CPJ’s mission began 20 years ago with two volunteers, a typewriter, and a letter to Walter Cronkite.

The Committee To Protect Journalists, which has helped thousands of journalists in distress during the last 20 years, began with the plight of one writer. The Committee To Protect Journalists, which has helped thousands of journalists in distress during the last 20 years, began with the plight of one writer.

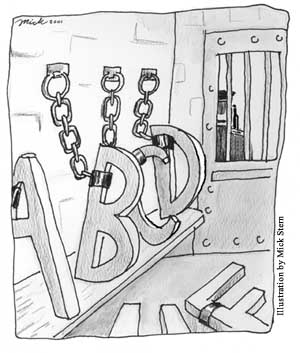

In May 1980, Alcibiades González Delvalle, a columnist for the Paraguayan newspaper ABC Color, arrived in the United States for a one-month tour sponsored by the U.S. State Department. One week into his stay, while in Kansas, González learned that a warrant had been issued for his arrest in Asunción, Paraguay’s capital. González had long been a target of the government of Gen. Alfredo Stroessner, both for his tough reporting and for his work as the head of Paraguay’s press union. The warrant was issued because of a series of investigative articles he had written about Paraguay’s Kafkaesque criminal justice system. Though facing up to three years in prison, González decided to return home and confront the government. While in the United States, González met news writer Laurie Nadel on a visit to CBS News in Manhattan. When she learned of González’s decision to return home, she called me at the Columbia Journalism Review, where I was an editor, to see if I would be interested in a story about him. I was, and she began preparing it. In the process, however, we both became concerned about what might happen to González once he returned home. We began searching for an organization that could watch over his return and make sure he didn’t simply disappear. We couldn’t find one. Neither the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, Sigma Delta Chi, nor the Overseas Press Club had any real mechanism for assisting threatened journalists outside of the United States. So we contacted newspapers and wire services and notified them of González’s imminent return to Paraguay and his expected arrest. We spoke with human rights organizations active in Latin America and with officials at the State Department. Prior to González’s departure, a UPI dispatch from New York City quoted his expectation that he would be seized as soon as he set foot on Paraguayan soil. When González arrived in Asunción, he found his family and some 40 concerned journalists waiting for him at the airport. The police–evidently worried about adverse publicity–were nowhere in sight. Early the next morning, while González and his lawyer walked to a judge’s chambers in downtown Asunción to discuss the warrant, plainclothes officers grabbed him, shoved him into a waiting taxi, and drove him to police headquarters. Later that day, he was transferred to the National Penitentiary on the outskirts of the city, where he was held incommunicado. Within days, reports of González’s arrest appeared in The New York Times and other international and domestic outlets. He was quickly moved out of solitary confinement and allowed to receive visitors. After several weeks of pressure, González was released, and soon after he returned to work at his paper. Risky region Foreign correspondents were not immune. In May 1979, for instance, as the regime of Anastasio Somoza was collapsing in Nicaragua, National Guardsmen stopped ABC News correspondent Bill Stewart at a checkpoint, forced him to kneel, and shot him point-blank in the head. Stewart’s execution, taped by his cameraman and shown on national TV in the United States, graphically showed just how perilous the practice of journalism had become in Latin America. With González’s experience fresh in mind, Laurie and I began exploring the possibility of creating an organization to help journalists in trouble. We wondered if we might somehow mobilize the great prestige and power of the U.S. press on behalf of colleagues abroad. The key, we knew, was enlisting the right people, journalists whose very names would communicate the nature and seriousness of our mission. With little hesitation, we agreed on who we’d like to be our head. In addition to being America’s most trusted journalist, Walter Cronkite had, during the Vietnam War, led a committee of journalists seeking information about reporters and photographers missing in action. We wrote him a letter describing the organization we had in mind and expressing our hope that he would agree to lead it. Two weeks later, we received a reply. As a rule, Cronkite explained, he did not lend his name to organizations in which he could not be active, and, given his schedule, he knew he could not be active in ours. But, because of the importance of our mission, he wrote, he would make an exception and serve as our honorary chairman. With Cronkite on board, we began approaching other journalists who had a record of commitment to press freedom–Anthony Lewis, Victor Navasky, and Jane Kramer. They all readily signed on. When an article about our activities appeared in The Washington Post, Dan Rather contacted us and asked if he could join; we said we thought we could find room for him. Aryeh Neier, then the executive director of Human Rights Watch, provided invaluable advice about starting a nonprofit organization. David Marash came up with a name for our group, and Alice Arlen, the head of the Alicia Patterson Foundation, gave us free space in her offices across from Grand Central Station. There, Laurie and I, together with a volunteer named Peggy Seeger, began laboring in our spare hours, trying to convert the luster of our letterhead into tangible support for journalists abroad. Fitfully, we compiled a list of sympathetic editors, correspondents, and officials. Gradually, we gathered information about individual cases–editors assaulted, reporters imprisoned, newspapers shut down. Laboriously, we typed up digests of cases and mailed them out to the names on our list, urging that protests be sent to the appropriate authorities. Months went by without any indication that we were having an effect. Then, in April 1982, Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, starting a war with Britain. The military junta in Buenos Aires, seeking to control the flow of news, arrested three British journalists on espionage charges–Simon Winchester of The Sunday Times and Ian Mather and Tony Prime of The Observer. Weeks went by without any change in their status. One day, Aryeh Neier told us that it was time to act–that the committee had been created precisely for such cases. And so Laurie, Peggy, and I typed up an urgent appeal on behalf of the three journalists. We closed with a recommendation that protest letters and telegrams be sent to Argentina’s foreign and justice ministers. When the letter was ready, we hurried over to the central post office on Eighth Avenue. Sitting on its front steps, we pasted stamps on 300 envelopes and sent them out. About 10 days later, we heard that all three journalists had been released. We had no sense of whether our efforts had played any part. Then, a few days later, Simon Winchester, safely back in England, called and told us that our appeal had been pivotal–that the Argentine government had been flooded with protests and had ordered his release. Soon after, we received a similar message from Ian Mather. For the first time, we sensed that our modest organization could in fact make a difference. Growing up The threat to journalists has changed as well. Latin America, once the world’s most dangerous region, is (with certain exceptions) today home to a vibrant press. But many other areas–China, Turkey, Central Asia, West and Southern Africa–have become more perilous, and no matter how many staff members CPJ adds, they always seem overworked. CPJ’s board, meanwhile, has expanded to the point that we sometimes worry about running out of space on our letterhead. But the spirit of commitment and dedication that helped get CPJ started remains. As for Alcibiades González, he is still writing for ABC Color in Asunción–and still irritating the government of Paraguay. Author and journalist Michael Massing is a founding member of CPJ’s board. |