By Abi Wright

Four years after Daniel Pearl was brutally murdered in Pakistan, questions and concerns remain.

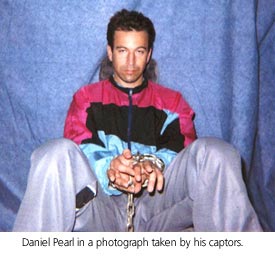

| In the evening of January 11, 2002, Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl walked into a hotel near the Pakistani capital, Islamabad, and was introduced to a man who called himself Bashir. Pearl thought he was meeting a potential source who could help him get access to a radical Islamic cleric for a story on terrorism. In fact, that night Pearl met a British-born Pakistani militant with a track record of kidnapping Westerners. His real name was Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh. Instead of helping Pearl land a scoop, the meeting with Saeed set events in motion that led to his entrapment, kidnapping, and murder, U.S. officials say, at the hands of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the suspected mastermind behind the 9/11 attacks on the United States.

Pearl traveled to Pakistan at a particularly tense time, according to Bruce Hoffman, a terrorism expert at the Rand Corp. in Washington. With the fall of the Taliban regime in neighboring Afghanistan in December 2001, militants were pushed out. “When they lost their geographical center of gravity in Afghanistan, they went to Pakistan, which was something of a haven because they had longstanding relations with existing (militant Islamist) groups.” On January 23, 2002, after exchanging e-mails with Saeed for nine days, Pearl was lured to a restaurant in the southern port city of Karachi. He got into a car he thought would take him to interview a reclusive Islamic leader. Instead, he was kidnapped and held for a week before being killed. A video camera recorded the grisly act. The search for Pearl continued for several weeks until a copy of the video surfaced on February 21, 2002. Pearl had been researching a radical Islamic leader, Sheikh Mubarik Ali Gilani, who had been linked to the so-called “shoe bomber” Richard Reid. Reid tried to blow up an American Airlines flight from Paris to Miami in December 2001. To find his way to Gilani, Pearl did what reporters do every day–he reached out to new contacts and made himself accessible. That also made him a target, Hoffman said. “It is a question of opportunism and access. A reporter has to chase a story, making him or her more vulnerable.” Journalists investigating militant groups and their connections to terrorist activities were not welcome, according to Pearl’s widow, Mariane, who traveled with him to Karachi and who wrote about her experience in her 2003 book, A Mighty Heart. A pattern of overlapping Islamic militant groups with ties to al-Qaeda emerges from the arrests in the Pearl case. Three separate groups carried out the crime: the organizers of the kidnapping who lured Pearl; those who detained him; and those who carried out the execution. Saeed turned himself in to police on February 12, 2002, but he told a court in Karachi that he had first surrendered to the ISI one week earlier in Lahore. What took place during his time with the ISI is not known, but Saeed’s association with the powerful intelligence agency appears to be protecting him, Pearl’s family said. “He is kind of untouchable,” Mariane Pearl told CPJ. Saeed was a member of the militant Islamic group Jaish-e-Mohammed whose goal is to unite Indian-administered Kashmir with Pakistan. He told police that he plotted to seize Pearl because he wanted to strike at the United States and embarrass Pakistani President Gen. Pervez Musharraf on the eve of his visit to Washington, The Journal reported. Fazal Karim, a militant belonging to Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, a Sunni Muslim group with ties to the Taliban, provided more information. He confessed to his involvement in May 2002 when he was arrested in connection with a bomb attack on Karachi’s Sheraton Hotel. He says he witnessed Pearl’s execution by three Arabic-speaking men who showed up without warning. Hashim Qadeer, a member of the Kashmiri separatist group Harkat ul-Mujahideen, who first introduced Pearl to Saeed, was detained in July 2005. At least two others connected with Pearl’s murder remain at large: Saud Memon, who owned the property where Pearl was held and killed; and at least one man who was present when Pearl was murdered, according to The Journal. Despite the arrests, appeals have brought the case to a near standstill. A court convicted Saeed and three others of the kidnapping and, in July 2002, sentenced Saeed to death by hanging. “He was sentenced to death very quickly, but it was also obvious that it was a political trial. He knew that he was protected. He even said at the time ‘The people who put me here will die before I do,'” Mariane Pearl said. From behind bars, Saeed continues to make public statements. He gave an interview to Britain’s Sunday Telegraph in which he pledged allegiance to Taliban leader Mullah Omar and said, “I’m trying to prepare myself to be of real service to the ‘ummah’ (Muslim nation) if I get another chance.” The three others convicted in the kidnapping–Fahad Naseem, Salman Saqib, and Sheikh Mohammed Adeel–received 25-year jail sentences. All are appealing and the process has been subject to delaying strategies by lawyers. In July 2004, The Journal reported on one tactic: “Mr. Saeed’s lawyer, Abdul Waheed Katpar, requested adjournments at least twice last year on the grounds that his client’s father had borrowed the case file on Mr. Saeed and hadn’t yet returned it.” The appeals have been delayed more than 30 times and show no signs of moving forward, Pearl’s father, Judea Pearl, told CPJ. “Obviously the court allows them to play the game of delay for some reason. It is obviously also conducted from the top in the sense that the regime is not interested in executing the sentence.” Mariane Pearl sees the hand of the intelligence services behind it. “Pakistan itself cannot carry out the sentence. That tells you about the power of the ISI,” she said. The delays have a domino effect on other parts of the prosecution. Four other men detained in the case cannot be formally arrested or charged until the first four cases are resolved because the men would be tried with the same evidence, according to former special prosecutor M.Z. Haq, who tried Saeed. If the first four sentences are overturned, it would have direct implications on the other four men’s cases, he noted. Yet by local standards, Haq said, Saeed’s case is unusual in its delays. “This is an extraordinary and exceptional case because normally, with a death sentence case, the verdict is carried out within six to nine months,” Haq said. “The process isn’t efficient,” said Bussey, who went to Karachi in 2002 when Pearl was kidnapped and who follows the ongoing cases. “When we regularly ask officials in Islamabad and Karachi why the appeal hasn’t been heard and the sentence finalized and executed, we’re told that the Pakistani judicial process requires patience.” For Pearl’s family, patience is running thin. “We are looking for closure,” Judea Pearl said. “We don’t know what happened that last few days and we have not received this information. We have been after (the U.S. State Department and the FBI) for four years to hear one scenario that will match all the clues, and we haven’t received it yet.” Reports in the British and Indian press that Saeed continues to receive visitors and communicate with followers from jail disturb the Pearls. Normally, those sentenced to death are allowed only short visits with family members and are not permitted to speak to the press, Haq said. “It hurts that he is still operating from prison,” Pearl’s mother, Ruth, said. Saeed has been linked to other crimes since he was arrested. After two assassination attempts on Musharraf, prison authorities moved Saeed from Hyderabad to Adiala prison near Islamabad in January 2004. He was questioned there about his connection to the man behind the plots, Amjad Hussain Farooqi, a militant with links to al-Qaeda. Farooqi, who also played a role in orchestrating Pearl’s kidnapping, died in a shoot-out with Pakistani security forces in September 2005. More pressure is needed to resolve the case, Mariane Pearl said. “There is a lack of will to pressure Pakistani authorities by the U.S. government and by The Wall Street Journal,” she said. Bussey responded that his newspaper hired a lawyer in Karachi to advise it on the case and has contacted all relevant parties. “The Journal has urged a swift resolution of the prosecution of this case with President Musharraf, with other Pakistani government officials in Islamabad and those visiting the U.S., and with the Bush administration,” he said. Three years ago, in June 2003, Musharraf told reporters that the Pearl case was “history.” Pearl’s parents responded in a letter to the editor of The Journal on July 8, 2003. They said their son’s case would remain an open wound until two conditions were met: “All those involved in the planning and execution of the murder are brought to justice and justice is served, and a monument to Daniel Pearl is erected in Karachi, reaffirming the ideals for which he stood: truth, humanity and dialogue.” Those steps remain Information on the Daniel Pearl Foundation is available at www.danielpearl foundation.org Abi Wright is CPJ’s communications director and former Asia program coordinator. |

Four years on, significant progress has been made in bringing Pearl’s killers to justice. “We believe that most, but not all, of the key figures in Danny’s kidnapping and murder have either been killed or are in jail,” said Wall Street Journal Deputy Managing Editor John Bussey. But questions linger about who ordered the murder and what precisely happened. Saeed, the mastermind of the kidnapping, is on death row but is delaying his appeals amid allegations that he is protected by Pakistan’s powerful Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI). He has also violated Pakistani prison rules for death row inmates by making contact with the outside world from his prison cell. It seems uncertain he will ever be executed, according to the Pearl family, who are frustrated by the slowness of the investigation and want Saeed’s sentence carried out.

Four years on, significant progress has been made in bringing Pearl’s killers to justice. “We believe that most, but not all, of the key figures in Danny’s kidnapping and murder have either been killed or are in jail,” said Wall Street Journal Deputy Managing Editor John Bussey. But questions linger about who ordered the murder and what precisely happened. Saeed, the mastermind of the kidnapping, is on death row but is delaying his appeals amid allegations that he is protected by Pakistan’s powerful Inter-Services Intelligence Agency (ISI). He has also violated Pakistani prison rules for death row inmates by making contact with the outside world from his prison cell. It seems uncertain he will ever be executed, according to the Pearl family, who are frustrated by the slowness of the investigation and want Saeed’s sentence carried out. Other arrests in the case include Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, al-Qaeda’s third-ranking operative, who was snared in March 2003 near Islamabad. U.S. officials say that he carried out Pearl’s execution. He is being held in U.S. custody at an undisclosed location. To extract information from Mohammed, CIA interrogators used a technique called “water-boarding,” where the suspect is held under water to the point of nearly drowning, The New York Times reported.

Other arrests in the case include Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, al-Qaeda’s third-ranking operative, who was snared in March 2003 near Islamabad. U.S. officials say that he carried out Pearl’s execution. He is being held in U.S. custody at an undisclosed location. To extract information from Mohammed, CIA interrogators used a technique called “water-boarding,” where the suspect is held under water to the point of nearly drowning, The New York Times reported.