In 2024, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is seeking re-election for a third consecutive five-year term. The upcoming general elections in April 2024 will see India’s vast electorate, consisting of over 600 million people, exercising their right to vote.

CPJ’s Emergencies Response Team (ERT) has compiled a safety guide for journalists covering India’s election. The guide contains information for editors, reporters, and photojournalists on how to prepare for the election and how to mitigate digital, physical, and psychological risks.

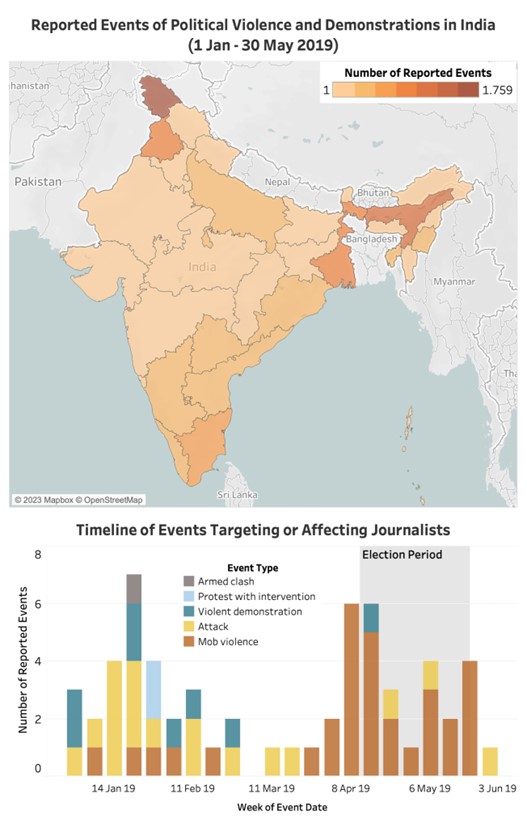

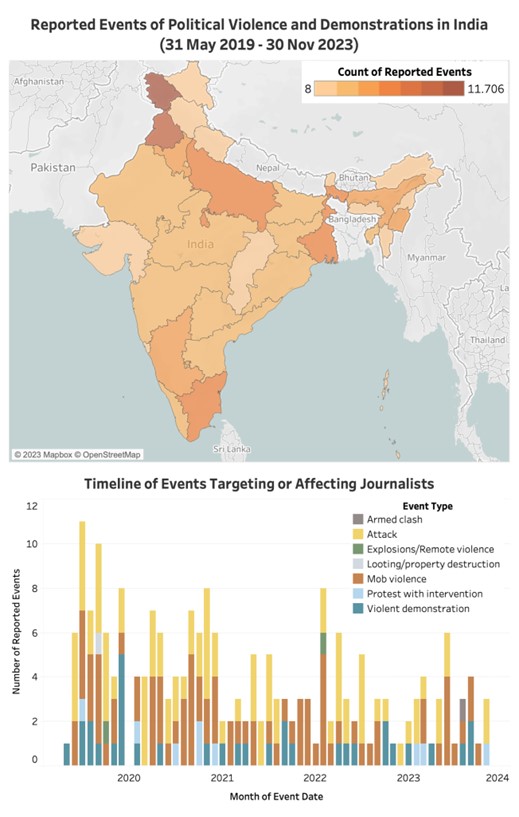

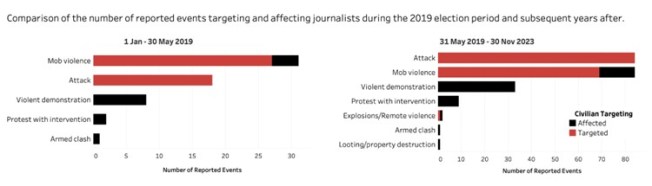

During the past several years in India, there have been instances of increased pressure on journalists, censorship attempts, and limitations on reporting, especially when sensitive political issues are involved. Based on the last general election trends and over the last five years, data from the Armed Conflict & Location Event Data Project (ACLED) reveals that there is an increasing threat to journalists from physical attacks, mob violence, and violent demonstrations. At the same time, journalists are being forced to defend themselves on the digital front with an escalation in social media trolling, online harassment, cyberbullying, and digital surveillance. As a result of these combined assaults, newsrooms and the media as a whole are also experiencing mental health stress.

Source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED); www.acleddata.com

The ACLED dataset is an event-based dataset containing disaggregated incident information on political violence, demonstrations, and select related non-violent developments around the world. ACLED data are collected in real-time and published on a weekly basis. ACLED data detail the event type, involved actors, location, date, and other characteristics of these incidents. For more detailed information on ACLED methodology, please refer to the ACLED Codebook.

Background explainer on data visualization, from Kunal Majumder

The ACLED data highlights a surge in physical violence leading up to the 2019 general elections, particularly in West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, and Jammu and Kashmir. Concurrently, CPJ documentation and media reports from that period indicate a rise in physical assaults and threats against journalists.

For instance, in February 2019, alleged Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) supporters assaulted a journalist in Chhattisgarh for recording a scuffle between party workers. In April 2019, purported Indian National Congress supporters attacked a photojournalist in Tamil Nadu for photographing empty chairs at a Congress election rally.

West Bengal experienced an alarming number of incidents, including violence against journalists, documented by CPJ on May 6, 2019. Confrontations between supporters of the ruling All India Trinamool Congress and the opposition BJP in Kolkata resulted in violent clashes in Barrackpore. Journalists covering these events faced serious threats, including instances of stone pelting at their vehicles. Unfortunately, such targeted attacks were not isolated incidents; on the same day in the Hooghly district of West Bengal, political clashes again led to journalists being targeted while reporting on the events.

These incidents underscore a recurring pattern wherein journalists become casualties of political violence, compromising their ability to report objectively and freely.

Subsequent years have seen an escalation of physical violence in other Indian states, including Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, and Manipur, according to ACLED data. CPJ documentation since May 2019 also reveals a consistent rise in violence against journalists in these states. Out of the 11 journalists killed since 2019, four were killed in Uttar Pradesh. In December 2020, an angry mob in Karnataka’s Hassan district attacked a woman journalist after she reported the existence of illegal cow slaughterhouses in the area. In September 2021, a journalist was assaulted by right-wing protesters in Mysuru, Karnataka, for recording their speech.

The evolving nature of these press-related attacks necessitates heightened attention and proactive measures to safeguard journalistic integrity and ensure the free flow of information, particularly in politically charged environments.

Safety Guide Contents

- Editor’s safety checklist when deploying staff on a hostile story

- Digital safety: The basics

- Digital safety: Basic device preparedness

- Digital safety: Spyware and digital surveillance

- Digital safety: Internet shutdowns

- Digital safety: Online harassment and targeted online campaigns

- Physical safety: Reporting safely on rallies and protests

- Physical safety: Reporting safely in a hostile community

- Psychological safety: Managing trauma in the newsroom

- Psychological Safety: Dealing with trauma-related stress

Editor’s Safety Checklist when deploying staff on a hostile story

During the run-up to the election, editors and newsrooms will be assigning journalists to stories on short notice. This checklist includes key questions and steps to consider to reduce risk for staff.

- Are your staff experienced enough for the assignment?

- Have you discussed any health issues your staff may have that could affect them during the task?

- Have you recorded and saved securely the emergency contacts of all staff being deployed?

- Does the team have the appropriate accreditation, press passes, or a letter indicating they work for your organization?

- Have you considered the level of risk attached to the story that your team may be exposed to? Is this level of risk acceptable in comparison to the editorial gain?

- Detail potential risks and measures put in place to make staff safer:

- Does the role or profile of any journalist being deployed put them at more risk? (E.g. photojournalists who work closer to the action or female journalists.) If yes, provide details:

- Is special equipment such as body armor, respirators, or a medical kit required? Do the journalists have access to the necessary equipment, and do they know how to use it?

- Are the journalists driving themselves, and if so, is their vehicle roadworthy and appropriate?

- Have you identified how you will communicate with the team and how they will remove themselves from a situation if necessary? If so, detail below:

- Have you identified the local medical facilities in case of injury? If so, record it below:

- Is the team correctly insured and have you put in place appropriate medical cover?

- Have you considered the possibility of long-term trauma-related stress?

For more information about risk assessment and planning, see the CPJ Resource Center.

Digital Safety: The basics

It’s important to know the basics of digital safety in order to be more secure both online and when using devices. The following are good best practices for journalists covering the election:

Secure your accounts

- Protect against hacking of your accounts by turning on two-factor authentication (2FA) for all online accounts. Use an authenticator app, such as Authy, instead of using SMS.

- For each account where you have 2FA turned on, ensure you have a copy of the backup codes. This will give you access to your account should you lose access to your authenticator app.

- Follow guidance for creating secure passwords. This includes using a different password on each account, creating a password that is more than 15 characters long, and ensuring that your passwords have no personal information contained in them.

- Review your accounts regularly and back up or delete content that you would not want others to access if your accounts were hacked.

- Regularly check the “account activity” section of your accounts. If a device you don’t recognize is logged in, you should log out of that particular device.

Better protection against phishing

- There is normally an uptick in phishing during election periods. Phishing messages can be used to trick you into submitting sensitive information onto a website, or they can contain links or downloads that, once clicked, may contain malware that can infect your devices.

- Be wary of messages that urge you to do something quickly or appear to be offering you something that appears too good to be true.

- Check the details of the sender’s account and the message content carefully to see if it is legitimate. Small variations in spelling, grammar, layout, or tone may indicate the account has been spoofed or hacked.

- Verify the message with the sender using an alternative method, like a phone call, if anything about it is suspicious or unexpected.

- Think carefully before clicking on links, even if the message appears to be from someone you know. Hover your cursor over links to see if the URL looks legitimate.

- Preview any attachments you receive by email; if you do not download the document, any malware will be contained. If in doubt, call the sender and ask them to copy the content into the email or take screenshots of the document in preview instead of downloading it.

Read the CPJ’s digital safety kit for more detailed information.

Digital Safety: Basic device preparedness

While covering an election, journalists are likely to be using their mobile phones for reporting and filing stories as well as being in contact with colleagues and sources. This has digital security implications if journalists are detained, and their phones are seized or broken. Raids on newsroom offices may also occur, during which devices, including computers, may be seized.

To better protect yourself:

- Know what information is on your phone or computer and how that could put you or others at risk if you are detained and your device is taken and searched.

- Before going out to report, back up your phone to a hard drive and remove or limit access to any sensitive or personal data, such as family photos, from the device you are carrying.

- Log out of any accounts and apps that you will not be using while reporting and remove them from your phone. Log out of browsers and clear your browsing history. This will better protect your accounts from being accessed should your phone be taken and searched.

- Password protect all your devices and set up your devices to remote wipe before going out to report. Remote wipe will work only with an internet connection. Avoid using biometrics, such as your fingerprint, to unlock your phone, as this can make access to your device easier should you be detained.

- Take as few devices with you as possible. If you have spare devices, then use them and leave personal or work devices behind.

- Consider turning on encryption for your Android phone. New iPhones have encryption as standard. Please check the law with regard to encryption use.

- Where possible, use end-to-end encrypted messaging services, such as Signal, to communicate with colleagues and sources. Set messages to delete after a certain timeframe.

- Install a VPN to help access sites if they become blocked. Research the law around using a VPN and look into which VPN provider has previously worked best during a partial internet shutdown.

- Have a plan for how and when you will contact others should there be a complete internet shutdown.

- Plan for an office raid and what steps you need to take to ensure that the data on the newsroom’s computers are secured.

- Have more than one copy of your newsroom’s data. Ideally, one of these copies should be stored outside the office and in a place not connected to the newsroom.

- It is a good idea to encrypt any information that you back up. You can do that by encrypting your external hard drive or flash drive. You can also turn on encryption for your devices. Ensure you are aware of any legalities around the use of encryption.

Digital Safety: Spyware and digital surveillance

Coordinated spyware campaigns, including Pegasus, allegedly have been used against journalists in India, according to research by Citizen Lab and CPJ interviews. Once installed on your phone, sophisticated spyware will monitor all activity, including encrypted messages. Israel-based NSO Group says it markets Pegasus as a surveillance tool only to governments for law enforcement purposes, and has repeatedly told CPJ that it investigates reports that its products were misused in breach of contract.

Take steps to better protect your devices by:

- Apple devices running iOS 16 or 17 have a built-in protection against spyware called Lockdown Mode. Apple users running these operating systems should turn this on to better protect their devices against spyware. You will need to restart your device to activate it.

- There is no built-in spyware protection with Android phones, and journalists who are at high risk of spyware attacks should regularly carry out a factory reset of their device. This does not guarantee that the spyware will be removed from the phone. However, Amnesty International noted in July 2021 that Pegasus appears to be removed when devices are rebooted.

If you suspect that you have spyware on your device:

- Stop using the device immediately, turn it off, and store it somewhere where the microphone and camera will pick up the least amount of your personal activity, away from work and other places where you spend a lot of time, such as your bedroom.

- Log out of all accounts and unlink them from the device.

- From a different device, change all your account passwords.

Read more about Pegasus spyware in our advisory.

Digital Safety: Internet shutdowns

Complete or partial internet shutdowns are likely to increase during the election period and have serious consequences for journalists trying to do their jobs. Turning off or limiting access to the internet means journalists are unable to contact sources, fact-check data, or file stories. Complete or partial internet shutdowns in India and their effect on the media have been documented by CPJ.

Take the following steps to try and limit the effects of a shutdown:

- Speak with your newsroom and colleagues about planning for a complete shutdown. Create a plan detailing where and when to meet in person, and how you will document and transmit information to editors without using the internet. Consider sharing landline contact details but be aware that landline calls are insecure and should not be used for sensitive conversations. Plan how you will support colleagues who may be living and working in a region or area that is likely to be affected by a shutdown.

- Print out any documents or content from online sites that you might need in advance of a shutdown.

- Provide staff with USB drives or CDs for data storage during the shutdown.

- Download and set up VPN services to help you access blocked sites during a partial shutdown. Internet service providers frequently block VPNs, so it is recommended to have a number of options available. A VPN will not help you during a complete internet shutdown.

- Have more than one way to contact others. Downloading and setting up a variety of communications apps will mean that you can change between services should one become blocked. Be aware of the security vulnerabilities that may exist with different apps. For example, some services may require you to turn on encryption rather than it being the default. During an internet shutdown, you may be forced to communicate via more insecure means, such as SMS, so be mindful of how you share sensitive data.

- Learn how you can share data using Bluetooth, Wi-Fi Direct, and Near Field Communication (NFC). These methods allow you to pair your phone with another to transmit information and do not need access to the internet. They can normally be found in the settings section of your phone. Practice using them before a shutdown occurs and understand their limitations when it comes to sharing files.

- Even if it is difficult to report in real-time, you may still be able to document what is happening. Use USBs or CDs—encrypted, if possible—to store data and hand it to colleagues and editors. Be aware that if information on these devices is not encrypted, it could be accessed by the authorities if you are detained.

For more detailed information on internet shutdowns, read CPJ’s guide.

Digital Safety: Online harassment and targeted online campaigns

Online harassment, including targeted online campaigns, can increase during elections. Media workers are often targeted by online attackers who want to discredit the journalist and their work. This can often involve coordinated harassment and misinformation campaigns that leave the journalist unable to use social media, essentially forcing them offline. Women journalists are particularly targeted and are exposed to misogynistic and violent sexual harassment online. CPJ has documented several cases of women journalists in India being subjected to this type of harassment. Protecting against online attacks is not easy. However, there are steps that journalists can take to better protect themselves and their accounts.

To better protect yourself:

- Research whether the types of stories you cover are likely to result in online harassment.

- Online abusers may try to hack your accounts. Secure your online accounts using the best practices given at the beginning of this guide.

- Attackers look for your personal data online and are likely to use that information to harass, intimidate, and threaten you. This could include doxing, when your personal data, such as your home address, is posted online with the intent to cause you harm. Ensure you look yourself up online and take steps to remove data that could make you vulnerable.

- Review your privacy settings for each account and, where possible, make sure any personal data, such as phone numbers and date of birth, is removed. Check who has access to your personal data on social media sites and review and tighten up your privacy settings.

- Look through your accounts and remove or hide any photos or images that could be manipulated and used as a way to discredit you. This is a common technique used by trolls.

- If possible, speak with family and friends about online harassment. Abusers often obtain information about journalists via the social media accounts of their relatives and social circles. Consider asking people to remove photos of you from their sites or lock down their accounts.

- Think about what steps you will take to protect yourself if you are doxed. Speak with your media outlet about online harassment and have a plan of action in place if trolling becomes serious.

During an attack:

- Avoid engaging with online harassers, as this can make the situation worse.

- If possible, put all your accounts private and stay offline until the harassment has died down.

- Check that all your accounts have 2FA activated and that you have long and unique passwords for each account.

- Document any comments or images that are of concern, including screenshots of the harassment, the time, the date, and the social media handle of the troll. This information may be useful at a later date if you need to show it to your news organization, editor, organizations that defend freedom of expression, or, where applicable, the authorities.

- Inform your family, employees, and friends that you are being harassed online. Adversaries will often contact family members and your workplace and send them information/images in an attempt to damage your reputation.

- Online harassment can be an isolating experience. Ensure that you have a support network to assist you. In a best-case scenario, this will include your employer.

For more detailed information on protecting yourself against online harassment read CPJ’s resources for protecting against online abuse.

Physical Safety: reporting safely on rallies and protests

During elections, journalists frequently work amongst crowds at rallies, campaign events, live broadcasts, and protests.

To minimize the risk:

Political Events and Rallies

- Ensure that you have the correct accreditation or press identification. For freelancers, a letter from the commissioning employer is helpful. Have it on display only if safe to do so. Do not use a lanyard but clip it to a belt.

- Gauge the mood of the crowd. If possible, call other journalists already at the event to check the mood. Consider taking another reporter or photographer with you if necessary.

- Wear clothing without media company branding and remove media logos from equipment/vehicles if necessary. Have appropriate footwear.

- Have an escape strategy in case circumstances become hostile. You may need to plan this on arrival but do so before beginning the assignment. Park your vehicle in a secure location or ensure you have a guaranteed mode of transport.

- If the climate becomes hostile, do not hang around outside the venue/event, and do not start questioning people.

- If the objective is to report from outside, working with a colleague is sensible. Report from a secure location with clear exits and familiarize yourself with the route to your transportation. If an assault is a realistic prospect, consider the need for security and minimize your time on the ground to what is absolutely necessary.

- Inside the event, report from the press area unless it is safe to do otherwise. Ascertain if the security or police will assist if you are in distress and identify your exits.

- If the crowd/speakers are hostile to the media, mentally prepare for verbal abuse. In such circumstances, just do your job and report. Do not react to the abuse. Do not engage with the crowd. Remember, you are a professional, even if others are not.

- If spitting or small missiles from the crowd are a possibility and you are determined to report, consider wearing a hooded, waterproof, and discrete bump cap.

- If the task was difficult, do not bottle up your emotions. Tell your superiors and colleagues. It is important that they are prepared and that everyone learns from each other.

Protests

To minimize the risk when covering protests:

- Plan the assignment and ensure that you have a full battery on your mobile phone. Know the area you are going to. Work out in advance what you would do in an emergency. Take a medical kit if you know how to use it.

- Always try to work with a colleague and have a regular check-in procedure with your base, particularly if covering rallies or crowd events.

- Wear clothing and footwear that allows you to move swiftly. Avoid loose clothing and lanyards that can be grabbed, as well as any flammable material (i.e., nylon).

- Consider your position. If you can, find an elevated vantage point that might offer greater safety.

- At any location, always plan an evacuation route as well as an emergency rendezvous point if you are working with others. Know the closest point of medical assistance.

- Maintain situational awareness at all times and limit the number of valuables you take. Do not leave any equipment in vehicles, which are likely to be broken into. After dark, the criminal risk increases.

- If working in a crowd, plan a strategy. It is sensible to keep to the outside of the crowd and don’t get sucked into the middle where it is hard to escape. Identify an escape route and have an emergency meeting point if working with a team.

- Photojournalists generally have to be in the thick of the action so are at more risk. Photographers, in particular, should have someone watching their back and should remember to look up from their viewfinder every few seconds. Do not wear the camera strap around your neck to avoid the risk of strangulation. Photojournalists often do not have the luxury of being able to work at a distance, so it is important to minimize the time spent in the crowd. Get your shots and get out.

- All journalists should be conscious of not outstaying their welcome in a crowd, which can turn hostile quickly.

- In Kashmir, Indian police have used live fire, rubber bullets, and pellet guns to quell protesters. Consider using personal protective equipment, but if this is not appropriate, pay attention to the police. If firearms are visible, move to hard cover and do not dwell in natural exits in case of a stampede.

To minimize the risk when dealing with tear gas:

- You should wear personal protective equipment that includes a gas mask, eye protection, body armor, and helmet.

- Individuals with asthma or respiratory issues should avoid areas where tear gas is being used. Likewise, contact lenses are not advisable. If large amounts of tear gas are being used, there is the possibility of high concentrations of gas sitting in areas with no movement of air.

- Take note of any potential landmarks (i.e., posts, curbs) that can be used to help you navigate out of the area if you are struggling to see.

- If you are exposed to tear gas, try to find higher ground and stand in fresh air to allow the breeze to carry the gas away. Do not rub your eyes or face, as this may worsen the situation. Once possible, shower in cold water to wash the gas from skin, but do not bathe. Clothing may need to be washed several times to remove the crystals completely or even discarded.

Journalists have been assaulted by protesters in India. When dealing with aggression, consider the following:

- Gauge the mood of protesters toward journalists before entering any crowd and watch for potential assailants.

- Read body language to identify an aggressor and use your own body language to pacify a situation.

- Keep eye contact with an aggressor, use open hand gestures, and keep talking in a calming manner.

- Keep an extended arm’s length from the threat. Back away and break away firmly without aggression if held. If cornered and in danger, shout.

- If aggression increases, keep a hand free to protect your head and move with short, deliberate steps to avoid falling. If in a team, stick together and link arms.

- While there are times when documenting aggression is crucial journalistic work, be aware of the situation and your own safety. Taking pictures of aggressive individuals can escalate a situation.

- If you are accosted, hand over what the assailant wants. Equipment is not worth your life.

Physical Safety: reporting safely in a hostile community

Journalists are frequently required to report in areas or communities that are hostile to the media or outsiders. This can happen if a community perceives that the media does not fairly represent them or portrays them in a negative light. During an election campaign, journalists may be required to work for extended periods among communities that are hostile to the media.

To help reduce the risk:

- If possible, research the community and their views. Develop an understanding of what their reaction to the media will be and adopt a low profile if necessary.

- Wear clothing without media company branding and remove media logos from equipment/vehicles if necessary. Have appropriate clothing and footwear.

- Take a medical kit if you know how to use it.

- Secure access to the community. Turning up without an invitation or someone vouching for you can cause problems. Hire or get the approval of a local fixer, community leader or person of repute in the community who can help coordinate your activities. Identify a local power broker who can help in case of emergency.

- At all times, be respectful to the individuals and their beliefs/concerns.

- Avoid working at night: the risk increases dramatically.

- If there is endemic abuse of alcohol or drugs in the community, the unpredictability factor increases.

- Limit the amount of valuables/cash that you take. Will thieves be attracted by your equipment? If you are accosted, hand over what they want. Equipment is not worth your life.

- Ideally, work in a team or with back up. Depending on risk levels, the backup can wait in a nearby safe location (shopping mall/petrol station) to react if necessary.

- Plan your visit. Think about the geography of the area and plan accordingly.

- Park your vehicle ready to go, ideally with the driver in the vehicle.

- If you have to work remotely from your transportation, know how to get back to it. Identify landmarks and share this information with colleagues.

- Know where to go in case of a medical emergency and work out an exit strategy.

- Consider the need for security if the risk is high. A local hired back watcher to protect you/your kit can be attuned to a developing threat while you are concentrating on work.

- It is generally sensible to ask consent before filming/photographing an individual, particularly if you do not have an easy exit.

- When you have the content you need, get out and do not linger longer than necessary. It is helpful to have a cut off time pre-agreed and pull out at that time. If a team member is uncomfortable, do not waste time having a discussion. Just leave.

- Before broadcast/publication consider that you may need to return to this location. Will your coverage affect your welcome if you return?

Psychological Safety: Managing trauma in the newsroom

Stories and situations that frequently result in distress and when you should be thinking about trauma include:

- Graphic images of violence (death, crime scenes, brushes with death)

- Large-scale accidents or disasters (train/plane/car crashes)

- Abuse cases, particularly involving children or the elderly

- Any distressing story that has a personal connection for staff

- When inexperienced staff are being exposed to such content for the first time.

Management should guide staff on such days and share the responsibility of care. The following approach should be considered and acted upon if required. The extent to which the guidance is implemented will depend on the severity of the story.

On such days:

- Try to rotate assignments around staff so that the same producer isn’t cutting footage on difficult subjects for days on end.

- Make sure that team members know that they can say no when a subject is personally distressing to them. Staff should feel able to express concerns about tackling challenging subjects, and it should be handled with sensitivity and discretion, and without further questions being asked. This represents an important exception to how videos are generally assigned.

- Make sure that your team members have breaks in between edits and are able to get fresh air when working on difficult material.

- Ask people if they are OK early and often—and not just via text message. You should check in with your staff at least once or twice a day verbally to make sure that everyone knows you are available to chat. Conversation between staff on the issue should be encouraged.

- If your team isn’t involved in these areas, be generous with lending team members to help out other teams during particularly stressful periods.

- On particularly stressful days, try to ensure there is a debrief before everyone leaves the work environment.

- At the debrief, the responsible manager should acknowledge that people may be distressed by the story, and it’s perfectly natural in the short term. If staff are affected, they should talk to one of their managers. Talking to their colleagues can also help.

- If they would rather speak to an impartial adviser in confidence, is there an employee assistance program (EAP) or counselor they can speak to?

Psychological Safety: Dealing with trauma-related stress

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been increasingly acknowledged as an issue confronting journalists who cover distressing stories.

Traditionally, the issue is associated with journalists and media workers in conflict zones or when they are exposed to near-death or highly threatening situations. However, more recently, there is a greater awareness that journalists working on any sort of distressing story can experience symptoms of PTSD. Stories involving abuse or violence (crime scene reporting, criminal court cases, or robberies) or stories that involve a large loss of life (car crashes/mine collapses) are all potential causes of trauma among those covering them. Those being abused online or trolled are also vulnerable to stress-related trauma.

The growth of uncensored user-generated material has created a digital front line. It is now recognized that journalists and editors viewing traumatic imagery of death and horror are susceptible to trauma. This secondary trauma is now known as vicarious trauma.

It is important for all journalists to realize that suffering from stress after witnessing horrific incidents/footage is a normal human reaction. It is not a weakness.

For everyone:

- Talk about it. Everyone from senior management to the most junior producers is affected by dealing with difficult events, graphic footage, or challenging conditions. Talk to your manager or to another supervisor, talk to the person you sit next to. Don’t suffer in silence.

- Remember, it’s not in any way career-limiting to say that you need a break either in between videos, from a particular story, or from working in the field.

- Don’t look at graphic footage before you sleep, and don’t hit the bar too hard after a difficult news day. Disrupted sleep can harm the recovery process.

- Exercise and meditation are your friends here, as is maintaining a healthy diet and staying well hydrated.

- Remember that video doesn’t have to be graphic to be distressing. Footage involving blood or violence requires obvious care, but particularly emotive testimony can also be draining, as can videos of verbal abuse. Different people find different things challenging and distressing, so be sensitive.

- Take your comp days if you’ve worked through weekends or significantly over your hours on multiple days, whether editing or in the field. Take at least some of them quickly because you need to spend that time recovering.

For editing producers:

- Don’t watch more than you need to. Certain upsetting footage will be broadcast, but don’t watch it because you feel you have to prove yourself. Have conversations with your supervisor or manager early on about how to treat the footage so you don’t have to watch it over and over, only for it to get cut.

- When showing your supervisor, a manager, or a member of the legal team a particularly graphic or distressing video, always forewarn what they are looking at. E.g., “Do you mind looking at a video showing the immediate aftermath of a violent attack?” rather than “Do you mind looking at my video?” Footage is always significantly more upsetting if you don’t know what’s coming.

- Develop a routine. Something as simple as putting both feet firmly on the floor, taking deeper breaths than normal just before watching something particularly difficult, and having a stretch afterward can work. Find a routine that works for you.

- If you have a project that requires continued daily exposure to difficult footage, then talk about it. Acknowledge the effect that it’s having on you and think actively about how you’re going to look after yourself while you do that work.

For producers in the field:

- Remember that it’s perfectly normal to feel helpless or upset that you couldn’t do more when covering upsetting stories. Just acknowledge how you’re feeling to your colleagues, or someone else you feel comfortable with. Talking about it rather than avoiding it is often the key.

If it’s particularly intense:

- It’s normal to feel jumpy or anxious or to replay difficult images in your mind immediately after an event. Admitting how you’re feeling is useful, as is taking a bit of time out, even if it’s just a short break.

- If these feelings aren’t passing in the days and weeks after the events, it’s worth flagging it to your seniors. If it feels particularly overwhelming, it’s better to seek help sooner.

Journalists requiring assistance can contact CPJ Emergencies via emergencies@cpj.org or CPJ’s India Representative Kunal Majumder at kmajumder@cpj.org. For more information on journalist safety during elections visit Journalist Safety: Elections.