The Ebola crisis in West Africa is unrelenting, and journalists on the frontline of reporting on the virus are caught between authorities wanting to control how the outbreak is reported, and falling victim to the disease themselves.

Liberia’s media is in a fight for survival, with its government continuing its clampdown on the press which began after the first cases of Ebola were reported there in March, according to CPJ research and interactions with local journalists and rights activists.

On September 30, the government announced it was taking over the issuing of accreditation for both local and international journalists to practice in the country, according to news reports. The Press Union of Liberia has accused the government of going against a Memorandum of Understanding signed in the early 1990s between the PUL and the government, in which the PUL was put in charge of accrediting individual journalists, while the government, through the Ministry of Information, registered media houses, the reports said. The government has reneged by saying the memorandum is not backed by any statutory law, government spokesman Isaac Jackson responded.

On October 2, the government announced new media restrictions barring health workers from speaking to the press, and requiring all local and foreign journalists to obtain official written approval before contacting and conducting interviews with patients, or recording, filming or photographing healthcare facilities, according to news reports. Journalists without this permission are at risk of arrest and prosecution, the reports said. Health officials said the restrictions were necessary to protect the privacy of patients and health workers, and applied to local and international journalists, according to news reports.

President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, in an October 1 letter to Parliament also requested additional powers to restrict movement and public gatherings, and the authority to appropriate property “without payment of any kind or any further judicial process,” The Associated Press reported. The president, citing the need to bolster the fight against Ebola, sought the suspension of several articles in the Liberian constitution including freedom of expression and the press, movement, labour rights, and religion. Lawmakers, some warning the country risked turning into a police state, rejected the request, Tennen Dalieh, program assistant at the Center for Media Studies and Peacebuilding in Liberia, told me.

Sirleaf’s request in Parliament came on the heels of a three-month state of emergency imposed on August 6 where, in a televised speech, Sirleaf warned of the use of “extraordinary measures,” including suspending citizens’ rights, in the bid to contain the virus. Liberia has the highest casualty with 2,458 deaths out of 4,493 confirmed, probable and suspected deaths linked to Ebola, recorded in seven countries worldwide, according to World Health Organisation figures published October 15.

Dalieh recounted to me how “this is becoming a way of life; the sound of sirens, trucks loaded with bodies.” Mae Azango, a CPJ International Press Freedom Awardee and journalist with the independent FrontPageAfrica, said she has witnessed the incremental pile-up of bodies, at times nearing 100 daily, being deposited for cremation at the only crematorium in Monrovia which belongs to the Indian community. “I am frightened! It is worse than anything you can imagine,” Azango told me. “People are dying on a daily basis. We are dying Peter! We are dying, on a daily basis!”

The news that three Liberian journalists died from Ebola is a reminder of the risks the press can face. The PUL announced the deaths of Cassius Saye, a cameraman at Real TV, and Alexander Koko Anderson, a contributor to Liberia Women Democracy Radio, who both died in October, according to news reports and local sources. Freelance journalist Yaya Kromah died in September, the reports said. It is uncertain in what circumstances all three contracted the disease, local journalists told me.

With Ebola making headlines around the world, international news outlets have deployed journalists to cover the story in West Africa. Ashoka Mukpo, an American freelance journalist who was working for the U.S.-based NBC News, contracted Ebola in October, according to news reports. Mukpo is among at least five Americans evacuated to the U.S. for treatment after contracting Ebola in West Africa, news reports said.

“Now that I’ve had first-hand [experience] with this scourge of a disease, I’m even more pained at how little care sick West Africans are receiving,” Mukpo tweeted on October 13.

In Sierra Leone, two journalists have died from Ebola, according to news reports. Victor Kassim, a journalist at the Catholic station Radio Maria, died in September, news reports said. His entire family, including his child and wife, who worked as a nurse, succumbed to the disease, Kelvin Lewis, president of the Sierra Leone Association of Journalists (SLAJ), told me. Mohamed Mwalim Sheriff, a journalist with Eastern Radio, died in June, according to news reports. One account said that at the onset of the Ebola outbreak Sheriff had interviewed a Muslim cleric who cared for a patient, Lewis told me. Sheriff may have contracted the disease during the burial of the Ebola patient, he said.

With the epidemic rising despite a state of emergency, the Sierra Leone government embarked on a three-day lockdown of the country on September 19 to allow health workers to go door-to-door to educate the public and locate Ebola victims. This led to the discovery of 130 new cases, according to news reports. In the midst of the ravaging disease, journalists showed how the press can help a nation in crisis. With radio the main source for information, the media dedicated hours of broadcast time to enlighten the public about the virus.

“We started doing our own messages and broadcasting. We started by giving up free advertising space in our newspapers and giving up 30 minutes airtime free on the radio for Ebola messages,” Lewis told me.

The Sierra Leone government has openly congratulated journalists and acknowledged the positive contribution of the media to end Ebola, and called for the media’s continued partnership to combat it, according to news reports. This is a stark contrast to how the government initially accused journalists of spreading rumors about Ebola, before the disease spiralled out of control and led to the sacking of Health Minister Miatta Kargbo, Lewis told me.

The SLAJ, with support from the government, U.N. agencies and the U.S., has been organising training for journalists on how to report responsibly on the virus, according to news reports. Lewis explained how messages that Ebola had no cure were reframed to enlighten people that survival is possible if they seek help early. Such messages helped abate suspicions from the public on the intentions of the government to quarantine them, with many believing that because there is no cure they would die.

Even legislators had to rethink fighting the media over reports that questioned how $1.7 million in funds to fight Ebola in their constituencies was being utilised, according to media reports.

“Parliament summoned me twice and they saw reason for their focus to be on stopping Ebola and not journalists whose responsibility, I explained, is to report the concerns and important issues the public raises, including money meant for fighting Ebola,” Lewis told me.

In Guinea, CPJ reported the deaths of journalist Facely Camara, of Liberte FM, and Molou Cherif and Sidiki Sidibe, media workers with Radio Rurale de N’Zerekore, and five others in September. They were killed by a mob while covering a public health awareness campaign in villages. The BBC reported that many villagers accused health workers of spreading Ebola. Three weeks after their death, soldiers prevented a team of journalists and lawyers who had obtained official permission to investigate the murders, to enter the village, Radio France International reported. Their equipment was seized and, when it was returned, recordings and photos had been deleted, the report said.

The lack of education about Ebola poses a great threat to the eradication of the virus. The effect is the alarming increase worldwide in the stigmatisation of citizens from Ebola-affected countries, which the U.N.’s high commissioner for human rights, Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, has warned against, according to news reports. On October 13, Cameroon authorities deported three Sierra Leone sports journalists and two sports ministry officials who arrived in Yaoundé on October 8 to cover international soccer matches between the two countries, according to news reports. Cameroon police and immigration officers barred BBC correspondent Mohamed Fajah Barrie, and Frank Magnus Ernest Cole and Mohamed Kelfala Sesay, both journalists with Mercury Radio, from leaving their hotel because the Sierra Leone Football Association had not included their names in the official list of delegates declared free of Ebola, Barrie told me.

“We were humiliated. It was very disgraceful,” Barrie said. “We were confined at the hotel, isolated at the airport, and escorted even up to the entrance of the plane.”

African governments have called on the world to assist in the fight against Ebola; a plea being taken with more seriousness since its discovery in countries outside Africa, including the U.S. and Spain. The U.N. Security Council in an October 15 statement has however warned that the world’s response to Ebola “has failed to date to adequately address the magnitude of the outbreak and its effects.”

With the world focusing on countries stricken with Ebola, any government seeking to supress the media at this time will surely be viewed as having misplaced priorities. Sierra Leone, which has received international commendation for its efforts, seems to understand this. Liberia could do more to use the press to help its efforts.

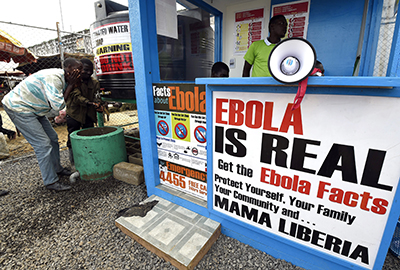

The implications for reporting on Ebola are clear, and public enlightenment campaigns by the media, such as the Ebola page on the independent FrontPageAfrica‘s website, are steps in the right direction. Journalists and their employers however, must also think about their safety and well-being when reporting on the virus. CPJ has advice on covering epidemics in its Journalist Security Guide, which is available online in several languages.

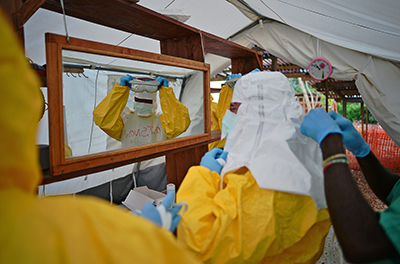

There is a distinct difference in the protective measures being taken between local and internationals journalists covering Ebola in West Africa. Stringent precautions taken by international media outlets include providing disinfectant sprays, surgical gloves, boots, plastic overalls and bio-hazard kits, according to news reports. The BBC reported having a bio-hazard expert working alongside its journalists in Sierra Leone as part of its risk management. But what are the options for less sophisticated local media outlets, many of whose journalists are poorly paid and barely have necessary working journalism tools?

“We don’t have any of those protective measures like the foreign media. We are just making sure that we follow the rules–no touching, wash your hands with chlorine, don’t get too close to people,” Lewis said.

In Liberia, Azango explained to me how journalists like her have been left to provide their own protection. “Where will journalists get hazard kits when even health workers don’t have enough and the government doesn’t want us to report?” Azango asked. “We are on our own. I wear a long-sleeve coat, put on rain boots, and have a hand sanitizer in my bag when I go reporting. That’s all.”

For journalists, media professionals, and news outlets, the price of telling the important stories around this epidemic ravaging West Africa should not come with the cost of lives. Journalists worldwide have begun sharing their experience and ways they are covering Ebola, according to news reports. Yet, the death of media workers is having a deflating effect on the morale, journalists repeatedly told me.

For Liberian authorities, the necessity of a working relationship with the media cannot be overemphasized. The government would do well to start forging a united front with the media and other actors. This is a first step to ensuring the collective survival of its citizens.