Twitter’s permanent suspension of President Donald Trump’s account is reinvigorating debate about the law that protects social media platforms – specifically, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. The statute shields tech companies and news websites from liability for making decisions about what people can say on their platforms, whether they take it down, or leave it up.

The issue will not subside after Trump leaves office. While campaigning a year ago for his party’s nomination, President-elect Joe Biden, who will take over the White House on January 20, told The New York Times editorial board that “Section 230 should be revoked…for [Facebook] and other platforms” that were “propagating falsehoods they know to be false.”

While experts have widely divergent views about whether and how to reform Section 230, they say potential ramifications for journalists include a significant increase in content takedowns and hurdles to crowdsourcing – trends that would be likely to hurt independent journalists more than large outlets.

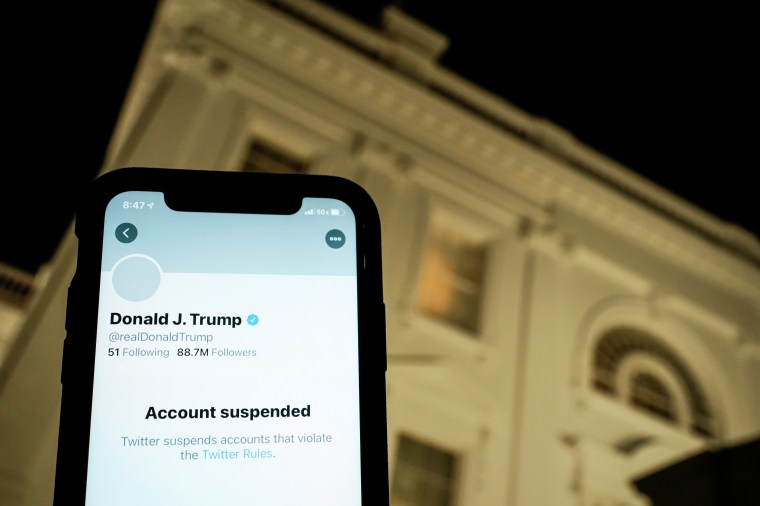

Twitter on January 8 cited the risk of further incitement to violence in the wake of the riot at the U.S. Capitol for its decision to suspend the @realDonaldTrump account, putting an end to the fraught relationship between the outgoing president and the platform. Last month, Trump vetoed a major piece of legislation on defense spending in a failed attempt to pressure Congress to address Section 230. Trump had intensified pressure to act after Twitter began applying fact-checking warnings to his posts, AP reported in May last year. A 2020 executive order he issued prompted additions to a growing pile of proposals to reform the statute, many of which would either promote fact-checking or restrict it, according to an analysis published in Slate.

Section 230, which holds that no provider of an “interactive computer service” shall be treated as the “publisher” or “speaker” of information provided by a third party, allows companies to moderate legal but unwanted content without fear of expensive lawsuits, including news websites who moderate online comments. The law’s advocates—among them, the Electronic Frontier Foundation and technology companies that offer cloud hosting, publishing, or other services that enable digital communication—argue that it supports the free exchange of information. Yet others believe that the threat of liability would incentivize dominant social media companies to crack down on online harassment and misinformation, issues that CPJ has found can have safety implications for the press.

Journalists and legal experts told CPJ they are yet to be convinced by existing legislative proposals. Though some support Section 230 reform in principle, all are wary of unintended consequences, especially if the statute is simply revoked. In interviews, they speculated that without Section 230, companies would need resources to manage liability, and strategies to reduce it—a change that would favor established players. Giants like Google, Facebook, and Twitter might lean more on known news brands to identify quality information, they said, but smaller operations might shut down interactions altogether. In other words, Section 230 reform could reduce misinformation or abuse—but it could also restrict citizen journalism.

Mary Anne Franks, a professor at the University of Miami School of Law and president of the anti-online abuse nonprofit the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative, supports reforming Section 230, she told CPJ, but “not to expect [platforms] to screen every piece of material or pre-emptively make judgments about what is true and what is not.” Instead, she is seeking a legal standard that allows the possibility of a lawsuit if, for example, “a plaintiff can say there was non-consensual pornography of me on your platform, or you published my home address, and you were alerted multiple times and took no action.”

The courts would still decide whether a suit had merit, she said—and many of the platforms’ decisions would still be protected by the First Amendment. Private actors like Facebook and Google don’t have First Amendment obligations to protect speech, including abuse of the kind many journalists report being exposed to online. Rather, “[platforms] themselves have First Amendment rights to not carry speech they disagree with.”

“To put it simplistically, there are two parts of Section 230, one being that you’re not responsible for the stuff you leave up,” Franks said, the other “that you are protected from anyone complaining that you took stuff down.” Franks, like other interviewees for this story, spoke to CPJ prior to the Capitol riot and Twitter’s move to suspend Trump.

But if Section 230 encourages content moderation, why is online abuse such a problem? “Because they’re not liable, you would think they would be vigilantly going after [content that violates] their terms of service, but they’re not,” Danielle Coffey, senior vice president and general counsel of the News Media Alliance, told CPJ of the dominant social media platforms. The Alliance, a nonprofit group representing professional media outlets, recently sent Biden’s team a policy recommendation to “work with Congress on a comprehensive revision” of Section 230 to remove legal immunity for platforms that “continuously amplify – and profit from – false and overtly dangerous content.”

For Franks, the existing incentives are misaligned. “The answer has to be reform [Section] 230 to make companies care in a way that’s not simply up to a particular CEO on a particular day.”

But she cautioned that revoking the statute would have side effects. “In the wake of something like a repeal you would see a lot of things getting taken down while companies try to reassess their risk levels,” Franks said, though she believes that impact would be short-lived once frivolous suits were kicked out of court.

Eric Goldman, a professor at Santa Clara University School of Law, has written extensively about Section 230 since it came onto the books in 1996. “I think it’s naïve to assume that increased liability on part of internet services will motivate them to do more to clean up their content,” he told CPJ. “The more likely outcome is that they will restrict who has access to their service overall. I think the future of Twitter is to look more like a playground for brands and celebrities.”

Might that serve the press? “People do ask me what’s the benefit to news publishers if the platforms are liable,” Coffey said. “That means that they have to carry more responsible content, and guess what, that’s us.” She pointed to projects like NewsGuard, a ratings tool to help readers and advertisers assess the trustworthiness of news content, as one example of how platforms might distinguish “quality from non-quality.”

But Goldman foresees other effects. “All the leads [that journalists] are currently accruing from people on the ground, those get cut off in a regime with greater liability.” And without Section 230, he said, “Comments sections for newspapers would easily go.”

He also cautioned that if the target of reform is misinformation, changing Section 230 might not have the desired effect. “Here in the U.S., there is defamation, and there are things that are mean or perhaps misleading but not otherwise actionable, but there’s no categorical prohibition against misinformation,” he said. “Is anyone liable for it? If not, changing Section 230 doesn’t change the answer.”

Other experts have sounded warnings about unintended consequences of poorly designed reform. In June, Hye Jung Han, who researches children’s rights and technology for Human Rights Watch, told the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee in a public letter that the EARN IT Act, one of the legislative proposals that would weaken Section 230 protections, would limit free expression online without introducing adequate measures to protect children, the bill’s purported aim. She and other digital rights groups like the Washington D.C.-based Center for Democracy and Technology flagged concerns that the bill would require companies to review private content, undermining privacy and potentially causing some to weaken encryption – which is essential for journalists to protect the confidentiality of their sources — in order to comply.

Getting it right matters, Han told CPJ in December. “If you’ve got specific legislation in the U.S. that determines how U.S. companies need to operate, they will tend to adopt those as the baseline standards for their global operations.”

Journalists who manage online comments face liability without Section 230

Mathew Ingram writes about media and technology for the Columbia Journalism Review, and manages conversations on Galley, the publication’s in-house forum for longform, interactive interviews, which he described to CPJ as“an attempt to reinvent the comments section” by restricting discussion to trusted participants.

Ingram has hosted several Galley discussions with journalists who have left employment to publish their own work. He emphasized the impact of a sudden legal change on blogs and self-funded citizen journalism. “Smaller places would probably shut down whatever comment features they had because the risk is too great without Section 230,” he told CPJ. “The irony is that YouTube and Facebook and Twitter are more than capable of handling [the risk], but anyone below that level could be bankrupted by a lawsuit.”

“Most of our papers are taking [comments] down already,” Danielle Coffey of the News Media Alliance said. CPJ—which disabled comment functionality on cpj.org in 2016—has noted before that several prominent outlets have done away with comments, and that moderating them carries an emotional burden.

That burden is real, and falls disproportionally on women and people of color, according to Andrew Losowsky, head of The Coral Project at Vox Media. Coral is a commenting platform developed out of a grant-funded collaboration with Mozilla, The Washington Post, and The New York Times, that is now used by nearly 200 news websites in 21 countries. “Definitely we need better ways of helping law enforcement understand what harassment means in the internet age,” he told CPJ. But for him, moderation is part of the solution.

“The problems with online communities right now are not technical problems,” he said in a video interview. “The problems are strategy and culture problems that technology can help and hinder.”

Coral’s guidelines advise media outlets to identify the purpose of having conversation first, then a productive way to encourage it in a specific community. That doesn’t mean an open forum at the bottom of every article, Losowsky told CPJ—contentious issues or obituaries, for example, do better without them, and journalists can vet comments for colleagues who are likely to face attack for the most constructive input. “It’s not open conversation everywhere or no conversation,” he said.

“It’s interesting that Twitter is experimenting with features that effectively duplicate the kind of thing that Galley was designed to do and restrict the discussion to certain people,” Ingram said. Twitter allowed people to limit who can reply to their tweets in August; hiding replies was enabled in 2019 to stop repliers from derailing conversation.

“If journalism continues on a path of saying, “We’re not going to listen to you, we don’t read the comments, we’re just going to talk at you,” then I really fear for the future of journalism,” Losowsky said. “Saying journalists do not want to do that anymore—and we would like the government to make it harder for us to do that—feels like a backward step.”

“If what you want is for people to commit random acts of journalism and post videos of the police beating people to death, and so on,” Ingram said, “you can’t structure a tool like Section 230 so that it only protects the good stuff. The same principles apply to non-journalists as to journalists, and that’s a good thing.”