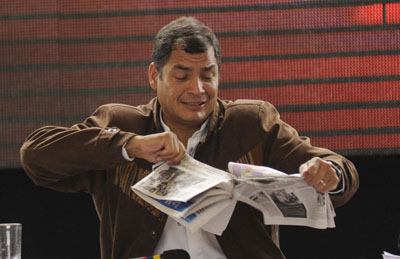

Rafael Correa’s administration has led Ecuador into a new era of widespread repression by pre-empting private news broadcasts, enacting restrictive legal measures, smearing critics, and filing debilitating defamation lawsuits. A CPJ special report by Carlos Lauría

Jeanette Hinostroza, anchor of the Teleamazonas newsmagazine “30 Plus” and regular critic of President Rafael Correa, knew she had more fodder for her commentary when she learned in April that a woman had been charged with disrespecting the two-term Ecuadoran leader. Correa had abused his authority and demeaned his office, Hinostroza told viewers, by ordering the woman’s arrest based on what he considered to be an insulting gesture.

It wasn’t long before Hinostroza found herself in the crosshairs of Correa, a president who freely calls reporters “ignorant” and “liars.” The next day, the Correa administration ordered Teleamazonas, a Quito-based private network known for its criticism of the president’s policies, to pre-empt 10 minutes of Hinostroza’s program with a harsh and personal rebuttal from a government spokesman who called her ethics into question. That Saturday, during his weekly address on state radio, Correa went on to question Hinostroza’s intellect, mocking her as a “redhead” who should be ignored. Teleamazonas is a favorite target of the administration, having been ordered off the air for three days in 2009 after running a story about the effect of natural gas exploration on the local fishing industry. But Teleamazonas is hardly alone.

More in this report

• CPJ’s recommendations

• Video report

In print

• Download the pdf

In other languages

• Español

Correa, a 48-year-old left-leaning economist, brooks no dissent from the news media and, in less than five years, has turned Ecuador into one of the hemisphere’s most restrictive nations for the press. Promising a “citizens’ revolution” that would boost revenue from the country’s natural resources, Correa took office in January 2007 with substantial support from mainstream news media. But after vowing to fight what he called Ecuador’s corrupt elite, he took an aggressively adversarial stance against news media, which threatens the internationally guaranteed free expression rights of all of his citizens.

As it did in the Hinostroza case, the Correa administration has repeatedly forced individual broadcasters to air lengthy government rebuttals to critical news reports, thus supplanting independent viewpoints with its own. On hundreds of other occasions, the administration has pre-empted all broadcast programming nationwide for presidential addresses known as cadenas, which, though traditionally used to deliver information in times of crisis, have become a forum for political confrontation. This coerced pre-emption is part of an alarming record of official censorship and anti-press harassment that also includes the use of defamation laws to silence critics, smear campaigns to discredit them, and ballot measures to regulate news content and media ownership, a CPJ investigation has found. At the same time, the government has built one of the region’s most extensive state media operations, a network of more than 15 television, radio, and print outlets that serves largely as a presidential megaphone.

High-ranking members of the Correa administration did not respond to CPJ’s requests to meet with its representatives during an April fact-finding mission, and did not respond to subsequent requests for comment.

Defamation cases as retaliatory tools

Local press freedom advocates are deeply concerned. “It has become difficult for the press to work free of government interference. Official harassment of critical reporters has increased substantially,” said César Ricaurte, executive director of the Andean Foundation for Media Observation & Study, known as Fundamedios, which has documented more than 380 free press violations from January 2008 through July 2011. From 22 documented cases in 2008, abuses spiraled to 151 in 2010 and are on pace to far exceed that level this year, according to the group.

Correa has led the way in filing debilitating defamation complaints against independent journalists. In March, he brought a criminal complaint against three executives and an editor of the Guayaquil-based newspaper El Universo in connection with an opinion piece that referred to him as “the dictator.” The author, opinion editor Emilio Palacio, alleged that Correa had ordered troops to fire “without warning on a hospital full of civilians and innocent people” during a violent labor standoff with national police in September 2010. (Angered by planned pay cuts, rebellious police officers effectively barricaded Correa in the hospital for about 12 hours, prompting the government to summon troops to the scene. The nationwide police protests—which led to three fatalities, dozens of injuries, and the shutdown of airports and highways—also marked a low point in government restrictions on the news media. The communications secretary ordered broadcasters to halt their own news reports and carry only state news programming for about six hours during the height of the crisis.)

Shortly before the defamation trial began, Palacio stepped down from El Universo in hopes that his resignation would prompt Correa to withdraw his complaint. As the trial commenced in July, the daily’s directors said the paper would print a correction and invited the president to write it himself. Correa rejected the idea. Less than 24 hours after the trial started, a Guayaquil judge issued a decision that would send the four defendants to jail for three years each and have them and El Universo pay a total of $40 million in damages. All four appealed the decision. So did Correa, who wanted $80 million in damages, although he claimed he would use the money to support Yasuni National Park.

CPJ research shows that other Ecuadoran officials have followed the president’s lead in using the country’s outdated criminal defamation provisions to retaliate against critical journalists. In the northern city of Esmeraldas, radio journalist Walter Vite Benítez was sentenced in May to a year in prison on criminal defamation charges related to his critical comments about a local mayor’s performance. (A subsequent court decision led to Vite’s release, although the narrow ruling found only that the statute of limitations had expired.) In 2008, provincial journalists Freddy Aponte Aponte and Milton Nelson Chacaguasay Flores were jailed on criminal defamation charges related to critical comments about local officials. In a region where imprisonment of journalists has been rare outside of Cuba, the recent criminal prosecutions have been striking.

Ecuador’s criminal defamation laws run counter to the emerging consensus in Latin America that civil remedies provide adequate redress in cases of alleged libel or slander. In December 2009, the Costa Rican Supreme Court eliminated prison terms for criminal defamation. One month earlier, in November 2009, the Argentine Congress repealed criminal defamation provisions as they pertain to matters of public interest. And in April 2009, Brazil’s Supreme Federal Tribunal voided the 1967 Press Law, a measure that had imposed harsh penalties for libel and slander. Regional precedent also holds that public officials should not enjoy protection from public scrutiny. “Public officials are subject to greater scrutiny by society,” states the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression, adopted by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2000. “Laws that penalize offensive expressions directed at public officials restrict freedom of expression and the right to information.”

The president has used civil avenues as well, pressing a $10 million defamation lawsuit against investigative journalists Juan Carlos Calderón and Christian Zurita, authors of the book El Gran Hermano (The Big Brother), which details allegations of official corruption. The investigation, first published in a six-part 2009 series in the Quito-based daily Expreso, alleged that companies belonging to Fabricio Correa, the president’s older brother, had obtained $600 million in state contracts, largely for road construction. Ecuadoran law bars presidential family members from using their relationships for economic gain. Although President Correa canceled the contracts and said he was unaware of the arrangements, he was so angered by the investigation that he devoted three cadenas to discrediting the book and its authors.

Calderón, an editor with the Quito-based weekly Vanguardia, and Zurita, a reporter for Expreso, are straining under the financial and professional costs imposed by the suit, which remains pending. Likening himself and his colleague to struggling boxers, Zurita said, “We have our backs against the ropes to see how we are going to defend ourselves.” With possible damages of such magnitude, they say, the lawsuit is creating a chilling effect on the Ecuadoran media and its ability to report on corruption and government transparency. “Official intimidation is fostering a climate of self-censorship among some media and colleagues,” Calderón told CPJ. “Some media are not covering and following accusations of official corruption made by the political opposition.”

A state of repression

Over the course of Correa’s tenure, the administration has created an elaborate legal framework to restrict news media. In a May referendum, voters approved by close margins a series of administration-backed ballot questions that strengthened executive branch powers, including two measures that harm press freedom.

The first question—posed with the prejudicial explanation that “media excesses” needed to be curbed—asked Ecuadorans to approve in concept a communications law that would, in turn, create a media regulatory council. The precise text of the law must be approved by the National Assembly, which is now debating the bill. But the proposed provisions are ominous. Article 11, for instance, would forbid “the use of violent, bloody, and death-related images” in news coverage deemed to have insufficient context, and the new regulatory council would be authorized, among its many proposed powers, to make that contextual determination. Under the proposal, the council would regulate radio, television, and print content in broad and vaguely defined areas such as violence, sex, and discrimination, unilaterally setting penalties for violations. The council’s independence appears questionable since five of its seven members would either be appointed by the executive branch or be chosen from groups with close ties to the executive.

Although Correa’s Alianza País party controls the assembly, lawmakers have resisted repressive press measures in the past, rejecting the president’s 2010 effort to enact a restrictive communications law. Now, though, with the weight of the referendum behind the measure, the administration appears able to leverage the bill’s passage.

The other ballot measure bars “private national media companies, executives, and main shareholders from holding assets in other companies.” Principals in media companies must divest within two years under the provision, which still requires enabling legislation. Journalists and free press advocates said the measure is intended to weaken the finances of media that oppose government policies. The Ecuadorian Association of Newspaper Editors has already challenged the provision in the country’s constitutional court, arguing that it contradicts existing constitutional guarantees. The ballot measure constitutes “the elimination of fundamental rights for media companies, their directors, and shareholders,” said Diego Cornejo, president of the editors group. It also appears to run counter to free expression guarantees enshrined in Article 13 of the American Convention on Human Rights, CPJ’s analysis found.

Supporters of the measure said it would democratize the media. In published interviews, Communications Secretary Fernando Alvarado said the legislation would promote diversity in the press.

A confrontational approach

Correa insists he’s fighting irresponsible journalism exercised by a small, elite group of media owners who hold too much power and are bent on toppling him to further their economic interests. His up-by-the-bootstraps background offers some insight into his press policies.

Born in 1963 in Guayaquil, an industrial port and Ecuador’s largest city, Correa endured a difficult childhood. His father, an entrepreneur, was arrested on charges of trying to smuggle cocaine into the United States and spent three years in an Atlanta prison in the late 1960s, according to news reports. But Correa flourished in academia, studying in the United States and Europe and earning a doctorate in economics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He was appointed finance minister in April 2005 but was forced to resign four months later when he failed to consult President Alfredo Palacio before publicly blasting the World Bank for denying Ecuador a loan.

When Correa took office as president in 2007, he became the latest of several leftist leaders who came to power in the region by running against traditional elites and the free-market policies of the United States. He moved quickly to strengthen his powers, winning voter approval for a special assembly to rewrite the constitution. The revised constitution, which took effect in 2008, allowed him to seek re-election through 2017 and broadened executive powers over the legislative and judicial branches along with economic policy.

Press freedom advocates were especially concerned about two other provisions in the 2008 constitutional revision. Article 19 introduced the concept of government intervention in news media, saying, “The law will regulate the prevalence of informational, educational, and cultural content in the media’s programming and will promote the creation of spaces for national and independent producers.” Article 18 stated that all individuals have the right to “find, receive, exchange, produce, and release truthful, verified, timely, contextualized, and plural information without censorship.” The text’s emphasis on “truthful, verified” information opened the door to official restrictions on information that the government disputed.

Yet another provision, Article 312, barred bankers from owning media companies. Media analysts said the prohibition was aimed at weakening Teleamazonas. By September 2010, station owner Fidel Egas, a principal in Pichincha Bank, sold his ownership stake to local, Peruvian, and Spanish investors. Anchor Jorge Ortiz, who hosted the critical talk show “La Hora de Jorge Ortiz,” resigned from the network a month before the sale was completed, saying he didn’t want to stand in the way of the acquisition, which needed government authorization.

Historically, Ecuadoran broadcast media had been controlled by powerful banking groups with close ties to politicians and political power bases, CPJ research shows. Some broadcasters were criticized, even within the profession, for not vigorously investigating the banking crisis that caused the collapse of several financial institutions in 2000 and cost taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars. But today’s media landscape is generally diverse and vibrant, CPJ research shows. Radio and television have large audiences, especially in the metropolitan areas of Quito and Guayaquil. Hundreds of radio stations operate around the country, among them numerous community and indigenous broadcasters in provincial regions. Five private television networks—Ecuavisa, Teleamazonas, RTS, Telerama, and Canal Uno—and more than 35 daily newspapers offer a wide range of opinions, analyses, and political perspectives, CPJ analysis found.

Yet Correa continues to beat a drum against media owners. In May, he used a cadena to criticize media companies for having interests in other businesses, including real estate, tourism, and insurance, and asserted that diverse holdings pose inherent conflicts of interests. “Many of these companies have policies directed to other businesses, commercial and private, in the name of freedom of expression,” Correa said.

State media as political megaphone

When Correa took office in 2007, state media consisted of a single radio network, Radio Nacional de Ecuador. In a remarkably short time, he has erected an extensive state media operation.

The foundation was built in large part on a 2008 government takeover of two private television stations, TC Televisión and Gama TV, and several other media outlets owned by Grupo Isaías, whose principals, Roberto and William Isaías, allegedly owed $661 million to Ecuador after the 1998 collapse of their banking institution, Filanbanco. The government takeover encompassed nearly 200 other businesses, but the television stations were especially valuable since they drew nearly 40 percent of the country’s news audience. At the time, Correa promised that his administration would sell the media assets to recover money owed to Ecuadorans. “He never fulfilled his promise,” said Tania Tinoco, a prominent anchor with the privately owned television station Ecuavisa. “Something similar happened with his pledge to preserve the media’s editorial line. All those outlets are used for government propaganda.”

In the next three years, the administration continued investing heavily in state media—the exact amount has not been disclosed—as it built an operation that now consists of several TV stations (TC Televisión, Gama TV, and Ecuador TV, and cable stations CN3 and CD7), radio stations (Radio Pública de Ecuador, Radio Carrousel, Radio Super K 800, and Radio Universal), newspapers (El Telégrafo, PP El Verdadero, and El Ciudadano), magazines (La Onda, El Agro, Valles, and Samborondón), and a news agency (Agencia Pública de Noticias del Ecuador y Suramérica). The government considers the former Grupo Isaías outlets to be “confiscated” private media, although they are managed by the state and “are clearly used as a tool for political communication,” said Ricaurte of Fundamedios.

“The state has transformed itself as a communications player,” Ricaurte said, “from being irrelevant when Correa took office in 2007 to now having a leading role.” In building a state media network, the Correa administration has followed the lead of other regional leaders who have invested in government media to further their political agendas. Venezuela’s President Hugo Chávez is the prime example. Since 2002, the Chávez administration has invested hundreds of millions in building a vast media apparatus that has challenged the influence of the private press. In Nicaragua, the government of Daniel Ortega uses official media—including broadcasters, websites, and an email news service—to wage counter-attacks against its critics.

To an even greater extent than his regional counterparts, Correa uses state media to discredit journalists who oppose the administration’s policies. The president often devotes his Saturday radio broadcast to launching verbal assaults against media companies and individual journalists. The outlets most frequently targeted are the national dailies El Universo, La Hora, El Comercio, and Expreso, along with the television network Teleamazonas. Dozens of TV, print, and radio journalists have been targeted in personal and derogatory ways. The president has described critics in the press as “ignorant,” “trash-talking,” “liars,” “unethical,” “mediocre,” “ink-stained hit men,” and “political actors who are trying to oppose the revolutionary government.”

The administration has not confined its message-control efforts to state media. Correa makes frequent use of cadenas, the presidential broadcast addresses, which pre-empt programming on all stations nationwide. From January 2007 to May 2011, Ecuadoran television was pre-empted 1,025 times for cadenas totaling more than 150 hours, according to Fundación Ethos, a nonpartisan Mexico-based research organization. Mauricio Rodas, Ethos’ general director, said that cadenas are traditionally used at times of national emergency, but in the Correa administration, they have become “a tool for propaganda and confrontation.”

In at least 15 other instances since December 2009, the administration has ordered individual broadcasters to give over portions of their news programming to government “rebuttals,” according to Fundamedios. In ordering these rebuttals, the administration claims authority from the country’s broadcast law. Local press advocates say the government is over-reaching, noting that Article 59 of the broadcast law authorizes government use of cadenas “exclusively for information regarding the activities of the respective offices, ministries, or public entities.” In published comments, Communications Secretary Alvarado has justified the use of cadenas on the grounds that they allow the government to convey the “truth” in the face of misinformation.

But time and again, the Correa administration has conflated its own viewpoint with the “truth” and portrayed differing perspectives as “lies.” The arrest of Irma Parra back in April illustrates the president’s intolerance to criticism, said Hinostroza, the Teleamazonas anchor. Parra was arrested in the city of Riobamba after she made a gesture toward Correa’s motorcade that she said was intended to express opposition to the administration-backed ballot questions going before voters in May, news reports said. Correa labeled the gesture obscene, according to those reports, and confronted his constituent and had her arrested.

And when his actions were challenged in the press, the president resorted again to the use of governmental powers to censor and attack. “Correa has an obsession with critical media, and that’s why he wants to regulate content,” said Hinostroza. “The Correa administration has declared the press as its main enemy. … They want to shut us down.”

Carlos Lauría is senior coordinator for CPJ’s Americas program. He led a fact-finding mission to Ecuador in April 2011.

CPJ’s recommendations to Ecuadoran authorities

• Stop the use of outdated criminal defamation laws to silence critical journalists, editors, and media executives.

• Enact legislation to decriminalize defamation laws in line with international standards on freedom of expression.

• Halt the use of retaliatory civil defamation lawsuits that seek disproportionate damages intended to silence critical journalists.

• Ensure that provisions in the pending communication bill in the National Assembly respect guarantees on freedom of expression enshrined in the constitution and in international covenants ratified by Ecuador.

• Use cadenas in compliance with Ecuadoran law, which authorizes their use “exclusively for information regarding the activities of the respective offices, ministries, or public entities.”

• Show greater tolerance toward media criticism and stop personal attacks aimed at discrediting journalists and their news outlets. Halt the use of inflammatory language, such as labeling critics as being “ignorant” or “liars.”

• Put an end to systematic campaigns aimed at discrediting critical journalists, including efforts carried out by media outlets sympathetic to the government.