Understanding the players and institutions involved in the struggle for press freedom in Iran

Introduction

In April 2000, Iranian authorities launched a wide-ranging crackdown on the media following a scathing speech by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader. Khamenei accused “some papers” of “undermining Islamic and revolutionary principles.” Two days later, judicial authorities launched an aggressive campaign that resulted in the suspension of 16 publications.

In April 2000, Iranian authorities launched a wide-ranging crackdown on the media following a scathing speech by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader. Khamenei accused “some papers” of “undermining Islamic and revolutionary principles.” Two days later, judicial authorities launched an aggressive campaign that resulted in the suspension of 16 publications.

During the following months, several more publications were shut down, numerous journalists were prosecuted, and several were sentenced to prison. Although newspapers had been banned previously under the administration of President Muhammed Khatami, the scope of this crackdown was unprecedented. It underlined the tensions between reformists and conservatives in Iran today.

In this briefing, CPJ takes you behind the scenes of the struggle for press freedom in contemporary Iran. Part I surveys the recent political history of Iran. Part II surveys the repressive mechanism that conservative clerical authorities use to silence pro-reform media. Part III documents dozens of cases where journalists have been jailed and newspapers shut down for expressing viewpoints that authorities found unpalatable.

Where are they now?

Although the crackdown succeeded in silencing many reformist voices in the Iranian press (along with a few conservative voices), a number of reformist papers still operate in Iran. According to CPJ research, the main Tehran-based reformist dailies still publishing include: Iran, Kar-o Kargan, Aftab-e-Yazd, Norooz, Tosseh, Hayat-e No, and Hambasteghi (which was allowed to reopen after being suspended in August).

The remaining reformist papers have generally toned down their reporting and analysis. One foreign journalist in Iran told CPJ that while the reformist papers still advocate reform, they do not publish articles that might be perceived as “personal attacks” on government personalities. They also tend to avoid topics that might be viewed as a threat to national security.

Both reformist and conservative papers condemned the September 11 attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C. Thereafter, their coverage diverged. Many reformist papers argued, for example, that Iranian national interests required a limited dialogue with the United States on Afghanistan and the American “war on terrorism.” By and large, conservative papers rejected the idea of dealing with these issues in any forum outside the United Nations.

Part I: Political background

Iranian newspapers caught in the cross fire

Iranian newspapers caught in the cross fire

Western media coverage of Iranian politics has often described a clash between the “conservative judiciary” and the “reformist press.” While that description is not inaccurate, the actual division is more nuanced.

In the Iranian political context, a conservative is someone who opposes any modification of Iran’s theocratic regime, in which Shi’a Muslim clerics control virtually every important aspect of public life. Most of the key political institutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran, including the armed forces and the judiciary, are firmly in the hands of conservatives, led by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

“Reformist,” on the other hand, is the label commonly attached to President Muhammad Khatami and his supporters. Khatami is himself a mid-level Shi’a cleric, and the reformist agenda does not include establishing a secular state in Iran. Instead, Khatami and his supporters are mostly moderates who tend to favor incremental liberalization (notably in the areas of women’s rights and press freedom) within the basic framework of the Islamic Republic.

Since President Khatami took office in 1997, Iran’s conservative-dominated judiciary has suspended or closed at least 52 newspapers and magazines as part of a systematic campaign aimed at silencing the so-called reformist press in Iran, which generally backs President Khatami’s agenda of social and political liberalization.

Minimum Number of Newspapers Closed since 1997: 52

Minimum Number of Newspapers Closed since April 2000: 43

Number of Journalists in Jail as of September 27, 2001: 5

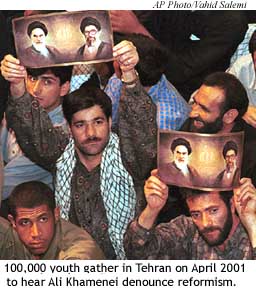

Forty-two newspapers have been closed since April 2000, when Ayatollah Ali Khamenei attacked the reformist press in his infamous April 20 speech. “There are 10 to 15 papers writing as if they are directed from one center, undermining Islamic and revolutionary principles, insulting constitutional bodies, and creating tension and discord in society,” Khamenei fulminated. “Unfortunately, the same enemy who wants to overthrow the [regime] has found a base in the country. Some of the press has become the base of the enemy.” The crackdown started two days later, when the courts banned 16 reformist newspapers and magazines. At least 43 publications have since been shut down, the vast majority reformist in their editorial orientation. Only a handful of banned newspapers have been allowed to resume publishing.

Part II: The apparatus of repression: Click here to see chart

Who controls legal affairs?

Under the Iranian Constitution, the supreme leader’s broad powers include the right to veto any legislation, to ratify the election of the president, and to appoint the head of the court system. As in the United States, the judiciary is constitutionally defined as an independent branch of government, separate from the legislative and executive branches.

The head of the judiciary must be a Muslim cleric. He serves a five-year term. The current head of the judiciary is Ayatollah Mahmoud Shahroudi.

The Assembly of Experts elects (and theoretically supervises) the supreme leader. Out of 86 seats in the assembly, conservatives currently fill 70, according to Iranian political analysts. That perpetuates a dynamic where conservative experts elect a conservative supreme leader, who in turn appoints a conservative head of the judiciary.

Not surprisingly, the head of the judiciary tends to appoint conservative judges to serve on the Press Court.

What is the Press Court?

What is the Press Court?

Tehran’s Public Court 1410, commonly known as the Press Court, hears most cases relating to journalists and publications based in Tehran. In other Iranian cities, other public courts serve the same function.

The current presiding judge of the Tehran Press Court is a young conservative jurist named Said Mortazavi.

Iran’s Press Law created a Committee for the Supervision of the Press within the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance, which is currently dominated by reformists. Committee members include a judge appointed by the head of the judiciary, the minister of culture and guidance (or his representative), a member of the Majles (Parliament), a university professor chosen by the Minister of Higher Education, a press director, a seminary cleric chosen by the Qom Seminaries Management Council, and a member of the Cultural Revolution Council.

The committee is empowered to hear complaints against journalists and newspapers and can refer complaints to the Press Court, which can summarily ban publications, and prosecute individual editors and reporters. These two functions often go hand in hand. When journalists are tried for press offenses, their publications are often suspended as well.

Journalists and newspapers are often prosecuted for publishing “lies,” “slander,” “falsehoods,” “fabrication,” “propaganda against the State,” or “insulting the leadership.”

The Press Court’s hearings are theoretically open to the public, although court sessions are often closed in practice.

How does the Press Court work?

If the Committee for the Supervision of the Press learns about a potential violation of the Press Law, the committee is supposed to notifiy the publication in question (often by fax) that it has committed a press violation. If the publication does not rectify the violation, it can be suspended and referred to the Press Court for a final decision.

Reformists dominate the committee. As a result, it rarely issued notifications of violations between 1997, when Khatami took office, and April 2000. Since then, the Press Court has tended to bypass the committee entirely, taking direct action against offending publications and journalists. As a result, the scales are now tipped in favor of the conservatives.

In most cases, the Press Court “temporarily” suspends newspapers, but very few suspended publications have been allowed to reopen.

The court often acts under Article 156 (5) of the constitution, which allows “appropriate measures in order to prevent crimes,” along with Articles 12 and 13 of the Precautionary Measures Law, a pre-revolutionary statute that allows courts to seize “instruments used for committing crimes.”

The presiding judge issues the final decisions on suspensions or bannings, while the jury recommends to the presiding judge the guilt or innocence of defendants and the severity of any penalty to be imposed. Press Court juries tend to be stacked with conservatives, and, in any case their recommendations are not legally binding.

In 2000, Amnesty International noted, “Juries in the Press Court were sometimes dismissed prior to trial and on other occasions their decisions were ignored. Press Court judgments were occasionally issued prior to jury consultation.”

The Press Court also tends to ignore the recommendations of the Ministry of Culture and Guidance, through the Committee for the Supervision of the Press, and court decisions are often not made public. Adding to the arbitrary nature of the process, the Press Court often charges publications with vague offenses such as “insulting Islamic principles” and “agitating the public,” which are not even mentioned by the Press Law.

Further complicating the picture, the Revolutionary Court often hears cases involving press violations when it has determined that the violation constitutes a “threat to the revolution.” This has created a source of tension between the Revolutionary Court and the Ministry of Culture and Guidance, which argues that press violations should only be heard in the Press Court.

Part III: Cases

CPJ has recorded the closures of the following newspapers since 1997.

(NOTE: This list is not exhaustive. For example, although some student publications are included in the cases below, the actual number of banned student publications is thought to be greater. Several unconfirmed closures are listed at the bottom of this document. CPJ continues to research these cases.)

2001

Title: Omid e-Zanjan

English: Hope of Zanjan

Type: Reformist Weekly

Suspended: October 30, 2001

Update: Allowed 20 days to file an appeal

Summary: The reformist weekly was suspended on October 30 after a court in the northwest city of Zanjan found the paper guilty of printing stories that defamed Iranian officials and the Islamic Republic, according to local sources. In addition, the editor of the paper, Ja’afar Karami, received a two-year suspended sentence. He was charged with “creating a schism among people’s ranks” and trying to pit them against one another. He was given 20 days to appeal the court’s decision.

Title: Mehr

English: Sun

Type: Cultural weekly magazine

Suspended: September 8, 2001

Summary: On or about September 8, Iran’s Special Court for Clergy, a conservative tribunal that operates independently of the regular Iranian court system, ordered the indefinite closure of the weekly magazine Mehr for “spreading lies to public opinion.” The precise reason for the closure was not clear. However, some press reports noted that the paper had recently criticized the country’s broadcast media, which is controlled by conservative forces.

Title: Hambasteghi

English: Solidarity

Type: Moderate reformist daily

Suspended: August 8, 2001

Update: Allowed to reopen on August 20

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court suspended the moderate reformist daily Hambasteghi following an unspecified complaint from the Justice Department. The closure came shortly after the paper published comments by a pro-reform member of parliament who accused Justice Department head Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi of “damaging the public interest.” The paper was closed on the same day that President Khatami gave a speech in favor of press freedom. The closure was interpreted as a snub from the generally anti-Khatami judiciary.

On August 20, the Justice Department issued a statement saying that the ban on Hambasteghi had been provisionally lifted after the paper’s managing editor acknowledged having published “mistakes” and “insulting articles.” Shahroudi reportedly approved the lifting of the ban.

Title: Farday-e-Rochan

English: Bright Tomorrow

Type: Weekly

Suspended: August 4, 2001

Summary: Judicial authorities revoked the license of the weekly Farday-e-Rochan, based in the western town of Zanjan, for allegedly publishing false and defamatory articles. The state news agency IRNA reported that conservative organizations had filed several complaints against the publication.

Title: Arman

English: Ideal

Type: Student magazine (Yazd University)

Suspended: June 2001

Summary: On or about June 26, judicial authorities in the towns of Fallah and Ghani Pour ordered the Yazd University magazine Arman closed. The closure reportedly stemmed from complaints against the paper made by unspecified Islamic and cultural groups in Iran.

Title: Nowsazi

English: Renovation

Suspended: May 9, 2001

Summary: The state news agency IRNA reported on May 9 that Tehran’s Press Court had suspended the reformist daily Nowsazi. The court claimed that Nowsazi editor Hamid Reza Jalaiepour was not “competent” to publish the paper. The court further alleged that Jalaiepour was the publisher of other banned papers that published “criminal” material. No further details were provided. Prior to the ban, Nowsazi had only published four editions. A Nowsazi staffer told Agence France-Presse that the paper received a fax from the Justice Department indicating that the paper’s license had been withdrawn.

Title: Kavir

English: Desert

Type: Student magazine (Shahid Rajai University)

Suspended: May 9, 2001

Summary: On May 9, the conservative daily Jomhuri-e-Eslami reported that Kavir, a publication of the Islamic Society of Tehran’s Shahid Rajai University, had been banned for “printing an offensive article in which God has been put on trial.” Press reports stated that the offending article was titled “Trial of the Universal Creator,” and officials said the article carried an “indecent tone and insulting interpretations.” No further details were provided.

Title: Amin-e-Zanjan

English: Zanjan’s Faithful

Type: Provincial weekly (Zanjan, west of Tehran)

Suspended: April 25, 2001

Summary: On April 25, the state news agency IRNA reported that a local court had banned the weekly Amin-e-Zanjan for “sowing seeds of discord.” The court also said that the paper’s content was likely “to provoke riots in the city.” The paper’s director and other staff members were charged with “disrupting security and tranquility.” It was not clear what particular articles prompted the ban.

Title: Qarnieh

English: Cornea

Type: Medical school journal

Suspended: March 2-3, 2001

Summary: Citing local press reports, the state news agency IRNA reported on March 3 that a press supervisory committee at Tehran Medical University had banned the university journal Qarnieh for a period of six months. The action apparently stemmed from an article and cartoon that had recently appeared in the journal; no further details were available.

Title: Jameah Madani

English: Civil Society

Type: Weekly

Suspended: March 18, 2001

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court ordered the closure of the pro-reform weekly Jameah Madani. State-controlled television reported that the action was taken because Jameah Mandani and three other publications that were closed the same day had committed “numerous and continuous violations of the law.” No further details were provided.

Title: Mobine

English: Clear

Type: Weekly

Suspended: March 18, 2001

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court ordered the closure of the weekly Mobine. State television reported that the action was taken because Mobine and three other publications that were also shut down on May 18 had committed “numerous and continuous violations of the law.” No further details were provided.

Title: Doran-e-Emrooz

English: Modern Times

Type: Daily

Suspended: March 18, 2001

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court ordered the closure of the pro-reform daily Doran-e-Emrooz, Justice Department authorities announced. State television reported that the action was taken because Doran-e-Emrooz and three other publications that were closed the same day had committed “numerous and continuous violations of the law.” No further details were provided.

Title: Payam-e-Emrooz

English: Today’s Message

Type: Monthly

Suspended: March 18, 2001

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court ordered the closure of the pro-reform monthly Payam-e-Emrooz. State television reported that the action was taken because Payam-e-Emrooz and three other publications that were closed the same day had committed “numerous and continuous violations of the law.” No further details were provided.

Title: Harim

English: Sanctity

Type: Conservative weekly

Suspended: March 8, 2001

Summary: Iran’s Press Court suspended the conservative weekly newspaper Harim for allegedly “defaming” President Muhammad Khatami. The closure reportedly stemmed from an article titled “The Slogans of Mr. K,” which chided the president for allegedly breaking campaign promises to establish the rule of law and a civil society in Iran.

Title: Hadis

English: Conversation

Type: Reformist weekly

Suspended: January 28, 2001

Update: Resumed publishing in May or June 2001

Summary: Hadis, a weekly paper based in the western town of Ghazvin, was suspended by a local court after its editor, Naghi Afshari, was arrested and accused of publishing “insulting” and “critical” articles and cartoons about the Iranian judicial system. The paper resumed publishing in May or June 2001.

Title: Kiyan

English: Entity

Type: Reformist, philosophical, and literary monthly

Suspended: January 17, 2001

Summary: On January 17, Iranian state radio and television announced the closure of the monthly cultural and intellectual magazine Kiyan. Judge Saeed Mortazavi, head of Tehran’ Press Court, claimed the magazine had “published lies, disturbed public opinion and insulted sacred law.” The closure was based on complaints filed by Prosecutor General Abbassali Alizadeh. No specific offending articles were cited.

2000

Title: Mihan

English: Homeland

Type: Reformist Weekly

Suspended: October 23, 2000

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court banned the weekly reformist newspaper Mihan for failing to print its business addresses in the paper and for illegally using the logos of banned publications.

Title: Sobh-e-Omid

English: Morning of Hope

Type: Reformist Weekly

Suspended: October 23, 2000

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court banned the weekly reformist newspaper Sobh-e-Omid for failing to print its business addresses in the paper and for illegally using the logos of previously banned publications.

Title: Sepideh-e-Zendegi

English: The Twighlight of Life

Type: Reformist Weekly

Suspended: October 23, 2000

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court banned the weekly reformist newspaper Sepideh-e-Zendeghi for failing to print its business addresses in the paper and for illegally using the logos of previously banned publications.

Title: Bahar

English: Spring

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: August 8, 2000

Update: Remains closed

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court ordered the closure of the popular reformist daily Bahar, published by a close aide to President Khatami. According to press reports, the newspaper was closed for “disturbing public opinion.” Bahar was launched just three months prior to its closure.

Title: Cheshmeh Ardebil

English: The Spring of Ardebil

Type: Reformist weekly

Suspended: August 7, 2000

Summary: Iran’s Press Court suspended the pro-reform weekly Cheshmeh Ardebil for a period of four months. The paper was accused of “disturbing public opinion” and “insulting Islamic sanctities.” No further details were available.

Title: Tavana

English: Capable

Type: Satirical weekly

Suspended: August 5, 2000

Summary: The state news agency IRNA reported that the Justice Department had ordered the satirical weekly Tavana closed for publishing “defamatory articles against officials,” the agency reported. According to press reports, the closure stemmed from published caricatures that top Iranian officials deemed insulting. According to an August 20 New York Times article, the paper “was banned after publishing a caricature of President Mohammad Khatami, who is himself a reformer. But it showed him without his clerical turban and robe. That, the court said, “amounted to defamation.”

Title: Gunagoun

English: Variety

Type: Reformist weekly

Suspended: July 25, 2000

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court ordered the closure of the reformist weekly Gunagoun, claiming that the paper had violated Iranian law in that it was merely a continuation of several newspapers that had already been banned. According to the state news agency IRNA, the closure came a day after the court summoned Gunagoun editor Fatemeh Farahmandpour to answer charges of “insulting the regime’s officials, anti-Islamic propaganda, and the dissemination of false news.” Court authorities arrived in the afternoon, ordered the occupants of the building to leave immediately, and sealed it according to IRNA. The court ruling charged that Gunagoun closely resembled the suspended pro-reform papers Jameah, Tous, Neshat, and Asr-e-Azadegan.

Title: Bayan

English: Expression

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: June 25, 2000

Summary: The Special Court for Clergy, a conservative tribunal that operates independently of the regular Iranian court system, ordered the Tehran daily Bayan to cease publishing in order to prevent it from committing unspecified new “crimes.” Cleric Ali Akbar Mohtashemi, a former interior minister and aide to President Muhammad Khatami, ran the daily. No reason was given for the move, but press reports said the court cited the Iranian Constitution, which states that “the judiciary is entrusted with taking suitable measures to prevent the recurrence of crime.”

Title: Mellat

English: Nation

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: May 22, 2000

Update: Ban lifted in early May 2001

Summary: Iranian judicial authorities banned the pro-reform daily Mellat one day after the publication of its maiden issue. The reason for the closure was unknown. In early May 2001, the paper was authorized to resume publication, according to the Society for Defending Press Freedom, a local advocacy organization.

Title: Ham-Mihan

English: Compatriots

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: May 16, 2000

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court ordered the closure of the moderate daily Ham-Mihan for allegedly publishing unspecified false accounts and offending Islamic principles. Former Tehran mayor Gholamhussein Karbaschi ran the newspaper.

Title: Sobh-e-Emrooz

English: Today’s Dawn

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 27, 2000

Update: Remains closed

Summary: Judicial authorities banned the daily Sobh-e-Emrooz without providing any justification. The authorities had previously ordered Sobh-e-Emrooz‘s closure on April 24, but the ban was reversed that same day.

Title: Mosharekat

English: Cooperation

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 27, 2000

Update: Remains closed

Summary: In a crackdown by conservative forces on the reformist press, the reformist daily Mosharekat was ordered closed by judicial authorities. Authorities did not publicly state their justification for closing the paper, which was edited by President Muhammad Khatami’s brother, Muhammad Reza Khatami.

Title: Ava

English: The Voice

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 27, 2000

Update: Remains closed

Summary: In a crackdown by conservative forces on the reformist press, a press court banned the Isfahan weekly Ava for “publishing false news with the intent of disturbing public opinion,” among other charges. The case was based on complaints by a number of government institutions, including the Intelligence Ministry, the Revolutionary Guards (an elite military force under the direct control of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei), and the Special Court for Clergy in Qom.

Title: Jebheh

English: Front

Type: Conservative

Suspended: April 29, 2000

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court ordered the closure of the conservative weekly Jebheh, according to a report by Iranian state radio. No specific reason was cited for the closure, although Iran observers interpreted it as an attempt by conservative authorities to demonstrate their impartiality in the wake of wide-scale closures of reformist and liberal publications.

Title: Asr-e-Azadegan

English: Era of the Free

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Update: Remains closed

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist daily Asr-e-Azadegan and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

Title: Fat’h

English: Victory

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Update: Permanently closed on July 31, 2001

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist daily Fat’h and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

On July 31 the state news agency IRNA reported that a Tehran Appeals Court had confirmed the ban on Fat’h. It stated that the paper was banned for publishing “defamation and lies” about the judiciary, the Revolutionary Guards, and other state institutions.

Title: Aftab-e-Emrooz

English: Today’s Sunshine

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist daily Aftab-e-Emrooz and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

Title: Arya

English: Arya

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Update: Ban reversed on May 8, 2001

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist daily Arya and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

An appeal court reversed the ban on May 8.

Title: Gozaresh-e-Ruz

English: Daily Report

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist daily Gozaresh-e-Ruz and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

Title: Bamdad-e-No

English: New Dawn

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist daily Bamdad-e-No and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

Title: Payam-e-Azadi

English: Message of Freedom

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist daily Payam-e-Azadi and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

Title: Azad

English: Free

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist daily Azad and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

Title: Payam-e-Hajar

English: Message of Hajar

Type: Reformist weekly

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist weekly Payam-e-Hajar and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

Title: Aban

English: Aban

Type: Reformist weekly

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Update: Ban lifted July 27, 2001

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist weekly Aban and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

The ban on the paper was lifted on July 27, 2001.

Title: Arzesh

English: Value

Type: Reformist weekly

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist weekly Arzesh and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

Title: Iran-e-Farda

English: Tomorrow’s Iran

Type: Reformist monthly

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Update: Remains closed

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist monthly Iran-e-Farda and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

Title: Akhbar Eqtesad

English: Economic News

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: April 23-24, 2000

Summary: Between April 23 and 24, judicial authorities ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist daily Akhbar-e-Eqtesad and 12 other newspapers and magazines for “continuing to publish articles against the bases of the luminous ordinances of Islam.” The clampdown came three days after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei launched a scathing tirade against the reformist press. According to an official press release, the newspapers were closed in order to “prevent them from committing new offenses, from affecting society’s opinions, and [from] arousing concern among the people.”

1999

Title: Khordad

English: Spring

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: November 27, 1999

Update: Remains closed

Summary: Iran’s Special Court for Clergy ordered the closure of the reformist daily Khordad. The closure came as part of the high-profile trial of former interior minister Abdullah Nouri, the paper’s publisher. The charges against Nouri, which included defaming “the system,” disseminating false information and propaganda against the state, and insulting religious leaders, were based on various articles published in Khordad. Nouri was sentenced to five years in prison and barred from practicing journalism for five years. He was subsequently jailed at Tehran’s Evin Prison.

Title: Panjshanbeha

English: Thursdays

Type: Weekly

Suspended: October 11, 1999

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court suspended the weekly Panjshanbeha after managing editor Jaleh Oskoui was charged with publishing allegedly false and “unethical” material. The charges against Oskoui stemmed in part from the paper’s coverage of a controversial play whose script had been published in a student newsletter. Authorities deemed the play blasphemous. They were apparently also displeased with a Panjshanbeha article about the closure of a number of acting schools. Panjshanbeha was suspended pending the conclusion of all legal proceedings against Oskoui.

Title: Neshat

English: Happiness

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: September 5, 1999

Update: Permanently closed

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court ordered the closure of the popular reformist daily Neshat for “insulting the sacred decrees of Islam and the supreme leader,” the latter a reference to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The closure followed the publication an article that questioned the use of capital punishment in Islam and a letter from an opposition figure who challenged the authority of Ayatollah Khamenei and urged him to distance himself from hard-liners in the Iranian regime.

Title: Salam

English: Peace

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: July 7, 1999

Status: Remains closed

Summary: The Special Court for Clergy ordered the indefinite closure of the reformist daily Salam one day after it published an alleged secret memo written by a former intelligence agent. In the memo, Said Emami (also known as Said Eslami) advised his superiors to crack down on the Iranian press. In June, Emami reportedly committed suicide in prison. He had been jailed in connection with the 1998 assassinations of several dissidents and writers.

The closure of Salam, coupled with parliament’s preliminary approval of a restrictive new press bill on July 6, triggered a wave of student protests and riots unparalleled since the Islamic revolution of 1979. On August 4, the Special Court for Clergy imposed a five-year ban on Salam.

Title: Zan

English: Woman

Type: Reformist, women’s daily

Suspended: April 6, 1999

Summary: An Islamic revolutionary court banned the reformist women’s daily Zan after it published a New Year’s message from Farah Diba, widow of the late Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, along with a satirical cartoon about the practice of making murderers pay so-called blood money. The cartoon depicts a man begging an armed criminal to spare him and kill his wife instead, since less blood money is demanded for a woman’s life than for a man’s. Hojatoleslam Gholamhossein Rahbarpour, head of the Revolutionary Court, was quoted as saying that “publishing a caricature in which blood money, one of the main judicial and religious principles of Islam, is ridiculed [must be viewed as a] direct insult.” Rahbarpour added that the publication of Farah Diba’s message was a “blatant anti-revolutionary act.” Justice Department head Ayatollah Muhammad Yazdi referred to Faezah Hashemi, Zan‘s publisher, a member of parliament, and the daughter of former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, as a “counter-revolutionary,” adding, “That’s why the Revolutionary Court is in charge of her case.”

1998

Title: Jameah Salem

English: Healthy Society

Type: Monthly

Suspended: September 29, 1998

Status: Permanently closed on September 29, 1998

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court revoked the license of the monthly Jameah Salem for allegedly insulting the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Although the court did not cite specific news articles, local and foreign journalists speculated that the court acted in response to a story published earlier that month describing the sentiment, common among young Iranians, that the country has made little progress under the Islamic Republic.

Title: Tous

English: Tous

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: September 15, 1998

Update: License revoked September 28, 1998

Summary: Judicial authorities ordered the closure of the reformist daily Tous, effective September 16, for its “publication of articles against national security and general interests.” On September 15, Tous publisher Muhammad Sadeq Javadi-Hessar received a letter stating that Tous would remain closed until further notice, pending an investigation. Authorities sealed the Tous offices on the evening of September 15 and prevented distribution of the following day’s edition. The paper’s license was revoked on September 28.

The actions against Tous came one day after Iran’s spiritual leader, Ali Khamenei, accused “certain newspapers” of succumbing to a “Western cultural onslaught…targeting people’s faith, Islam and the revolution,” and adding that “I am giving final notice to officials to act and see which newspapers violate the limits of freedom.”

Title: Khaneh

English: House

Type: Conservative weekly

Suspended: August 5, 1998

Update: License permanently revoked on August 5

Summary: An Iranian court permanently revoked the license of the conservative weekly Khaneh two days after its managing director, Muhammad Reza Za’eri, was convicted of “insulting Islamic principles, the Iranian nation, and the values of the Islamic revolution.” Za’eri was given a six-month suspended sentence and a fine of 3 million rials (US$1000).

The charge was based on a July 15 letter to the editor criticizing the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The anonymous letter commented on the Iran-Iraq war, saying, “When I think of Khomeini, all that comes to mind are the horrifying sounds of the midnight bombs that used to fall on Tehran, and the blood of thousands of innocent young Iranians who died in that war.”

The letter also criticized Khomeini’s fatwa against British author Salman Rushdie, asking, “Do you call me to follow someone who has transformed Iran into an international terrorist state with his order to murder Salman Rushdie?”

Title: Jameah

English: Society

Type: Reformist daily

Suspended: June 10, 1998

Status: License revoked on July 23, 1998

Summary: Tehran’s Press Court ordered the closure of the liberal daily Jameah and banned its managing editor, Hamid Reza Jalaipour, from running a newspaper for one year for publishing insults and false information.

The charges stemmed from several Jameah articles that were critical of government officials. The paper quoted one officer, Brig. Gen. Yahya Rahim Safavi, commander of the Revolutionary Guards, as making threatening statements against “liberals” and “anti-revolutionaries.”

Since its launch in early 1998, Jameah had earned a reputation for provocative coverage of political and social issues in Iran. Following the June 10 ruling, the paper was allowed to continue publishing for a few weeks. On July 23, an appellate court revoked Jameah‘s publishing license, effective July 25. The court reduced the ban against Jalaipour to two months.

Reported Cases of Closed Publications Still Under Investigation:

Danestaniha

Navid-e-Esfahan

Aftab Gardaan

Avaye-Varzesh

Bazar-e-Ruz

Nakhl

Gholbangh-e-Iran

According to Agence France-Presse, the Ministry of Culture and Guidance suspended these four weeklies on June 25, 2001, pending a court hearing. The ministry, which is controlled by President Khatami, described the publications as “sensational and contrary to modesty.”

CPJ has also recorded the cases of imprisoned journalists as of October 18, 2001:

Journalists in Prison

Confirmed (5)

Hamid Jafari Nasrabadi, Kavir

Mahmoud Mojdavi, Kavir

Imprisoned: May 9, 2001

Nasrabadi, director of the Shahid Rajai University student magazine Kavir, and Mojdavi, a writer at the paper, were arrested by order of Tehran’s Press Court in connection with an alleged “indecent” article Mojdavi wrote. According to press reports, the seven-page article was titled “Trial of the Universal Creator,” in which God was put on trial. Officials said the article carried an “indecent tone and insulting interpretations.”

Emadeddin Baghi, Fat’h, Neshat

Imprisoned: May 29, 2000

Baghi, former writer for the banned daily Neshat and former member of the editorial board of another outlawed daily Fat’h, was detained during the middle of a closed-door trial on charges of publishing articles that “questioned the validity of…Islamic law,” “threatening national security, and…for spreading unsubstantiated news stories” about the role of “agents of the Intelligence Ministry in the serial murder of intellectuals and dissidents in 1998.”

The charges were based on complaints lodged by a number of government agencies, including the Intelligence Ministry, the conservative-controlled Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, and former security officials. The charges also mentioned a 1999 piece Baghi published in Neshat responding to an article criticizing the death penalty. The original article had already landed Neshat editor Mashallah Shamsolvaezin in jail. Baghi’s closed-door trial began on May 1. On July 17, Tehran’s Press Court sentenced him to five and a half years in prison. In late October, an appeals court reduced the sentence to three years. He remains in Tehran’s Evin Prison.

Akbar Ganji, Sobh-e-Emrooz, Fat’h

Imprisoned: April 22, 2000

Ganji, a leading investigative reporter for the reformist daily Sobh-e-Emrooz and a member of the editorial board of the pro-reform daily Fat’h, was detained and charged by the Revolutionary Court after participating in a controversial conference in Berlin, Germany, about the future of Iran’s reform movement. He faced prosecution in the Press Court for his report on the murders of Iranian intellectuals and dissidents in 1998, which implicated several top government officials. The Press Court case is still pending, but on January 13 2001, the Revolutionary Court sentenced Ganji to 10 years in prison, followed by five years of internal exile. In May, after Ganji had already served more than a year in prison, an appellate court reduced his punishment to six months.

It was reported, however, that the Iranian Justice Department then appealed that ruling to the Supreme Court, arguing that the appellate court had committed errors in reaching its decision to commute the original 10-year sentence. The Supreme Court overturned the appellate court’s decision and referred the case to a different appeals court. That court issued a verdict on July 16 sentencing Ganji to six years in jail. According to IRNA, the ruling was “definitive,” meaning that it cannot be appealed.

However, Abbas Safai-Fard, head of the Tehran-based Society for Defending Press Freedom, said the legal decisions were not clear. “No one as yet knows which judge or which officials of the judiciary have made this latest decision,” he was quoted by IRNA on August 7, 2001 as saying.

Abdullah Nouri, Khordad

Imprisoned: November 28, 1999

In a trial that gripped the nation, the Special Court for Clergy convicted Nouri, publisher of the reformist daily Khordad and a former vice president and interior minister, of religious dissent on November 27, 1999. The conviction was widely viewed as an attempt by conservative forces within the regime to sideline Nouri, an influential ally of reformist president Muhammad Khatami, in advance of the country’s February 2000 election. Nouri was believed to be a front-runner for the important position of speaker of Iran’s Majlis (Parliament).

The charges against him, which included defaming “the system,” insulting religious leaders, and disseminating false information and propaganda against the state, were based on news articles published in Khordad. During the trial, Nouri transfixed the nation with a poignant self-defense in which he sharply criticized the clerical establishment and called for more freedom in Iranian society. He was sentenced to five years in prison and barred from practicing journalism for five years. Khordad was closed He was subsequently jailed at Tehran’s Evin Prison.

| Hani Sabra is the researcher for CPJ’s Middle East and North Africa program. |