A French judge on Tuesday authorized an anti-corruption group to pursue a complaint that questions how the leaders of three oil-rich, central African nations amassed their personal assets. One byline was absent in news media coverage: Bruno Ossébi, an online Congolese columnist and one of the few local journalists who had covered the sensitive issue. Ossébi died in February in a mysterious fire that destroyed his home and killed three others.

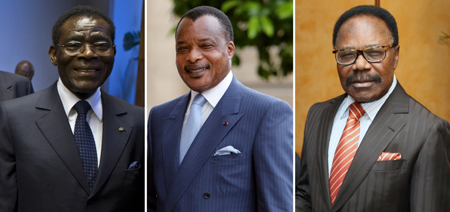

Senior French Magistrate Françoise Desset gave legal standing to Transparency International France‘s complaint alleging that French real estate, cars and bank accounts held by the ruling families of Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Republic of Congo had been acquired by appropriating public funds. The ruling allows the case to move toward trial; no allegations have been proved. Republic of Congo government spokesman Alain Akouala dismissed the ruling, telling Agence France-Presse that “in substance, there has never been anything concrete and there will never be anything concrete legally-speaking in this case.”

In separate interviews recently, the same Akouala reacted to CPJ’s report raising questions about Ossébi’s death, and declared in a Radio France Internationale program that Ossébi’s death was “an accident.” That comment seems at odds with an ongoing investigation that is supposed to determine the origin of the fire. “We want to know whether it was of criminal or accidental origin,” Public Prosecutor Alphonse Dinard Mokondzi told CPJ in our report published last month. It’s unclear how long the probe, led by a special magistrate, will take or whether its findings will be released publicly.

Ossébi edited a blog closely tracking the French lawsuit and investigating the assets of Congolese politicians. The French case has received little other coverage in the three countries; some journalists tell CPJ they have self-censored to avoid potential reprisals.

In Tuesday’s ruling, the French magistrate did not give standing to the other plaintiff in the case, Gregory Mintsa, a taxpayer from Gabon, according to Jacques Terray, vice president of Transparency International France. The ruling would have affected Ossébi who was keen on joining Mintsa as a plaintiff in the case. Mintsa, who had been the target of harassment and imprisonment since joining the complaint, could appeal, Terray said.

Nevertheless, barring a possible appeal by the French state prosecutor, the ruling could allow other anti-corruption organizations to join the complaint, said Maud Perdriel-Vaissière, a legal adviser to the plaintiffs with the French international justice network Sherpa. Those organizations include Free Actors of the Gabonese Civil Society (known by its French acronym as ACT-LIB), a Europe-based group led by French journalist and activist Bruno Ben Moubamba.

One is tempted to imagine how Ossébi would have reacted to this development had he been alive. “I know he had asked to join the complaint,” Moubamba told CPJ. “He would have been happy. This is a bit of justice for him.”