Populism meets the press as Venezuela’s brash new president takes to the airwaves.

“For your information and related purposes, we are pleased to advise you that today, Wednesday December 6, 2000, at 8:00 p.m., a speech from Sir President of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela will be transmitted from the Ayacucho Hall in Miraflores Palace…”

Hugo Chávez Frías, Venezuela’s garrulous president, seems to find it ever harder to contain himself. His weekly call-in radio show “Aló, Presidente” averages four hours of conversations with adoring followers interspersed with soliloquies from the chief executive on topics such as the joys of having a girlfriend and “the revolutionary process in the universities.”

But one weekly radio show is usually not enough. When Chávez wants to talk, television and radio stations nationwide must preempt their regular programming. Chávez has used his unlimited airtime to promote the wonders of Venezuelan coffee and rally his supporters to the polls. He has urged private capital to invest in the state aluminum sector, told everyone what a fantastic day he just had, and revealed the alleged truth about 46 cases of alleged corruption in his government. Chávez is a mesmerizing speaker, and the cadenas, as his impromptu radio and television shows are called, have been wildly popular.

Two years ago, Andrés Oppenheimer of The Miami Herald predicted that Chávez would be a “pragmatic, democratically elected autocrat” along the lines of deposed Peruvian president Alberto K. Fujimori. As far as Peruvian and Venezuelan media are concerned, however, noticeable differences have emerged. Fujimori relied on his intelligence chief, Vladimiro Montesinos, to conduct a relentless campaign of harassment against the independent press that did not stop short of violence. For Chávez, the ability to broadcast directly to his supporters is the key to what he calls the “Bolivarian Revolution.”

Direct marketing

Chávez relies on direct access to his supporters, allowing him to marginalize all other institutions, including the press. He has maintained a consistently antagonistic attitude toward the media. His diatribes have to some extent undermined the credibility of the press, making local journalists vulnerable to legal and even physical attacks.

Chávez relies on direct access to his supporters, allowing him to marginalize all other institutions, including the press. He has maintained a consistently antagonistic attitude toward the media. His diatribes have to some extent undermined the credibility of the press, making local journalists vulnerable to legal and even physical attacks.

The charismatic Chávez is a former paratrooper who took part in a failed coup attempt in 1992 and then won a landslide victory in the December 1998 presidential election. He has exploited his popular support to pass referendums that dismantled Venezuela’s political infrastructure and transferred power to the presidency, all in the name of participatory democracy. (In the most recent example, voters approved Chávez’s December 3 referendum to oust the leaders of Venezuela’s opposition-controlled labor unions.)

A new Constitution, ratified in a popular referendum on December 15, 1999, extended the presidential term from five to six years, allowed the president to run for a second consecutive term, and abolished the Senate. On July 30, Venezuela held what Chávez dubbed “mega-elections,” in which a coalition of Chávez-backed parties won about 60 percent of the seats in the new, unicameral National Assembly.

Venezuela has a thriving media scene. There are two major national dailies, El Universal and El Nacional, a handful of Caracas papers, several regional publications, and a few online news sites. Three private television stations broadcast nationwide, while others deliver regional coverage. But Chávez’s direct political style inevitably makes him wary of the media’s independent influence over popular opinion. The press has vigorously criticized him, and he, in turn, has used his broadcasts to lash out at “media of the oligarchy” and to denounce foreign journalist who”dedicate themselves to the collection of garbage and throw it at the entire world.”

The most vulnerable media are radio and television, because the government controls frequency allocation. In early May, Venezuela’s top private television network, Venevisión, cancelled the popular current affairs program “24 Horas,” which had often criticized the Chávez government. The show was replaced by cartoons.

“24 Horas” host Napoleón Bravo claimed he had received anonymous threats that were traced to a state security agency, and that the network had caved in to government pressure. Although some questioned Bravo’s claims, Venevisión transferred the journalist to Florida, where he was assigned to produce five programs of a non-political nature. Not long after the Bravo incident, Venevisión eliminated all political programming.

“24 Horas” host Napoleón Bravo claimed he had received anonymous threats that were traced to a state security agency, and that the network had caved in to government pressure. Although some questioned Bravo’s claims, Venevisión transferred the journalist to Florida, where he was assigned to produce five programs of a non-political nature. Not long after the Bravo incident, Venevisión eliminated all political programming.

Over the last year, Chávez has taken to showing up unannounced at radio and television stations, particularly those that have criticized his government. On June 7, the president spent a good four hours at the offices of El Universal, talking to publisher and editor Andrés Mata Osorio and another editor. Not two weeks later, Chávez used his radio program to lash out at the newspaper for publishing a poll indicating that his popularity was diminishing. After Venezuela hosted a meeting of OPEC heads of state in late September, however, he congratulated El Universal for its coverage of the event. Meanwhile, Chávez accused CNN of “lying” and “distorting” information about the summit.

“This government doesn’t know how to handle … the possibility that many ideas can coexist in a society,” observed Sergio Dahbar, associate editor at El Nacional.

Power of suggestion

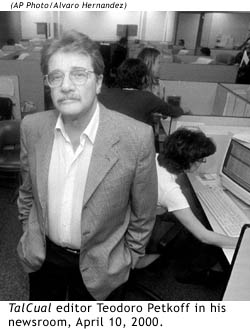

Chávez lets government officials talk freely to the press, and his administration has been relatively evenhanded in its distribution of state advertising, according to local journalists. “So far, we haven’t experienced the attacks on press freedom that we’re accustomed to here in Venezuela […],” said Teodoro Petkoff, a former Marxist guerrilla leader and planning minister who is now editor of a feisty young newspaper called TalCual. But Chávez’s constant tirades against the press have created new dangers.

Several media organizations have received bomb threats, which could be evidence that some of Chávez’s followers have interpreted the president’s fiery rhetoric as a license to attack the press. CPJ was told that while reporters used to be welcome in the working-class neighborhoods where Chávez’s support is strongest, more recently press vehicles have been vandalized and reporters harassed when they ventured into the barrios.

On May 1, pro-Chávez demonstrators assaulted a number of journalists at an election rally. A few weeks later, after the Supreme Court postponed the elections (originally scheduled for May 28), two reporters were injured covering clashes between the president’s partisans, known as chavistas, and supporters of his rival Francisco Arias Cárdenas. After these incidents, Chávez instructed his followers not to attack journalists, yet his calming message seemed less persuasive than his frequent vitriol. And when campaigning resumed in July, Chávez partisans pelted El Universal reporters with fruit and called them “journalists of the rich,” according to the paper’s editor in chief, Elides J. Rojas.

In September, a paid advertisement appeared in several papers, containing nasty attacks on several journalists and signed by the “New Bolivarian Front.” One of the journalists named in the advertisement, Marta Colomina, wrote in El Universal that the Front had been created to “exterminate the resistance that remains to the arbitrariness of those in power.” In her September 17 article, Colomina also charged that advertisers on radio programs that she hosts had received threatening phone calls from people who identified themselves as Bolivarians.

Sins of omission

While Chávez has so far been less repressive than many previous Venezuelan leaders, he has allowed longstanding government abuses of press freedom to continue. The phone lines of journalists continue to be tapped under Chávez, for example, and some journalists also claim to have been trailed by state security agents. When CPJ brought up the tapping issue with then-foreign minister José Vicente Rangel, a former journalist, he acknowledged the practice but insisted that Chávez’s government bugged “less” than previous regimes.

Whatever the case, legal protections for the press have clearly deteriorated under Chávez. When drafting Venezuela’s 26th Constitution, Chávez supporters introduced the right to “timely, truthful, and impartial information.” This provision greatly alarmed press-freedom groups, including CPJ, which argued that it could be used to justify censorship or other restrictions on information that the government deemed untimely, untruthful, or partial.

In fact, one state governor cited the new Constitution in a decree that journalists in his state should abstain from publishing or broadcasting messages that “make accusations against the legislative, executive, or judicial authorities and the citizenry in general that might expose them to public disdain or that are offensive to their honor or reputation.” (The decree was later rescinded.)

Chávez kept silent when a military judge shocked many Venezuelans by ordering the arrest of lawyer and columnist Pablo Aure Sánchez for allegedly insulting the military in a letter to El Nacional that was published on January 3, 2001. Aure’s letter described the armed forces as weak and unworthy, dismissing them as more “castrated” (castradas) than “military” (castrenses).

Chávez kept silent when a military judge shocked many Venezuelans by ordering the arrest of lawyer and columnist Pablo Aure Sánchez for allegedly insulting the military in a letter to El Nacional that was published on January 3, 2001. Aure’s letter described the armed forces as weak and unworthy, dismissing them as more “castrated” (castradas) than “military” (castrenses).

Defence minister Gen. Ismael Eliécer Hurtado Soucre denounced Aure after the letter appeared. On January 8, 2001, military intelligence agents detained the columnist at his home. Hurtado Soucre was particularly outraged by Aure’s claim that public esteem for the military had sunk so low that “we imagine them parading…in multi-colored panties.” This was a reference to an ongoing campaign in which women’s underwear (in a variety of festive hues) was being delivered anonymously to military officers in order to insult their manhood.

This reference, according to Hurtado Soucre, indicated that Aure was personally involved in the panty-raid conspiracy. After all, Hurtado Soucre argued, public statements about the campaign had only referred to “intimate garments.” How did Aure know they weren’t brassieres? The minister also told El Nacional that Aure was not the object of political persecution. “I’m not a politician, nor do I aspire to be one, nor do I want to be one,” he said. “I’m a soldier.”

Aure was released on health grounds after two days’ detention, amid a national outcry that included protests from Foreign Minister Rangel and the attorney general. Hurtado Soucre covered his bases by asking the attorney general’s office to investigate Aure. On February 2, 2001, the Supreme Court referred the case to a civil judge. That same day, the two-year anniversary of Chávez’s taking office, the president announced that Rangel would replace Hurtado Soucre as minister of defense.

Rangel thus became the first civilian to head the Ministry of Defense since democracy was restored in 1958. Chávez said the move would “have great importance in the unification of the civic and the military,” according to El Nacional. The same paper quoted Rangel, who as a journalist had frequently denounced the military, as saying that if anyone sent him panties, he would return them.

In August, journalist Pablo López Ulacio, editor of the weekly La Razón, was forced into exile in Costa Rica after a well-connected businessman named Tobías Carrero Nácar brought criminal defamation charges against him. The charges were based on La Razón‘s allegations that Carrero had received government contracts without competitive bidding. Before fleeing the country, López Ulacio boycotted all hearings held in his case, claiming that he could not possibly receive a fair trial.

The editor had a point: Manuel Quijada, the senior official responsible for judicial hiring and firing, publicly referred to him as a “defaming criminal,” and judges barred defense lawyers from gathering evidence in the United States that might have confirmed La Razón‘s allegations. The case was still pending in Venezuelan courts at press time, while López Ulacio’s lawyer had filed a petition for injunctive relief with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in Washington, D.C. (the commission granted relief on February 8). Carrero, meanwhile, apparently planned to acquire La Razón with any damages he might be awarded.

Demagogue or dictator?

Is Chávez a new and improved Latin American populist, out to transform Venezuela’s corrupt political culture for the people’s sake? Or is he an aspiring Latin American strongman who will turn repressive when his popularity starts to wane?

Is Chávez a new and improved Latin American populist, out to transform Venezuela’s corrupt political culture for the people’s sake? Or is he an aspiring Latin American strongman who will turn repressive when his popularity starts to wane?

Chávez’s popularity may already be dwindling. The president still has strong support among the Venezuelan underclass. But in the two years since the president came to power, nearly US$8 billion have left the country. In 1999, Venezuela’s gross domestic product contracted by 7.2 percent. And more recently, Venezuelans have shown signs that they are tiring of their impetuous leader. Only about a quarter of eligible voters cast ballots in the December 3, referendum on replacing trade-union leadership. One recent poll found that Chávez’s approval rating had decreased from 66 percent to 42 percent since 1999.

While campaigning for the presidency, Chávez often donned military fatigues and the red beret of his old paratroop unit. Since taking office, he has appointed many military officers to his cabinet and other top government posts, including the new chief of the state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela. Chávez also launched “Proyecto Bolívar 2000,” which employs both soldiers and civilians to build up infrastructure, health, and education systems. Under this plan, over 500 “Bolivarian” schools have already been established. All of them feature military training in their curricula.

In recent years, the three dominant social institutions in Venezuela, as in many Latin American countries, have been the Catholic Church, the press, and the army. Chávez has tried hard to discredit the first two. While he professes devout Catholicism and claims that God supports his revolution, Chávez has attacked Church leaders who criticized his government, labeling them “degenerate priests” and “Pharisees.” Chávez has also cut traditionally generous state support for the Catholic Church, and slashed budgets for Catholic schools. On December 15, El Nacional quoted the president as saying, “The institutions most loved by Venezuelans are the National Armed Forces, above the Church and the media.”

Then there is Chávez’s outright adoration for Fidel Castro. During the aging revolutionary’s five-day visit to Venezuela in October, the two leaders signed a deal in which Venezuela agreed to sell discounted oil to Cuba in exchange for medical services and other in-kind payments. They also played baseball together, and chatted for four hours on Chávez’s radio program (whose name was pluralized for the occasion, to “Aló, Presidentes”).

Then there is Chávez’s outright adoration for Fidel Castro. During the aging revolutionary’s five-day visit to Venezuela in October, the two leaders signed a deal in which Venezuela agreed to sell discounted oil to Cuba in exchange for medical services and other in-kind payments. They also played baseball together, and chatted for four hours on Chávez’s radio program (whose name was pluralized for the occasion, to “Aló, Presidentes”).

Castro’s visit upset many Venezuelans, along with U.S. officials, who were already irritated by Chávez’s comment that their US$1.3 billion anti-drug package for Colombia would lead to the “Vietnamization of the entire Amazon region.” In preparation for the OPEC heads-of-state meeting in September, Chávez met with Col. Muammar al-Qaddafi in Libya, and became the first world leader to call on Iraqi president Saddam Hussein since the end of the Gulf War. These gestures have gone down badly in the U.S. press. And bad U.S. press, in turn, has angered Chávez.

On November 3, The Washington Post ran an editorial under the headline “The Next Fidel Castro,” warning that Chávez “is a strongman who controls the biggest oil reserves outside the Middle East, who supplies the United States with a good chunk of its energy imports, and who seems intent on spreading his brand of anti-Americanism throughout the region.” In response, a miffed Chávez denounced the Post piece as “full of lies, manipulative, opportunistic, irresponsible, and false.” At the same time, he ruefully admitted that Venezuela was not really in a position to reject the United States, which is both the largest single client for Venezuelan oil and a leading investor in the country’s domestic economy. “We’re obligated to maintain and take good care of our relations with the United States, which are condemned to be good,” Chávez said.

Chávez’s understanding of international realpolitik provides a certain security guarantee to the local press, according to Manuel Alfredo Rodríguez, a columnist for El Universal and La Razón. “Press freedom is more or less respected, because [to restrict it] would create universal alarm. [Chávez] is walking on a razor’s edge.”

It is true that the Venezuelan media’s worst fears about Chávez have not materialized. “There are people who are going to commit suicide if a dictatorship doesn’t come here, because they’ve been predicting it for two years,” said TalCual editor Petkoff. Chávez can be commended for tolerating dissent without resorting to repression. After two years under his rule, journalists are still publishing biting attacks on the president, and there is no evidence of a campaign to strip the media of its independence.

Yet the effects of Chávez’s relentless rhetoric should not be underestimated. He has managed to discredit the press and instill aggression towards it among the population in general. Broadcast media were already prone to self-censorship because the government controlled their licenses. Now they stand to lose advertisers whose expensive airtime is preempted whenever Chávez feels the need to address the nation. And the Constitution’s “truthful information” clause hangs over the press like a sword of Damocles: at any time, the government could pass legislation to codify it as criminal law.

So far, the Bolivarian revolution has been great copy. But if all revolutions eat their young, Venezuelan journalists had better hope that Chávez doesn’t get too hungry.

Marylene Smeets is CPJ’s Americas program coordinator.

The Freedom Forum funded CPJ’s 2000 mission to Venezuela