In Argentina, millions of pesos in government advertising are distributed without clear rules or standards. News coverage is influenced as critics are punished and government-friendly outlets are rewarded.

RÍO GALLEGOS, Argentina

Since Néstor Kirchner became president in 2003, his administration’s advertising budget has jumped 354 percent, according to figures compiled by Poder Ciudadano, a nongovernmental organization that promotes civic participation. In effect, analysts say, Kirchner has replicated nationally what he did during his three terms as governor of Santa Cruz–imposing a system of rewards for friendly media outlets and advertising embargoes on critics. Such a system remains in place today in Santa Cruz, a province of nearly 200,000 in the southernmost tip of the Patagonia, CPJ found in a fact-finding mission conducted in August.

Known for its oil riches and breathtaking glaciers, the province was considered an outpost in national politics until Kirchner’s emergence as a popular and powerful governor. As president, he’s continued to keep a tight hold on provincial politics, handpicking close allies as gubernatorial candidates and as top appointees. Besides El Periódico Austral, the capital city of Río Gallegos has three other dailies: La Opinión Austral,the oldest paper in the province; Tiempo Sur; and Prensa Libre. Three private television stations and about four-dozen FM radio stations also compete for ads. Nearly all local media rely on government advertising revenue, putting managers under heavy pressure to avoid critical stories that could hurt their own bottom line.

“Without state advertising it is almost impossible to survive,” said Daniel Gatti, host of two radio shows on FM Abril, a Congressional candidate, and one of Kirchner’s harshest critics. Gatti, who wrote a 2003 biography of the president titled Kirchner, el Amo del Feudo (Kirchner, Lord of the Domain), said that the government “is the main advertising wallet” in Santa Cruz.

One provincial official reasons that Santa Cruz can’t be doing anything improper because there are no rules to determine what is proper. “As there are no regulations, we implement the law of supply and demand,” Roque Alfredo Ocampo, the Santa Cruz minister of government, told CPJ. He acknowledged that Ulloa’s media group and other outlets receive more money than others, but he insisted that disparities are the product of a system without rules. Provincial data reviewed by CPJ shows that Ulloa’s media group received 879,360 pesos (US$275,000) in the first five months of 2007, a figure many times higher than that of other provincial outlets.

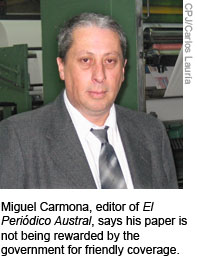

Miguel Carmona, El Periódico’s editor, denied that his paper is being rewarded as a friendly media outlet, and he downplayed any benefits the Ulloa group has derived. After all, he said, the newspaper leases its cars and facilities, and the boss himself drives a car that’s a year old. “Perhaps people are bothered by the fact that [Ulloa] is a friend of the president,” Carmona said. A request to interview Ulloa, made through Carmona, was declined.

Miguel Carmona, El Periódico’s editor, denied that his paper is being rewarded as a friendly media outlet, and he downplayed any benefits the Ulloa group has derived. After all, he said, the newspaper leases its cars and facilities, and the boss himself drives a car that’s a year old. “Perhaps people are bothered by the fact that [Ulloa] is a friend of the president,” Carmona said. A request to interview Ulloa, made through Carmona, was declined.

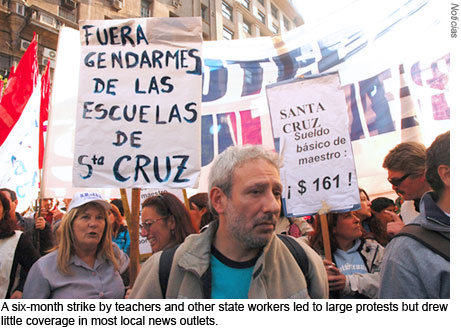

Recent events suggest a correlation between government advertising and the tone and volume of coverage, according to a CPJ analysis. A six-month strike by teachers and other state workers that began in March led to weekly protests that drew thousands into the streets. In a province ordinarily supportive of the government and the Kirchners, it was an extraordinary display.

You would not know it from much of the news coverage. El Periódico Austral and the other Ulloa media outlets ignored the conflict until it made headlines in the national press. Since then, they have played down its importance. Angered by what they perceived as censorship in the official media, demonstrators organized a boycott of cable subscription to Ulloa’s Channel 2 and staged several protests in front of El Periódico Austral. With a few exceptions on radio, other private media outlets went out of their way to avoid criticizing the government.

The crisis did highlight the emergence of highly critical FM radio stations as an alternative to the traditional press. Many citizens sought out these outlets as the only way to express their discontent, journalists said. FM News, a small privately owned station in Río Gallegos, in particular earned a reputation for uncompromising coverage. “This radio [station] turned into the people’s voice and changed the dynamic of the local media,” said Gatti about his competitors at FM News.

Rolando Vera and Hugo Moyano, FM News owners, said that they have been harassed, threatened, and persecuted because of their critical reporting. In May, the Federal Committee for Broadcasting ordered the seizure of the FM News’s equipment after national border police complained that the station’s frequency obscured their own. An injunction halted the seizure and allowed the station to continue on the air, but FM News and other local reporters believe the order came in reprisal for their burgeoning popularity.

Rolando Vera and Hugo Moyano, FM News owners, said that they have been harassed, threatened, and persecuted because of their critical reporting. In May, the Federal Committee for Broadcasting ordered the seizure of the FM News’s equipment after national border police complained that the station’s frequency obscured their own. An injunction halted the seizure and allowed the station to continue on the air, but FM News and other local reporters believe the order came in reprisal for their burgeoning popularity.

“We have given ordinary people the chance to express themselves for the first time in many years. That’s the key of our success,” Rolando Vera, co-owner of FM News, told CPJ.

Outlets such as FM News notwithstanding, the allocation of state advertising in the absence of clear rules is causing serious damage to press freedom in Argentina, CPJ found. The system may be at a pivotal point, however. In September, the Supreme Court ruled that the province of Neuquén improperly withdrew lottery and other advertising from Río Negro after the daily ran a 2002 report on corruption in the local legislature.

The court found that while the media is not entitled to state advertising, the government “cannot manipulate official advertising, distributing it or withdrawing it with discriminatory criteria.” The court ordered the government of Neuquén to present a plan for distribution of official advertising that would respect the ruling’s guidelines.

In another closely watched case, the nation’s largest magazine publisher, Editorial Perfil, filed suit in July 2006 alleging discrimination in government advertising in retaliation for the group’s critical reporting. The case is pending.

Roberto Saba, ADC’s executive director, said he is optimistic given the Río Negro ruling. The most important result, he said, would be clear and transparent legislation that would “limit governments’ discretionary authority when allocating official advertising.”

The debate has prompted Congress to consider six different bills aimed at ensuring more objective distribution of official advertising. ADC and Poder Ciudadano have urged that the reforms include moratoriums on state advertising in periods just prior to elections. Whatever legislation emerges, however, will come long after this year’s discriminatory advertising practices have accomplished their purpose at the polls.

Carlos Lauría is CPJ’s senior program coordinator for the Americas.