Namibian journalists worry that President Nujoma is tightening his grip on the media.

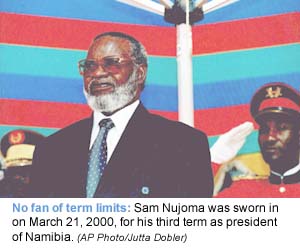

| On August 27, Namibian president Sam Nujoma, saying that he wanted to “tackle problems” at the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC), the state-owned television and radio service, appointed himself minister of information and broadcasting. Six days later in a speech at the World Development Summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, Nujoma called for an end to sanctions against his Southern Africa neighbor, Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe, whose anti-colonial rhetoric Nujoma has recently appropriated–and whose draconian crackdown on the press has been widely reported.

These two events coupled with the president’s increasingly antagonistic comments toward the media, including statements that the NBC is servicing the “enemy” and that “as journalists we all have to defend Namibia,” have left many independent journalists wondering if Nujoma is on a mission to clamp down on the media–Mugabe-style. With Nujoma’s recent comment to the BBC that when Western leaders “talk about human rights” they want to “impose European culture” on Africans, and with press freedom deteriorating in other southern African countries, journalists worry that Zimbabwe may be setting a trend for its neighbors to follow. “Right now, the Namibian press enjoys great liberties,” says Hannes Smith, editor-in-chief of the independent weekly Windhoek Observer. “But we are heading most certainly to a situation like Zimbabwe,” he adds.

Nujoma has repeatedly denounced independent journalists as “unpatriotic” or “enemies” who service former colonizers–a favorite theme of Zimbabwe’s crusade against civil society that Namibian authorities have adopted with gusto. In 1998, when the press questioned the ruling party’s–the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO)–decision to change the constitution so that Nujoma could run for a third term in office, the relationship between politicians and journalists grew even more acrimonious. And when reporters uncovered cases of official corruption, as well as human rights abuses at home and in various military engagements in other countries, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Nujoma became livid, and government ministers began withholding information from the press and accusing the media of distorting the country’s image abroad. In a great irony, Nujoma upbraided journalists at a spring 2001 UNESCO conference celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Windhoek Declaration, where he accused the media of not understanding their responsibilities. In a speech read in his absence, he claimed that journalists demand more freedom for commercial reasons, so that they may “unscrupulously engage in sensationalism, misinformation, falsifications, and lies in order to sell their products and build untouchable empires.” The public would be better served, Nujoma opined, if the press merely served as a “tool” to transmit government information.

To the dismay of Namibian journalists, Nujoma has also proved that he is willing to back up his bluster with action. In 1998, after Nujoma lashed out at the media for allegedly spreading distorted facts about the DRC conflict, the Ministry of Defense imposed a blackout on all news relating to the war. And when, in June 2000, the Windhoek Observer published an article reporting that Nujoma owned a diamond mine in the DRC–fueling speculation about Namibia’s economic incentives for participating in the conflict–Nujoma struck back with his second defamation lawsuit against the paper, which journalists believe was designed to put the paper out of business. (In 1998, he had sued the Observer for defamation over articles implying that he was corrupt.) In an even more egregious affront to press freedom, in the spring of 2001, Nujoma ordered advertising and purchasing bans on The Namibian, a paper celebrated locally and internationally for its serious and independent journalism. Officials made no attempt to hide the fact that the bans were being used to intimidate the paper economically. According to Namibian authorities, the bans, which are still in place, are necessary because of the paper’s “campaign of dangerous misinformation … which threatens the principles of unity, peace and stability that form the very foundation of our nation, and not just because the newspaper criticizes government.” Fortunately, says Gwen Lister, the editor of The Namibian, the paper has gained considerable financial strength in its nearly two decades of publishing. “If [The Namibian] had been a lesser newspaper,” she notes, “we could have been, if not crushed, then seriously affected by the advertising ban.”

Because of SWAPO’s view of the state media as a political weapon, Nujoma’s self-appointment as information minister evoked quick objection from the opposition Congress of Democrats (COD). The COD said the move could jeopardize the “right for opposition political parties and opinions to be covered in the public media.” In April 2000, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Information, and Broadcasting Gabriel Shihepo barred an NBC television news crew from covering an impromptu COD press conference held to protest the party’s loss of official opposition status. When state media show any sign of editorial independence, SWAPO ensures that it is short-lived. Ruling-party parliamentarians have blasted New Era for departing from its role of “propagating” the government’s mission, saying the paper was “biting the hand that feeds [it].” In response to such verbal intimidation, state media were conspicuously silent on Namibia’s involvement in armed conflicts, the controversy surrounding Nujoma’s third-term bid, and official corruption and mismanagement.

The occasional breakdown in control over state media that leads to the broadcast of such stories has prompted SWAPO to infiltrate the ranks of NBC at all levels, says Robin Tyson, a lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Namibia and a former manager of NBC National Radio. At the NBC, “the composition of the board of directors, the appointment of directors general and the promotion of senior managers and controllers [has] moved inexorably and ominously toward tighter government control. Party functionaries replaced professional media experts,” wrote Tyson in a recent article in The Namibian. Tyson notes that the increase in pro-SWAPO propaganda is facilitated by a lack of clear news guidelines in the Namibian Broadcasting Act of 1991, the charter governing the NBC’s operations. While the Namibian Communication Commission Act of 1992, which regulates commercial and community broadcasters, stipulates that news and current affairs must be presented in “a fair, clear, factual, accurate and impartial manner,” no such provision appears in the NBC act. The dangers of single-party control are exacerbated by the fact that the NBC has the widest reach of any news medium in the country. (The NBC broadcasts in a variety of local languages and has the most transmitters in a country with a largely illiterate population.) As head of the Information Ministry, say local journalists, Nujoma will gain even more control over state media. “What is worrying is that the so-called mechanisms of protection between president, Cabinet, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, chairman of the NBC board, the NBC board, director general [of the NBC], and staff has been withered away,” says Tyson, adding that intimidation will now be more intense, and that it will be extremely difficult for state journalists to take any line that deviates from Nujoma’s wishes. Relishing his enhanced influence, Nujoma did not wait long to confirm these fears. At a press briefing following the announced Cabinet changes, he candidly told an NBC journalist: The NBC comes “under me now. I will discipline them. You can go and tell your friends.”

The parallels with Zimbabwe are plain. Both Mugabe and Nujoma have manipulated their parties to ensure they have their way. Both have clamped down on the media to ensure that their policies are “satisfactorily” presented–and favorably received. While Nujoma’s main objective may be tighter control of the state media, he has proved that he is willing to use the economic power of the state to intimidate independent journalists as well. Though the independent Namibian press currently criticizes the president’s regime freely, Nujoma’s assumption of his new Cabinet post has fostered a growing anxiety among journalists who wonder whether the bleak horizon to the east in Zimbabwe portends a similar fate for them. “Nujoma is quite imitative of Mugabe, so one worries about the road ahead,” says The Namibian‘s Lister. “Hopefully, it won’t be that serious … at least in the very near future.” Adam Posluns is research associate for the CPJ Africa program. |

Namibia’s promise as a model democracy for southern Africa led the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to choose its capital, Windhoek, as the site of the 1991 Windhoek Declaration, a statement of principles proclaiming that “the establishment, maintenance, and fostering of an independent, pluralistic and free press is essential to the development of democracy in a nation.” But despite repeated government pledges to respect press freedom, Nujoma has become increasingly hostile toward the independent press in recent years.

Namibia’s promise as a model democracy for southern Africa led the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to choose its capital, Windhoek, as the site of the 1991 Windhoek Declaration, a statement of principles proclaiming that “the establishment, maintenance, and fostering of an independent, pluralistic and free press is essential to the development of democracy in a nation.” But despite repeated government pledges to respect press freedom, Nujoma has become increasingly hostile toward the independent press in recent years. For all the enmity and distrust of the media, Nujoma also courts the spotlight. But when he has no control over how the media project him to the audience, the result can be disastrous. Last year, Nujoma granted the South African Broadcasting Corporation an interview. But according to Mocks Shivute, Namibia’s permanent secretary of foreign affairs, information and broadcasting, when the interview aired on June 5, 2001, the program made the president look like “a furious, intolerable person” who had no respect for the rights of homosexuals, foreigners, and whites. Shivute called the broadcast “a shining example of the unscrupulous and unethical behavior of foreign journalists with hidden agendas.”

For all the enmity and distrust of the media, Nujoma also courts the spotlight. But when he has no control over how the media project him to the audience, the result can be disastrous. Last year, Nujoma granted the South African Broadcasting Corporation an interview. But according to Mocks Shivute, Namibia’s permanent secretary of foreign affairs, information and broadcasting, when the interview aired on June 5, 2001, the program made the president look like “a furious, intolerable person” who had no respect for the rights of homosexuals, foreigners, and whites. Shivute called the broadcast “a shining example of the unscrupulous and unethical behavior of foreign journalists with hidden agendas.” Namibian journalists rightly fear that Nujoma’s new Cabinet post will have more grave consequences for journalists at state-owned media outlets than for independent journalists. The ruling SWAPO’s politicization of state media organs has never been a secret. Journalists for the NBC, the Namibian Press Agency (NAMPA), and New Era, a biweekly newspaper, have long practiced self-censorship on contentious issues. As in Zimbabwe, the role of the state press as government mouthpiece is clearly the result of one party dominating the political system. For journalists, refusing to toe the official line means risking one’s job and incurring the wrath of powerful officials.

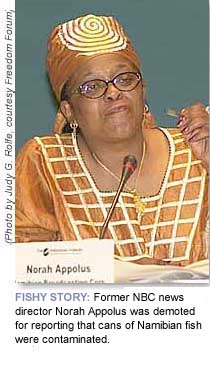

Namibian journalists rightly fear that Nujoma’s new Cabinet post will have more grave consequences for journalists at state-owned media outlets than for independent journalists. The ruling SWAPO’s politicization of state media organs has never been a secret. Journalists for the NBC, the Namibian Press Agency (NAMPA), and New Era, a biweekly newspaper, have long practiced self-censorship on contentious issues. As in Zimbabwe, the role of the state press as government mouthpiece is clearly the result of one party dominating the political system. For journalists, refusing to toe the official line means risking one’s job and incurring the wrath of powerful officials. Nora Appolus, a former NBC news director, characterized the editorial content of the state broadcaster as “sycophantic drivel.” In July 2000, Appolus was demoted to manager of training after an NBC news story reported that hundreds of cans of Namibian fish may have been contaminated. The government claimed the report was a ploy to sabotage the fishing industry, one of Namibia’s most important economic resources. Appolus’ boss, NBC board chairman Henry Uazuva Kaumbi, a pro-SWAPO stalwart, informed Appolus that her demotion was related both to the “fish” story and to the news department’s coverage of the elections in Zimbabwe, during which Zimbabwean opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai was described as “charismatic.”

Nora Appolus, a former NBC news director, characterized the editorial content of the state broadcaster as “sycophantic drivel.” In July 2000, Appolus was demoted to manager of training after an NBC news story reported that hundreds of cans of Namibian fish may have been contaminated. The government claimed the report was a ploy to sabotage the fishing industry, one of Namibia’s most important economic resources. Appolus’ boss, NBC board chairman Henry Uazuva Kaumbi, a pro-SWAPO stalwart, informed Appolus that her demotion was related both to the “fish” story and to the news department’s coverage of the elections in Zimbabwe, during which Zimbabwean opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai was described as “charismatic.” Even at this early stage, there are signs that the environment for the press is changing for the worse since Nujoma took over the information portfolio. On September 30, Nujoma banned all foreign programming at the NBC that, he said, has a “bad influence on the Namibian youth,” The Namibian reported. He told the broadcaster to replace the programs with ones that portray Namibia in a positive light. And in reaction to a September 6 Namibian cartoon that depicted Nujoma as Mugabe’s attack dog, the SWAPO Youth League called for a ban on all insults to the president and threatened they would take unspecified action to defend the Namibian leader.

Even at this early stage, there are signs that the environment for the press is changing for the worse since Nujoma took over the information portfolio. On September 30, Nujoma banned all foreign programming at the NBC that, he said, has a “bad influence on the Namibian youth,” The Namibian reported. He told the broadcaster to replace the programs with ones that portray Namibia in a positive light. And in reaction to a September 6 Namibian cartoon that depicted Nujoma as Mugabe’s attack dog, the SWAPO Youth League called for a ban on all insults to the president and threatened they would take unspecified action to defend the Namibian leader.