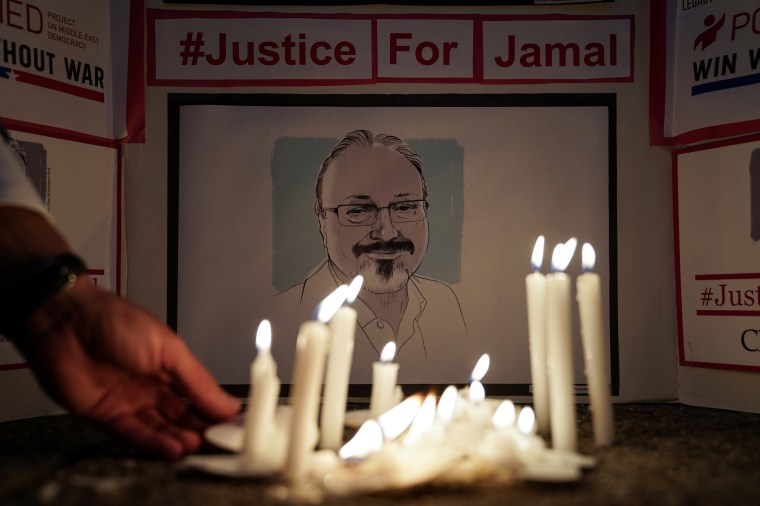

From pariah to potential partner. That’s how far Saudi Arabia has come for President Joe Biden in the five years since Riyadh sent a death squad to butcher journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

The administration’s ongoing rehabilitation of the petrodollar kingdom and its de facto ruler Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, widely known as MBS, seems to put realpolitik above Biden’s stated aim of justice for the Washington Post columnist.

The consequences of ignoring this commitment for short term strategic and economic gain are disastrous for journalists and human rights defenders not only in Saudi Arabia but globally.

Global Impunity Index 2023 Table of contents

The failure to pursue justice for Khashoggi, a U.S. permanent resident, signals to repressive regimes that even the most powerful Western democracies will temper their fervor for the protection of journalists if they perceive political and economic interests are at stake.

If someone as prominent as Khashoggi can be dismembered in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul with apparent impunity, what chance do less well-connected journalists stand if they challenge autocrats through their reporting?

The walls of newsrooms around the world are papered with the pictures of colleagues slain by governments or organized crime seeking to silence truth-telling. In eight out of 10 of these cases, those who ordered the killings escape justice.

For a moment it seemed Khashoggi’s murder might be different. The sheer grisliness of the crime where a 15-man hit team cut up the body, captured international headlines.

Even the assertively pro-Saudi Trump administration was moved to act as Turkish intelligence, which had bugged the Istanbul consulate, trickled out details of the October 2, 2018, assassination.

President Donald Trump imposed sanctions on some Saudis linked to the killing, but stopped short of accusing the crown prince directly even after U.S. intelligence concluded that he had approved the murder.

The following year, candidate Joe Biden vowed during a Democratic Party election debate to seek accountability and make Saudi Arabia a “pariah”.

On entering the White House in 2021, Biden released the unpublished CIA report but, like his predecessor, Biden balked at sanctioning MBS directly. In November last year, his administration went as far as to declare that the crown prince was shielded by sovereign immunity. That effectively killed a civil lawsuit filed in U.S. district court by Khashoggi’s fiancée, Hatice Cengiz, that sought to hold Mohammed bin Salman and two of his senior aides liable for the death.

Secure in the knowledge that Western governments would take no action against him, Prince Mohammed set about rebranding himself as a tech-friendly millennial and political reformer.

According to The Guardian, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has poured more than $6 billion into international sports deals and sponsorships, a ploy critics call sports washing. It has also wooed Silicon Valley tech companies and plans to spend $500 billion developing a futuristic city along a strip of Red Sea coast as a business and tourist destination.

The crown prince’s popularity has grown at home as he loosened religious restrictions on social life and allowed women to drive.

But behind the public relations campaigns, the kingdom remains one of the least free countries in the world, according to U.S. rights watchdog Freedom House. Some 11 journalists were in jail as of December 1, 2022, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists’ annual prison census, along with dozens of human rights defenders and social activists. Criticism of the government and the crown prince is dangerous, even when voiced by Saudi nationals who have fled abroad.

“All of us who have been calling for justice for Jamal feel let down,” Fred Ryan, former publisher and CEO of the Washington Post told me. “A Republican administration concluded that the responsibility for this went all the way to the top of the Saudi government. Candidate Joe Biden described MBS as a pariah. The question is what’s changed?”

The answer, in part, may be Washington’s calculation that it needs Saudi Arabia to counter Iranian and Chinese influence in the Middle East and to ensure greater oil market stability following the upheavals caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The administration is also trying to persuade Prince Mohammed to recognize Washington’s most important regional ally, Israel in a deal, which could be modeled on the Abraham Accords that Trump brokered between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Morocco.

Saudi Arabia is demanding a high price in return, including a mutual defense treaty, and U.S. help building a civilian nuclear program. The unprecedented, deadly assault on Israel on October 7 by Palestinian Hamas and Israel’s response have slowed – if not put paid to – any such ambitious a peace deal.

But the crown prince’s willingness to even consider such a proposal is a reminder that the United States still has leverage. Washington can promote human rights and still pursue its strategic and economic interests in the region.

If Riyadh wants U.S. security guarantees or Western support in its bids to host major events such as FIFA’s 2034 World Cup or the Olympic Games, then liberal democracies can use those opportunities. They can call for the release of jailed journalists and political prisoners at home and an end to the harassment of Saudi critics abroad.

Washington could give force of law to the visa restrictions of the U.S. State Department’s Khashoggi Ban. It can also back initiatives such as Congressman Adam Schiff’s bill to protect exiled dissidents from their home governments.

Brushing Khashoggi’s murder under some diplomatic rug is a mistake.

“Despots watch how the U.S. responds when fundamental rights that we believe in are violated,” said Ryan. “The signal that they are receiving is not an encouraging one.”