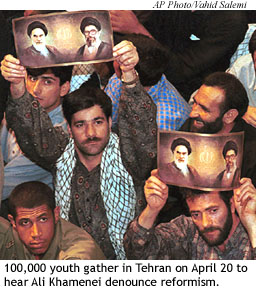

New York, May 5, 2000 —When Iran’s top cleric, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, launched a scathing tirade against the country’s pro-reform newspapers on April 20, journalists braced for the inevitable showdown. On previous occasions when the supreme leader had excoriated the press, the conservative-dominated judiciary responded with remarkable swiftness, shutting down newspapers and hauling journalists to court for running afoul of the country’s tough press law. But few journalists could have expected the magnitude of what was to follow.

Speaking before a congregation of 100,000 at Tehran’s Grand Mosque on April 20, Khamenei virtually accused the reformist press of being foreign agents. “There are 10 to 15 papers writing as if they are directed from one center, undermining Islamic and revolutionary principles, insulting constitutional bodies and creating tension and discord in society,” said Khamenei in his speech. “Unfortunately, the same enemy who wants to overthrow the [regime] has found a base in the country,” he added. “Some of the press have become the base of the enemy.”

Beginning two days later, the judiciary initiated a crackdown that resulted in the indefinite closure of 16 newspapers and magazines that had formed the core of the country’s burgeoning reformist press corps and were the collective backbone of support for President Muhammad Khatami and his agenda of social and political liberalization. The shutdowns suggested that the bitter power struggle between Iran’s entrenched conservative establishment and President Khatami had entered a critical new stage.

The sweeping newspaper closures, coupled with a dizzying spate of court summonses and jailings of Iranian journalists in recent weeks, signaled a major counter-offensive by hard-line elements following their defeat in February’s parliamentary elections. They saw that criticism in the reformist press was beginning to erode their authority. The crackdown sent a clear signal that conservative forces would not hesitate to use their control of key state institutions such as the judiciary to counterattack. In their view, the most effective way to block reform was to silence all critical voices. With second round runoff elections slated for today, May 5, they may have succeeded.

Writing revolution

While court-ordered newspaper closures and the detention of journalists have been common features of the larger drama being played out among Iran’s competing political factions in recent years, April’s judicial strike against the main reformist papers was unprecedented in its scope. Today, Tehran’s news kiosks are rather bare, and a somber mood of uncertainty seems to have settled in among journalists.

The atmosphere is striking compared with the optimism many reformist journalists felt after the election of President Muhammad Khatami in May 1997. Soon after taking office, Khatami delivered on his campaign promise to promote press freedom. In the ensuing months, dozens of new publications hit the market with the help of Khatami’s appointees in the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, which is responsible for licensing newspapers. These new media began to tackle political and social topics that would have been unthinkable just months earlier.

Before Khatami’s presidency, Iran’s press was a fairly monolithic body, tightly controlled by the state and trapped within the strict ideological limits of the Islamic revolution. Self-censorship, ideological loyalty, and tight government control over the licensing of newspapers contributed to the dearth of alternative publications. Though a few liberal intellectual publications existed, liberal writers had few platforms on which to express their ideas. And in general, political journalism was pitched at a rather abstract level, to avoid undue attention from government censors. “Ordinary people read [the moderate daily] Hamshahri for its ads or [the conservative daily] Kayhan for its Births and Deaths section,” said one observer in Tehran. “The liberal religious intellectuals read Kian magazine or Iran-e-Farda. Magazines had more room for intellectual and theoretical discussions. Current issues were hardly discussed.”

Before Khatami’s presidency, Iran’s press was a fairly monolithic body, tightly controlled by the state and trapped within the strict ideological limits of the Islamic revolution. Self-censorship, ideological loyalty, and tight government control over the licensing of newspapers contributed to the dearth of alternative publications. Though a few liberal intellectual publications existed, liberal writers had few platforms on which to express their ideas. And in general, political journalism was pitched at a rather abstract level, to avoid undue attention from government censors. “Ordinary people read [the moderate daily] Hamshahri for its ads or [the conservative daily] Kayhan for its Births and Deaths section,” said one observer in Tehran. “The liberal religious intellectuals read Kian magazine or Iran-e-Farda. Magazines had more room for intellectual and theoretical discussions. Current issues were hardly discussed.”

But with the explosion of new newspapers and magazines after Khatami’s election, the liberal press quickly assumed the role of government watchdog and political platform for the reform movement. Scrutiny of government corruption and other official misdeeds has become regular media fare. The press has also become the forum for a rich debate about the Islamic Republic’s theocratic form of government, including aspects of Islamic law regarding the death penalty and women’s rights. Liberal clerics even dared to publish articles criticizing the sacred political doctrine of velayat-i-faqih, or rule by the supreme religious scholar (i.e. Khamenei), and questioning whether the supreme leader should in fact be exempt from public criticism. Other journalists, meanwhile, have questioned Iran’s policy of unbending hostility towards the United States.

For their part, conservative papers poured out their aggressions against the pro-reform press, which is home to a diverse assortment of former high-level government functionaries, liberal clerics, and secular intellectuals, along with long-time professional journalists. “Much of the profound discourse within Iran today is taking place in Iran’s newspapers, courtrooms and classrooms,” Robin Wright, an American observer of Iranian political life, wrote earlier this year. “Even clerics who once held high office and intellectuals who were [Ayatollah Ruhollah] Khomeini protegés are now challenging the religion’s basic precepts as well as the specifics of theocratic rule.”

Reform Iranian style

The reformists are not pro-Western revolutionaries seeking to overthrow the current theocratic system. Rather, they represent the evolution of Iran’s Islamic revolution, aiming for more democracy, more respect for the rule of law, and more public freedoms within a broadly Islamist framework. “Iranian journalists and intellectuals do not oppose religious values, and the reformists do not want radical change in society,” said Ali Hikmat, editor of the now-defunct daily Fat’h, in a recent interview with the London-based Arabic daily Al-Hayat. “We are reformists who deem the constitution to be the ceiling. The freedoms allowed within the framework of the constitution are the maximum being sought.”

The reformists are not pro-Western revolutionaries seeking to overthrow the current theocratic system. Rather, they represent the evolution of Iran’s Islamic revolution, aiming for more democracy, more respect for the rule of law, and more public freedoms within a broadly Islamist framework. “Iranian journalists and intellectuals do not oppose religious values, and the reformists do not want radical change in society,” said Ali Hikmat, editor of the now-defunct daily Fat’h, in a recent interview with the London-based Arabic daily Al-Hayat. “We are reformists who deem the constitution to be the ceiling. The freedoms allowed within the framework of the constitution are the maximum being sought.”

By injecting new ideas and discourse into the public sphere, the reformist press has galvanized public interest in the political process, many Iranian commentators say. “One needs a whole day to read the newspapers these days,” one Tehran resident noted in early March. “There are so many of them and they are very diverse. A columnist writes a commentary about a certain issue, another writer replies to that commentary the following day in another paper. A third paper may later comment on either of them. You cannot miss one issue, otherwise you will be left in the dark.”

The press also filled the void created by the absence of official political parties, providing a forum for political debate.

For Iran’s emerging independent press, the April clampdown was the culmination of a relentless judicial campaign of harassment and censorship over the last two years. Newspaper closures by the infamous Press Court, charged with prosecuting alleged crimes committed in the press and headed by the notorious conservative judge Said Mortazavi, arrests and prosecutions of journalists, and long-term imprisonment have been the recurring themes in the battle for ideological hegemony.

Perhaps no incident better spotlighted the beleaguered state of the pro-reform press than last July’s court-ordered closure of the popular pro-Khatami daily Salam. The Special Court for Clergy closed down the paper on July 7, shortly after the Majles, the Iranian Parliament, passed a harsh draft press law. These two events triggered student demonstrations of a magnitude not seen since the 1979 revolution. Such setbacks, however, were generally taken in stride by journalists and viewed as the inevitable price to be paid for testing the boundaries of expression.

Despite repeated state efforts to silence the press through closures, reformist papers have proved adept at outmaneuvering the courts by launching new titles with the help of spare licenses handed out by sympathetic officials at the Ministry of Culture and Guidance. “Each time, I manage to publish a little longer, get a little bigger,” said leading publisher Hamed Reza Jalaiapour in an interview with Brill’s Content. “[My newspaper] Asr-e-Azadegan is up to 150 issues and counting … Of course if they close me down again, I’ve got another [newspaper] license. I can always get more.”

Crackdown 2000

But the situation began to change in February, after reformist candidates won an overwhelming majority of seats in elections held that month. The results gave Khatami an apparently strong mandate for his program to expand civil liberties and democratize Iran’s 21-year-old theocracy. The outcome also showed the increasing influence of the country’s vocal reformist press, which was unbridled in its criticism of candidates that it perceived as undesirable. Former president Hashemi Rafsanjani, for example, was the target of a number of stinging articles that accused his administration of corruption and implicated Rafsanjani himself in a string of mysterious political murders over the years. The coverage contributed mightily to Rafsanjani’s humiliating showing in the poll.

In the runup to the vote, these newspapers also helped mobilize public support for the reformist platform and helped voters identify pro-reform candidates. “By publishing a list of independent candidates, Tehran’s reformist newspapers helped the reformist parties,” according to an article in the leading pro-reform daily Asr-e-Azadegan, which became a casualty of the April press clampdown.

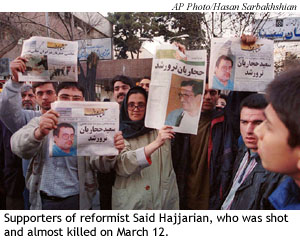

After the election things began to change quickly, and dramatically. On March 12, three weeks after the resounding reformist victory, Sobh-e-Emrooz publisher and influential Khatami advisor Said Hajjarian was shot in the face outside the offices of the Tehran city council . Critically wounded in the attack, Hajjarian is slowly recovering with a bullet still lodged in his spine. The alleged attacker went on trial on April 25 , along with seven other alleged co-conspirators, but Hajjarian’s reformist colleagues, many of whom believe that hard-line elements within the regime ordered the hit, are doubtful that the real truth will emerge.

The attack on Hajjarrian sent shock waves through the reformist press corps. Hajjarian was one of the main architects of the reformist victory in February, and his popular daily had taken the lead in an investigative inquiry into a string of mysterious murders of Iranian intellectuals and dissidents over the years, for which the paper blamed a shadowy group of hard-liners within the Ministry of Intelligence.

In the ensuing weeks, the conservative-dominated courts intensified their pressure, summoning scores of journalists to the Press Court and jailing others. On April 10, prominent reformist editor Mashallah Shamsolvaezin was convicted on appeal and sentenced to thirty months in prison for allegedly insulting Islamic principles in a 1999 article that criticized capital punishment in Iran. The article had appeared in the popular daily Neshat, which was shut down by the courts in September 1999.

On April 22, the popular investigative reporter Akbar Ganji, whose coverage of the political murders in Sobh-e-Emrooz had made him a celebrity, was arrested for violating the press law. And one day later, Shamsolvaezin’s former Neshat colleague Latif Safari was jailed after an appeal court upheld a 30-month jail sentence against him for a number of offenses including “insulting the sanctity and tenets of Islam”–the latter a reference to the same article on capital punishment that landed Shamsolvaezin in prison.

As the judicial machinery ground away, the outgoing, conservative-dominated Majles approved a series of new amendments to the press law that gave authorities even more powers to muzzle the press. One amendment bans individuals who belong to illegal groups, or who are deemed to have undermined Iran’s Islamic system of government, from practicing journalism–a provision that could give the courts considerable latitude to ban outspoken journalists from practicing their profession.

In the past, banned newspapers have been quick to re-launch under new titles. But a new amendment to the press law makes it more difficult for the publishers of banned newspapers to re-start their publications under new names. The law still awaits final approval by the Council of Guardians, but meanwhile pro-reform publishers seem to have adopted a wait-and-see attitude. In an April editorial, the reformist daily Asr-e-Azadegan declared, “The conservatives who dominate the Fifth Majles are determined to take advantage of the limited time left until the new Majles, which will be dominated by reformists, to punish one of the most serious factors in their electoral defeat. This factor was none other than the press.”

Concurrent with the judicial crackdown were a series of hostile public attacks from conservative institutions. On April 16, just four days before Ayatollah Khamenei unleashed his bitter attack against the press, the Revolutionary Guards–an elite military unit under the Supreme Leader’s control–issued a widely-reported statement warning pro-reform politicians and journalists that “when the time comes, small and big enemies will feel the revolutionary hammer on their skulls.”

Increasing the country’s already heightened political tensions are rumors of a pending coup against Khatami by the Revolutionary Guards (the Guards dismissed the rumors in a recent public statement). In the wake of the newspaper closures, reformists fear that conservative forces will try to block the new parliament from taking office. This could paralyze Khatami politically, by breaking his movement’s main channel to public opinion and blocking him from carrying out legal reforms.

The banned reformist newspapers have given no indication that they will attempt to re-open under new titles as was the case in the past. Their strategy for now seems to avoid direct confrontation with the conservatives and the potential crippling of their movement.

The conservatives, so far at least, have been successful in silencing the political debate that was being carried out in the press. Because of the crackdown, the reformist camp has enjoyed little media support prior to important parliamentary run-off elections scheduled for May 5. In the absence of reformist voices, conservative media have dominated coverage by default.

But it may already be too late. The reformist press has left an indelible imprint on Iranian society, and emboldened a youthful population hungry for change. “The hard-liners are desperate. They want to cling to power even if it means pushing the country toward a crisis,” one student protestor told the Associated Press. “But no matter what the hard-liners do, reforms are irrevocable.”

Joel Campagna is the Program Coordinator for the Middle East and North Africa at CPJ.>