allowed to attend the trial, news reports said.

The court cited 13 of Li’s online articles to support the charge of subversion of state power, a more serious count than inciting subversion, which is a common criminal charge used against jailed journalists in China, according to CPJ research. Evidence in the trial cited articles including one headlined “Human beings’ heaven is human dignity,” in which Li urged respect for ordinary citizens and called for democracy and political reform, according to international news reports. Prosecutors argued that the articles proved Li had “anti-government thoughts” that would ultimately lead to “anti-government actions,” according to Hong Kong-based Chinese Human Rights Defenders.

Jian Guanghong, a lawyer hired by his family, was detained before the trial, and a government-appointed lawyer represented Li instead, according to the group. Prosecutors also cited Li’s membership in the small opposition group the China Social Democracy Party, the group reported.

Jolep Dawa, Durab Kyi Nga

Imprisoned: October 1, 2010

A court in Aba in southwestern Sichuan province sentenced Dawa, a Tibetan writer and editor, to three years in prison in October 2011, according to the U.S. government-funded Radio Free Asia and the India-based Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy.

Dawa, who is also a teacher, edited Durab Kyi Nga, a monthly Tibetan-language magazine, according to the broadcaster and the rights group. He had been held in detention without trial since October 2010, the organizations said. The exact date of the sentencing was not reported, and the charges against the writer were not disclosed.

Chen Wei, freelance

Imprisoned: February 20, 2011

Police in Suining, Sichuan, detained Chen among the dozens of lawyers, writers, and activists jailed nationwide following anonymous online calls for a nonviolent “Jasmine Revolution” in China, according to international news reports. The Hong Kong-based Chinese Human Rights Defenders reported that Chen was formally charged on March 28, 2011, with inciting subversion of state power.

Chen’s lawyer, Zheng Jianwei, made repeated attempts to visit him but was not allowed access until September 8, 2011, according to the rights group and the U.S. government-funded broadcaster Radio Free Asia. RFA reported that police had selected four pro-democracy articles Chen had written for overseas websites as the basis for criminal prosecution. In December 2011, a court in Suining sentenced Chen to nine years in prison on charges of “inciting subversion,” a term viewed as unusually harsh.

Chinese Human Rights Defenders reported that at least two other activists remained in criminal detention for transmitting information online related to the “Jasmine Revolution.” Chen’s case, however, was the only one linked in public reports to independent journalistic writing.

Chen, a student protester during the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident, had been imprisoned twice before for democracy activism, according to Chinese Human Rights Defenders. Sichuan police blocked Chen’s wife from visiting him in January 2012, according to Radio Free Asia.

Choepa Lugyal (Meycheh), freelance

Imprisoned: October 19, 2011

Security officials detained Lugyal, a publishing house employee who wrote online under the name Meycheh, at his home in Gansu province, according to the Beijing-based Tibetan commentator Woeser and the Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, which is based in India. Lugyal had written several print and online articles, including pieces for the Tibetan magazine Shar Dungri, according to the center. Authorities disclosed neither the charges against him nor his whereabouts.

Chinese authorities banned Shar Dungri, which was published in the aftermath of 2008 ethnic unrest between Tibetans and Han Chinese, and jailed several contributors, including Buddha, Jangtse Donkho, and Kalsang Jinpa. Editor Tashi Rabten was sentenced in July 2011 to four years in prison on charges described by family members as separatism-related.

Chen Xi, freelance

Imprisoned: November 29, 2011

A court in Guiyang, Guizhou province, sentenced Chen to 10 years in prison followed by three years’ deprivation of political rights on December 26, 2011, on charges of inciting subversion against state power based on online writings. The sentencing took place just four days after writer Chen Wei was sentenced to nine years on the same charge in Sichuan province.

Chen Xi was originally detained in November 2011 for campaigning for independent local People’s Congress candidates, according to the U.K.’s Guardian and other news reports. However, during his trial, the prosecution cited 36 articles Chen had written and published online to support the charges against him, according to international news reports. The reports did not specify which websites published the articles. “[He] was calling for democracy and human rights. This wish was his whole crime,” Chen’s wife, Zhang Qunxuan, told the New York-based advocacy group Human Rights in China.

Chen had been imprisoned twice in the past for political activism, including his activities during the 1989 student movement. He also was a signatory of imprisoned writer Liu Xiaobo’s Charter 08, according to the reports.

Dawa Dorje, freelance

Imprisoned: February 3, 2012

Police detained writer and government researcher Dorje at the airport in Lhasa, capital of the Tibetan Autonomous Region, where he had traveled for a conference on preserving Tibetan culture, according to exiled Tibetan groups and international news reports.

Dorje, who worked for the Nierong county government in western Sichuan province, kept a blog that is no longer accessible and was known for writing poems, books, and essays on the Tibetan language, including the article “Nationality and Language,” according to Dechen Pemba, editor of the High Peaks Pure Earth website, which translates articles from Tibetan writers. Dorje also wrote about democracy and human rights, according to the news reports.

Dorje was one of several high-profile cultural figures, including singers, performers, and writers, detained in early 2012 in an apparent crackdown on advocates of Tibetan-language culture. Chinese authorities have not confirmed his whereabouts or the basis for his detention.

Gangkye Drubpa Kyab, Hada

Imprisoned: February 15, 2012

Police in western Sichuan province detained Kyab, a Tibetan teacher, writer, and editor, in his Serthar county home, according to international news reports. The reason for the arrest was not clear, and police would not produce documentation when his wife asked to see a warrant, the reports said. The detention took place amid a round-up of prominent Tibetan cultural figures in 2012, including singers, authors, and performers, according to international news reports.

Kyab was a well-known author and essayist, according to Invisible Tibet, a blog published by the Beijing-based Tibetan writer Woeser. He also edited the Tibetan-language magazine Hada,Radio Free Asia and the BBC Chinese service reported. CPJ could not independently confirm his whereabouts or the charges he faced.

“He wrote a lot of articles and books about the environment, Tibetan culture, everything. He wrote about the news,” Switzerland-based Tibetan activist Jamyang Tsering told CPJ by telephone. “He was arrested because of what he wrote.”

Cuba: 1

Calixto Ramón Martínez Arias, Centro de Información Hablemos Press

Imprisoned: September 16, 2012

State security agents arrested Martínez Arias near José Martí International Airport in Havana where he was reporting on two tons of medicine and medical equipment that had been damaged, according to CPJ sources and news reports. Martínez Arias, a reporter with the independent news agency Centro de Información Hablemos Press, was taken to a police station in Havana where he was interrogated and beaten, Roberto de Jesús Guerra Pérez, the organization’s director, told CPJ.

According to Guerra Pérez, Martínez Arias was accused of contempt under Cuba’s archaic desacato or disrespect laws for shouting anti-Castro slogans after he was harassed by authorities. Article 144.1 of the Cuban criminal code establishes that those who threaten, defame, insult, or offend the dignity of a public official can be jailed for up to three years.

On September 27, Martínez Arias was transferred to the Valle Grande Prison in the town of La Lisa, Havana province, Guerra Pérez told CPJ. The journalist began a hunger strike in November, according to Hablemos Press. Two people recently released from jail told Hablemos Press that Martínez Arias had been placed in solitary confinement.

At the time of his arrest Martínez Arias was looking into reasons why a shipment of medicine and medical equipment reportedly donated by the World Health Organization had been left to go bad, according to Guerra Pérez and news reports.

Martínez Arias, who has worked for the news agency since 2009, has reported on sensitive issues such as an outbreak of cholera in Granma province, according to CPJ sources and news reports. Prominent human rights activist Elizardo Sánchez Santa Cruz, president of the Cuban Commission on Human Rights and National Reconciliation in Havana, told CPJ that Martínez Arias was arrested for his journalistic work.

Martínez Arias has often been harassed by authorities for his reporting, Guerra Pérez said. In 2011, CPJ documented a string of arrests of journalists from Centro de Información Hablemos Press, which prevented them from reporting on the Communist Party Congress.

Democratic Republic of Congo: 3

Pierre Sosthène Kambidi, Christian Radio Télévision Chrétienne

Imprisoned: August 28, 2012

Agents of the Congolese national intelligence agency arrested Kambidi, editor-in-chief of Christian Radio Télévision Chrétienne, or RTC, in the central town of Kananga, according to local press freedom group Journaliste En Danger. Kambidi was being held without charge in late year, according to news reports.

Kambidi and another RTC journalist had received death threats in connection with a news program that aired August 16, RTC Director Charles Boniface Bayakwabo told Journaliste En Danger. During the program, a local opposition politician suggested that President Joseph Kabila’s regime was nearing an end. The politician was reacting to the station’s rebroadcast of an interview conducted by UN-backed Radio Okapi with John Tshibangu, an army officer turned rebel, according to news reports. In the interview, Tshibangu announced the creation of an armed rebel movement.

Kambidi was transferred to the capital, Kinshasa, on August 30, Bayakwabo said.

Dadou Ekiom, Télé 50

Guy Ngiaba, Kimpangi

Imprisoned: November 27, 2012

The public prosecutor in the city of Bandundu, northeast of the capital Kinshasa, placed Ekiom and Ngiaba under arrest on criminal defamation charges based on a complaint filed by Boniface Ntwa, speaker of the provincial assembly, according to the the local press freedom group Observatoire de la Liberte de la Presse En Afrique .

The charges were based on November 2 commentary that Ekiom and Ngiaba aired as presenters and producers of the talk show “Référendum” on the local broadcaster Nzondo Télévision, the station’s news director, Natanaël Kadima, told CPJ. The journalists had commented on alleged attempts by some members of the provincial assembly to oust the speaker, Kadima said.

Ekiom is local correspondent for the Kinshasa-based private broadcasters Télé 50, and Ngiaba works for the weekly Kimpangi, also based in the capital, according to OLPA.

Both journalists were held in pre-trial detention at Bandudu’s central prison known as Cinquantennaire.

Eritrea: 28

Said Abdelkader, Admas

Yusuf Mohamed Ali, Tsigenay

Amanuel Asrat, Zemen

Temesgen Ghebreyesus, Keste Debena

Mattewos Habteab, Meqaleh

Dawit Habtemichael, Meqaleh

Medhanie Haile, Keste Debena

Seyoum Tsehaye, Setit

Imprisoned: September 2001

More than 10 years after imprisoning several editors of Eritrea’s once-vibrant independent press and banning their publications to silence growing criticism of President Isaias Afewerki, Eritrean authorities had yet to account for the whereabouts, health, or legal status of the journalists, some of whom may have died in secret detention.

The journalists were arrested without charge after the government suddenly announced on September 18, 2001, that it was closing the country’s independent newspapers. The papers had reported on divisions within the ruling Party for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) and advocated for full implementation of the country’s constitution. A dozen top officials and PFDJ reformers, whose pro-democracy statements had been covered by the independent newspapers, were also arrested.

Authorities initially held the journalists at a police station in the capital, Asmara, where they began a hunger strike on March 31, 2002, and smuggled a message out of jail demanding due process. The government responded by transferring them to secret locations without ever bringing them before a court or publicly registering charges.

Over the years, Eritrean officials have offered vague and inconsistent explanations for the arrests-from anti-state conspiracies involving foreign intelligence to accusations of skirting military service to violating press regulations. Officials at times have even denied that the journalists existed. Meanwhile, shreds of often unverifiable, second- or third-hand information smuggled out of the country by people fleeing into exile have suggested the deaths of as many as five journalists in custody. Several CPJ sources said the journalists were confined at the Eiraeiro prison camp or at a military prison, Adi Abeito, based in Asmara.

In February 2007, CPJ established that one detainee, Fesshaye “Joshua” Yohannes, a co-founder of the newspaper Setit and a 2002 recipient of CPJ’s International Press Freedom Award, had died in custody at the age of 47.

CPJ is seeking corroboration of reports that several other detainees may have died in custody. In August 2012, the international press freedom group Reporters Without Borders, citing a former prison guard, said Dawit Habtemichael and Mattewos Habteab had died at Eiraeiro in recent years. In 2010, the Ethiopian government-sponsored Radio Wegahta also cited a former Eritrean prison guard as saying that Habteab had died at Eiraeiro.

An unbylined report on the Ethiopian pro-government website Aigaforum in August 2006 quoted 14 purported Eiraeiro guards as citing the deaths of prisoners whose names closely resembled Yusuf Mohamed Ali, Medhanie Haile, and Said Abdelkader. The details could not be independently confirmed, although CPJ sources considered it to be generally credible. In 2009, the London-based Eritrean opposition news site Assena posted purportedly leaked death certificates of Fesshaye, Yusuf, Medhanie, and Said.

CPJ lists the journalists on the 2012 prison census as a means of holding the government accountable for their fates. Relatives of the journalists also told CPJ that they maintain hope their loved ones are still alive.

Dawit Isaac, Setit

Imprisoned: September 23, 2001

The imprisonment of Dawit, co-founder of the banned newspaper Setit, has drawn international attention. Dawit, who has dual Eritrean and Swedish citizenship, has been held incommunicado and without charge since 2001, except for brief contact with his family in 2005.

A government crackdown on the independent press in 2001 led to the imprisonment without charge of numerous prominent journalists. Eritrean President Isaias Afewerki’s administration has refused to account for the whereabouts, legal status, or health of the jailed journalists. When asked about Dawit’s crime in a May 2009 interview with Swedish freelance journalist Donald Boström, Afewerki declared, “I don’t know,” but said the journalist had made “a big mistake,” without offering details. In August 2010, Yemane Gebreab, a senior presidential adviser, said in an interview with Swedish daily Aftonbladet that Dawit was being held for “very serious crimes regarding Eritrea’s national security and survival as an independent state.”

In July 2011, Dawit’s brother, Esayas, and three jurists-Jesús Alcalá, Prisca Orsonneau, and Percy Bratt-filed a writ of habeas corpus with Eritrea’s Supreme Court. The writ called for information on Dawit’s whereabouts and a review of his detention. In March 2012, the Supreme Court of Eritrea confirmed that it had received the petition.

In September 2011, the European Parliament adopted a resolution expressing “fears for the life” of Dawit, calling for his release and urging the European Council to consider targeted sanctions against Eritrean officials.

Hamid Mohammed Said, Eri-TV

Imprisoned: February 15, 2002

Hamid, a reporter for the Arabic-language service of the government-controlled broadcaster Eri-TV was arrested without charge in connection with the government’s crackdown on the independent press, which began in September 2001, according to CPJ sources.

In a July 2002 fact-finding mission to Asmara, the capital, a CPJ delegation learned from local sources that Hamid was among three state media reporters arrested. Two of the journalists, Saadia Ahmed and Saleh Aljezeeri, were later released, but Hamid was being held in an undisclosed location, CPJ was told.

The government has refused to respond to numerous inquiries from CPJ and other international organizations seeking information about Said’s whereabouts, health, and legal status.

While the government’s motivation in imprisoning journalists is unknown in most cases, CPJ research has found that state media journalists work in a climate of intimidation, retaliation, and absolute control. In this context of extreme repression, CPJ considers journalists attempting to escape the country or in contact with third parties abroad as struggling for press freedom.

Ismail Abdelkader, Radio Bana

Ghirmai Abraham, Radio Bana

Issak Abraham, Radio Bana

Mohammed Dafla, Radio Bana

Araya Defoch, Radio Bana

Simon Elias, Radio Bana

Yirgalem Fesseha, Radio Bana

Biniam Ghirmay, Radio Bana

Mulubruhan Habtegebriel, Radio Bana

Bereket Misguina, Radio Bana

Mohammed Said Mohammed, Radio Bana

Meles Nguse, Radio Bana

Imprisoned: February 19, 2009

Security forces raided government-controlled Radio Bana in February 2009 and arrested its entire staff, according to a U.S. diplomatic cable disclosed by WikiLeaks in November 2010.

The cable, sent by then-U.S. Ambassador Ronald McMullen and dated February 23, 2009, attributed the information to the deputy head of mission of the British Embassy in Asmara in connection with the detention of a British national who volunteered at the station. According to the cable, the volunteer reported being taken by security forces with the Radio Bana staff to an unknown location six miles (10 kilometers) north of the capital and later being separated from them. The volunteer was not interrogated and was released the next day. According to the cable, some of the station’s staff members were released as well.

CPJ sources said that at least 12 journalists working for Radio Bana had been held incommunicado since the raid. The reasons for the detentions were unclear, but CPJ sources said the journalists were either accused of providing technical assistance to two opposition radio stations broadcasting into the country from Ethiopia, or of participating in a meeting in which detained journalist Meles Nguse spoke against the government. The staff’s close collaboration with two British nationals on the production of educational programs may have also led to their arrests, according to the same sources.

Several of the detainees had worked for other state media outlets before beginning stints at Radio Bana, a station sponsored by the Education Ministry. Ghirmai was the producer of an arts program with government-controlled state radio Dimtsi Hafash, and Issak had produced a Sunday entertainment show on the same station. Issak and Mulubruhan, a reporter with state daily Haddas Erta, had also co-authored a book of comedy. Bereket (also a film director and scriptwriter), Meles (also a poet), and Yirgalem(a poet as well) were columnists for Haddas Erta. CPJ had identified one of the detainees as Esmail Abd-el-Kader in a previous survey. Further research indicated his name is more commonly spelled Ismail Abdelkader.

Authorities have not responded to numerous inquiries from CPJ and other international groups seeking information about the detainees’ whereabouts, health, and legal status.

Habtemariam Negassi, Eri-TV

Imprisoned: January or February 2009

Authorities arrested Habtemariam , a veteran cameraman and head of the English desk at the government-controlled broadcaster Eri-TV, according to CPJ sources. No reason was given for the arrest and no formal charges were publicly disclosed.

Authorities have not responded to numerous inquiries from CPJ seeking information about Habtemariam’s whereabouts, health, and legal status. While the government’s motivation in imprisoning journalists is unknown in most cases, CPJ research has found that state media journalists work in a climate of intimidation, retaliation, and absolute control. In this context of extreme repression, CPJ considers journalists attempting to escape the country or in contact with third parties abroad as struggling for press freedom.

Sitaneyesus Tsigeyohannes, Eritrean Profile

Imprisoned: August 2009

Two men believed to be government agents took Sitaneyesus into custody at the offices of the government-controlled English-language weekly Eritrean Profile, two CPJ sources said.

The agents said Sitaneyesus, a staff reporter for the paper, was being brought in for questioning, but the journalist had not been seen since, according to the CPJ sources. Sitaneyesus was also active in the Pentecostal Church, which is banned in Eritrea.

Nebiel Edris, Dimtsi Hafash

Eyob Kessete, Dimtsi Hafash

Mohamed Osman, Dimtsi Hafash

Ahmed Usman, Dimtsi Hafash

Imprisoned: February and March 2011

Several journalists working for the government-controlled radio station were arrested in early 2011, according to CPJ sources. Authorities did not disclose the basis of the arrests, although CPJ sources said at least one of the journalists, Eyob, was arrested on allegations that he had helped others flee the country.

The four reporters worked for different arms of Dimtsi Hafash: Nebiel for the Arabic-language service; Ahmed for the Tigrayan-language service, Mohamed for the Bilen-language service, and Eyob for the Amharic-language service.

Tesfalident Mebrahtu, a prominent sports journalist with Dimtsi Hafash and Eri-TV, was arrested at the same time on allegations that he was attempting to flee the country. CPJ sources said he had recently been freed and allowed to resume work.

While the government’s motivation in imprisoning journalists is unknown in most cases, CPJ research has found that state media journalists work in a climate of intimidation, retaliation, and absolute control. In this context of extreme repression, CPJ considers journalists attempting to escape the country or in contact with third parties abroad as struggling for press freedom.

Ethiopia: 6

Saleh Idris Gama, Eri-TV

Tesfalidet Kidane Tesfazghi, Eri-TV

Imprisoned: December 2006

Tesfalidet, a producer for Eritrea’s state broadcaster Eri-TV, and Saleh, a cameraman, were arrested in late 2006 on the Kenya-Somalia border during Ethiopia’s invasion of southern Somalia.

The Ethiopian Foreign Ministry first disclosed the detention of the journalists in April 2007, and presented them on state television as part of a group of 41 captured terrorism suspects, according to CPJ research. Though Eritrea often conscripted journalists into military service, the video did not present any evidence linking the journalists to military activity. The ministry pledged to subject some of the suspects to military trials but did not identify them by name. In a September 2011 press conference with exiled Eritrean journalists in Addis Ababa, then-Prime Minister Meles Zenawi said Saleh and Tesfalidet would be freed if investigations determined they were not involved in espionage, according to news reports and journalists who participated in the press conference.

But Tesfalidet and Saleh had not been tried by late 2012, and authorities disclosed no information about legal proceedings against them, according to local journalists. Authorities have also not disclosed any information about the detainees’ well-being and whereabouts.

Reeyot Alemu, freelance

Imprisoned: June 21, 2011