Twitter announced last week that it would start labeling some accounts run by media outlets and their top editors as “state-affiliated,” a descriptor intended to improve transparency about the source of information being shared on the platform.

Since disinformation became a flash point in the debate over content moderation on social media, distinguishing propaganda from public service news has become a priority for companies that operate global platforms–especially when editorially independent outlets receive government funding. Facebook and Google, which owns YouTube, apply their own versions of Twitter’s label. Twitter has also said it will not accept advertising from state-controlled media, while Facebook blocks state media accounts from advertising to U.S. audiences, citing concerns about political information being manipulated ahead of elections in November. YouTube representatives have told CPJ the company uses the same label to identify state-funded outlets and their advertising.

The classification efforts appear timed to stave off government interference. When top Facebook and Google executives appeared before a congressional antitrust committee in July, they had to answer questions about how their platforms address disinformation. A UK Parliamentary inquiry has separately called for an independent regulator to impose a compulsory code of ethics on companies perceived to enable the spread of “fake news,” with the power to bring legal action against them for violations. As policymakers continue to probe the dominance of the social media platforms–and their role in facilitating the global spread of disinformation that influences decision-making about elections and other democratic institutions–companies may be hoping that self-regulation helps preempt such controls.

Labeling state media is fraught. In separate investigations, CPJ and ProPublica have found YouTube’s labeling to be inconsistent. Several observers and people working at outlets that have been subject to such designations say the process lacks transparency, according to CPJ interviews and public statements. Some said they perceive the labels as derogatory and subjective; others welcomed them, noting their potential to improve transparency for users regarding where information comes from. However, many agreed that categories with more nuance, applied to a wider array of media organizations, would make labels more effective.

Determining the level of state interference in a given media outlet requires considerable expertise, according to several journalists and experts. Many told CPJ they agree the platforms have a role in addressing propaganda which stokes disinformation. Yet neither they, nor the companies responsible for the policies, could point to evidence of the impact of labeling. It’s not clear that identifying such outlets on social media improves media literacy or reduces the reach of propaganda–or whether it changes the way readers engage with labeled content. In the meantime, however, the companies are adopting definitions with the potential to reduce the visibility of select media outlets, their ability to advertise, and how audiences encounter their work on social media.

“I think most of us are in favor of helping users understand where their news is coming from,” said Matthew Baise, the director of digital strategy for the U.S. Congress-funded broadcaster Voice of America (VOA), who oversees its social media accounts in 47 languages.

“I’m all in favor of labeling,” said Anya Schiffrin, a former journalist who directs technology, media, and communications studies at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. “If you don’t want regulation then you have to believe in consumer choice, and labeling is part of promoting consumer choice.”

Twitter’s August 6 announcement says the company will apply the policy to accounts run by news media that they determine are affiliated with the state, as well as their senior staff, starting with those from the so-called P5 countries—China, France, Russia, the U.K., and the U.S.—that hold permanent positions on the U.N. Security Council. State-financed media that enjoy editorial independence, like the BBC in the U.K. and U.S. National Public Radio (NPR), would not receive the label, the announcement said. Accounts run by government spokespeople, like foreign ministers and ambassadors, will also be labeled.

Labeled accounts and their content will no longer be amplified through the platform’s recommendation systems, Nick Pickles, Twitter’s public policy strategy director, told CPJ–meaning that readers may be less likely to see their posts.

Twitter selected the initial target countries because of their “outsized influence on the global conversation,” Pickles told CPJ. These states also fund and operate media outlets in scores of languages and jurisdictions, making them harder to assess. In 2019, CPJ documented an “information war” that social media platforms had identified involving accounts originating in mainland China, where the platforms are generally censored. The “significant state-backed information operation,” as Twitter described it, sought to discredit pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong. According to Pickles, journalists working for Chinese state media were running ads and tweeting about the protests without their affiliation being clearly visible in posts, including some that went viral.

Google, which began identifying “state-funded” outlets on YouTube in 2018, now labels content from both state and publicly-funded news outlets in 22 countries, primarily in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region. Facebook announced its policy in 2019 but delayed implementation, in part due to lobbying by resistant media outlets. After consulting with 65 experts and organizations, including CPJ, Facebook said in June this year that it would begin identifying media content and ads from outlets as “state-controlled” if they were “wholly or partially under the editorial control of their government,” excluding public service media.

“The purpose of the labels is to provide context on the video that people are viewing,” a Google official told CPJ in June. The aim was “not to dissuade people from viewing content, but to understand that the content they are viewing is coming from a government channel,” the official said, declining to be identified by name per company policy.

“There’s no such thing as a collectively agreed upon definition,” said Sarah Shirazyan, Facebook’s stakeholder engagement manager for content policy, who helped develop its rules. “One pattern that emerged was that funding was not the only way of influencing or controlling the media,” she said. “The policy recognizes that state media have an agenda setting power, an opinion making power, that is coupled with the strategic power of the state. But it also recognizes that state media are not always bad, so we don’t want to remove them from the platform.”

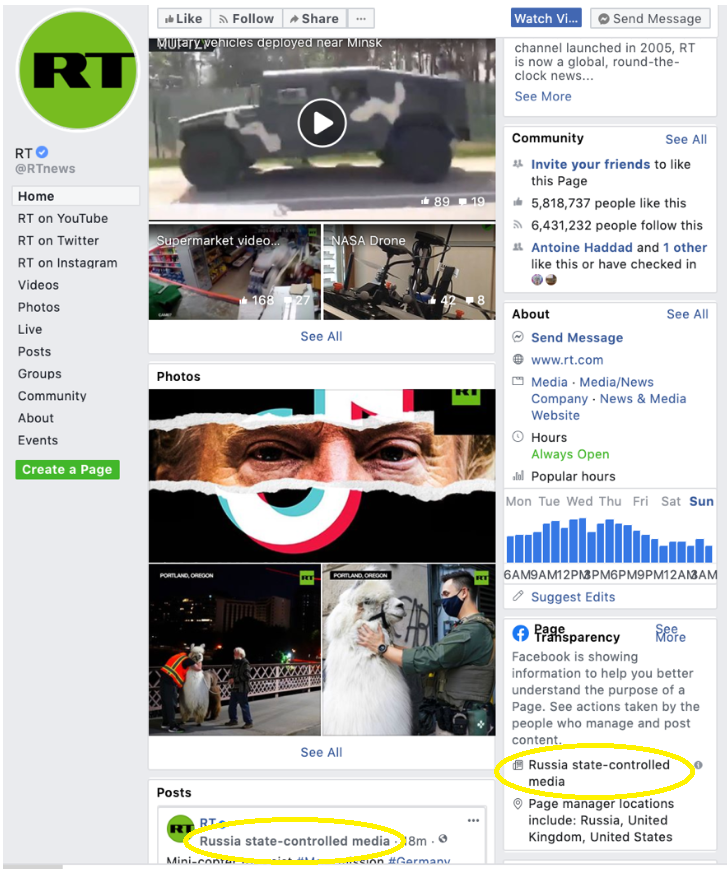

A screenshot of RT’s Facebook labels seen from Washington, D.C. (CPJ).

“Facebook asked a lot more questions and seemed to really be trying to wrestle with this question of state-controlled versus state-funded,” said VOA’s Baise.

Representatives of the Qatar-funded news network Al Jazeera, however, told CPJ they oppose Facebook’s terminology. Though accounts run by the broadcaster are not currently labeled on Facebook, they said this could change without warning.

“There’s a big difference between the YouTube label and the Facebook label,” said Andrew Koneschusky, a partner at DC-based public affairs firm CLS Strategies who advised Al Jazeera in its discussions with Facebook, noting that “state-funded” was a factual determination, while “state-controlled” is subjective. “Facebook controls so much of what we see and how we interpret the world and the content around us, so it is important from that perspective.”

“The reason we object so forcefully is because for us, perception is reality in the world in which we live,” said Michael Weaver, a business development executive in Al Jazeera’s digital division. “If we’re being undermined by other platforms, it spreads across not only what Al Jazeera is doing but it spreads across all these geopolitical conflicts that are happening in the area.” Since 2017, a Saudi-led quartet of governments have called on Qatar to shutter the broadcaster, among other demands. “It could be a death blow to the network,” Weaver said.

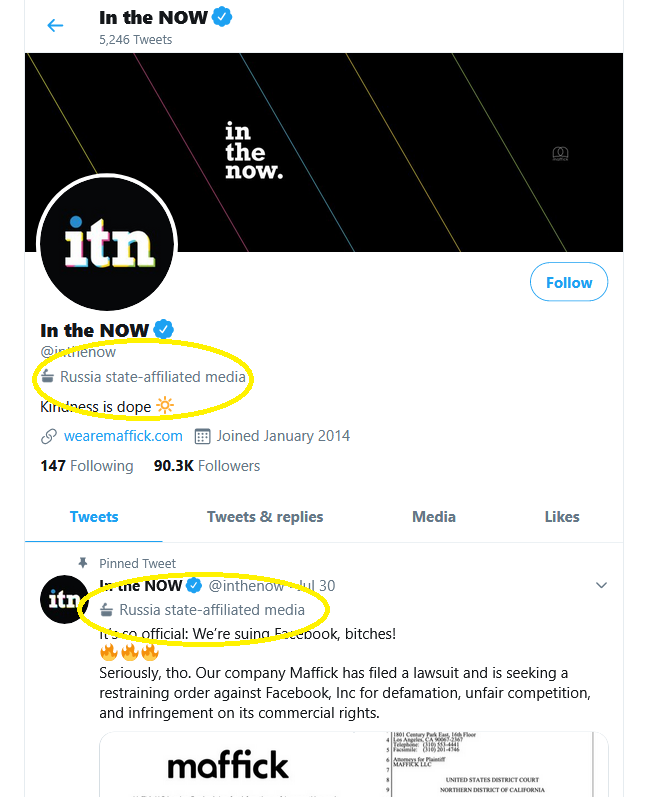

A screenshot of In the Now’s labeled Twitter account (CPJ).

One company even sued Facebook for defamation in relation to the state-controlled label in July; CNN reported that the company, Maffick, which produces English-language videos and social media posts for American viewers, had received funding from a subsidiary of Russian state news agency RT. Brand names operated by Maffick include In the Now, which shares initials with the London-headquartered media production company, ITN. Maffick CEO Anissa Naouai told CPJ via email that the company plans to hire an expert to assess its independence, and had reached out to Twitter to contest the state-affiliated label now applied to In the Now’s account and others that it operates.

The concerns arise in part because the systems are opaque and inconsistent, in placement as well as the definitions used. In CPJ’s August review of accounts run by RT, Twitter labels appeared on both profile pages and posts, YouTube labels beside individual video posts, and Facebook labels in page transparency sections of profile pages. Facebook posts are individually labeled in news feeds, but only when viewed from the U.S., according to the company’s June announcement.

“If you’re going to do it then you have to do it properly,” said Anya Schiffrin. “You have to open up and share data and provide full definitions and be completely transparent, otherwise you end up doing something that’s just cosmetic and ineffective.”

“We’re worried that a lot of the social media platforms are themselves deciding who [is] in or out and where they sit on the scale,” Sally-Ann Wilson, CEO of the Public Media Alliance, told CPJ. The group has represented public media around the world for 75 years.

“It takes a lot of skill,” she said of assessing editorial independence–since even established public media outlets may not retain it over time. “A new government comes in and it changes overnight. And I’m not sure that a lot of the social media platforms have that nuancing, have that experience.” The Alliance considers VOA public media, Wilson said. However, the recent, politically divisive appointment of a new CEO at the outlet’s parent agency, the U.S. Agency for Global Media, has raised the specter of political interference. None of the officials representing the three technology platforms would comment on whether the label applied to VOA accounts might be subject to change in future.

Yet when companies did consult experts about labeling, Wilson said, they were not always transparent about which ones—or concentrated on those from the global north.

Since June, when Facebook announced its new policy, CPJ has spoken with representatives of RT, VOA, and Al Jazeera, which have been operating under the “state-funded” label on YouTube for more than a year. None reported any change in audience engagement with their videos as a result, and it remains unclear whether labeling has any impact on media literacy.

CPJ asked representatives from all three tech platforms whether the labels were having the intended impact of educating audiences or reducing disinformation campaigns; each said they don’t track the data to make such an assessment.

Meanwhile, private owners and advertisers continue to influence media operations in ways that the labels focused only on the state fail to capture. In Turkey, for example, where CPJ has documented the steady erosion of independent news coverage via imprisonment and censorship, the state exerts significant influence over private media through direct and indirect advertising distribution, according to a Reuters Institute study.

Labeling is more art than science. And short of labeling all news media, their ownership, and funding, the classifications are imperfect—but more information about how they are made and what, if any, impact they have would help experts refine them.

“We don’t want corporate censorship and we don’t want government censorship,” said Schiffrin. “But I also feel like you have to start somewhere. The alternative is just throwing up your hands.”

Editor’s note: The description of CLS Strategies and Andrew Koneschusky’s role have been corrected in the 16th paragraph.