Posted October 14, 2009

The government’s pre- and post-election crackdown on digital communication illustrates the extent to which it views electronic discourse as a formidable threat to its grip on power. Alongside students, lawyers, and traditional journalists, bloggers have been targeted and arrested in the post-election roundups. At least seven bloggers were among the several dozen journalists rounded up and jailed for their reporting and commentary.

Iran is at the forefront of online repression in the Middle East, combining old-school tactics such as detention and harassment with newer techniques such as online blocking and monitoring. It has also moved assertively to extend—and even expand—longstanding legal restrictions on print and broadcast journalism to online media.

The tactics used by Iranian authorities, while glaring, are being employed to various degrees throughout the region, from Egypt to Saudi Arabia, Tunisia to Syria. A months-long CPJ survey shows that many governments in the region are using both new and time-tested strategies against online journalists, signaling that blogging has become a crucial front in the struggle for press freedom.

• Recommendations

• Audio report

• Français

• العربية

• فارسى

On the CPJ Blog, posts from:

• Tunisia

• Egypt

• Iran

Blogging has flourished in the Middle East, propelled by the region’s unusually high growth rate in Internet use, and the exceedingly restrictive landscape for traditional media. This nexus of demography and repression has led activists, journalists, lawyers, and others online, where they express dissent and report information in previously unimaginable ways. Internet World Statistics, a market research company that compiles online data, reports that the number of Internet users in the region grew 13-fold from 2000 to 2008, far surpassing the two-fold increase worldwide. A June 2009 study by the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, a research institute at Harvard University, estimates that the Arabic-language blogosphere consists of about 35,000 regularly updated blogs. The Farsi blogosphere, according to a separate 2009 Berkman study, comprises a staggering 70,000 active blogs. Iranian blogs are so prevalent that Technorati, the blog search engine and indexing service, ranks Farsi, a language spoken by just 75 million people worldwide, among the Web’s 10 most popular blogging languages.

CPJ defends bloggers who meet fundamental journalistic precepts: Their work is reportorial in nature or offers news-based commentary. Though a large majority of blogs do not meet this journalistic standard, CPJ and other analysts estimate that hundreds, if not thousands, of blogs in the region critically examine issues of public interest. These are issues that traditional media, shackled by government ownership or strict, longstanding prohibitions, often cannot cover.

Take the Egyptian Wael Abbas, who began blogging in February 2005. With a focus on domestic issues, Abbas attracted a loyal but modest readership in his first year of blogging. But when he posted a video of police torture in 2006, he set off an astonishing outcry and altered the nature of blogging in the region. Egyptians had long heard anecdotes of torture in custody, but the video provided evidence. This and other equally damning videos posted by Abbas and others ultimately led to the conviction of several police officers. By November 2008, Abbas said, millions of visitors had come to his blog.

“I cover these topics because I see a lack of reporting” in other media, he said. Abbas, who has received multiple international press and human rights awards, has a high enough profile to deter authorities from taking the harshest retaliatory actions, but he has still been detained, searched, and harassed twice at the Cairo airport. On one occasion, his laptop computer was confiscated. Abbas also told CPJ that he has received repeated threatening phone calls, was pulled off the street and held for hours, and was maligned on television and online as a criminal—which has left him unable to secure regular employment.

Mohamed Khaled, a fellow Egyptian blogger who also posted torture videos, said he felt compelled to risk such harassment. When he first came upon images of torture, he said, “I could not believe my eyes. People had to see this barbarity. … It’s worth the risk.”

Laws and regulatory frameworks

Blogging is policed by overlapping regulations that vary across the region. Iran employs the most elaborate scheme of layered legal restrictions, but virtually all regional countries rely on three basic types of laws to restrict online expression: longstanding press and penal code provisions; emergency laws; and emerging Web-specific laws and decrees.

Penal codes and press laws in the region are typically rife with vaguely defined provisions that criminalize criticism of government and material deemed insulting to religious and public officials. In Syria, blogger Karim al-Arbaji, who was arrested in June 2007, languished in prison until September 2009, when he was finally sentenced to three years in prison by a State Security Court for “spreading false news that weakened the national sentiment,” in accordance with Article 286 of the Syrian penal code. According to the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, al-Arbaji’s alleged confessions were extracted under torture and other forms of duress. The Syrian Center for Media and Free Expression described the case against al-Arbaji as baseless.

In Iran, the press law prohibits the publication of anything that “promotes subjects that might damage the foundation of the Islamic Republic” or “propagates luxury and extravagance.” Amendments in 2000 extended the law to all forms of electronic media.

In a precursor to this year’s massive crackdown, Iranian authorities jailed at least 23 bloggers and online journalists in a four-month period in 2004. Most were charged with security violations, including espionage, while others were accused of morals infractions. Some were tortured and coerced into giving false confessions, according to news reports and CPJ interviews with multiple bloggers. Most were released after posting high bonds, but four bloggers, all of whom had been tortured, remained in custody and were released only after they agreed to write letters attesting to good treatment while held and “confessing” to some or all charges against them.

Syria extends its press law to prohibit electronic publications from publishing political content unless the site is specifically licensed to do so. The publication of “falsehoods” or “fabricated reports” is punishable by fines and prison terms.

Egyptian authorities resort to the country’s 1996 press law, which allows for criminal prosecution of the nebulously defined crime of “spreading false news,” and to the penal code, which bars material deemed insulting. Blogger Karim Amer is serving four years in prison after being convicted in 2007 of insulting Islam and the president under provisions of the penal code. In his postings, Amer had mocked the authority of Egypt’s president and religious institutions. His case was the first time an Egyptian blogger stood trial and was sentenced explicitly for online writings, according to CPJ research.

Egypt and Syria also stifle blogging through the use of emergency laws, which provide few constitutional protections. In Syria, the law grants sweeping powers to monitor and shut down “all forms of expression” and allows authorities to try offenders in military court for ambiguous offenses such as “crimes that constitute an overall hazard.” At least 11 Syrian bloggers have been convicted under the emergency law, and many have served prison time, CPJ research shows.

The excesses of emergency laws are illustrated by the case of Mosad Abu Fagr, an Egyptian blogger, writer, and social activist for the Bedouin community, who writes about social and political problems on Wedna N`ish. Abu Fagr, arrested in 2007 and accused, under an emergency law, of such wide-ranging offenses as inciting riots and driving without a license, was acquitted in February 2008 but not released. So far, at least 13 judicial orders have been issued directing that Abu Fagr be released. Because the Interior Ministry cannot violate the court orders outright, it instead uses the emergency law to circumvent them. Immediately after each order of release—before Abu Fagr has time to leave his prison cell—the ministry issues a new administrative order directing his continued detention. The provisions of the emergency law are such that the government can use this strategy an unlimited number of times.

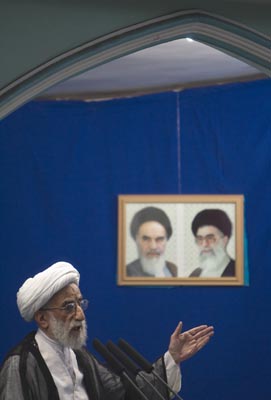

Some countries, led by Iran, have moved toward laws or decrees that explicitly regulate online expression. This year, Iran’s Guardian Council, a powerful 12-member body that is charged with supervising elections and interpreting the constitution among other tasks, approved the Cyber Crime Penal Code, which went into effect in July. By requiring Internet service providers to retain records of all client data for at least three months, the law enables the government to collect information about users and their online practices more efficiently. Anticipating a hefty workload, the judiciary announced that it had created a separate division within the prosecutor’s office to handle offenses under the Cyber Crime Penal Code.

Another disturbing piece of legislation remains in the deliberative phase. The measure would make online expression perceived as “against the will of God” punishable by death. The bill was approved by a parliamentary commission in February and awaits parliamentary and Guardian Council approval. The penalty exceeds parallel provisions in the press law.

Other regional governments are tailoring laws to online journalism. The United Arab Emirates enacted the Cyber Crime Law of 2006, which sets fines of 20,000 dirhams (US$5,400) and prison sentences of up to a year for a number of vaguely defined online acts, such as “abolishing, destroying or revealing secrets or republishing personal or official information,” or insulting religion or family values. Two men who operated an online forum were convicted and fined in 2007 under the law for allowing material deemed defamatory to be posted by a commenter.

Tunisia, Oman, and Jordan have verbal orders or written decrees in place extending civil and criminal liability to Internet service providers, Internet café proprietors, and owners of Web servers, obliging them to monitor and report infractions. Saudi Arabia relies on a 2001 Council of Ministers Resolution, which carries the weight of an executive decree, to regulate Internet use. The resolution prohibits all Internet users from publishing or accessing “anything contrary to the state or its system.”

In Egypt, the Interior Ministry created a Directorate for Computer and Internet Crimes in 2002. Ostensibly designed to combat Internet crimes, it has engaged in “relentless pursuit of bloggers and citizen journalists, invading their privacy, hacking into their personal accounts, and using their blogs against them,” Egyptian blogger Mostafa El Naggar lamented.

Intimidation, arrests, harassment

Bloggers, by their nature, can be more isolated and, thus, more vulnerable to attack than their counterparts in other media. They often work on their own and do not have the organizational resources—including lawyers and money—that can help shield them from harassment. Bloggers are only now forming the sort of professional organizations that journalists in other media have created to try to beat back repressive measures.

Although comprehensive regional data have yet to be collected, research by CPJ and other rights groups has found hundreds of instances in which bloggers have faced harassment, intimidation, and detention in recent years. The tactics of authorities may vary but the goal is often the same: Convince a blogger that the cost of doing battle with the state far outweighs any benefit.

The use of repeated and unsupported police summonses is a favorite tactic; Egyptian police and security agents have developed a particular affinity for the practice. Marwa Mostafa, an attorney for the Legal Aid Unit for Freedom of Expression at the Cairo-based Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, told CPJ that she and her colleagues handled 160 cases of harassment of bloggers in the first six months after the unit’s establishment in 2008.

Authorities have also sought to intimidate bloggers by targeting their families. When Iranian blogger Sina Motalebi fled the country in 2004, authorities arrested his father to compel Motalebi to return or at least to discontinue blogging. (Motalebi stopped blogging for a time but eventually resumed.) In 2001, Tunisian Mokhtar Yahyaoui, a one-time judge who became a blogger after he was dismissed for criticizing the judiciary’s lack of independence, told CPJ that his daughter, a student in Paris, had waited months for a simple passport renewal.

Governments and surrogates have also resorted to smear tactics to discredit bloggers, CPJ research shows. Tunisian authorities have orchestrated especially vitriolic attacks against bloggers; in June, for example, government-backed newspapers and Web sites subjected human rights lawyer and online journalist Mohamed Abbou to scurrilous assaults on his sexual practices. In Egypt, a journalist at a government-owned newspaper agitated against Abdelmonem Mahmoud, a blogger who exposed errors in a military trial, describing him as a national security threat who should be arrested.

Travel bans and other restrictions on movement are old tactics that governments have adapted to rein in troublesome bloggers. Iranian blogger and activist Emadeddin Baghi, who previously served three prison terms, and has been summoned to court dozens of times since 2003, is one of many Iranian bloggers banned from traveling abroad. Abdallah Zouari, a Tunisian reporter who spent 11 years in prison for his newspaper work, endured seven years of government “administrative control” after he was freed in 2002 and began blogging. Under this form of house arrest, the government placed him in a home 300 miles from his family, restricted his movements, limited his ability to work, barred him from Internet cafés, and placed him under constant police surveillance. His ordeal finally ended in August, when he was permitted to reunite with his family. Tunisian journalist and blogger Slim Boukhdhir has been denied a passport since November 2007, while Tunisian lawyer and online writer Mohamed Abbou was prevented from traveling internationally seven times between 2007 and June 2009, when he was finally permitted to leave the country.

When these tactics fail to dissuade critical bloggers from writing, governments have shown their willingness to selectively imprison those who voice critical opinions online.

Imprisoning bloggers serves a dual purpose: Not only is the blogger silenced, but the arrest intimidates others. Iran’s Motalebi, who was once detained, told an audience at a June 2007 Amnesty International lecture that interrogators seemed intent on demonstrating the cost of blogging. He said one interrogator told him: “There are very high costs in blogging, and we want to make you an example of that. Yes, we can’t trace every single blogger who criticizes our government, but we can scare them.”

This posture is common. In 2006, Egyptian Alaa Abd El-Fatah was detained for 45 days without charge after writing in his blog in support of reformist judges and better election monitoring. Abd El-Fatah was among numerous Egyptian bloggers who staked out such positions, but he appeared to be targeted because of his prominence. In Syria, blogger Tariq Biasi was arrested in 2007 for a single comment criticizing security services. A state security court convicted him a year later of “weakening national sentiment” and sentenced him to three years in prison.

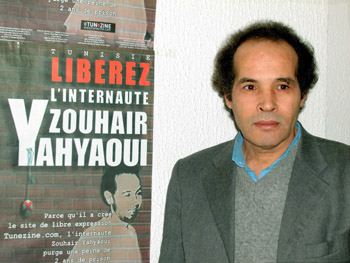

Many regional governments have deplorable records when it comes to the treatment of incarcerated bloggers. A number of prominent bloggers have reported to CPJ, news organizations, and human rights groups that they had been tortured in custody. The pioneering Tunisian blogger Zouhair Yahyaoui, convicted of publishing false information, told CPJ in 2004 that he endured horrific treatment: being hung from the ceiling and being kicked, slapped, and punched. Food was rotten, cells filthy, and health care substandard. Yahyaoui waged several hunger strikes to protest the treatment he endured during 531 days behind bars. Sixteen months after his release, Yahyaoui, 36, died of a heart attack.

Iranian blogger Omidreza Mirsayafi, convicted of insulting government and religious leaders, was just one month into a 30-month prison term when he purportedly committed suicide. Authorities have released no details about the death and refused to allow an autopsy. A photograph published by the Voice of America’s Persian service showed extensive bruising on Mirsayafi’s body.

A technology offensive

Governments engage in four basic strategies: blocking or filtering the content seen by domestic viewers; removing offending material from domestically hosted sites; filtering electronic communications; and monitoring electronic communication. Many countries in the region actively filter Internet content, with Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Tunisia the worst offenders, according to the OpenNet Initiative, an academic partnership that studies Internet censorship. Yemen, Sudan, and Syria engage in extensive but more selective filtering. Morocco and Jordan filter a narrow tranche of content for distinct political reasons. Egypt, Algeria, Lebanon, and Iraq rarely, if ever, filter content, OpenNet Initiative’s research shows.

Internet traffic in Iran, Egypt, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, and the United Arab Emirates passes through servers controlled by the state, facilitating the monitoring or disruption of content. Some countries, such as Egypt, may not filter but they do monitor data. Gamal Eid, executive director of the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information, said the information gathered while monitoring digital traffic is routinely shared with state agencies and used to identify targets for legal action.

Through their elaborate surveillance and filtering regimes, the Iranian and Tunisian governments employ technology to achieve two goals: to monitor, intercept, or alter data, and to block content. In June, The Wall Street Journal reported that Iran had acquired from joint venture Nokia Siemens Networks a surveillance system that enables operators to identify, track, and disrupt data including mobile phone conversations, text messages, e-mails, and any material on the Internet. Lauri Kivinen, head of corporate affairs at Nokia Siemens Networks, said the system was designed to monitor local telephone voice communications only—but added that all systems can be “abused” by operators.

Iran’s filtering regime is so pervasive that it has been described by numerous journalists and communications experts as second only to that of China. As early as 2001, the government ordered Internet service providers to filter content. It created an interagency committee in 2002 tasked with regularly identifying sites to be blocked and keywords to be filtered, according to Iran ’s Telecommunications Regulatory Authority. Iran has also begun developing technology to pinpoint and obstruct undesired Web sites, including blogs.

Tunisian activists, dissidents, and bloggers have long suspected government interference in their digital communications, CPJ research shows. E-mails sent to them from certain sources frequently do not appear in their inboxes at all, or they arrive altered or delayed. In October 2008, unidentified vandals hacked into the independent Tunisian news Web site Kalima, hosted in France, shutting it down and destroying eight years of archives. “The only ones who benefited from this attack were the authorities,” said Lotfi Hidouri, the site’s managing editor. Kalima, which publishes biting government critiques as well as stories about torture and human rights abuses, has seen its staff detained and regularly harassed.

Saudi Arabia, which has one of the world’s most comprehensive filtering regimes, blocks numerous blogs as well as religious, political, and human rights Web sites, and online translation or proxy services. Other regional countries employ commercially available filtering software to identify and block content with varying degrees of effectiveness. Morocco effectively blocks access to sites that criticize the royal family or advocate independence for the Sahrawi of Western Sahara. Yemen’s filtering regime, though technically inferior, is extensive, according to OpenNet Initiative. Bahrain, which has for years filtered political and social content in a haphazard fashion, issued an order to Internet service providers in January 2009 directing them to block sites upon notification from the Culture and Information Ministry. According to the Bahrain Center for Human Rights and CPJ research, more than 1,000 Web sites had been blocked as of September.

Blogging in 2010 and beyond

As Internet connectivity mushrooms in the region, the popularity of blogs has rivaled that of traditional news media. This is especially true with sensitive topics such as sexual harassment, torture, and HIV/AIDS. On topics such as these, bloggers have pushed boundaries and provided cover for traditional journalists to follow.

“Some topics, because of a culturally conservative culture, cannot appear on the pages of a newspaper. If you publish them you will be flooded with complaints from readers, even if no objection from the authorities is forthcoming,” said Khaled El-Sergany, editor of the Egyptian daily Al-Dustur. “But bloggers don’t have to answer to a cultural censor; their readership is more progressive, generally speaking. When they raise certain issues, which then gain traction, it becomes more palatable if we then cover them.”

The blogging phenomenon mirrors in some respects the earlier emergence of satellite television, another medium that reaches across borders and defies easy government repression. As satellite television did to a considerable degree, blogging is undermining the state’s monopoly over mass communication. Governments cannot leverage their printing presses, distribution networks, accreditation requirements, and licenses as effectively as they have for print and terrestrial broadcast journalists. The presence of a deep and growing audience for journalistic blogs, the borderless nature of blogging, the low barriers for a journalist to enter the blogosphere, and the difficulties governments face in controlling the delivery of blogs to readers (even sites that are blocked domestically can be accessed through proxies) are among the chief reasons to be optimistic about the future of blogging in the Middle East and North Africa.

This is not to say that individual bloggers or the practice of journalistic blogging will inevitably prevail over government repression. Individual bloggers face enormous threats; the medium as a whole faces significant challenges. Increasingly, governments are creating new laws to regulate the Internet and amending old ones to encompass online expression. Already authorities are exploiting the isolated nature of bloggers and the lack of institutional protections for online journalists. As the Iranian regime exhibited this year, governments are willing to take severe measures when they perceive a threat to their power.

Yet the excesses of government can backfire, as was the case with the Tunisian blogger Yahyaoui and the Egyptian Abd El-Fatah. Yahyaoui was popular enough before he was sent to jail, but his jailing and premature death turned him into a martyr for Tunisian free expression. Abd El-Fatah, who had been little known outside blogging circles, became a messenger for reform among the public after his six-week detention.

The pace of technical innovation also suggests that every time technology, brute force, or politicized judiciaries give governments an edge, counter-advancements can materialize. A government can invest considerable resources on technical measures to suppress critical blogging, only to have them rendered obsolete by resourceful programmers. Many regional bloggers are at the forefront of innovations to assist online journalists and their readers in circumventing government restrictions. The widely read Egyptian blogger Hossam El-Hamalawy told CPJ that bloggers are “absorbing the culture of Web 2.0 tools. They will leverage our work in ways we thought unimaginable before.” A group of Egyptian bloggers who are also computer programmers, chief among them Amr Gharbeia, have been promoting technical know-how through blogs and workshops. A Tunisian blogger who writes under the name of Astrubal has developed a tool to help people “living under repressive regimes” find out what Web pages are blocked in their country. (His own blog is blocked in his native country.)

But technical measures must be accompanied by professional solidarity. To combat government repression, bloggers and their advocates must object in chorus against excessive laws, speak forcefully on behalf of colleagues who are harassed and jailed, educate their readers and enlist their support. Bloggers are starting to take these steps now. An increasing number of bloggers’ associations seek to speak in a unified voice; national and regional groups are devoted to advocating on their behalf; and multiple homegrown initiatives advocate for a free and uncensored Internet. The goal is the same as it has been for earlier generations working for newspapers and broadcasters: Set a steep political price for any government that resorts to harsh, repressive measures.

To regional governments:

- Amend legal provisions, whether in the penal code, press law, or elsewhere, that criminalize freedom of expression online, bringing them in line with international legal standards. Release all individuals serving prison time for the expression of critical opinions online.

- When promulgating Web-specific laws, ensure that they comply with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- End the monitoring of private electronic communications, unless accompanied by a court order based on a proven national security or law enforcement need. Such monitoring must be construed narrowly and granted only to meet a specific, compelling, and close-ended necessity.

- Eliminate legal obligations compelling service providers and other third parties to monitor client use and report such information to authorities.

To technology firms:

- Companies that sell technology that can be used to identify and target bloggers must ensure their product is not used by governments to restrict online freedom of expression. Companies should conduct a Human Rights Impact Assessment prior to such sales, as established by a set of principles formulated by the Global Network Initiative, which seeks to ensure that technology companies uphold international freedom of expression standards.

To the U.S. government:

- In all dealings with countries that harass or prosecute bloggers, representatives of the U.S. government should publicly speak out in favor of individuals whose right to online expression is habitually violated.

- Revise the State Department’s annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, amending Section 2 (Respect for Civil Liberties) to include a subsection on violations of online free expression.

To member states of the European Union:

- Make use of existing bi- and multilateral trade instruments, in particular the human rights clause included in cooperation agreements between the EU and third countries, with the goal of reducing violations of the right to online expression.

- Based on analyses provided by in-country European Commission Delegations, expand the practice of issuing advisories to local technology firms, urging restraint when selling technologies that can be used to curb online dissent.

- In all dealings with countries that harass or prosecute bloggers, representatives of the European Union and its constituent member states should publicly speak out in favor of individuals whose right to online expression is habitually violated.

- Consistent with the mandate of the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights, the European Commission should provide support to local groups defending freedom of expression and in particular the right to online expression.

- The Human Rights Subcommittee of the European Parliament should hold a hearing focusing on online freedom of expression and invite testimony from bloggers, particularly those from the Middle East and North Africa. The European Parliament should work on a resolution defending the right to freedom of expression, particularly online expression the Middle East and North Africa.