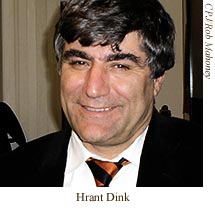

New York, January 19, 2007—The Committee to Protect Journalists condemns the murder today of a prominent Turkish-Armenian editor outside his newspaper’s offices in Istanbul. Hrant Dink, 52, managing editor of the bilingual Turkish-Armenian weekly Agos, was shot three times in the neck, according to the Turkish television channel NTV.

Dink had received numerous death threats from nationalist Turks who viewed his iconoclastic journalism, particularly on the mass killings of Armenians in the early 20th century, as an act of treachery. In a January 10 article in Agos, Dink said he had passed along a particularly threatening letter to Istanbul’s Sisli district prosecutor, but no action had been taken.

“Through his journalism Hrant Dink sought to shed light on Turkey’s troubled past and create a better future for Turks and Armenians. This earned him many enemies, but he vowed to continue writing despite receiving many threats,” said CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon. “An assassin has now silenced one of Turkey’s most courageous voices. We are profoundly shocked and saddened by this crime, and send our deepest condolences to Hrant Dink’s family, colleagues, and friends.”

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan condemned Dink’s death as an attack against Turkey’s unity and promised to catch those responsible, according to international news reports. Police identified the assailant as a young man dressed in a white hat and a denim jacket, and they detained two people as part of their investigation, NTV reported.

“This murder must not go unpunished as have previous slayings of journalists,” said CPJ’s Simon. “We call on the Turkish authorities to do all in their power to ensure that those responsible are brought to justice swiftly.”

In the last 15 years, 18 other Turkish journalists have been killed for their work, many of them murdered, making it the eighth deadliest country in the world for journalists, CPJ research shows. The last killing was in 1999. More recently, journalists, academics, and others have been subjected to pervasive legal harassment for statements that allegedly insult the Turkish identity, CPJ research shows.

Dink, a Turkish citizen of Armenian descent, had been prosecuted several times in recent years—for writing about the mass killings of Armenians by Turks at the beginning of the 20th century, for criticizing lines in the Turkish national anthem that he considered discriminatory, and even for commenting publicly on the cases against him. His office had also been the target of protests.

In July 2006, Turkey’s High Court of Appeals upheld a six-month suspended prison sentence against Dink for violating Article 301 of the penal code in a case sparked by complaints from nationalist activists. His prosecution stemmed from a series of articles in early 2004 dealing with the collective memory of the Armenian massacres of 1915-17 under the Ottoman Empire. Armenians call the killings the first genocide of the 20th century, a term that Turkey rejects.

Ironically, the pieces for which Dink was convicted had appealed to diaspora Armenians to let go of their anger against the Turks. The prosecution was sharply criticized by the European Union, which Turkey is seeking to join. Dink said he would take the case to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France, to clear his name.

Dink was one of dozens of writers who have been prosecuted in the past two years under controversial penal code provisions that criminalize statements deemed as insulting to the Turkish identity, particularly in regard to the Armenian killings, CPJ research shows. The local press freedom group Bia said at least 65 cases have been launched against journalists, writers and academics. The EU has urged Turkey to reform its laws to eliminate such prosecutions.

Dink edited Agos for all of the newspaper’s 11-year existence. Agos, the only Armenian newspaper in Turkey, had a circulation of just 6,000 but its political influence was vast. Dink regularly appeared on television to express his views.

In a February 2006 interview with CPJ, Dink said Turkish nationalists had targeted him for legal harassment. “The prosecutions are not a surprise for me. They want to teach me a lesson because I am Armenian. They try to keep me quiet.” Asked who “they” are, Dink replied, “the deep state in Turkey”.

He was referring not to the Islamist-based government of Prime Minister Erdogan, but to the secular nationalist forces supported by sections of the army, security forces, and parts of the justice and interior ministries. The nationalists, political heirs of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey, still exert considerable influence in Turkey.

Dink said in the CPJ interview that he hoped his critical reporting would pave the way for peace between the two peoples. “I want to write and ask how we can change this historical conflict into peace,” he said.

In the interview, Dink said he did not think the tide had yet turned in favor of critical writers—“the situation in Turkey is tense”—but he believed that it ultimately would. “I believe in democracy and press freedom. I am determined to pursue the struggle.”