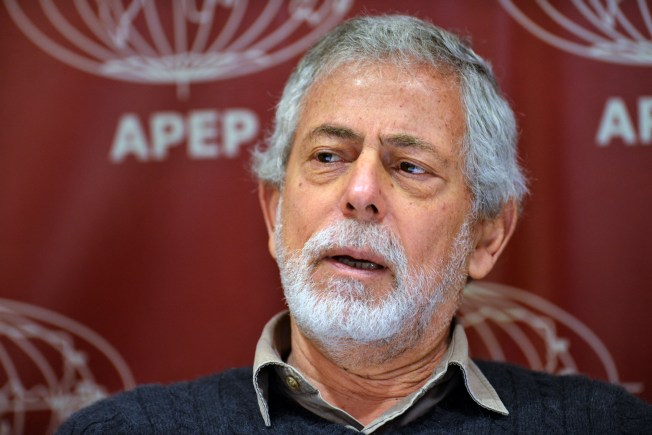

Journalist Gustavo Gorriti remembers the days — just a few years ago — when people on the streets of Lima approached him to congratulate him for exposing corrupt government officials, drug trafficking mafias, and human rights abusers. A few even asked him to pose for selfies. These days, though, motorists shout insults at him from their cars. He’s been told that he faked his 1992 kidnapping and that he belongs in prison. He gets dirty looks and faces an avalanche of online abuse.

Gorriti, the founder and editor-in-chief of the award-winning Lima-based investigative news website IDL-Reporteros blames the backlash largely on La Resistencia, or “The Resistance,” an ultra right-wing group that has picketed the homes and offices of prominent journalists, politicians, and human rights activists, claiming they are pushing Peru towards communism and chaos. The group has also disrupted book events and news conferences and has clashed with left-wing protesters. Critics describe its members as bullies and shock troops at the service of right-wing politicians.

La Resistencia has staged about 20 raucous protests outside the office of IDL-Reporteros and in front of Gorriti’s home over the past five years. The group was recently at the center of a small political earthquake in Peru; its July 10 meeting with Deputy Culture Minister Juan Reátegui caused such an uproar among the Peruvian press corps that Reátegui was fired the next day.

The press had good reason to object: through loudspeakers and bullhorns, La Resistencia members have hurled death threats and antisemitic slurs at Gorriti, who is Jewish. They insist that IDL-Reporteros produces fake news and that, instead of divulging wrongdoing by the powerful, Gorriti and his team of journalists are themselves the corrupt ones.

These falsehoods are magnified on social media and by right-wing outlets in Peru, like TV station Willax and the daily newspaper Expreso. All this, Gorriti says, reduces the impact and traction of IDL-Reporteros’ investigative journalism.

“It’s an accumulation of lies that amounts to character assassination,” Gorriti, 75, said in an interview last month in his cramped office in Lima. “We must never underestimate the power of disinformation.”

Gorriti isn’t the only one who sees the rise of La Resistencia as ominous for press freedom in Peru, which was already under stress amid a rising number of criminal defamation lawsuits filed against journalists and attacks on dozens of reporters during anti-government protests earlier this year.

So far, none of the targeted journalists has been physically attacked by La Resistencia but they fear this could be the next step.

“La Resistencia is made up of fanatics who foment violence and intolerance on behalf of the worst elements of Peruvian politics,” said Antonio Zapata, a Peruvian historian and columnist for La República, a Lima newspaper that has been targeted by the group.

La Resistencia was founded in 2018 by Juan José Muñico, a 47-year-old metalworker from a working-class neighborhood of Lima. A 2020 investigation by IDL-Reporteros said that when Muñico was 22, he was questioned in a 1998 murder case of a Peruvian army soldier; Muñico was never charged and the case remains unsolved.

In a rare interview, Muñico told CPJ that he formed La Resistencia, which he said counts some 150 members, in response to what he and others viewed as an alarming leftward drift in Peruvian politics and society. He said former police officers and military personnel are part of the group which supports conservative family values. Its slogan is: “God, homeland, and family.”

La Resistencia often targets independent Peruvian media outlets and journalists who have reported on corruption scandals involving right-wing politicians and on human rights abuses carried out by the police and military. Muñico claims that many of these reports are either exaggerated or false.

“The media manipulates information all the time,” he told CPJ. “So, we began to identify the journalists who are saying these things.”

La Resistencia’s most frequent target is IDL-Reporteros, the journalism wing of the Legal Defense Institute, an independent organization dedicated to fighting corruption and improving justice in Peru. Last year, the institute won a defamation case against Muñico.

Since 2015 IDL-Reporteros has published a series of exposés about corruption within Peru’s judicial system and about Odebrecht, a Brazilian construction firm that admitted to paying $800 million in kickbacks to politicians across Latin America in exchange for public works contracts.

Partly as a result of IDL-Reporteros’ scoops, dozens of Peruvian public officials, lawyers, judges and business people are under investigation for criminal acts, including failed presidential candidate Keiko Fujimori and other right-wing politicians that La Resistenciasupports.

Keiko Fujimori is the daughter of Alberto Fujimori, the former president who is serving a 25-year prison sentence for human rights violations and abuse of power. Muñico told CPJ that Fujimori, whom he credits with bringing security and economic stability to Peru during his time in office, was the inspiration for his own foray into politics, which included an unsuccessful campaign for a congressional seat in 2020.

Fujimori’s daughter is under investigation for money laundering, a case that has been extensively covered by IDL-Reporteros.

“That’s why La Resistencia is defaming us,” said Glatzer Tuesta, director of the Legal Defense Institute and a journalist who works closely with Gorriti.

The group’s largest protest occurred on May 5, when about 50 members of the group set off small explosives, lit flares, and threw bags of trash and broken glass at the IDL-Reporteros office. Some of the demonstrators shouted threats, including “Gorriti, your days are numbered” and “Gorriti: you will die.” After Gorriti filed a complaint, the attorney general’s office opened a preliminary investigation of Muñico and other members of La Resistencia for harassment and disturbing public order, Carlos Rivera, IDL-Reportero’s lawyer, told CPJ.

On February 21, the group protested outside of Gorriti’s home in Lima then marched to the nearby house of Rosa Maria Palacios, a columnist for La República who also hosts radio and TV news programs. Palacios said she was targeted in response to her reports criticizing the police for killing protesters during a wave of unrest that broke out in December 2022 following the ouster of then-President Pedro Castillo, a leftist despised by La Resistencia.

“Because I was explaining these things to the public I ended up with a mob at the door of my house,” Palacios told CPJ. “There were about 20 people with bullhorns calling me a terrorist, and a communist and a dirty pig.”

Jaime Chincha, a well-known Peruvian TV journalist who has also been targeted by La Resistencia with protests, told CPJ that while police officers monitor La Resistencia activities they do not intervene. He believes that the police have come under pressure from the right-wing government of President Dina Boluarte to give the group free reign.

The Peruvian police did not respond to CPJ’s requests for an interview to discuss La Resistencia. A police source, who did not want to be identified because he was not authorized to speak to the press, said his commanders “are not going to talk about it because it’s an extremely delicate issue within the police.”

Alberto Otárola, Boluarte’s cabinet chief, told reporters after the deputy culture minister’s meeting with the group that the government respects press freedom and “deplores any initiative by people or groups that tries to normalize violence and assaults the dignity and security of people.”

For his part Muñico, the founder of La Resistencia, says there’s no reason for the police to intervene. “We protest outside,” he said, denying that the demonstrators intend to intimidate journalists from doing their jobs. “It’s not like we’re burning down their houses.”

Still, La Resistencia counts other friends in politics. At a seminar organized by the group last year, lawyer and right-wing politician Ángel Delgado extolled the group, saying, “you are fundamental for Peru’s democracy.” Another supporter, according to Gorriti and news reports, is Lima’s right-wing mayor, Rafael López Aliaga.

Chincha and Gorriti insist that the constant harassment is illegal and could, in some cases, be qualified as hate speech. Roberto Pereira, a Lima lawyer who often defends journalists, told CPJ that “when La Resistencia alters public order, it’s no longer free speech.”

Last year, the Legal Defense Institute won a criminal defamation lawsuit against Muñico, who was ordered to pay the outlet 10,000 sols (US$2,754) and was given a one-year suspended prison sentence. Muñico currently faces another defamation lawsuit stemming from remarks he made about a Peruvian human rights group and the Legal Defense Institute, which he called a “criminal organization.”

When La Resistencia began targeting him in 2018, Gorriti said he tried to stay focused on investigative journalism. But now he says debunking the group’s disinformation campaign is his top priority.

To that end Gorriti organized a rally on June 6 to defend IDL-Reporteros. Supporters banged on drums, unfurled banners, and shouted slogans denouncing La Resistencia. Near the end of the hour-long event, Gorriti grabbed a microphone and addressed the crowd.

La Resistencia and its allies “attack independent journalism because they are trying to impose an empire of lies,” he said. “But we will defend journalism with our lives and do all we can to provide people with the truth.”