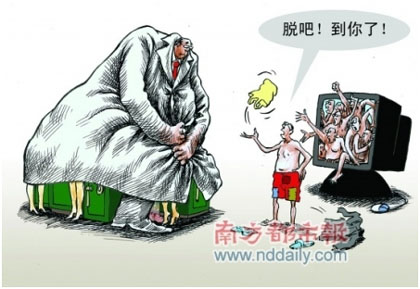

The Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress adopted a revised state secrets law on April 29. The changes, which take effect October 1, put greater onus on media and telecommunications companies to defend state secrets and cooperate with authorities investigating alleged violations of the legislation. Chinese commentators point out that while individuals are having to reveal more and more about themselves online, an official culture of concealment allows corruption to flourish unreported.

What constitutes a state secret? That remains ill-defined, and a major source of CPJ’s concern about the law: It can be used to imprison journalists and others for publishing information authorities find unwelcome, whether that information is a matter of national security or not. Obliging information technology companies to collaborate in this process codifies an existing practice: Yahoo notoriously helped authorities identify freelancer Shi Tao as the author of an e-mail detailing propaganda department instructions to the editor of an overseas Web site in 2004. Officials retroactively classified the information, leading to Shi’s conviction and 10-year prison sentence for leaking secrets abroad.

A Chinese researcher for The New York Times was also ensnared in an abusive state secrets prosecution. The Times’ Andrew Jacobs wrote last month:

It was only in 2007 that Zhao Yan, a researcher in the Beijing bureau of The New York Times, emerged from three years of detention after he was convicted of fraud. The unrelated accusations that led to his arrest—that he had revealed state secrets—were based on a Times article that correctly predicted the impending retirement of a senior Chinese leader. The state secrets charge, which was far more serious than fraud, eventually was dismissed, but not before the prosecutors introduced documents that had come from a desk in the Times office—an indication that we were never really alone.