In Mexico, seven reporters have vanished in three years. Many had investigated links between public officials and drug traffickers. Are the crime groups changing tactics, or is a new type of perpetrator at work?

Posted September 30, 2008

It was nearly 8 p.m. on January 20, 2007, when Rodolfo Rincón Taracena signed off on the final version of his piece detailing a criminal gang preying on cash-machine customers in Villahermosa, capital of the southeastern state of Tabasco. The chain-smoking 54-year-old crime reporter took a call and headed out the door, telling his editor at the state’s largest daily, Tabasco Hoy, that a source was picking him up. He would be back tomorrow, he said. He never returned.

Rincón is among seven Mexican reporters who have vanished since 2005, a tally nearly unprecedented worldwide in 27 years of documentation by CPJ. The ranks of the missing include aggressive young reporters and seasoned veterans, the owner of a tiny biweekly and a crew for a major television broadcaster. Only Russia–where seven journalists disappeared in the mid-1990s while covering an insurgent war in the republic of Chechnya–has experienced a comparable period of disappearances.

Rincón is among seven Mexican reporters who have vanished since 2005, a tally nearly unprecedented worldwide in 27 years of documentation by CPJ. The ranks of the missing include aggressive young reporters and seasoned veterans, the owner of a tiny biweekly and a crew for a major television broadcaster. Only Russia–where seven journalists disappeared in the mid-1990s while covering an insurgent war in the republic of Chechnya–has experienced a comparable period of disappearances.

Mexico is already one of the world’s deadliest nations for journalists, with 21 killed since 2000, at least seven in direct reprisal for their work. But the spike in disappearances suggests a significant shift in the dangers facing the Mexican press. Throughout much of the decade, journalists in Mexico were shot in broad daylight on city streets or their bodies left in public plazas. Drug traffickers and criminal gangs are believed to have been behind the vast majority of these slayings and their very public message to the press was clear: Beware.

|

Also in this Report

|

|

| Map | |

| Recommendations | |

| Statistics | |

| Print-friendly version | |

| Versión en español |

With the rise in disappearances, analysts say, either organized crime groups are changing their tactics or, more likely, a new type of perpetrator is at work. Relatives and colleagues of several victims said in interviews with CPJ that they believe local public officials played a role in the disappearances. In at least five of these cases, CPJ found, the missing reporters had investigated links between local government officials and organized crime in the weeks before they vanished. They include reporter Alfredo Jiménez Mota, who broke major stories about the web of corruption among drug runners, police, local prosecutors, and state officials in the northern city of Hermosillo.

Although the disappearances have occurred in every corner of the country, all have happened in corridors through which billions of dollars in drugs are smuggled into the United States. In these areas, corruption has permeated all levels of society. In the case of a two-man TV Azteca crew that vanished, crime reporter Gamaliel López Candanosa was publicly accused of having ties to local traffickers–a charge the station disputed. Whatever the motive, cameraman Gerardo Paredes Pérez, a last-minute fill-in, appears to have been an inadvertent victim.

All seven of the disappearances remain unresolved today, and are without any apparent leads. Initially handled by local police, most of the cases appear to have been poorly investigated in the crucial early stages, CPJ found. José Antonio García Apac, for example, an editor in Michoacán state, was widely known to have compiled a list of allegedly corrupt officials before he vanished, yet local police never looked at that angle. Three of the seven cases are now overseen by local offices of the federal attorney general; only one is being investigated by federal authorities based in Mexico City.

Relatives of the journalists live in an emotional and legal limbo, unable  to bury their loved ones, delayed in settling estates, prevented from moving on with their lives. Colleagues tone down their investigative work or abandon it altogether as these cases grow cold and fear settles in. The cases include the disappearances of reporters Mauricio Estrada Zamora and Rafael Ortiz Martínez, both of whom dropped out of sight after reporting on crime and corruption.

to bury their loved ones, delayed in settling estates, prevented from moving on with their lives. Colleagues tone down their investigative work or abandon it altogether as these cases grow cold and fear settles in. The cases include the disappearances of reporters Mauricio Estrada Zamora and Rafael Ortiz Martínez, both of whom dropped out of sight after reporting on crime and corruption.

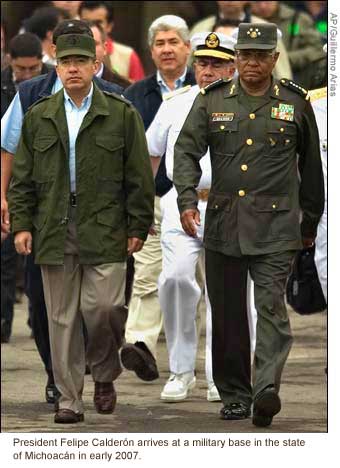

In a meeting with CPJ in June, President Felipe Calderón promised to support legislation that would make crimes against the press federal offenses. Congress is expected to debate such measures this fall. CPJ submitted specific recommendations that, among other things, would mean the cases of missing journalists would be overseen by federal prosecutors.

“The main source of danger for journalists is organized crime–and the second is the government,” said Rep. Gerardo Priego Tapia, who heads a congressional committee on violence against the press and who supports federalization of such crimes. “The worst scenario for journalists is when organized crime and the government become partners. And in many parts of this country, they are completely intertwined.”

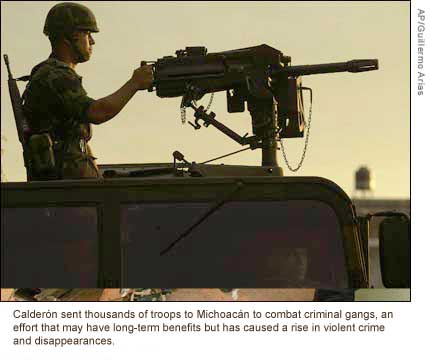

Forced disappearances have been prevalent throughout Latin America’s modern history, particularly during the 1970s and ’80s, an era marked by right-wing dictatorships and civil war. In Mexico, disappearances have reemerged as a national phenomenon. According to a 2008 investigative series in the Mexico City weekly Proceso, at least 600 people have gone missing nationwide since late 2006, when the newly inaugurated Calderón deployed the army and federal police to wage war on organized crime. While many are optimistic that Calderón’s efforts will generate long-term benefits, the campaign has disrupted the social balance, making corrupt officials more vulnerable to exposure and leading to a rise in both violent crime and the number of disappearances. In at least some missing-person cases,Proceso found evidence of government involvement.

Rincón was considered one of Tabasco’s more dogged crime reporters. The day before he vanished, the newspaper ran a two-page spread in which the reporter described illicit “drugstores,” or narcotiendas, run by traffickers. The story, which named several suspects, was accompanied by a map pinpointing these distribution centers and a photograph showing a family allegedly selling drugs. In his cash-machine story, Rincón specified where the criminals’ safe houses were located. “It was his typical exclusive,” said Roberto Cuitláhuac, the paper’s crime editor.

No witnesses ever emerged, and investigators’ one publicized lead–the discovery of human remains at a nearby ranch–did not take them to Rincón.

Olivia Alaniz Cornelio, his longtime girlfriend and a reporter at another Villahermosa daily, told CPJ that Rincón was accustomed to getting threats, but a call about a month before he disappeared had alarmed him. He didn’t offer details, Alaniz said, but he urged her to stay alert.

Alaniz is skeptical that Rincón’s disappearance is the work of drug traffickers alone. “It’s more common for narcos to send a message with their victims,” she said, noting that a decapitated head was once left on the doorstep of the Villahermosa- based El Correo de Tabasco. “There is no way that organized crime can become so powerful here and conduct their business without the help of corrupt officials. I think somebody set out to silence Rodolfo without a trace.”

based El Correo de Tabasco. “There is no way that organized crime can become so powerful here and conduct their business without the help of corrupt officials. I think somebody set out to silence Rodolfo without a trace.”

Many of the other reporters who have vanished wrote about the possible links between local authorities and organized crime. In 2005, as drug trafficking swept Mexico’s northern border states, the editors of El Imparcial, a leading daily in Hermosillo, Sonora, recruited a young reporter who had broken stories of organized crime in the neighboring state of Coahuila.

Alfredo Jiménez Mota, a 240-pound one-time boxer, was aggressive and ambitious, said his father, also Alfredo Jiménez. He went for the big names, exposing crime rings and the public officials he said were linked to them. According to his editor, Jorge Morales, he also made plenty of enemies.

Jiménez angered officials at the state attorney general’s office by hounding them about dropped investigations, and he drew the ire of the police chief when he looked into alleged links between the department and local drug traffickers, CPJ found. Morales said he often urged Jiménez to drop his byline for safety reasons, but the reporter was insistent to the point of threatening to sue El Imparcial if the newspaper did not credit his work.

In the days before his disappearance, though, Jiménez appeared rattled, and he told several colleagues that he was being followed, Morales said. On the evening of April 2, 2005, he postponed dinner plans with a co-worker so he could meet with a “nervous source,” the editor said. His parents, who have been briefed by authorities, said they were told that Jiménez went to a burger restaurant to meet the deputydirector of the local prison, Andrés Montoya García. Montoya told authorities he later gave Jiménez a ride to a convenience store, dropping him off at 10:30 p.m.

That was the last known sighting. El Imparcial said it had obtained Jiménez’s cell phone records, which show that he made calls later that night to numbers belonging to the prison official; a local deputy prosecutor named Raúl Fernando Galván Rojas; and a third person the paper could not trace.

Montoya and Galván were investigated and cleared by federal authorities, Morales said. Both resigned shortly after Jiménez disappeared and have dropped from public view. Neither could be located for comment for this story. Officials in the federal attorney general’s kidnapping unit, which has handled the case, did not respond to CPJ’s repeated requests for comment. The case is the only one of the seven that has been directly overseen by the federal attorney general in Mexico City.

The case took a startling turn in June, when Sonora Gov. Eduardo Bours made public a letter that sought to link his government to the Jiménez case. Allegedly written by one of the captors, the letter details the reporter’s supposed kidnapping, torture, and murder, and implicates several local officials, as well as the governor’s brother.

Bours vehemently denied any involvement in the case and called for a new investigation. Though Morales and Jiménez’s father doubt the letter’s credibility, they do believe that Sonoran authorities could have colluded with local crime groups in the reporter’s disappearance. Jiménez wrote about drug trafficking, Morales said, “but it all led to local authorities.”

One crime analyst notes that the spike in disappearances could simply reflect a change in tactics among crime groups. “The impact of a journalist’s death has a short duration,” says Raúl Fraga Juárez, a journalist and security expert at the Universidad Iberoamericana. “But if a journalist goes missing, uncertainty will always linger.”

Others point a finger more directly at local officials. Samuel González Ruiz, a former organized-crime prosecutor for the federal attorney general’s office and a security adviser to the United Nations, believes the disappearances could reflect the entanglement of local authorities in criminal operations. “There are parts of Mexico where you can’t distinguish between local police and criminals, and it has become very dangerous for journalists who report on this situation,” he said. While proof is scarce, he acknowledged, “I have no doubts that local police are involved in the disappearances of journalists.”

reflect the entanglement of local authorities in criminal operations. “There are parts of Mexico where you can’t distinguish between local police and criminals, and it has become very dangerous for journalists who report on this situation,” he said. While proof is scarce, he acknowledged, “I have no doubts that local police are involved in the disappearances of journalists.”

For her series of reports on the overall phenomenon of disappearances, Proceso reporter Gloria Leticia Díaz spoke to several people who said their loved ones had been dragged away by uniformed men they believed to be with the military or the police. Officials at the Public Ministry replied by saying that anyone could buy a uniform.

Map out the states and cities where journalists have gone missing and a clear pattern emerges. All worked in states that are key trafficking corridors for smuggling cocaine, heroin, and marijuana from Colombia and Mexico into the United States. Violence in Guerrero, Michoacán, and Nuevo León–three states where journalists have gone missing–has increased as powerful criminal groups, including the Sinaloa and Gulf cartels, fight for turf and retaliate against those who stand in their way, whether they are soldiers, cops, or even the doctors who attend to wounded rivals.

Until recently, Nuevo León and its wealthy capital, Monterrey, were considered safe. But in early 2007, violence spread as the drug gangs, including the Gulf cartel’s enforcement arm, Los Zetas, battled for control of Monterrey and its nearby drug route into Texas. The emergence of well-financed criminal groups brings with it a rise in corruption at many levels of society–including journalism. In a 2006 report, CPJ cited numerous professional sources as saying that journalists had accepted bribes, or “chayote,” to skew their reporting or spread drug traffickers’ messages to the press.

When a wave of execution-style murders struck Monterrey, Gamaliel López Candanosa, a correspondent for the national broadcaster TV Azteca, sprang into action. Soon, crime reporters began noticing that López, known locally as “Gama,” always seemed to arrive first at cri me scenes. In an April 2007 interview in Crucero, a local online publication, López said jealous colleagues had been spreading false rumors that he was complicit with Los Zetas.

me scenes. In an April 2007 interview in Crucero, a local online publication, López said jealous colleagues had been spreading false rumors that he was complicit with Los Zetas.

On May 10, 2007, López and camera operator Gerardo Paredes Pérez had finished a piece on the birth of conjoined twins at Hospital Universitario in Monterrey and were scheduled to head to their next assignment, a report on abused children. No one has reported seeing the journalists or their Chevy compact, marked with the TV Azteca logo, after they wrapped up the story at the hospital.

Nuevo León Prosecutor Luis Carlos Treviño Berchelman told local legislators in November 2007 that López had gone missing as a result of the reporter’s links to organized crime. Pressed by TV Azteca to present evidence supporting the charge, Treviño retracted his statement and has never again addressed the issue.

A local journalist who spoke on condition of anonymity told CPJ that in the months prior to his disappearance, López purported to be a messenger for Los Zetas, telling reporters what to cover and what to ignore. “He told me not to worry, that these were good people who wanted to work in peace,” said the journalist. “Gamaliel told me to do as they said.”

TV Azteca managers did not return repeated calls from CPJ seeking comment for this story, and relatives of López could not be located for comment. Paredes did not ordinarily work with López, and colleagues do not believe he was a target.

In Mexico, a missing-person case is generally considered a state crime. Typically, local police handle the initial investigation and then hand the case over to the state attorney general’s missing-persons unit. As with homicides, cases can move to the federal level under certain circumstances–if the victim was a public official, if the crime involved military-style weapons, or if the disappearance was linked to organized crime. But investigations can be botched–or, worse, the crimes covered up–in the initial stages, when local police are in charge.

In early 2008, Congress approved several measures designed to overhaul the criminal justice system. Witness protection programs were created, rules were established to improve the hiring and training of police officers, and forensic equipment was designated for purchase. “These are exactly the type of changes we need,” said Macedonio Vázquez Castro, a criminal law expert at the Mexico City-based Center for Criminal Policy Studies and Penal Sciences. But the system still faces massive problems, among them the fear and intimidation that criminals instill in citizens and law enforcement officials.

Vázquez said conflicts of interest inevitably arise when local police investigate cases that involve organized crime. “The situation law enforcement officials face on the ground can be extremely challenging,” Vázquez noted. “My feeling is that if there are no positive results, if the investigation is clearly going nowhere, then there is a clash of interests somewhere. I mean, what can we expect people to do when there are criminals on the loose with their guns cocked and loaded? Corruption can result from greed–or survival.”

On July 8, 2006, Rafael Ortiz Martínez, a reporter for the daily Zócalo, based in the capital city of Monclova in the northern border state of Coahuila, was last seen leaving the newsroom at about 1 a.m. He had just finished editing material for a radio news show he hosted. Somewhere in the three-minute car ride from the paper’s offices to his apartment, Ortiz and his company vehicle, a cherry-red Nissan Tsuru sedan, vanished.

Days later, Coahuila Gov. Humberto Moreira Valdés announced that there was enough evidence to believe that drug traffickers had kidnapped Ortiz in retaliation for his work. But two years later, a state police official in Monclova, speaking on condition of anonymity because he is not allowed to comment on investigations,  told CPJ, “We have no leads.”

told CPJ, “We have no leads.”

Sergio Cisneros, Zócalo‘s editor in 2006, said Ortiz did not ordinarily investigate organized crime or drug trafficking. “For safety concerns, it is the paper’s policy not to cover those issues,” Cisneros said. But journalists in Monclova told CPJ that Ortiz had recently reported on a conflict between local taxi drivers and Los Zetas.

In Ciudad Acuña–where Ortiz worked as an investigative reporter for Radio Felicidad until six months prior to his disappearance–he detailed labor abuses in nearby mines, described the workings of local prostitution rings, and named regional drug lords, said Osiris Cantú, director of the local daily Zócalo de Acuña. Friends of the reporter, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, said Ortiz received numerous death threats, some related to his criticism of a local council candidate.

Early in the investigation, authorities searched Ortiz’s home, reviewed his articles, and attempted to locate his car. But the investigation went cold. The Monclova officer claimed that Ortiz’s family and colleagues were unwilling to cooperate with investigators. Zócalo‘s new editor, Pedro Pérez, put it a different way: Interviewed by police once, he said he refused to be interviewed again after the officers in charge of the investigation told him that police had lost the original case files.

Mystery also surrounds the case of Mauricio Estrada Zamora, a crime reporter for the daily La Opinión de Apatzingán, located in the western state of Michoacán. He went missing on February 12, 2008, after leaving the paper’s offices at about 10 p.m. to head home. The next morning, his car was found parked, its doors open and engine running, in the neighboring municipality of Buena Vista Tomatlán. Estrada’s laptop and camera, along with the car’s stereo, were missing.

The investigation appeared to get off to a strong start. The Michoacán state kidnapping unit dispatched a search helicopter to Buena Vista Tomatlán. Local police interviewed Estrada’s family, including his wife and brother. They spoke to the five members of the newspaper staff working when Estrada left the office. “They asked us if Estrada had ever been threatened and about the last few articles he published,” said María de la Luz Uyuela Granado, the paper’s editor-in-chief.

Soon after, according to CPJ interviews with editors of La Opinión de Apatzingán, Estrada’s family learned that the reporter had recently been involved in a disagreement with a Federal Investigations Agency (AFI) operative, someone nicknamed “El Diablo.” The investigation, by then in the hands of the local office of the federal attorney general, appeared to slow and eventually come to a halt, the editors said.

Sara Salas, a spokeswoman for the federal attorney general, said investigators could not identify an AFI agent known as “El Diablo” or make a connection between Estrada’s disappearance and a federal agent. They dismissed any link at all to a criminal group, she said, before turning the case back to local police.

In several instances, relatives have sought to investigate cases themselves, working with civic groups and organizing friends to distribute leaflets. “Families feel alone and isolated from the authorities. There is often little contact between them,” said Coordinator Alma Díaz of the Asociación Esperanza (Hope Association), a group based in the northern state of Baja California that assists families of missing people, including that of Alfredo Jiménez Mota. “The message families get is: no body, no crime,” said Díaz. She urges relatives not to stay silent. “They can’t let fear overcome them.”

In the central-western state of Michoacán, Rosa Isela Caballero, wife of missing journalist José Antonio García Apac, is pressing authorities to step up their investigation. García, founder and editor of the Tepalcatepec weeklyEcos de la Cuenca, stopped on the way home to call his family in Morelia around 8 p.m. on November 20, 2006. Could he bring home groceries, he asked. While on the phone with his son, García was overheard responding to men asking his identify and then demanding he hang up. Sounds of García being dragged away were heard before the line went dead.

In the central-western state of Michoacán, Rosa Isela Caballero, wife of missing journalist José Antonio García Apac, is pressing authorities to step up their investigation. García, founder and editor of the Tepalcatepec weeklyEcos de la Cuenca, stopped on the way home to call his family in Morelia around 8 p.m. on November 20, 2006. Could he bring home groceries, he asked. While on the phone with his son, García was overheard responding to men asking his identify and then demanding he hang up. Sounds of García being dragged away were heard before the line went dead.

García reported regularly on organized crime in Michoacán, where drug-related violence has soared in recent years. Weeks before his disappearance, Ecos de la Cuenca published articles about violence between cartels and collusion among local police and hit men working for drug traffickers.

In an interview with CPJ, Isela, the mother of García’s six children, said she has made dozens of trips to the attorney general’s office in search of answers. She asked, for example, whether calls could be traced from García’s cell phone, which he was using when he was apparently abducted. Salas, the attorney general’s spokeswoman, said phone records turned up no leads.

Sylvia Martínez, the García family lawyer, also demanded to know if officials investigated a list García had compiled of Michoacán officials he believed were linked to organized crime. Isela said that her husband took that list to the federal organized crime unit in Mexico City in May 2006 for corroboration–a move other Michoacán reporters considered very risky considering the high level of corruption within Mexican law enforcement agencies.

Isela said that Michoacán state authorities told her that line of investigation was not followed because there is no record of García’s visit to the organized crime office. Salas said federal authorities had no comment on whether the lead was pursued. Based on other, unspecified information, she said, authorities concluded that García’s case was not connected to organized crime.

In July, Isela was informed by Michoacán state authorities that García’s case had been put on hold. “I don’t want them to forget the case,” said Isela. “More than anything, I want to know whether or not he is dead.”

Isela continues to publish Ecos de la Cuenca when she can, although it now runs mostly local government news. No longer are there stories about organized crime or anything else that could trigger controversy. “Only my husband could do that type of work,” she said. Her goal is to keep the paper alive in memory of her husband. On the upper right-hand side of each edition, she runs a small black-and-white photo of García, with a caption demanding that authorities solve the case. “This is what he would want me to do,” said Isela. She lives on about $100 a month from the paper, support from her three eldest sons, and funding from the Rory Peck Foundation, a U.K.-based press freedom group.

Bit by bit, Isela is recuperating. After long bouts with insomnia, she is sleeping through the night. She is regaining the weight she lost and is beginning to run again, something she and García did together. She is also surrounded by five sons who live with her in a small house on the outskirts of Morelia, the Michoacán capital. “They are my support network and have gotten me through this,” said Isela. One of her remaining wishes is to have a special place for remembering García. She often visits her mother-in-law’s grave and imagines that García is there as well.

In other disappearances, colleagues are shaken. At Tabasco Hoy, where Rodolfo Rincón Taracena worked, the newspaper’s staff has made adjustments. On a recent afternoon, crime editor Cuitláhuac sat in the chair Rincón once used. He and his staff of four crime reporters agreed that Rincón’s investigations were dangerous, but they also said that he took precautions. He varied his routine, did not take street cabs, and used the company car whenever possible. Today, the four reporters follow the same safeguards, but they will not follow in Rincon’s investigative footsteps.

It’s unsafe enough, said Manuel Antonio Ascencio, to be alone in a car, going down some back road. Ascencio refuses to increase the risk by undertaking an investigative piece. Fellow reporter José Angel Cintro Domínguez admitted that he once liked crime reporting because it put him in the “middle of the action.” But now he stands back and watches as organized crime in Tabasco goes unreported. “The government is supposedly fighting all of this and we are supposed to cover it,” said Cintro. “Are we supposed to just leave everything unreported?”

Cuitláhuac supplied an answer. “That,” he said, “is exactly the psychological effect the criminals want.”

Monica Campbell is a freelance writer and CPJ’s Mexico City-based consultant. María Salazar is CPJ’s senior research associate for the Americas.