Drug fueled violence against the press has spread to the central state of Michoacán. At least two journalists’ lives have been lost, and self-censorship is taking root.

APATZINGÁN, Mexico

Knives were no longer pressed against his abdomen. The gun barrel had moved away from his head. But Antonio Ramos remained motionless under the dark sky, a sweater still pulled over his head. “I don’t remember how long I stayed knelt on the ground,” he says. “I heard the truck drive off, but I wasn’t sure if I was alone or if somebody was still there ready to shoot me.” Eventually, Ramos stood up, and found himself in a field with the lights of Apatzingán twinkling a few miles off.

![]() Hear Antonio Ramos tell his story (in Spanish)

Hear Antonio Ramos tell his story (in Spanish)

The kidnapping had occurred earlier that evening, on May 22, 2006. Ramos, a longtime journalist in Apatzingán, a small city in the central Mexican state of Michoacán, had signed off on his daily television newscast. Like other reports of that time, his broadcast detailed the wave of violence sweeping Mexico, and especially Michoacán, as drug cartels fought for turf. Ramos left the building and was approaching his car when gunmen grabbed him and put him in a pickup truck. They knew all about Ramos and his family and said “there’d be hell to pay” if he kept up his reporting. Days earlier, Ramos had received a similar message at the station from an anonymous caller. It was no doubt upsetting, but Ramos had continued with his work. Since the kidnapping, however, Ramos fears for his safety and the future of journalism in Mexico. “I still hold that romantic vision of a reporter trying to uncover injustices,” says Ramos. “But I question how we can continue that work under threat.”

His fears appear to be well-founded. In Mexico, already one the most dangerous countries for journalists in the world, Michoacán now ranks alongside northern states such as Baja California, Chihuahua, and Tamaulipas, where journalists have died or suffered beatings for covering the drug trade and the powerful Gulf and Sinaloa cartels. Anxious to protect their profits and plaza, as drug territory is known, traffickers are willing to make an example of probing reporters by means of murder, beatings, and threats.

The spreading danger owes to a bloody battle between the two cartels that has moved south, to the central Mexican states of Michoacán and Guerrero, along with the southern states of Veracruz, Tabasco, and Quintana Roo. With key shipment routes to the United States at stake, the all-out war between well-financed criminal groups has raised violence to unprecedented levels in parts of Mexico in the past three years. Such violence left more than 2,000 people dead in Mexico last year. In the first half of 2007, the drug wars claimed an estimated 1,400 people, according to Reforma, a leading daily in Mexico City. The situation has analysts comparing Mexico’s challenge to that faced by Colombia in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when narcoterrorism threatened the stability of the government.

Violence has grown more brutal, with executions conducted in broad daylight and beheadings becoming more common. On October 25, 2006, several armed men in military gear burst into the Sol y Sombra nightclub in Uruapan, a city in eastern Michoacán known for avocado crops. As the crowd looked on, the men dumped five human heads onto the dance floor. Police interpreted the gruesome act as a message from the Gulf cartel to the Sinaloa group. Similar violence has been reported in the city of Apatzingán, a few hours’ drive southwest of Uruapan. Indeed, crime has changed Apatzingán’s image to the degree that it is known as much for drug-related violence as for being the place where Mexico’s revolutionary leaders gathered nearly 200 years ago to draft the country’s first constitution.

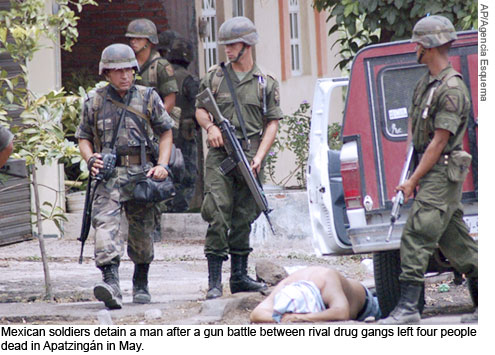

In early December 2006, after barely one week in office, President Felipe Calderón deployed thousands of soldiers to Michoacán and other states plagued with drug violence. Today, soldiers regularly assume crime-fighting roles in Mexico’s small towns and cities, searching houses, patrolling streets, and overseeing checkpoints. In the countryside, they eradicate marijuana and heroin poppy crops. It has not been easy. On May 7, five months into the government’s crackdown on the cartels, a deadly clash between soldiers and suspected drug gang members involving AK-47s and grenades erupted outside an elementary school in Apatzingán. The long-term effectiveness of the campaign remains in question, although there has been a lull in the violence since June. Most security analysts attribute the calm to a drug cartel cease-fire, reportedly struck between leaders of the Gulf and Sinaloa cartels. It is a truce that could end at any time.

For reporters in Michoacán, and in other parts of rural Mexico where cartels hold sway, the mood remains tense. This year, at least 20 journalists in the state have been levantados, or “picked up,” by armed men allegedly belonging to rogue police groups or organized gangs, according to Apro, a news service run by the Mexico City-based Proceso newsweekly. Journalists are routinely threatened and sometimes beaten. They face the very real possibility of being killed or “disappeared.” Crime reporters are common targets, but so are editors and general-assignment reporters. “The risks affect all of us,” says Amada Prado, 37, a longtime newspaper reporter for La Opinión in Apatzingán. Earlier this year, the newspaper installed a video monitoring system at its offices. According to Prado, “Your association with the newspaper can be reason enough for criminals to target you.”

Yet direct attacks against journalists, particularly those working for small news organizations, are barely noticed in Michoacán. A case in point is the light coverage given to the death of Jaime Arturo Olvera Bravo, who was shot at close range on March 9, 2006, while waiting with his 5-year-old son at a bus stop in the Michoacán town of La Piedad. The 39-year-old freelance journalist, a former correspondent for La Voz de Michoacán, a popular daily, had reported regularly on local police corruption. The state prosecutor told local reporters that the murder investigation found no link between Olvera’s work and his death. Aside from initial press reports, Olvera’s death has received little follow-up in the press. In large part, such news falls under the radar of the national press. Locally, Olvera’s colleagues worry that aggressive reporting about such crimes will result in similar attacks. Talk of police investigations is met with apathy. “None of these crimes are solved,” says a veteran reporter in Michoacán who knew Olvera and spoke on condition of anonymity, as he himself has received several threats for his crime reporting. “How can there be real investigations if so many special interests exist between the cops and criminals? You get the strong sense that those in power would prefer to see reporters who do their job well just disappear.”

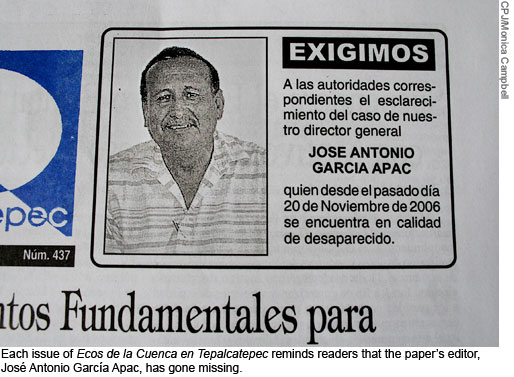

There is also little follow-up on the case of José Antonio García Apac, editor of Ecos de la Cuenca en Tepalcatepec, a local newspaper. On the evening of November 20, 2006, García pulled over on his way home to Morelia, the state capital, to call his family. While on the phone with his son, García was overheard responding to several men who asked his identity. They then ordered him to hang up. Sounds of García being dragged away were heard before the line went dead. The 55-year-old father of six has not been seen since.García’s wife, Rosa Isela Caballero, has demanded a thorough investigation of her husband’s disappearance, but the authorities say they have no leads to follow. Pessimistic and with little confidence that her husband’s case will be solved, Caballero plans to have her husband declared legally dead.

García, nicknamed “El Chino,” reported regularly on organized crime in Michoacán. Caballero recalls that in February 2006, García compiled a list of Michoacán state officials, including police officers, who he believed were linked to criminal groups. He took the list to his sources in Mexico City’s federal anti-organized crime squad for corroboration, a move that some believe may have backfired and played a role in García’s disappearance. “I told him to stop investigating, that he was putting his life in danger,” Caballero says. “But journalism was his passion.”

Despite García’s absence, Ecos de la Cuenca en Tepalcatepec still circulates, although on a bimonthly instead of weekly basis. “It hasn’t skipped a beat,” says Caballero, 49, who now oversees the newspaper. Featured on the upper right-hand side of each issue: a passport-size photo of García, with a caption demanding that his case be solved. Caballero says her children worry that her increasingly activist profile is putting her life at risk. “I realize that,” she says. “But my husband started the paper and kept it going for so many years. He would want it to continue.”

In the meantime, news of threats against the regional press corps swirls throughout Michoacán. “It’s our colleagues reporting in the most remote areas of the state who we worry about most,” says Sergio Cortés Eslava, a 43-year-old reporter for Quadratín, a local news agency based in Morelia. He should know. On the afternoon of November 14, 2006, armed men forced Cortés and photojournalist Alberto Torres out of their car as they left the remote mountain town of Aguililla, in an area known as tierra caliente, or “hot country.” The journalists had just finished covering the death of six police officers in an apparent ambush nearby. Cortés and Torres were put in a black dual-cab truck with tinted windows and driven down a dirt road. They were interrogated about their work for about an hour and then released. “They told us they’d let us go for now,” says Cortés, “but to be careful about what we write about. They said the area wasn’t safe.” He reported the incident to the state’s human rights representative. Police protection was offered, but Cortés refused. “Mistrust of police runs deep,” he says

Some reporters have written editorials about the increasingly dangerous environment to raise awareness about the lack of press freedom in Mexico. The day after his abduction in May of last year, Antonio Ramos sent a letter to the governor of Michoacán and then-President Vicente Fox alerting them to threats against journalists and the determination of organized gangs and drug traffickers to silence them “at any cost.” But a groundswell of political support for the press has yet to appear.

|

Mexico by the Numbers Nationwide statistics: 6 journalists have been slain in direct relation to their work since 2000. 11 other journalists have been murdered in unclear circumstances since 2000. 5 journalists have been reported missing since 2005. 8 percent of journalist murders have ended in convictions. For a complete database of journalist deaths in Mexico, visit www.cpj.org/deadly. |

In February 2006, at CPJ’s urging, the Fox government appointed a special prosecutor to pursue crimes against the press. But the office lacks jurisdiction to investigate aggressively, and can intervene in homicide cases only at the request of state authorities. Crimes related to drug gangs are also off-limits, as they fall under the jurisdiction of the attorney general’s anti-organized crime division. President Calderón calls the dangers facing journalists “unacceptable,” but no changes have been made to the current legislation granting the special prosecutor’s office more investigative power.

At the local level, some politicians prefer to downplay the dangers journalists face. “I’m not sure what journalists are complaining about,” says Genaro Guízar Valencia, a congressman who is running for mayor of Apatzingán this year. “I can travel throughout the state without a problem. But then again, I might not be a threat to certain groups. If you pose a threat, things get complicated.”

Journalists who walk an independent line also have little political pull. Raymundo Reyes, publisher of Z de Zamora, a small alternative daily published in northern Michoacán, has taken several financial hits to maintain his paper’s independent stance. Next to the masthead, a note to readers states that the paper prohibits its reporters from accepting any form of payment that could compromise their work. Paid editorials and political advertisements are indicated as such–policies not always followed by small Mexican papers, which largely survive on the basis of political ads. The state government still advertises with the paper, but the municipal government stopped running ads a while ago. “We’ll get pressure from local politicians to change our policies, but I won’t budge,” says Reyes. As a result, the paper finds itself sidelined. Reporters struggle to land interviews with officials or receive notice of municipal meetings. “We’re marginalized,” says Reyes. “Do you think the officials here will come to our side if something happened to one of our reporters? No way.”

Rafael Gomar, a political reporter for Z de Zamora for 16 years, agrees. “If you stick to your ethics and refuse the chayote, you barely eke out a living off journalism in rural Mexico,” says Gomar, who runs a laundermat to supplement the 1,300 pesos (US$120) he makes a week at the paper. Chayote is slang for the payola that journalists receive from politicians, police, and organized criminals in order to serve as a voice box or silencer of certain news. “Most times,” says Gomar, “you are paid not to report.”

Reporters in Michoacán maintain that chayote divides the press. “Before, we had journalists’ groups and associations in Michoacán,” says a journalist based in Morelia who spoke on condition of anonymity to avoid creating tension among his fellow reporters. “But they started breaking up when different groups started buying off some reporters. You knew who they were when you saw them walking around with hundred-dollar bills in their wallets and driving new cars.”

Police also make for uncertain allies. One of Mexico’s open secrets is that organized criminals collude with the cops. In many cases, alliances between the two groups involve poorly paid police officers (whose average monthly salary is 4,200 pesos, or US$375) taking bribes in exchange for alerting the cartels to roadblocks, or to facilitate smuggling. “Corruption happens when you’re dealing with some of the world’s wealthiest criminal groups,” says a top crime investigator for the state of Michoacán who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of security concerns. “No government operation will be able to beat back that reality.”

Unable to rely on the government or trust the police, journalists in Michoacán now practice what many of their colleagues along the northern border have practiced for years: self-censorship. “The days of investigating crimes, figuring out who did what and why, are over,” says Ramos. The basic rule is simple: Do not upset the bad guys. That means omitting full names and nicknames. Execution-style killings, common throughout Mexico, cannot be linked to a particular organized gang. And publishing photos of a crime scene is avoided. “If we do report on crime–and we often just skip running certain crime stories altogether these days–we just include the most basic details: the name of the victim, where he was found, and when,” says Reyes.

Indeed, it is not a question of whether a reporter has the courage to report aggressively. “Self-censorship is now considered a legitimate form of protection,” says Leonarda Reyes of Mexico’s Centro de Periodismo y Ética Pública (Center for Journalism and Public Ethics), which promotes independent journalism, transparency, and initiatives to combat corruption. And she does not see the picture changing anytime soon. “As long as the demand for drugs remains strong in the United States, these criminal groups will remain in power,” says Reyes (no relation to the journalist). Indeed, Mexican cartels are considered the world’s leading distributors of cocaine, according to the 2007 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, published in March by the U.S. State Department. Mexico is also the largest foreign supplier of marijuana to the United States, as well as a major supplier of methamphetamine.

Not long ago, journalists like Ramos and Cortés didn’t worry so much. To the contrary, crime reporters living in Michoacán had the advantage in covering their state. They knew the politicians, police, and criminals. They held breakfast meetings in the same cafés, swigged tequila in the same cantinas, and played soccer with cops. Getting close to drug traffickers was possible if one headed to the horse races, which cartels sometimes organize.

But those days are over. The toxic environment has convinced some reporters to move on. Journalists in Michoacán estimate that about one-quarter of their colleagues have left the profession in the past three years. And as in other parts of Mexico, some reporters have either moved to another state or left the country altogether. Journalists who remain in Michoacán see no reason to take risks. “We’re rooted here,” says Prado, the reporter in Apatzingán. “We don’t parachute in, report, and leave. We live here with our families, and the only way to keep on with a normal life is to protect ourselves by not writing about certain things. Those who chose to pursue the story are filling the cemetery.”

Monica Campbell is a freelance journalist and CPJ consultant based in Mexico City. She conducted this research mission in August. Her last piece for Dangerous Assignments explored the unsolved 2006 killing in Mexico of U.S. documentary filmmaker Brad Will.