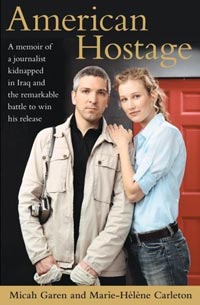

In a new book, filmmaker Micah Garen recounts his captivity in Iraq.

| U.S. documentary filmmaker Micah Garen was held hostage for 10 days in Iraq in August 2004 and released unharmed, thanks in part to the work of his fiancée Marie-Hélène Carleton. The couple spoke with CPJ about their new book, American Hostage, which recounts the ordeal.

“It was like they had set up a studio for a beheading,” Garen said. It was in just such a setting that hostages Nick Berg and Kim Sun-Il had been beheaded, their brutal deaths filmed in spring 2004. Garen had seen them on television in his Baghdad hotel room. Now it was August 17, 2004, a day Garen thought would be his last. Instead, when his captors removed the blindfold, they made him hold his press card up to the camera and state his name. Then they launched into a stream of invective in Arabic, which he did not understand. The next day, in New York, Marie-Hélène Carleton watched as her fiancé’s captors, sympathizers of radical Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, announced that if U.S. forces did not leave the holy city of Najaf, Garen would be dead within 48 hours. “For a short moment, it felt like the death of hope,” she said. Carleton put aside her despair and went to her computer to mobilize journalists to lobby for Garen’s release. Garen had first gone to Iraq in June 2003 to research a documentary. He shunned bullet-proof vests and armed guards and found it easy to work. “I wasn’t afraid of saying that I was an American,” he said. He returned with Carleton in May the following year to finish the film on the looting of archaeological sites around the southern city of Nasiriyah. “The only thing that protects you out there …[are] the principles of journalism,” Garen said. “A lot of times people are tempted to look for other protection, like, ‘I’m going to wear a bullet-proof vest. I’m going to go out in an American convoy.’ … There’s only one thing that is going to protect you, and that’s being perceived as somebody who is really just there for the truth and is as objective as possible.” The pair stayed for three months, shuttling between Baghdad and Nasiriyah. At that time, they were the only Western journalists working in the area because the roads were so dangerous. Garen and Carleton filmed the guards hired to protect the Sumerian site of Umma as the recruits trained and bought guns at a local arms market. On July 30, Carleton headed back to the United States, leaving Garen to wrap up the project. On Friday, August 13, two days before he was to return to New York, Garen went back to the arms market with interpreter Amir Doushi to grab just one more minute of footage. “To get a story and really document it, you had to take risks,” Garen said. Friday the 13th was not a lucky day. He aroused the suspicion of one vendor and within minutes he and Doushi were bundled into a car. Their captors held them in a cramped enclosure made from date palms in a remote marsh. They were completely cut off, and the guards were changed every few hours so that they could not strike up a relationship. His biggest stroke of luck was being held with Doushi. “If my translator hadn’t been there, I don’t know what I would have done,” Garen said. Doushi was able to gather snippets of information from the guards, and the two men kept each other company. The guards treated Garen relatively well, but they were harsh on Doushi for working for Americans. “We used all of our resources to convey that there’s no benefit in holding an innocent civilian like Micah hostage,” said Joel Campagna, CPJ’s senior program coordinator for the Middle East. The campaign seemed to be making headway, Carleton recalled, until the “terrible, terrible moment,” when the kidnappers’ video of Garen was broadcast. By this time, Garen believed death was imminent, and he began to devise an escape plan for the morning of August 19. At the last minute, however, Doushi backed out, arguing that an escape was too dangerous. He insisted that their chances of survival were greater if they stayed put. Despite the video, the families continued to make both private and public appeals to al-Sadr and local Muslim clerics. Garen’s sister, Eva, went on Arabic-language Al-Jazeera radio and Al-Arabiya television to plead for his freedom. Finally, al-Sadr, by now in hiding, wrote a letter demanding Garen’s release. On August 22, Garen and Doushi walked free. Garen said he bears no grudges about his ordeal. “Iraq is a place where you try not to have judgments. Our job being out there was to document,” he said. “In the greater scheme of things … you walk out alive, and it’s something to be happy about.” He set to work writing a book with Carleton about the ordeal, a process he says has been “cathartic.” The book is dedicated to their two sisters and the journalistic community. “That coming together was extraordinary,” Garen said. “I never thought that hundreds of journalists would be out there doing this.” Garen and Carleton want to return to Iraq, although they believe it is even more dangerous today. More than 50 journalists have been killed in Iraq since hostilities began in March 2003. The status of journalists, which Garen called his best protection, has been eroded by the violence. “Most journalists are either embedded or confined to their hotels,” said Garen. “Sadly, that barrier has kind of been crossed. … It no longer matters that you are a journalist.” American Hostage, by Micah Garen and Marie-Hélène Carleton, published by Simon & Schuster, October 2005. Maya Taal is CPJ’s executive assistant and board liaison. |

Despite the blindfold, Micah Garen caught a glimpse of what he feared would be the site of his execution. A large white banner with Arabic writing hung from a back wall. A dozen young men with weapons stood around the room. In the center was a video camera.

Despite the blindfold, Micah Garen caught a glimpse of what he feared would be the site of his execution. A large white banner with Arabic writing hung from a back wall. A dozen young men with weapons stood around the room. In the center was a video camera. But during his absence the mood in Iraq had soured. “Within a few months it changed dramatically, and then you realized your nationality was a target,” he said. Carleton, who has French and U.S. citizenship, traveled in full Islamic dress and the pair carried only her French passport, leaving their U.S. passports in their hotel room. They took painstaking precautions to keep their movements secret. They would hire two drivers the night before a trip then cancel one on the morning of their departure, not revealing their destination to the other until they were in the car. The couple thought that their best protection was their status as independent journalists, separate from any government or military.

But during his absence the mood in Iraq had soured. “Within a few months it changed dramatically, and then you realized your nationality was a target,” he said. Carleton, who has French and U.S. citizenship, traveled in full Islamic dress and the pair carried only her French passport, leaving their U.S. passports in their hotel room. They took painstaking precautions to keep their movements secret. They would hire two drivers the night before a trip then cancel one on the morning of their departure, not revealing their destination to the other until they were in the car. The couple thought that their best protection was their status as independent journalists, separate from any government or military. In New York, Carleton transformed the couple’s West Village apartment into a “war room” in a campaign to free Garen. “In the end it was the grassroots effort that would really pay off,” Carleton said. The leadership of the cleric’s Mehdi army had collapsed, and al-Sadr’s control over the splinter groups was tenuous. But a direct appeal to al-Sadr remained the best hope. Al-Sadr’s groups were open to journalists, Carleton said, but they had to be convinced that you were willing to report their side of the story. She galvanized journalists through emails and phone calls to use whatever contacts they had with al-Sadr’s people. She also worked with the U.S. government, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and other groups to get the message to influential Iraqis that Garen was an independent journalist covering a cultural story.

In New York, Carleton transformed the couple’s West Village apartment into a “war room” in a campaign to free Garen. “In the end it was the grassroots effort that would really pay off,” Carleton said. The leadership of the cleric’s Mehdi army had collapsed, and al-Sadr’s control over the splinter groups was tenuous. But a direct appeal to al-Sadr remained the best hope. Al-Sadr’s groups were open to journalists, Carleton said, but they had to be convinced that you were willing to report their side of the story. She galvanized journalists through emails and phone calls to use whatever contacts they had with al-Sadr’s people. She also worked with the U.S. government, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and other groups to get the message to influential Iraqis that Garen was an independent journalist covering a cultural story.