| |

|

It did not take long for the Hong Kong Journalists Association to serve notice on Executive Secretary Tung Chee-hwa that it would be watching his office closely. On July 10, just days after the handover of Hong Kong to China by the British, the HKJA sent Tung a letter criticizing perceived “favorable treatment” given to official Chinese state news agencies in coverage of the handover. The group complained that China Central Television was given special access to some of Tung’s early official appearances. “If Chinese official media have privileges in reporting, then news and information will very likely be held in the hands of the official media, seriously threatening press freedom,” said the letter, signed by HKJA’s chair, Carol Lai. It was the kind of outspoken approach that has become the hallmark of the HKJA. Currently in its 29th year, with some 500 members, it is the largest press association in the territory and has lobbied consistently for the continuation of Hong Kong’s free press under Chinese rule. The group says it will tolerate no backward movement in the battle for free expression. In their letter, the journalists urged Tung to “make efforts to preserve the existing media coverage system, which is based on fairness for all involved.” In response, Tung’s office called the incident a misunderstanding. |

| HKJA vice chairman Liu Kin-ming, a frequent and vocal critic of Beijing, said it is the association’s responsibility to remain engaged with the new administration of Tung Chee-hwa and to fight any effort to curb the liberties enjoyed by Hong Kong’s reporters and editors. He summed it up this way in an interview with CPJ: “To my colleagues, I ask them to please say no to the censors. To the publishers, I say, without your support we cannot win this battle. And to the outside world: Keep your eyes on Hong Kong.”

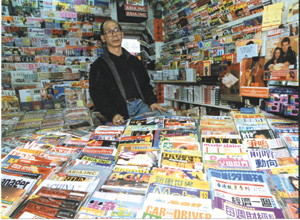

What’s at stake immediately in Hong Kong is the vibrancy not just of local media but of the vast network of regional and international press operations based in the territory. Hong Kong has long been East Asia’s English-language news media capital and more important the principal safe haven for professional, independent Chinese-language reporting about the internal political and economic affairs of the People’s Republic. Readers in the vast Chinese diaspora from Taiwan and Malaysia to British Columbia and California have depended on Hong Kong reporters and publications for decades. If this dynamic journalism culture disappears or is significantly eroded, it will have profound repercussions for all of Asia.

Hong Kong’s new leaders contend such concerns are misplaced. And on the surface, little seems to have changed. After the smoke of fireworks and celebration cleared, Hong Kong businesses resumed their usual frenetic pace, and reporters for the former colony’s 16 major daily newspapers continued to file their stories as they had before the handover. Even the most critical dailies have continued to publish without overt reprisals. “The government is functioning as normal,” Tung said in early September. “The financial market is moving. Demonstrations are continuing arguments everywhere–What has changed is that Hong Kong is now a part of China. There is a sense of pride here that this has happened, and happened without a hitch.” The resumption of Chinese sovereignty in Hong Kong has enormous geopolitical significance, signaling an end to the last vestiges of the British Empire and the emergence of China as an economic and political superpower. The people of Hong Kong have been anticipating this transition for many years, and few seasoned observers predicted dramatic upheaval in the immediate aftermath of the British withdrawal. China’s leaders and supporters steadfastly maintained prior to the transition that no major changes would take place. “One Country, Two Systems,” the phrase coined by the late Deng Xiaoping to describe the principle that would allow Hong Kong’s quasi-democratic, free-market system to coexist with the motherland’s one-party communist rule, was supposed to work this way. The Special Administration Region (SAR), as Beijing calls Hong Kong’s territory, is meant to be making money, not trouble. Beneath the calm, however, much has changed. Hong Kong today is a different place than it was before the turnover and a much different place than it was before the reality of the return began to sink in during the last several years. The climate of free expression in Hong Kong has shifted in subtle but distinct ways: In the vibrant Hong Kong press, self-censorship has become a fact of life. Newspapers owned by powerful business leaders with wide-ranging economic interests in China have become less willing to criticize Beijing. Given China’s history of tolerating little, if any, critical reporting or commentary in its national press, Hong Kong journalists have been left to wonder what might really be in store for them. “We don’t know the Chinese bottom line yet,” said one veteran reporter as she discussed the handover with colleagues inside the cavernous Hong Kong Convention Center press room two days after the fact. “I think Hong Kong journalists will be learning the Chinese bottom line.” Reporter Mak Yin Ting, sitting at the same table, quickly shot back, “Sure, we have to search for a bottom line. But why should there be a bottom line? That is an infringement on freedom. Why is it you can advocate Chinese patriotism but you cannot advocate other ideas?” What about you, a visitor asked the first journalist, will you challenge the Chinese government’s press freedom bottom line once you find it? “Unfortunately, there is a point beyond which I cannot go and I will not go. Because I do not want to be locked up,” she replied. Tung’s Friends It should come as no surprise that Tung Chee-hwa, a shipping magnate with a history of close ties to Beijing, is more interested in preserving Hong Kong’s economic vibrancy than its freewheeling journalism. But Tung’s open admiration for Singapore’s autocratic leader Lee Kwan Yew may signal more than just disinterest in free expression, presaging harsh treatment of independent journalists. Lee, the architect of Singapore’s rise to prosperity through stern governance and laissez-faire economics, is the principal proponent of the view that a free press is incompatible with “Asian values.” Lee has been openly critical of Hong Kong’s democrats. China is too powerful to be influenced by their calls for democracy, Lee told the Singapore newspaper Straits Times in June. “If you don’t believe that the Hong Kong people understand that, then you don’t understand Hong Kong,” he said. “Let’s not waste time talking about democracy…If I were a Hongkonger I would think twice before interfering in the political affairs of the mainland.” Under Lee, Singapore offers little space for democracy to flourish, and the notion of modeling Hong Kong on Singapore raises reporters’ worst fears. In May, for example, a government critic was ordered to pay senior officials a $5.7 million libel judgment for defaming them. The critic, Tang Liang Hong, called Singapore leaders liars because they had attacked him as an ethnic Chinese chauvinist. Over the years, Singapore has been the bane of journalists. Two Hong Kong-based regional publications, the Far Eastern Economic Review and The Asian Wall Street Journal have been periodically banned, and their reporters have been sued or barred from the country in disputes with Singaporean officials. In Singapore, journalists may even be prosecuted not simply for critiques of government leaders, but for the publication of mundane, accurate trade statistics prior to their authorized release by the government. Tung agrees with Singapore’s Lee on the issue of the cultural relativism of rights, supporting Lee’s view that Asian countries put a higher value on group harmony and discipline than on the individualism prized in Western cultures. “Human rights is not a monopoly of the West,” Tung told reporters in August. “When you talk about this, you have to look in terms of different countries, different historical processes, different stages of development.” When asked by reporters for his reaction to Malaysian Prime Minister Mohamad Mahathir’s call for a revision of U.N. covenants on human rights to reflect Asian values, Tung said, “I’m sympathetic to this argument. I really am.”

What is emerging from these changes may be a corporatist model in which an entrenched business elite, backed by a powerful overseer in China and led by Tung, is guaranteed an electoral majority. In such a model, it is not difficult to envision attacks on press freedom or civil liberty easily passing a parliament with only a nominal opposition presence.

But Daisy Li sees little future for the mainstream press in Hong Kong. She says her newspaper, once one of the most critical voices in Hong Kong in its coverage of China, has gone soft. Self-censorship is a fact of life in the newsroom, Li says, and she wants no part of it. In August, she left Ming Pao, as have three other top staffers and HKJA members in recent months, citing displeasure with editorial changes. “Publishers have ties to big business and to Beijing,” she said. “That just encourages self-censorship.” But instead of leaving her home in Hong Kong or her profession, Li plans to start a Hong Kong-based on-line magazine. “I’m just leaving my paper,” she explained. “I’m not leaving journalism.” The frustration Daisy Li and others feel is captured in a survey of Hong Kong journalists conducted last May by Joseph Chan, a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Over a third of those surveyed practiced some form of self-censorship in criticism of China or large Hong Kong corporations. More than half of the respondents believed that their colleagues censored themselves. In another survey of journalists undertaken by Hong Kong University in 1995, 88 percent said self-censorship was well-entrenched; 84 percent in that poll expected the situation to deteriorate under China. Eighty-six percent of Hong Kong business executives polled by the Far Eastern Economic Review shortly before the handover predicted the press would no longer be free under China. If the polling data on self-censorship are accurate, the shift to Chinese rule has already had a profound impact on Hong Kong’s journalists. The anecdotal evidence of self-censorship is abundant; journalists frequently begin a conversation on Hong Kong’s media by conceding that self-restraint now pervades the newsrooms. “It is self-censorship rather than direct intimidation that will undermine the freedom of expression in Hong Kong,” said Carol Lai of the Hong Kong Journalists Association. “We are on a dangerous path that can only lead the media to accept greater restraint. So far all the signs do not seem positive but we can only hope.” One of the most respected foreign correspondents in Hong Kong, Jonathan Mirsky, the Asia editor of the Times of London and a long-time Hong Kong resident, eloquently described the gradual tightening of controls in a piece for the Index on Censorship in January: “This is the way we live now in Hong Kong. SomeTimes Beijing barks angrily or just murmurs. More often its likes and hatreds are so well understood that, like the colonial cringe of yesteryear, local collaboration with the ‘future sovereign’ is automatic and preemptive.” Such pessimism, however, is not universal among journalists in Hong Kong. L.P. Yau, the editor in chief of the weekly Yazhou Zhoukan(Asia Week), a regional Chinese-language news magazine, is well-regarded among Hong Kong journalists. He predicted before the turnover and insists now that Chinese sovereignty presents no direct threat to press freedom. “Two months after the handover, the Hong Kong press sees no problem of political interference,” said Yau. “There is no commissar to tell any publications how to run the newsroom, nor do the readers feel any deprivation of information. There are still all kinds of criticisms of China in the media, as well as those magazines that are specialized in criticizing China.” Yau related an anecdote that he believed offered another positive measure of press freedom. At a recent banquet hosted by Taiwan’s Central News Agency’s Hong Kong bureau, the bureau’s editor in chief declared that his staff has had no problem functioning in Hong Kong since the handover. In contrast, Taiwanese journalists have had a rough time on the mainland, where they are forbidden to set up bureaus and occasionally experience government harassment. So their treatment in Hong Kong is important not only as an indicator of that territory’s press conditions, but for what it augurs for China’s relationship with Taiwan as Beijing seeks to woo Taiwan into reunification. If “One Country, Two Systems” will work in Hong Kong, the thinking goes, then it should be applied in Taiwan. “It seems that the SAR government and Beijing are determined to project an image that Hong Kong, unlike China, remains free in the wake of the handover,” said Yau. “My personal feeling is that Hong Kong is doing a good job for the time being, yet its destiny is closely related to stability in Beijing. As long as the economy is all right, Hong Kong will relish the good taste of press freedom.” The Case of Jimmy Lai: Hong Kong’s Those looking to take the measure of China’s attitude toward Hong Kong’s outspoken press may not need to wait for macroeconomic changes. Beijing has already expressed its distaste for Hong Kong’s independent journalism in the case of media magnate Jimmy Lai. The flamboyant millionaire has built a media empire in a very short time by combining investigative reporting with the flash of tabloid journalism and a reputation for no-holds-barred criticism of China.

Instead, Lai suddenly found himself without an underwriter for his offering when his sponsor, Sun Hung Kai International, a leading Hong Kong investment bank, withdrew from the deal on the eve of the listing without explanation. No other sponsor could be found, and it was widely believed that Beijing had put political pressure on bankers to torpedo Next‘s stock offering. The collapse of Lai’s IPO was a major story in Hong Kong, where business has traditionally been immune to pressure from China. Yet, with the handover just months away, the subject of China’s apparent strong-arm tactics was so sensitive that reporters had trouble finding bankers willing to comment. In a chilling coincidence, the Sun Hung Kai pullout came to light on the same day Tung Chee-hwa told CNN that it might be unlawful for Hong Kong people to make “slanderous, derogative remarks and attacks” against Chinese leaders after the handover. Tung’s comment echoed a similar threat made by Chinese Foreign Minister Qian Qichen in 1996. The Chinese government proscribes many subjects considered legitimate grist for news and commentary in the Western press including the personal lives, financial dealings, and behind-the-scenes political maneuverings of national leaders and some press freedom advocates fear that this constricted view could eventually prevail in Hong Kong, as least in regard to coverage of the Beijing government. By Beijing’s standards, many of the major news stories of the last two decades such as Kurt Waldheim’s Nazi past, Watergate, or the scandals that have tarred the ruling elite in Japan would have been inappropriate subjects for media scrutiny. Jimmy Lai is infuriating to China’s authoritarian leaders precisely because he refuses to take their cues and yet prospers by printing what his readers want. Was Jimmy Lai paying the price for insulting Li Peng and covering China with an aggressiveness that had largely disappeared from the Hong Kong press by this time? “I was left scratching my head,” said Next publisher Yeung Wai-hong, who said the underwriter had originally approached Lai enthusiastically, seeking the business. “They never told us the real reason for pulling out. The pressure that was applied must have been tremendous.” After a Next editorial criticizing Beijing’s role in the deal’s collapse, Yeung noted, China’s official Xinhua news agency, which during the colonial period functioned as a de facto Beijing embassy in Hong Kong and represented China’s interests, countered that it played no role in influencing the bankers. “We never even named Xinhua,” said Yeung. “So why are they denying?” Some analysts believe that Lai is being punished indirectly not by Beijing but by one of Hong Kong’s most powerful capitalists, Li Ka-shing. According to this theory, Li, who has vast holdings in Hong Kong and China, exacted revenge on Lai for publishing exposés about the tycoon’s personal life and examining some of his business dealings in China. Publisher Yeung would only note of Li Ka-shing that none of his many companies would advertise with Jimmy Lai’s publications. Despite Lai’s failure to launch the IPO and China’s refusal to accredit reporters from Next or Apple Daily there has been no sign that his publications will mute their voices. The companies continue to expand, getting ready to move into a vast new $100-million corporate headquarters. On June 4, Apple Daily ran a striking full-page photo of the estimated 55,000 people who showed up in Victoria Park for the annual protest against the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre. Last May, the paper ran a front-page story trumpeting Chinese President Jiang Zemin’s inclusion among CPJ’s 1997 Top Ten Enemies of the Press.

Still more disturbing are the changes at Ming Pao. (See “A Hong Kong Newspaper Softens Its Voice,” by Joseph Kahn of The Asian Wall Street Journal, page 11.) Founded in 1959 and long a favorite of Hong Kong intellectuals, Ming Pao once broke stories on China’s notorious Gang of Four and Beijing’s secret military maneuvers. Reporting on Chinese dissidents frequently led the paper, and the official Xinhua news agency often singled out Ming Pao‘s reporters for criticism. Then, in 1993, Xi Yang, Ming Pao‘s Beijing correspondent, reported on a plan by the Chinese government to sell a portion of its vast gold reserve on the world market. The story scuttled the deal by shedding light on the transaction and alerting the markets. Beijing authorities charged Xi with reporting on state secrets; he was tried and sentenced to 12 years in prison. In 1995, Malaysian-Chinese timber magnate Tiong Hew King bought the paper, and the tone of Ming Pao shifted. Stories about China began to emphasize fires, crime, and celebrities; photos got bigger; and the paper began referring to Taiwan as a “province” of China, following the style of mainland papers. An opinion writer from Shanghai who once worked for the Chinese government propaganda department joined the staff. When Xi Yang was released from prison last February, after serving three years, Ming Pao thanked China for showing “leniency.” Nothing that has happened at Ming Pao could be called direct censorship, but the hand of China or at least the perceived need to please China is manifest in these cases. “Xi Yang broke the law,” said Edgar Yuen of the pro-Beijing Hong Kong Federation of Journalists, which was formed in 1996 with China’s apparent blessing. “Of course he was punished.” Law-abiding Hong Kong journalists do not need to fear China, said Yuen, whose group was established one year before the handover. “It is a matter of getting to know one another,” he said, and of learning about China. “We are not puppets of anyone,” Yuen bristled, “and to practice self-censorship would be an insult to the profession.” Yuen and other pro-Beijing commentators argue that China would be foolish to interfere with Hong Kong’s formula for success, which generates hard currency and national pride for the mainland. Tsang Tak-sing, a member of the mainland’s People’s Congress, is editor in chief of Ta Kung Pao, one of two pro-China newspapers in Hong Kong. He told the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong last February that protecting free speech is vital. “We need the free flow of information for Hong Kong to consolidate its position as a regional and international center of financial and economic activities, so as to be useful to the modernization of China.”

If Hong Kong is to remain free, its legal lifeline is the Basic Law, the mini-constitution governing the Special Administration Region. Yet to be fully defined by the courts and open to contradictory interpretations, the Basic Law is the sole guarantor of press freedom and the rule of law for Chinese Hong Kong. Much of what happens to Hong Kong also may be determined by the attitudes that emerged from the 15th Communist Party Congress held in Beijing in September, the occasion for President Jiang Zemin to formally solidify his hold on power. And as the Congress neared, tantalizing hints of possible political reform in China began to emerge. Early in September, Liu Ji, a senior aide to Jiang, broke with a nearly decade-long moratorium on discussion of reform and called for more political liberalization to satisfy rising popular demand. “The continued rapid development of China’s economy is safeguarded by reform of the political structure,” Liu Ji said in an interview with the official China news service. “Otherwise the consequences are unimaginable.” Expressing sentiments that have not been heard in official China since the People’s Liberation Army violently crushed the democracy movement in June 1989, Liu, who is vice president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said, “When the people have enough food to eat and enough clothes to keep warm and as cultural standards increase, they will then want to express their opinions. The people wanting to take part in political thinking is a good thing, it is a sign of the prosperity and strength of the nation and is also a tide of the age that cannot be turned back.” Jiang himself hinted at political reform during his speech before the Congress. “As a ruling party, the Communist Party leads and supports the people in exercising the power of running the state, holding democratic elections, making policy decisions in a democratic manner,” Jiang said. While hardly a manifesto for free expression, Jiang’s remarks were bold by recent Chinese standards. Since 1989, Chinese officials have avoided public discussion of reform because of the assumption that official calls for easing restrictions on expression in the late 1980s contributed to the student uprising in Tiananmen Square. It is too soon to assess whether such talk of reform will lead to action. And the recent rhetoric of democracy is not likely to erase the cumulative weight of Chinese officials’ more typical public pronouncements about the press. For example, Lu Ping, Beijing’s Director of China and Macao Affairs, evoked Hong Kong journalists’ worst fears about Chinese rule last June in his warning to the press against “advocating” independence for Taiwan, Hong Kong, or Tibet. That, he said, would be a violation of national security restrictions in China. “It is all right if reporters objectively report. But if they advocate, it is action. That has nothing to do with freedom of the press.” Lu’s statements reflect a view of the relationship between speech and action whose ultimate extension is the massacre of demonstrators in Tiananmen Square. It is a position incompatible with the freedoms that Hong Kong people have enjoyed under the territory’s rule of law. Yet because the Basic Law, hammered out in often-contentious negotiations between Beijing and London after the 1984 Joint Declaration agreeing to the handover, gave half a loaf to each side in the debate over press freedom, there is uncertainty about how the two views will be reconciled in the Post-handover period. Chapter Three, Article 27, of the Basic Law, titled “The Fundamental Rights and Duties of the Residents,” provides for “freedom of speech, of the press and of publication.” The same article guarantees freedom of association, assembly, procession, demonstration, and the right to strike and form unions; there is also the right of academic freedom, and of literary and artistic creation. Framing these freedoms is Article 39, which promises to comply with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It also prohibits the introduction in Hong Kong of any restrictions incompatible with the covenant. But Article 23 seems potentially to contradict Articles 27 and 39. It instructs Hong Kong to pass laws prohibiting “treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government, or theft of state secrets,” and prohibits political organizations from establishing ties with foreign political organizations. The relationship of these three potentially contradictory clauses has never been clarified. This “is the great fascination for me as a constitutional lawyer,” Hong Kong legal scholar Yash Ghai said in a wide-ranging analysis published by Dateline: Hong Kong, a Web site devoted to the handover. “It is also the great challenge of the Basic Law.” The Basic Law will be adjudicated both in the Hong Kong courts and by a committee of the Chinese People’s Congress, notes Ghai. “You have this one document which is subject to two different regimes of interpretation.” Questions about freedom of expression in Hong Kong would ostensibly be handled by the Hong Kong courts, which are to remain independent of Beijing. But Article 23 broadly dictates that certain questions of freedom of expression fall under China’s jurisdiction. So, for example, criticism of Chinese authorities might be deemed as within the purview of Article 23. Hong Kong courts might take the line, consistent with common law, that the Basic Law is binding and creates rights and obligations. But the two bodies could have different approaches to those rights. Ghai said, “I suppose that ultimately the standing committee of the national People’s Congress will prevail because it also has a general power of interpretation of all the laws passed in the People’s Republic of China.” While such thorny interpretive and jurisdictional issues arising out of the Basic Law may take years to be fully adjudicated, Beijing’s decision to dismiss all opposition members of the elected legislature as of July 1 and to appoint a provisional legislature seemed a clear enough sign that civil liberties would suffer. “National security can be anything [Chinese government officials] say it is,” noted Robin Munro, the director of the Hong Kong office of Human Rights Watch-Asia, “and that is absolutely worrying.” Will China Rein in Will China be able to tolerate an irreverent, independent Hong Kong press climate, in which reporters, writers, commentators, and editors seek to push the boundaries? With 16 major daily newspapers, two commercial television stations, and two commercial radio stations, in addition to the seven English and Chinese-language outlets of government-owned but independently run Radio Television Hong Kong, the territory’s media have flourished under an open system. The city is home to dozens of foreign news bureaus that cover Asia out of Hong Kong because of its ease of transport and climate of freedom. The regional press is also based in Hong Kong, and news magazines such as the Far Eastern Economic Review, Asia Week, and Yazhou Zhoukancan freely publish objective reports on virtually any topic with little fear of interference. Hong Kong is one of the few places in Asia where journalists operate with almost no government control. Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia require licenses and special visas for journalists. In Hong Kong, anyone can be a journalist. There are no government-issued press cards or journalists’ visas. When press rights are threatened elsewhere in the region, Hong Kong is the place of refuge, where regional activists can meet journalists with little fear of apprehension or sanction from local authorities. Hong Kong’s role as a media center and a press freedom haven has continued with little change under the new dispensation. Human rights observer Michael Davis of Chinese University of Hong Kong has said that one important measure of press freedom will be Chinese treatment of dissident publications. “Hong Kong is the one Chinese-language press that regularly confronts Beijing,” Davis said. “Watch China Rights Forum and other such publications to see how they fare. That will be a test.” China Rights Forum, a small independent magazine published by the group Human Rights in China, has had no trouble, according to director Sophia Woodman. “As far as how things are going here, nothing seems very different,” she said in late August. In addition, according to Woodman, Beijing Spring, a Chinese dissident magazine produced in the United States, is still on Hong Kong newsstands. Writing in the International Herald Tribune in late August, Philip Bowring, the former editor of the Far Eastern Economic Review, said he saw Hong Kong’s media little changed after the transition. “Although there was an evident increase in media self-censorship in the months leading up to the handover,” Bowring wrote, “the situation has not become worse. Indeed, there are signs of greater determination now to exercise old freedoms and test the new limits. Commentators may be wary of being too rude about leaders in Beijing, but they are familiar enough with many of Mr. Tung’s acolytes to feel free to display their views, and someTimes their contempt.” While Hong Kong’s journalists may continue to tread lightly on stories about Beijing’s power elite, they already regard Tung and the provisional legislature as fair game. Many of the legislators, and certainly Tung himself, have long been subjects of scrutiny by the local media, and they may quickly establish a rhythm in their relationship quite different from that between Beijing and the mainland press. During the party congress, Apple Daily gave front-page play to the full text of a letter signed by former Communist Party leader Zhao Ziyang, who has been persona non grata in China since his ouster just before the Tiananmen Square massacre. Zhao’s letter, which called on Politburo leaders to reassess the government’s violent suppression of the pro-democracy demonstrators, provoked only stony silence from party officials. But Jimmy Lai’s newspaper once again displayed its penchant for airing Beijing’s dirty linen in public. Still, China’s record of inflexibility toward the press on the mainland raises the question of how long it will be before China acts to rein in Hong Kong’s feisty journalistic culture. With Hong Kong’s media often seeping into Southern China, will pledges to leave the broadcast news alone be honored in the longer term? In the event of social or political unrest in China, or other occurrences that could cast Beijing in a less than positive light, how will China’s leaders react if Hong Kong reporters cover the story? Beijing traditionally has been sensitive to the point of paranoia about the reporting of economic information. In 1994, Chinese reporter Gao Yu was sentenced to six years in prison for her reporting on China’s economic reforms for the generally pro-Beijing Hong Kong magazine Mirror Monthly. Last May, when UNESCO honored Gao in absentia on World Press Freedom Day, Beijing called her a “criminal” and threatened to close the UNESCO office in China. It is not hard to imagine a scenario in which powerful economic interests in Beijing bridle at critical reporting about so-called “red-chip” stocks, issued by Hong Kong-based China-owned companies. These red-chip companies, currently the darlings of the market, have defied the tumble in Hong Kong share prices that has accompanied the economic downturn in Thailand and the rest of southeast Asia. Yet some financial analysts say that many of these companies are wildly overvalued, and the lack of transparent reporting about the nature of their ownership in China make them inherently unreliable. Eventually even bullish business writers in Hong Kong could uncover potential scandals in the red-chip market. Would China regard an exposé of a scandal in a Hong Kong-traded, Beijing-owned company as a threat to “national security”? Covering the new Tung government has caused some journalists to complain about lack of access and lapse into nostalgia for the public-relations-conscious British administration. “The level of access and the culture of secrecy is already worse,” said Stephen Vines, a veteran Hong Kong reporter and editor who has worked in both the local and foreign media. “Something happens when you phone Tung’s office and you get no answer. [Former Hong Kong governor] Chris Patten was very media-savvy and media-friendly. Now there is no one you can phone up for a straight answer.” Tung’s inaccessibility is symptomatic of an executive-led government that tolerates the press as a necessary evil, Vines said. Patten lobbied long and hard to get the Hong Kong media to believe in his efforts to democratize the territory. Tung doesn’t see the press as a partner in the public discourse. “But,” cautioned Vines, “it’s not as bad as China. Not yet anyway.” Vines’ attitude seems to prevail in Hong Kong, where journalists often take to heart the old adage: Hope for the best, prepare for the worst. It is no coincidence that Hong Kong’s amazing economic growth it is the world’s eighth-largest trading economy, with a per-capita income that rivals many European countries has been accompanied by great freedom. It is that freedom to report and challenge and exchange information that has brought the world to Hong Kong as Asia’s financial and business hub. If China and Tung Chee-hwa confound the critics and allow the one-country, two-systems philosophy to flourish in Hong Kong, it may open the way toward greater press freedom for all of China. At the 15th Party Congress, Jiang set in motion the further privatization and modernization of the Chinese economy by calling for the sale of state-owned companies to private shareholders. As the Chinese government proceeds with privatization, the last vestiges of a socialist economy will likely whither away, further erasing the barriers between China and the rest of the world. The Next aspect of the Chinese system to go should be the apparatus of one-party control over information and the press. No country has built a successful, dynamic modern economy on the scale of China without allowing its people democracy and free access to information. Hong Kong knows how to be free; it can point the way for China. Success in Hong Kong will be measured in large part by freedom of information and the rule of law. At stake in Hong Kong is the health and vigor of one of the world’s great trading economies, a vital cog in the great wheel of Asian commerce and development. In that sense, the whole world will be watching and living with the outcome of Hong Kong’s drama. |

A. Lin Neumann, Asia program coordinator for CPJ, has covered Asia for 15 years.

|CPJ home | CPJ Site Contents | Report a Journalist in trouble |

Executive Secretary Tung Chee-hwa (left) with Chinese premier Li Peng in February. A running feud between Hong King media mogul Jimmy Lai and Li Peng began when Lai’s Next magazine called li Peng a “turtle egg” in a 1994 editorial. (AP Photo/Wang Xinqing, Xinhau)

Executive Secretary Tung Chee-hwa (left) with Chinese premier Li Peng in February. A running feud between Hong King media mogul Jimmy Lai and Li Peng began when Lai’s Next magazine called li Peng a “turtle egg” in a 1994 editorial. (AP Photo/Wang Xinqing, Xinhau)  Editor Daisy Li recently left her job at Ming Pao to concentrate on what she believes is a freer environment of on-line journalism. (Photo by James Leynse)

Editor Daisy Li recently left her job at Ming Pao to concentrate on what she believes is a freer environment of on-line journalism. (Photo by James Leynse)  Freelance journalist Carol Lai, the chair of the Hong Kong Journalists Association. (Photo by James Leynse)

Freelance journalist Carol Lai, the chair of the Hong Kong Journalists Association. (Photo by James Leynse)  China President Jiang Zemin (above), named one of CPJ’s 1997 Top Ten Enemies of the Press for his ongoing battle against independent journalism on the mainland, inherited the “One Country, Two Systems” philosophy from his predecessor Deng Xiaoping, but it is not clear whether he will tolerate Hong Kong’s vibrant media. (AP Photo/Enric Marti)

China President Jiang Zemin (above), named one of CPJ’s 1997 Top Ten Enemies of the Press for his ongoing battle against independent journalism on the mainland, inherited the “One Country, Two Systems” philosophy from his predecessor Deng Xiaoping, but it is not clear whether he will tolerate Hong Kong’s vibrant media. (AP Photo/Enric Marti)  Martin Lee, the chairman of Hong Kong’s Democratic Party, seen here at a pro-democracy rally at the time of the handover, lost his elected legislative Post when Beijing installed its hand-picked “provisional” legislature but remains Hong Kong’s most visible opposition leader. (Photo by James Leynse)

Martin Lee, the chairman of Hong Kong’s Democratic Party, seen here at a pro-democracy rally at the time of the handover, lost his elected legislative Post when Beijing installed its hand-picked “provisional” legislature but remains Hong Kong’s most visible opposition leader. (Photo by James Leynse)