Dangerous Assignments

Not many radio stations would segue from Barry Manilow singing “Copacabana” to a call-in discussion on the role of the military in national life, but on Jakarta’s Safari FM (97.4) that kind of eclectic programming is an everyday occurrence.

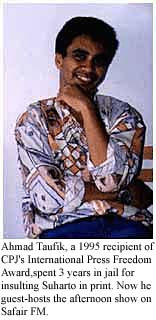

On a recent Wednesday afternoon, for example, magazine reporter and former political prisoner Ahmad Taufik was hosting a two-hour segment of Safari’s late afternoon talk show, “Wacana Jakarta,” (“Jakarta Discourse”) heatedly working over the military, racial tensions, press freedom, and a range of other issues with a guest from opposition leader Megawati Sukarnoputri’s political organization. A steady stream of listeners called in to add their views; the breaks were filled with the sounds of Kenny G. and Suzanne Vega.

“This is reformasi radio, man. We say what we want,” enthused Sri Megawati Kurniadi, a 24-year-old announcer who was engineering Taufik’s segment.

With the spirit of reformasi (reform) seemingly everywhere in Indonesia these days, the staff of Safari FM is trying to distill the spirit behind the catch-all term for political reform and change into a radio station format. Safari FM, once a mainline commercial station, operates on a shoestring budget and the belief that radio can be revolutionary in a country marred by crisis, poverty, and low literacy rates. It is now run by committed young broadcasters who want to open the country’s electronic media in the same way that a wave of unrestricted reporting is transforming the nation’s print media in the aftermath of the resignation of President Suharto last May.

“At first the students and others did not believe that radio can be revolutionary,” said program director Nor Pud Binarto. “But radio is free. It is everywhere. This can change the people. I really believe that.”

Binarto has tried to test his radio revolution theory before. As host of “Jakarta Round-Up,” the country’s first current-affairs radio call-in show, on the air from 1991 to 1994, he claimed 2.3 million listeners on Trijaya, a major radio station. Binarto used the relative openness of the early 1990s to challenge the Suharto government. But he went too far when he invited Goenawan Mohamad, the editor of the popular newsweekly Tempo, to discuss the government’s sudden closure of the magazine in 1994. Goenawan delivered an on-air denunciation of the government’s action against what had been the country’s most popular magazine; within days, Binarto’s radio career was on hold and his program was by the station’s management under government pressure.

After his show went off the air, Binarto bounced around the radio business for the next few years, setting up commercial stations and trying to do public affairs programming at several stations, with little success. Finally, on May 21 — the day that Suharto left office — he got his chance. The station’s owner, Jakarta businessman Purnomo, gave Binarto the keys to Safari FM, which had been broadcasting light jazz and business news. “Mr. Purnomo gives me full creative control,” Binarto said. “This is my radio station now, and we want to do politics, because the problem in Indonesia now is politics, not business. We have to defend our new freedom using the radio.”

At Safari, they are the children of reformasi,” said Wimar Witoelar, a well-known Indonesian television commentator who, like Binarto, was banished from the air by the Suharto regime in 1994. “They can say what they like for now, because no one wants to go against this trend of reform and liberalization.”

Safari FM broadcasts from two cramped studios inside Purnomo’s residential compound in South Jakarta. There is an air of controlled chaos, as programming changes from moment to moment. For example, a spontaneous on-air campaign to feed squatter families recently generated hundreds of donated 50-kilo bags of rice, some of which are stacked in a corner of the studio, awaiting distribution.

Safari FM broadcasts from two cramped studios inside Purnomo’s residential compound in South Jakarta. There is an air of controlled chaos, as programming changes from moment to moment. For example, a spontaneous on-air campaign to feed squatter families recently generated hundreds of donated 50-kilo bags of rice, some of which are stacked in a corner of the studio, awaiting distribution.

The station has a staff of four reporters and two announcers, and a signal that covers all of Jakarta. A series of hosts — like Taufik, who was jailed for three years starting in 1994 for insulting Suharto in print — volunteer their time to handle the late afternoon talk show. Binarto himself hosts the daily morning show from 6 to 9 a.m., during which he and actor Butet Kartagasa, a frequent guest, poke fun at Jakarta’s elite. The rest of the time, jazz and easy listening music fill the air, punctuated by periodic calls from reporters on their cell phones as they scour the city for demonstrations, human rights news, and commentary on the unfolding drama of reformasi.

A new kind of radio news has begun to emerge in Jakarta. In recent years, broadcast outlets were hamstrung by political considerations; forced to carry Indonesia state news broadcasts throughout the day, local radio stations stagnated. Those requirements have been eased considerably now, and at Safari FM, Binarto hopes to train a new generation of radio broadcasters who eventually will learn how to do serious radio journalism.

It will likely be an uphill battle. The deepening Indonesian economic crisis has stripped the station of almost all commercial spots. Binarto says that it may take a year or more to develop an audience large enough to attract cash-strapped advertisers.

“We survive now on the idea,” said Sri Megawati Kurniadi. “It is long hours and very low pay, but we will stay at it.” Binarto himself frequently goes without his salary. He spends most nights on a mattress in a tiny room next to his broadcast studio. A pair of microphones sits on a nearby table, in case he needs to broadcast from his makeshift bedroom. Binarto has never been happier. “I love my job. I love my radio station,” he said. “We are making something new.”