Class and ethnic tensions stir antagonism between the Morales administration and the press. As a new constitution is being written, fears emerge that the media could face new restrictions.

|

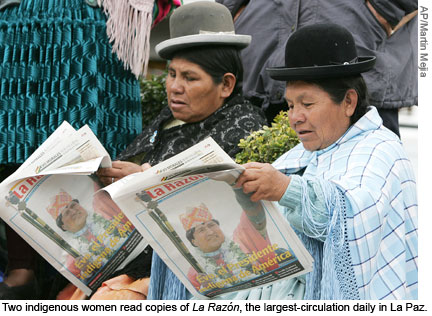

LA PAZ, Bolivia Journalists swarmed the presidential palace on a warm spring day as Evo Morales called a press conference to slam two media reports. Clutching a copy of La Razón, the largest-circulation daily in this capital city, the Bolivian president declared that the paper “lies and misinforms constantly.” And he warned the Spanish owners, “I’m thinking of nationalizing it.”

Morales blasted the reports as part of a campaign to damage the reputation of his government. “Bolivians will judge these kinds of distortions that come from some media outlets,” he said. La Razón fired back with an editorial that said Morales’ reaction was so excessive, it had no precedent in the 25 years since democracy was restored to this Andean nation of 9 million. Such confrontations come regularly these days in Bolivia, where the second-year socialist president has made a practice of trying to discredit the media. The rifts could be written off as the usual tension between the press and politicians, but they come at a historic moment for Bolivia, which is drafting a new constitution that would give greater power to the country’s marginalized indigenous majority while addressing contentious issues such as land reform, regional autonomy, and fundamental human rights–including press freedom.

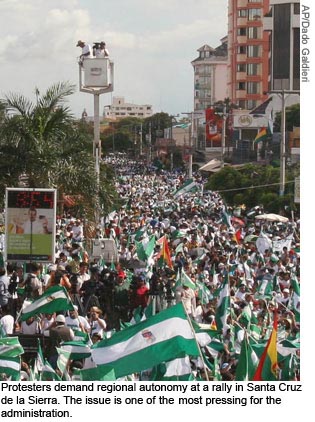

The conflict reflects growing ethnic and class tensions in Bolivian society. Based in the country’s western highlands, the predominantly Quechua- and Aymara-speaking indigenous population is largely impoverished and rural, but with Morales’ election in 2005 they have become politically ascendant. Economic power is concentrated in the lowland city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, which is dominated by a European-descended, Spanish-speaking elite. With a conservative, pro-business outlook, they control much of the national media. Morales’ constant critiques, and much of the media’s own coverage, play on this ethnic and economic divide.

Since he took office in January 2006, Morales and his administration have accused private media of being aligned with antigovernment forces. The president, an Aymara Indian and former coca farmer, has said that “the number one enemies of Evo Morales are the majority of the media.” In September 2006, his government issued a list of what the president called Bolivia’s most hostile journalists. The list, published by the pro-government biweekly Juguete Rabioso and the official news agency Agencia Boliviana de Información (ABI), identified top executives and journalists with major media outlets such as La Razón and El Mundo; the PAT, Red Uno, and Unitel television networks; and Radio Fides and Radio Oriental. CPJ’s Recommendations

CPJ calls on the Bolivian government to implement the following recommendations.

“The capitalist system is using the media against the government,” Morales told a CPJ delegation in a meeting in June. “Journalists sympathize with me, but the media owners are aligned in a campaign against my government.” The press, he said, “is discriminating against the indigenous people.” Several Bolivian journalists and press organization leaders have warned of the consequences of such public antagonism. In particular, they said, journalists covering street protests and other public gatherings have found themselves vulnerable to harassment and attack by pro-government forces. “President Morales has identified certain media outlets as enemies of his government, and this attitude has led to physical attacks and harassment against journalists,” said Renán Estenssoro, president of La Paz’s oldest press group, the Asociación de Periodistas de La Paz. “Groups controlled by the government have harassed reporters for their criticism.” The association has documented 13 attacks against the press since Morales took office, a rate that spiked with the president’s aggressive rhetoric. In January, 11 journalists, photographers, and camera operators were assaulted by pro-Morales demonstrators in the central city of Cochabamba. Thousands of demonstrators–including indigenous groups and members of the ruling leftist party Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS)–had taken to the streets to seek the ouster of provincial Gov. Manfred Reyes Villa after he announced that he would seek a referendum granting greater autonomy to Cochabamba province. Protesters accused the journalists of being biased against Morales. And in Patacamaya, on March 21, La Razón reporter Wilma Pérez and photographer David Guzmán were briefly taken hostage by a group of farmers opposing a construction project by the ELFA electric company. In this instance, the journalists were accused of being “liars.” The two were able to escape unharmed the next day. “Bolivians,” Morales told CPJ, “are reacting to lies and accusations against my government.” The president argued that journalists working for state-owned media have also been subject to assault and harassment. In December 2006, for example, unidentified assailants tried to toss homemade bombs into the offices of state-owned Canal 7 in Santa Cruz. With an annual average income of 8,000 bolivianos (US$1,010) in 2005, according to World Bank data, Bolivia is the poorest country in South America. It is also a country that has undergone profound political and cultural change during Morales’ brief tenure as the nation’s first indigenous president. Leader of the MAS party, he won the December 2005 elections with more than 50 percent of the vote, the highest percentage in the country’s modern history. “My government represents a new idea of peace and social justice,” Morales told CPJ. “We stand for the popular movements that have been vilified for a long time. We don’t want any more exclusion; we want the popular movements to participate in Bolivia’s decision-making process.” During his first year in office, Morales undertook an ambitious array of initiatives, including the controversial nationalization of natural gas and oil fields, the election of a constituent assembly to rewrite the country’s constitution, and land reform. One of the hottest issues is his support for the production of coca leaf, Bolivia’s main crop and one that the United States has sought to eradicate. About 55 percent of the Bolivian population is indigenous, according to the U.S. State Department. Another 30 percent is mestizo–of mixed indigenous and European ancestry–and 15 percent have white European ancestry. The indigenous population relies predominantly on farming as a means of survival–but it is a bare one, and it contributes only a tiny fraction to the national economic output. Business leaders centered in Santa Cruz, well aware that they drive Bolivia’s economic engine, have sought greater political autonomy, with some pressing a muscular separatist agenda. As far-reaching as Morales’ domestic initiatives may be, analysts say that addressing this push for autonomy may be the president’s greatest challenge. And for the press, this volatile mix of ethnicity, class, and political power has potentially vast implications. Bolivia Snapshot Radio: About 800 stations, three-quarters of which are FM. La Paz and Santa Cruz de la Sierra have the largest concentrations. Television: About 190 channels across the country. National networks are based primarily in Santa Cruz. Newspapers: About 50 are in circulation. Half are based in the capital, La Paz, and eight are based in Santa Cruz. Most have limited circulation. Source: Edgar Ramos Andrade/National Directory of Media by Municipality The current constitution, first drafted in 1967, and the country’s 1925 Printing Law now provide the basic legal framework for press freedom. Article 7 of the Bolivian constitution states that “everyone has the right to freely express his or her ideas and opinions through the media,” while the Printing Law shields the media from censorship and allows for confidential sources. In interviews with CPJ, journalists and advocates said that the Printing Law is a sound piece of legislation but should be updated; the constitution, they said, should be strengthened. For now, though, journalists and press groups are more concerned about losing ground. MAS delegates and other government supporters have rolled out a series of proposals that would restrict the media. They have publicly called for the creation of a “news ombudsman” to protect citizens from perceived defamation and to guarantee a right to respond. The pro-government press workers’ union, the Federación de Trabajadores de la Prensa de Bolivia, has introduced one proposal banning media owners from having interests in other businesses, and another giving the government greater latitude to pull broadcast concessions, according to the group’s executive secretary, Marcelo Arce Rivero. And in May, an assembly committee drafted a controversial article asserting that the right to express ideas and opinions through the media should be conditioned on their being “truthful, timely, and transparent.” The measure, which has run into resistance in the full assembly, appears to contradict Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights–ratified by Bolivia in 1982–which guarantees “the right to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds.” José Antonio Aruquipa, delegate for the conservative opposition party Podemos, said that Morales and his allies are intent on using the constitutional process to curb free expression. “The administration and the MAS party are following on Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro’s path and intend to replace Bolivian democracy with a totalitarian regime,” he said. Not so, say top officials. Vice President Álvaro García Linera told CPJ that the government has no plans “to impose coercive mechanisms” on the press. “We respect and seek to promote freedom of expression.” Until recently, the state media had been composed of three main outlets: television station Canal 7, the news agency ABI, and Radio Patria Nueva. But the La Paz government–taking a cue from Venezuela, which has begun an ambitious state media-building effort–has also moved to create more state broadcasters. A newly launched network of community radio stations, called Radios de los Pueblos Originarios de Bolivia (Radios of the Native People of Bolivia), is being financed with a 15 million bolivianos (US$2 million) investment from the Venezuelan government. More than two dozen of these stations are already broadcasting to rural and indigenous communities. In a country where roughly three-fifths of the population is illiterate, according to the World Bank, radio is a vital medium. “These community stations are allowing many Bolivians who live in remote rural areas to have a voice,” Morales told CPJ. “Our goal is to educate and inform people who don’t have access.” The Morales administration has said much the same about the handful of privately owned television networks that dominate the market. Principals in the Santa Cruz-based networks Unitel and Red Uno, for example, have been prominently involved in opposition political parties–an arrangement the government calls “promiscuous.” Local journalists and editors acknowledged that some news coverage has been politicized. “We are losing our capacity to be impartial and this is violating citizens’ right to be informed,” said Raúl Peñaranda, a prominent journalist and former director for the weekly La Epoca. A May study done by Unir, a democracy-building foundation, found that television networks provided little balance in their coverage. In particular, the study cited Unitel. The network disputed the notion that Unitel is biased against the Morales administration, saying that its journalists are fulfilling their traditional duties as critical watchdogs. “We have treated previous presidents the same way–there is no difference at all,” said News Director José Pomacusi. “Our work may not be impeccable or perfect, but it is just as imperfect as it was in prior administrations.” For some in the government and the press, there may be benefits in confrontation. Morales has acknowledged that “attacks from the right help me; they make me stronger.” Said Unitel’s Pomacusi: “Our audience is growing more and more since Evo Morales engaged in this campaign against us.” Yet the barrage of criticism is creating problems for the Bolivian press. “The administration believes that any criticism is part of a conspiracy,” said Pedro Rivero Jordán, executive director of the Santa Cruz daily El Deber and president of the national press association. “There is freedom of expression in Bolivia, but the president’s constant verbal attacks are sending some worrying signals.” Journalists and press organizations have started debating whether self-monitoring could neutralize the rhetorical excesses of both government and media. In May 2006, some press groups, unions, and media owners created the Consejo Nacional de Ética (National Ethics Council), an initiative intended to publicize improper press actions as a way to curb such behavior. But without widespread professional support, the council has proved unproductive thus far. As the deadline for the new constitution approaches, journalists continue to express alarm that the government’s relentless finger-pointing could expose them to greater physical threats. But the larger concern for members of the media is the constituent assembly and its plans in regard to press freedom. “There is an atmosphere of increasing tension,” said Rivero, “and there is a lot of uncertainty.” Carlos Lauría is CPJ’s senior program coordinator for the Americas. |

The threat, however hyperbolic, reflects the increasingly antagonistic relationship between Morales and the Bolivian press. La Razón, owned by the Madrid-based Prisa Group, had published cover stories on two consecutive days that had angered Morales–one claiming that state revenue had dropped after the oil industry was nationalized, the second asserting that Bolivia had lost $600 million in U.S. aid that was predicated on market reform.

The threat, however hyperbolic, reflects the increasingly antagonistic relationship between Morales and the Bolivian press. La Razón, owned by the Madrid-based Prisa Group, had published cover stories on two consecutive days that had angered Morales–one claiming that state revenue had dropped after the oil industry was nationalized, the second asserting that Bolivia had lost $600 million in U.S. aid that was predicated on market reform. Though top government officials have asserted that they want to promote free expression, Bolivian journalists and free-press advocates are concerned about several constitutional proposals that would restrict the work of the press. One measure appears to peg “free” expression to what the government would consider truthful; another would establish an official ombudsman to act against perceived defamation.

Though top government officials have asserted that they want to promote free expression, Bolivian journalists and free-press advocates are concerned about several constitutional proposals that would restrict the work of the press. One measure appears to peg “free” expression to what the government would consider truthful; another would establish an official ombudsman to act against perceived defamation. The president’s aggressive media tactics also illustrate a growing trend toward confrontation among Latin American leaders. The starkest example is Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez Frías, who has made media bashing a part of his daily arsenal and has moved to restrict the flow of information. Like Chávez, Morales and his administration argue that many Bolivian media outlets skew coverage in favor of business and other special interests. The Bolivian media have made themselves vulnerable to such charges, many journalists acknowledge, by allowing lapses in ethics and standards.

The president’s aggressive media tactics also illustrate a growing trend toward confrontation among Latin American leaders. The starkest example is Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez Frías, who has made media bashing a part of his daily arsenal and has moved to restrict the flow of information. Like Chávez, Morales and his administration argue that many Bolivian media outlets skew coverage in favor of business and other special interests. The Bolivian media have made themselves vulnerable to such charges, many journalists acknowledge, by allowing lapses in ethics and standards.

If all that weren’t enough, in a May meeting in Cochabamba, Bolivian government officials appeared to take press freedom advice from Cuban Minister of Culture Abel Prieto, who urged them to create a press tribunal to punish offending media owners. That suggestion, while warmly received by officials, has yet to be made into a formal proposal.

If all that weren’t enough, in a May meeting in Cochabamba, Bolivian government officials appeared to take press freedom advice from Cuban Minister of Culture Abel Prieto, who urged them to create a press tribunal to punish offending media owners. That suggestion, while warmly received by officials, has yet to be made into a formal proposal. The project has generated a debate on whether the government will use these stations as instruments of propaganda. Gastón Núñez, the official who runs the project, said the network does not carry government propaganda and is looking for ways of financing the stations that would not rely on state funds. Local journalists scoff. “These stations are clearly not independent and balanced in their coverage,” said Andrés Gómez, news director for the Catholic Church-funded radio network Erbol.

The project has generated a debate on whether the government will use these stations as instruments of propaganda. Gastón Núñez, the official who runs the project, said the network does not carry government propaganda and is looking for ways of financing the stations that would not rely on state funds. Local journalists scoff. “These stations are clearly not independent and balanced in their coverage,” said Andrés Gómez, news director for the Catholic Church-funded radio network Erbol.