Paulos Kidane was a poet, actor, and sports reporter. Political turmoil consumed his career and ultimately took his life. By Mohamed Keita

Paulos Kidane was not a political man–his passions were sports and poetry–but he became caught up in the destructive political whirlwind consuming Eritrea and Ethiopia in the late 1990s. Uprooted from his home, forced into state media service, thrown into prison for no reason other than sheer intimidation–the story of Paulos Kidane reflects the agony of the free press in this volatile region in the Horn of Africa.

After years of suppression, Kidane sought to break free from the politics that had overtaken his life. He wanted simply to cover the games he loved and to compose verse rather than propaganda. In July, in the searing, unforgiving landscape of northwestern Eritrea, he died seeking that end.

To write his story, CPJ interviewed 10 people in the Eritrean diaspora, many of whom would speak only on condition of anonymity because their families remain vulnerable to government reprisals. CPJ also reviewed a dozen personal notes that Kidane was able to send out of the country.

Kidane began his career in the mid-1990s as a freelance sportswriter in his native Ethiopia. At the outbreak of the border war with Eritrea in May 1998, Kidane was among more than 65,000 people of Eritrean descent who were deported.

Kidane began his career in the mid-1990s as a freelance sportswriter in his native Ethiopia. At the outbreak of the border war with Eritrea in May 1998, Kidane was among more than 65,000 people of Eritrean descent who were deported.

Kidane landed abruptly in the Eritrean capital, Asmara, a foreigner in his own motherland. “He had difficulties with [the local] Tigrinya language, especially writing, so I told him he could write in Amharic,” according to Khaled Abdu, co-founder and former chief editor of the now-defunct independent weekly Admas. Abdu hired Kidane as the paper’s sports editor after meeting him in the summer of 1999.

Kidane’s sports section focused on European soccer leagues and World Cup news. His favorite team was the prestigious Spanish club Real Madrid, Abdu recalled.

With the conflict raging, Admas, like most of Eritrea’s private press, adopted a supportive stance in its coverage of the government’s war effort. “There was no room for criticism,” Abdu said. When Admas published dissenting opinions, arrests and government threats ensued, forcing Abdu himself into exile in 2000.

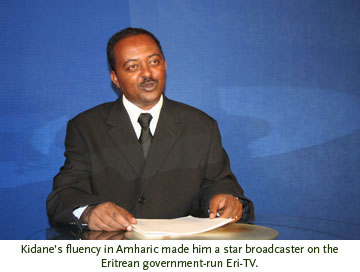

In May of that year, authorities recognized Kidane’s skill in Amharic and knowledge of Ethiopia, conscripting him into service as a presenter for the fledgling Amharic-language service of state broadcasters Eri-TV and Radio Dimtsi Hafash (Voice of the Broad Masses). The service was designed to broadcast anti-Ethiopian propaganda, giving prominence to the views of Ethiopian dissidents. As a Ministry of Information staffer, Kidane also covered European league soccer games on youth-oriented Radio Zara FM and Canal 2 television, according to former colleagues.

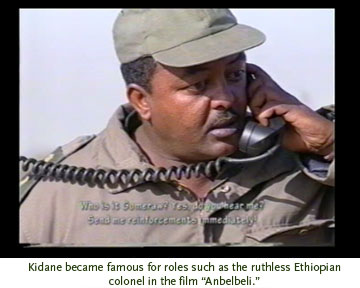

In a strange twist, Kidane’s fluency in Amharic vaulted him to fame as a film and stage actor. Kidane was given roles as villainous Ethiopian military officers in state-produced films and stage dramas recounting Eritrea’s 30-year armed resistance against Ethiopian occupiers. The country was still feting its Tegadelti–the veteran fighters of the ruling Eritrean People’s Liberation Front known by their khaki uniforms and black sandals.

In one film, “Anbelbeli,” Kidane donned the olive fatigues of a ruthless Ethiopian colonel who executes villagers and orders the shelling of enemy positions, only to be killed when the Tegadelti valiantly overrun his military outpost. During annual Independence Day celebrations, hundreds of people filled Asmara’s Liberation Avenue to watch Kidane perform similar roles in street theater dramas.

In one film, “Anbelbeli,” Kidane donned the olive fatigues of a ruthless Ethiopian colonel who executes villagers and orders the shelling of enemy positions, only to be killed when the Tegadelti valiantly overrun his military outpost. During annual Independence Day celebrations, hundreds of people filled Asmara’s Liberation Avenue to watch Kidane perform similar roles in street theater dramas.

For a time, his forced national service helped shield him from the worst abuses of the government’s crackdown on the press.

On September 18, 2001, just a week after the terrorist attacks against the United States, a split between reformers and conservatives within the ruling elite erupted into the summary ban of the private press and the arrests of more than a dozen independent journalists. A close friend of Kidane, Admas editor Said Abdelkader, was among at least 15 journalists thrown into prison without charge or trial for their critical coverage of the increasingly authoritarian regime of revered rebel leader Isaias Afewerki. Abdelkader and the others have not been seen since shortly after their detentions.

Kidane himself was detained for a week at a military camp in Sawa in January 2006 during one of the government’s frequent roundups of journalists and other citizens, according to a colleague and fellow detainee. The reason was unclear. “Nothing happened. We were there playing cards among ourselves for several days,” the colleague added.

Throughout 2006, in the face of such bullying tactics, several journalists in the Eritrean state media fled the country, some by foot, according to CPJ research. In November, in a move to intimidate others and prevent then from following suit, authorities arrested Kidane and at least eight other state journalists. Kidane was interrogated about his e-mail correspondence, according to one source, and several prisoners were allegedly beaten.

All of the journalists were released without charge after several weeks, but Kidane was hospitalized for respiratory problems he developed while in detention, according to the same source. Authorities forbade him from leaving Asmara.

The detention seemed to push a long-anguished Kidane into action.

The culture of the Ministry of Information, where staffers were encouraged to spy on one another, had tormented Kidane. According to a former colleague, “You had to be careful, even with the tone of certain jokes reflecting poorly on the government.” In expressing his frustration, Kidane once wrote, “For me it is tough because I am a sensitive man.” Kidane, who loved to write poems, was reduced to writing nationalist and anti-Ethiopian items, “proverbs, amazing news, facts, records, etc.” in the state-run daily Haddas Erta, according to one of his personal notes obtained by CPJ.

Born in Ethiopia, Kidane never felt comfortable in Eritrea either. “He was visibly frustrated,” Abdu said. “He told me he had lived in Ethiopia all his life.” Kidane was also struggling to support his wife and infant daughter, according to a friend.

In June, he set off on foot for Sudan in hopes of starting a new life.

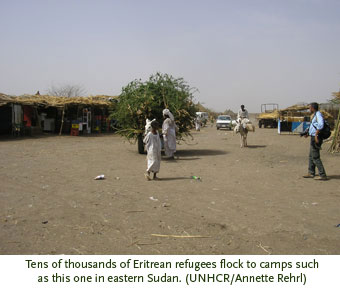

There are approximately 130,000 Eritrean refugees in eastern Sudan, with about 120 asylum seekers arriving each week, according to Annette Rehrl, a spokeswoman for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Sudan.

There are approximately 130,000 Eritrean refugees in eastern Sudan, with about 120 asylum seekers arriving each week, according to Annette Rehrl, a spokeswoman for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Sudan.

At least 19 journalists have fled Eritrea since 2002 in response to threats, harassment, and imprisonment–the third highest number worldwide, according to CPJ research. The government’s absolute monopoly on domestic media, the fear of reprisal among prisoners’ families, and tight restrictions on the movement of all foreigners led CPJ in 2006 to name Eritrea one of the 10 most censored countries in the world.

Many refugees flee from years of compelled national service, while others leave after the arrest or disappearance of a relative, according to Rehrl. Eritrea’s compulsory national service conscripts the able-bodied population to military, agricultural, construction, or civil service duties that is often extended for many years.

Eritrea, home to 4.9 million, conscripts the highest proportion of citizens in the world into military service, forming sub-Saharan Africa’s largest army, according to U.N. figures. After fighting two bloody wars against its neighbor and arch foe Ethiopia, the Red Sea nation is on a seemingly permanent war footing.

Authorities frequently order military roundups of citizens, including civil servants such as Kidane, in response to perceived threats of Ethiopian aggression. The Ministry of Information itself has artillery weapons to repel an Ethiopian attack. Overlooking Asmara across a fortified hill named Forto, the modern complex occupies the former site of Italy’s main colonial military base.

International inquiries about jailed journalists, particularly those imprisoned in the 2001 crackdown, have been ignored or met with hostility. “This is an Eritrean issue; leave it to us,” Information Minister Ali Abdu told CPJ in June when he was asked to confirm the death in prison of Fesshaye “Joshua” Yohannes, the award-winning editor of the now-defunct independent newspaper Setit.

But seven days of walking–surviving on dry rations, water, and powdered milk–was too much for Kidane, the only journalist and the senior member of the group. An epileptic, he collapsed in a violent seizure and temporarily blacked out. Shaken, badly needing rest, and pained by blisters on his feet, Kidane begged his companions to continue without him, the woman said, breaking into tears. The journalist had to be left in the care of residents in a nearby village teeming with government informants.

It was the last time Kidane was seen alive. He was 40.

Kidane’s condition was not critical when the group left him, the woman insisted, saying that even in the event of complications, he would have survived had he received proper medical care. She believes Kidane may have been captured by government security forces.

More than a month after reports of his death circulated on Eritrean diaspora Web sites, officials would not publicly confirm that Kidane had died. In a telephone interview with CPJ in August, Abdu, the information minister, finally acknowledged that the journalist perished while attempting to leave the country, but he offered no information about the circumstances. “We don’t know,” he said.

What is known is this: The Eritrean government is responsible for creating the stifling and exploitative conditions that led Paulos Kidane to flee. He wanted to pursue his passions. Instead, his career and his very life were taken from him.

Mohamed Keita is the research associate for CPJ’s Africa program.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This report has been updated to reflect the correct name of the state daily Haddas Erta.