Uprooted journalists struggle to keep careers, independent reporting alive.

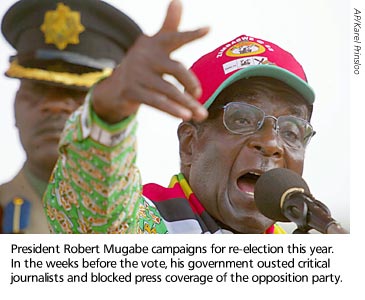

| LONDON Sandra Nyaira was on a career high when she left Zimbabwe three years ago. For her work as political editor of the country’s leading independent newspaper the Daily News, she had earned a prestigious Courage in Journalism Award from the Washington-based International Women’s Media Foundation. After traveling to the United States to receive the prize, Nyaira attended the journalism master’s program at City University in London on a scholarship. Nyaira expected to be back at her job in Zimbabwe in a year. She has yet to return. President Robert Mugabe’s government, after several unsuccessful attempts to muzzle the Daily News, finally succeeded in closing the popular daily in 2003 amid an escalating crackdown on the independent media. Family and colleagues warned Nyaira, who had already been arrested once on criminal defamation charges, that it would be foolhardy to return home. Now Nyaira lives in Somerset, England, eking out a living doing odd jobs. She wonders at age 30 whether the career at which she excelled–the one for which she once risked her freedom–will be open to her again. “We’re rotting away here,” said Nyaira, referring to her exiled Zimbabwean colleagues. At least 90 Zimbabwean journalists, including many of the nation’s most prominent reporters, now live in exile in South Africa, other African nations, the United Kingdom, and the United States, making it one of the largest groups of exiled journalists in the world, an analysis by the Committee to Protect Journalists has found. CPJ traveled to Johannesburg, South Africa, and to London, conducting 34 interviews with exiled Zimbabwean journalists, analysts, and human rights advocates. The crackdown has taken a devastating toll on Zimbabwe’s independent media. Once home to a robust press corps, Zimbabwe today has no independent daily newspapers, no private radio news coverage, and just two prominent independent weeklies. Journalists remaining in Zimbabwe are either without jobs in their profession, or they work under threat of laws that, among other things, set prison terms of up to 20 years for publishing false information deemed prejudicial to the state. Zimbabwean citizens are denied access to diverse, questioning voices at a time when the Mugabe administration, emboldened by this year’s election victory, wields power more aggressively than ever. For instance, the government’s “Operation Murambatsvina”–or “Drive Out Trash”–has destroyed the homes and livelihoods of an estimated 700,000 Zimbabweans. Done under the guise of urban renewal, the demolitions are aimed at breaking strongholds of political opposition, critics say. Journalists such as Urginia Mauluka, a former Daily News photographer beaten and detained while covering an opposition political rally in 2001, initially left for temporary respite only to delay their return as press conditions deteriorated. Others such as Abel Mutasakani, who left for South Africa in 2004, decided that only by leaving their country could they honestly report on events in Zimbabwe. And some such as Magugu Nyathi, whose newspaper, The Tribune, was shut in 2003, saw no job prospects at home. “As professionals we said ‘How do we continue?'” recalled Mutsakani, who served briefly as managing editor of the Daily News until authorities shut the paper. “I felt we had a choice. We could sit back in Zimbabwe, but that would be tantamount to surrender,” Mutsakani said. Instead, he and several colleagues went to South Africa and started the Web publication, ZimOnline. But some did not have the luxury of planning an exit. In February, three Zimbabwe correspondents for foreign media outlets–Angus Shaw of The Associated Press, Bryan Latham of Bloomberg News, and Jaan Raath of The Times of London–faced imminent arrest after being accused of spying and publishing information detrimental to the state. They left behind their homes, families, and decadeslong careers. Most journalists interviewed by CPJ have found exile a bitter experience, even as they point out that they have greater security than many colleagues back home. To penetrate competitive media job markets abroad, many must secure work permits and prove their qualifications anew. A few have secured jobs with international media outlets, but most make ends meet by working in factories, service jobs, or clerical positions. “It feels very frustrating. It is very, very difficult for a foreigner to break into mainstream journalism here,” said Conrad Nyamutata, former chief reporter with the Daily News who now lives in Leicester, England. “Very few of us have managed to get work in the field.” The emotional cost is high as well. Dingilizwe Ntuli, a former correspondent for the Sunday Times, said that adjusting to life in South Africa and leaving his family– including his ailing father who died before Ntuli could see him again–had thrust him into depression. “When you are forced to leave your country of birth, it is devastating,” said Ntuli, whose first name means “wanderer.” Though he now works again for the Times out of Johannesburg, Ntuli said he was out of the profession and disenchanted with journalism for a long period. “I felt nothing was worth living for. I gave my all to journalism and what happened? I lost my home.” Zimbabwean journalists in exile stand out in size and prestige–CPJ interviewed at least four winners of international awards for this report–but their situation is not unique. A crackdown in Eritrea and the threat of imprisonment in Ethiopia spurred flights of more than two dozen journalists to Kenya, Sudan, Europe, and North America. Communities of Burmese and Cuban journalists have been publishing in exile for years, becoming valuable sources of information on their closed societies. The exodus of Zimbabwean journalists has led to the emergence of similar media-in-exile that strive to keep news flowing about their homeland. But the station suffered a major setback this year when the Zimbabwean government succeeded in jamming its shortwave broadcasts. Jackson tried to overcome the obstacle by broadcasting on multiple frequencies, but this costly arrangement proved unsustainable and the station now sends programming online and via medium wave–methods that draw very limited audiences within Zimbabwe, though accessible to the diaspora. In Johannesburg, working in an office unmarked for security reasons, editors of ZimOnline focus on getting breaking news out of Zimbabwe and into the international community. Launched in South Africa in 2004 by Zimbabwean journalists and lawyers, the site is intended to be a news service for international media to pick up “the real Zimbabwean story,” according to its managing editor, Abel Mutsakani. “No news groups are allowed in Zimbabwe so news is not coming out from the ground,” said Mutsakani, who relies on an in-country network of sources for information. “We want to tell the story of ordinary people, especially black Zimbabweans, who suffer the most from food shortages and unemployment.” Zimbabwean law does not explicitly bar foreign publications from circulating without a license. Wilf Mbanga, a cofounder of the Daily News, used that opening to launch The Zimbabwean newspaper this year. From a small cottage in Hythe on the southern coast of England, Mbanga and his wife produce the weekly, which the couple said has a circulation of 30,000 in the United Kingdom, South Africa, and in Zimbabwe. The paper relies on largely unpaid contributions by Zimbabwean journalists in exile, as well as some anonymous reporting in the country. Mbanga, who left Zimbabwe with his wife and “one suitcase each” in 2003 to take a fellowship in the Netherlands, decided he couldn’t return home after a story he published on the militant activities of youth groups in Zimbabwe landed him the official status of “enemy of the people.” “While I was in the Netherlands I felt cut off from news at home,” he said. “I realized I would have liked a newspaper with Zimbabwean news available for the diaspora.” Media-in-exile also include Studio Seven, a radio service on the U.S.-government funded Voice of America in Washington that is staffed mainly by exiled Zimbabwean journalists. An online version of the Daily News is produced out of South Africa, while NewZimbabwe.com, featuring tabloid-style news and commentary online, is produced out of Wales. In August, Zimbabwean journalists in London launched Zimbeat.com, a news, culture, and commentary Web site. Mugabe’s government has taken notice. The state-owned Herald newspaper has published articles lambasting The Zimbabwean as “a propaganda tool for the former colonial power Britain.” Despite their growth, the exile media face serious challenges. Reliant on private donations and charitable foundations, with little or no advertising revenue, they struggle to be financially viable. And while these outlets have had success reaching the diaspora, their reach within Zimbabwe is limited to urban and affluent populations. “It is easy for the government to discredit an unknown voice coming from so far away,” said Geoffrey Nyarota, former editor-in-chief of the Daily News, who has been in exile in the United States since December 2002. Still, the exile media play an important role for the diaspora. Daniel Mololeke, who recently launched an organization of expatriate Zimbabwean journalists called the Media Reference Group, said the exile media maintain unity and build identity in the diaspora. “Media is the glue that holds Zimbabweans living outside their country together,” said Mololeke, a former lawyer and now a columnist for NewZimbabwe.com. Whether Zimbabwean journalists become entrenched in exile appears closely linked to political and economic developments at home. The majority of Zimbabwean exiles interviewed for this report told CPJ it would take not only the end of Mugabe’s rule, but reform of the country’s media laws, and a loosening of the ruling party Zanu-PF’s control for conditions to allow their return. At least some, though, say they would return now if there were job opportunities in journalism. Nyarota, the former Daily News founder and editor, said the return of exiled journalists is important to the future of democracy in Zimbabwe. Nyarota, who hopes to return home, noted that national elections in 2001, when independent media outlets still dotted Zimbabwe’s media landscape, were far more competitive than this year’s vote, when the opposition Movement for Democratic Change was nearly shut out of press coverage. Though critics accused the Zanu-PF of manipulating this year’s polls, “cheating was not necessary for them to win,” Nyarota said. The lack of media diversity, he said, ensured the ruling party’s victories. For now, financial and professional needs are plentiful, both in Zimbabwe and in the exiled community. Scores of journalists in Zimbabwe have been left unemployed in their profession by the closing of media outlets. Some exiled journalists seek funding for new and existing media projects; others need professional work, training, and education. Nyaira and some of her colleagues started the Association of Zimbabwean Journalists in the United Kingdom as a first step in addressing those needs. “There is no question– eventually people will go back,” she said. “And when we do, there will be a lot of work to do.”

|

Some of these exiled journalists left as a direct result of political persecution, others because the government’s crackdown virtually erased opportunities in the independent press. Authorities have routinely detained and harassed journalists in the past five years to quash reporting on human rights, economic woes, and political opposition to the regime, CPJ research has found. Repressive legislation such as the 2002 Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act criminalizes journalism without a government license.

Some of these exiled journalists left as a direct result of political persecution, others because the government’s crackdown virtually erased opportunities in the independent press. Authorities have routinely detained and harassed journalists in the past five years to quash reporting on human rights, economic woes, and political opposition to the regime, CPJ research has found. Repressive legislation such as the 2002 Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act criminalizes journalism without a government license. Spread as far as New Zealand, the exiled journalists have made their homes among the estimated three to four million members of the Zimbabwean diaspora. Unemployment, political violence, and human rights abuses have fueled a steady stream of emigration from Zimbabwe since the late 1990s, according to a study released this year by the International Organization for Migration. The survey of 1,000 Zimbabwean expatriates in South Africa and the United Kingdom found that most are professionals, whose absence creates “concerns for the longer-term future of Zimbabwe.” Zimbabwe’s exiled media reflect similar patterns.

Spread as far as New Zealand, the exiled journalists have made their homes among the estimated three to four million members of the Zimbabwean diaspora. Unemployment, political violence, and human rights abuses have fueled a steady stream of emigration from Zimbabwe since the late 1990s, according to a study released this year by the International Organization for Migration. The survey of 1,000 Zimbabwean expatriates in South Africa and the United Kingdom found that most are professionals, whose absence creates “concerns for the longer-term future of Zimbabwe.” Zimbabwe’s exiled media reflect similar patterns. Behind the walls of a nondescript office complex on the outskirts of London, Gerry Jackson and her staff at SW Radio are fighting to broadcast within Zimbabwe. Jackson started SW Radio in 2001, after the government closed Capital Radio, her first independent radio venture in Zimbabwe. From London, SW Radio broadcasts programs into Zimbabwe in English and in the Shona and Ndebele languages. “Radio is such a lifeline to people there who feel forgotten,” Jackson said. “It gives them a sense of creating dialogue.”

Behind the walls of a nondescript office complex on the outskirts of London, Gerry Jackson and her staff at SW Radio are fighting to broadcast within Zimbabwe. Jackson started SW Radio in 2001, after the government closed Capital Radio, her first independent radio venture in Zimbabwe. From London, SW Radio broadcasts programs into Zimbabwe in English and in the Shona and Ndebele languages. “Radio is such a lifeline to people there who feel forgotten,” Jackson said. “It gives them a sense of creating dialogue.” With shoestring budgets, limited access to government information, and few fact-checking resources, some exile media also struggle to establish credibility. Pervasive anonymity in their reports exacerbates the problem. To protect sources in Zimbabwe and family members back home, many contributors to The Zimbabwean use pseudonyms while ZimOnline does not use bylines at all.

With shoestring budgets, limited access to government information, and few fact-checking resources, some exile media also struggle to establish credibility. Pervasive anonymity in their reports exacerbates the problem. To protect sources in Zimbabwe and family members back home, many contributors to The Zimbabwean use pseudonyms while ZimOnline does not use bylines at all.