Brad Will was shot down while documenting civil unrest in Oaxaca. No one has been charged. Is the government covering up?

| OAXACA, Mexico |

Posted April 17, 2007

|

|||

| It was a scene played out numerous times during the months-long conflict that embroiled this southern city, the state capital of Oaxaca. Antigovernment protesters, manning street barricades and armed with clubs, bottle rockets, and pistols, clashed with heavily armed plainclothes men working for the embattled state governor.

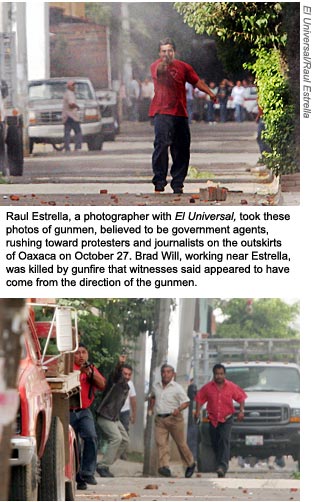

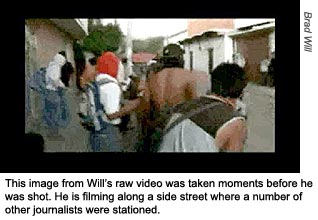

Moving swiftly, the armed men fired at the protesters. Will crouched near the side of the street, letting his camera roll. The chaotic scene shows protesters jockeying for position and hurling rocks, with a series of gunshots and exchanges overheard, including somebody shouting, “Stop taking photos!” Then a gunshot is heard whizzing toward Will; the bullet hits him in the center of his upper abdomen. He screams, falls, and utters “Help me” in Spanish. More gunshots follow. A second bullet soon hit Will’s right side, gliding underneath the skin and eventually lodging itself in his left hip, according to Luís Mendoza Canseco, who, as Oaxaca’s chief medical examiner, performed Will’s autopsy. Neither bullet left Will’s body. The armed men shooting at the protesters were photographed, and the 9 mm bullets found in Will’s body matched the type of weapon carried by at least one of them, according to the Will family. Yet the investigation has gone nowhere. Days after Will’s death, two men accused in the shooting–local town councilor Abel Santiago Zárate and his security chief, Orlando Manuel Aguilar–were detained. But they were released on December 1 after state Judge Victoriano Barroso Rojas ruled that they had used .38-caliber pistols and were not close enough to have shot Will. The men said they had only fired into the air. His family’s grief mingled with rage as they saw authorities in Oaxaca start a campaign that would allow the guilty to go free and “twist everything around,” said Will’s mother, Kathy, in an interview in Mexico City. Sitting beside her, Will’s father, Howard, said: “There are lots of witnesses, lots of photographs. And you’ve got prime suspects … at least five individuals photographed with weapons who have been identified. It’s just preposterous.” That astonishment grew on November 15, when Oaxaca State Attorney General Lizbeth Caña suggested that the second shot may have been fired point-blank by a protester transporting Will to the Red Cross. “That was clearly impossible,” Canseco said in an interview in his office, shaking his head. The investigation in the Will case was “sloppy from the start,” he added, with state prosecutors drawing unsupported conclusions from his autopsy. Further, Canseco said, the second bullet was fired at no less than 13 feet (4 meters), and struck Will almost immediately after the first. “There is no doubt in my mind that both shots occurred before Will was picked up and put in a vehicle,” he said. Amid mounting criticism, Caña later distanced herself from theories that blamed Will’s death on the protesters. At least eight journalists were in the same area as Will that day, including a reporter, six photographers, and a television camera operator. Journalists interviewed by CPJ described a hectic scene: As the armed agents charged at protesters, Will maintained a more exposed position even as his colleagues pulled back. “Brad wasn’t trying to be a hero,” said Diego Osorno, a reporter for the Mexican newspaper Milenio. He was a few feet from Will during the confrontation, attending to Milenio photographer Oswaldo Ramírez, who was shot below the knee. “Brad was in a dangerous position like the rest of the photographers and reporters there,” Osorno said. “What is clear is that officials dressed as civilians, armed with pistols and rifles, were photographed firing into a crowd. Somebody is dead, others are injured, and the guys who did it are still working.” Raúl Estrella, a veteran El Universal newspaper photographer who was on the scene, said he barely escaped death during the confrontation. “Zoom! Zoom! A bullet whizzed by each ear,” Estrella said. The conflict in the colonial city of Oaxaca started May 22, when a routine teachers’ strike over more pay and better working conditions snowballed into a catchall antigovernment protest movement. The simmering unrest boiled over when Oaxaca Gov. Ulises Ruiz Ortiz, a member of Mexico’s old-guard Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), ordered police to break up protest camps in the city’s main plaza on June 14. The dislodging of protesters turned violent and strengthened the protest movement, which was eventually led by a leftist umbrella group called the Popular Assembly of the People of Oaxaca (APPO). The protesters left their own trail of aggression, essentially taking over the capital, clashing with pro-government groups, and seizing a dozen private radio stations. Journalists covering the conflict were beaten by both the protesters and gangs of police dressed in civilian clothes. In all, some 20 people died during the unrest, most of them protesters. No one has been indicted in any of the deaths. Will’s killing drew worldwide attention and transformed the conflict overnight into a bigger international story. His death also sent a shock through independent media circles in New York. In Latin America, Will was known for his coverage of social movements in Brazil, Bolivia, and Chiapas, Mexico, among other places in the region. The heated political climate in Oaxaca has raised questions about the independence of the criminal investigation. During the conflict, Attorney General Caña repeatedly labeled APPO members as “terrorists” and voiced her allegiance to Gov. Ruiz. The conflict eased only after then-President Vicente Fox ordered federal forces into Oaxaca in December to restore order and dismantle most of the barricades erected by protesters in the city center. During the Wills’ three-day visit to Oaxaca, they toured the Santa Lucía del Camino neighborhood and placed a large, black wooden cross against a white concrete wall on Juárez Avenue, where their son died. About 100 protesters accompanied the family, with some shouting, “The assassins are from the PRI!” Delia Ramírez, a 55-year-old housewife who spent time at the Santa Lucía del Camino protest camps, said she offered Will a cup of water shortly before he died. “He died trying to document the truth, and that’s something our government doesn’t appreciate,” Ramírez said. “That’s why there’s been no justice.” The Wills’ visit may produce some positive results. When they met with Caña in Oaxaca, the state attorney general announced her request that the Brad Will case–along with 10 other homicides related to last year’s conflict–be taken over by federal authorities. Murder is typically a state crime in Mexico, but cases that involve certain firearms, such as AR-15 rifles, can be considered federal crimes. Pressure from Washington may also be behind the state prosecutor’s move. A letter dated March 16 and signed by four members of the U.S. Congress–Jan Schakowsky of Illinois, Jim McGovern of Massachusetts, Hilda Solis of California, and Raúl Grijalva of Arizona–blames state police and government-affiliated agents for the deaths of 20 protesters during the Oaxaca conflict. It states that “civilian-clad municipal police officers and other state officials” were implicated in Will’s death and calls on Mexico’s attorney general, Eduardo Medina Mora, to ensure a “prompt and impartial investigation.” Local and international human rights groups, including CPJ and Amnesty International, also expressed their concern that government agents had escaped justice. Federal authorities had begun a preliminary inquiry before the state handoff. “We hope that the federal authorities now take up a serious, objective investigation,” says Miguel Ángel de los Santos, the Will family’s lawyer. In Oaxaca, he brought forward new witnesses in front of federal investigators. Among the witnesses are reporters, including Osorno of Milenio, along with individuals who saw the shootout and are just now feeling secure enough about their personal safety to testify.

But doubts linger. Key elements are still missing, namely, the weapons carried by the men who were photographed shooting in the direction of protesters. Further, domestic political pressure may stonewall the investigation. Though unpopular among many Oaxacans, Ruiz remains in office. And Mexico’s new president, Felipe Calderón, who took office on December 1, is counting on the PRI, Ruiz’s party, to support his agenda in Congress. The indictment of Oaxacan officials, a move that could discredit Ruiz, would not help Calderón gain favor among PRI legislators. If the Will case does move forward, it would represent a breakthrough in addressing crimes against journalists in Mexico, one of the region’s most dangerous places for journalists. At least six journalists have been slain in Mexico in direct reprisal for their work since 2000; CPJ is investigating the circumstances surrounding the slayings of 11 other journalists during that period. The majority of the victims covered criminal gangs, drug trafficking, or, in the case of Will, social conflicts. None of the killings have been solved. In February 2006, the Fox government created a special federal prosecutor’s office to pursue crimes against the press. But the office’s jurisdiction is limited. In the case of state crimes, which include homicide, the special prosecutor can only intervene at the request of state authorities. In the Will case, the special prosecutor provided ballistics analysis and reviewed the case file, according to Octavio Alberto Orellana Wiarco, now head of the office. “We have to respect the chain of command at the state level,” Orellana said in an interview in Mexico City. With the case now reaching the federal level, the special prosecutor’s office may be able to show some teeth. The Wills vow that if nothing is accomplished at the federal level, they will take their son’s case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, an autonomous judicial branch of the Organization of American States. “You know, when Brad was killed and a week later people were taken into custody, we assumed that everything was going along properly,” said Kathy Will. “Now, we’ve seen how they’ve muddied it up so badly. We’re outraged … there’s no way we’re giving up.” Monica Campbell is a freelance journalist based in Mexico City. |

||||

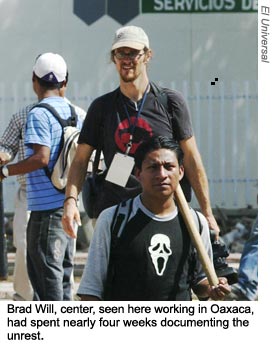

At the ready: Bradley Roland Will, a 36-year-old independent documentary filmmaker from Illinois and longtime reporter for the New York-based news Web site Indymedia. For nearly four weeks, he had fulfilled his goal of interviewing the everyday folks at the protest encampments. But on the afternoon of October 27, as he covered the barricade in the Santa Lucía del Camino municipality, on the city’s outskirts, things turned deadly. Within minutes, a street battle erupted near the protest site, down a residential side street. Will stuck close to the activists and other reporters.

At the ready: Bradley Roland Will, a 36-year-old independent documentary filmmaker from Illinois and longtime reporter for the New York-based news Web site Indymedia. For nearly four weeks, he had fulfilled his goal of interviewing the everyday folks at the protest encampments. But on the afternoon of October 27, as he covered the barricade in the Santa Lucía del Camino municipality, on the city’s outskirts, things turned deadly. Within minutes, a street battle erupted near the protest site, down a residential side street. Will stuck close to the activists and other reporters. Ballistics reports show that the two bullets that hit Will came from the same weapon, Canseco said. He estimates that the shots were fired from a distance of no more than 16 feet (5 meters), which corresponds to the distance cited in witness accounts of men shooting as they charged the protesters. None of the other men photographed alongside Zárate and Aguilar, including some who were carrying pistols and AR-15 rifles, were interrogated or detained.

Ballistics reports show that the two bullets that hit Will came from the same weapon, Canseco said. He estimates that the shots were fired from a distance of no more than 16 feet (5 meters), which corresponds to the distance cited in witness accounts of men shooting as they charged the protesters. None of the other men photographed alongside Zárate and Aguilar, including some who were carrying pistols and AR-15 rifles, were interrogated or detained.

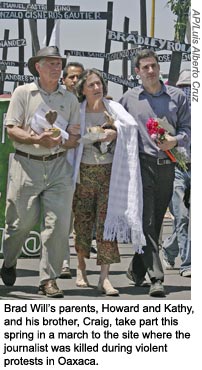

In late March, his parents, along with his older brother, Craig, went to Mexico City and Oaxaca to face officials and demand that Will’s killers face justice. “We want a real investigation,” said Kathy Will. The family hired a Mexican attorney and arrived in the country armed with photographs that appeared on the front pages of Mexican newspapers–pictures that appear to show men shooting at protesters in Santa Lucía del Camino on October 27.

In late March, his parents, along with his older brother, Craig, went to Mexico City and Oaxaca to face officials and demand that Will’s killers face justice. “We want a real investigation,” said Kathy Will. The family hired a Mexican attorney and arrived in the country armed with photographs that appeared on the front pages of Mexican newspapers–pictures that appear to show men shooting at protesters in Santa Lucía del Camino on October 27.