Justice remains elusive six months after the killing of prominent Pakistani journalist Arshad Sharif in Kenya on October 23, 2022. Kenyan authorities claimed Sharif was shot dead by Kenyan police in an incident that shocked Pakistan’s media community and raised questions about whether his death was connected to his work. “This was a targeted killing,” his wife of 11 years, Javeria Siddique, told CPJ via video call ahead of the half-year mark of Sharif’s death.

Kenyan national police said Sharif, an anchor with Pakistan’s ARY News, was shot by a police officer after the driver of Sharif’s car did not stop at a roadblock set up outside the capital of Nairobi during authorities’ search for a stolen motor vehicle.

Sharif had sought safety in Kenya after fleeing Pakistan in August 2022, following his ARY News interview with Shahbaz Gill, a close aide to former Prime Minister Imran Khan, who was ousted from power in a parliamentary no-confidence vote in April 2022. Gill was arrested on charges of sedition for comments made about the army during the interview and ARY News channel was taken off the air. Earlier in the year, Sharif was named as one of several Pakistani journalists being investigated by authorities because of their journalistic work.

In December 2022, Pakistan’s Supreme Court took notice of the case and ordered a government investigation into Sharif’s death. In a December report, a Pakistan government fact-finding team (FFT) found that the Kenyan police portrayal of the killing as a case of mistaken identity was “full of contradictions” and that the involvement of “characters in Kenya, Dubai, and Pakistan in this assassination cannot be ruled out.” The team also noted that a Pakistan post-mortem report had documented numerous injuries on Sharif’s body, including four missing fingernails, hand wounds, and a broken rib, but that the investigation had found “no concrete evidence” to establish that Sharif was tortured before his death.

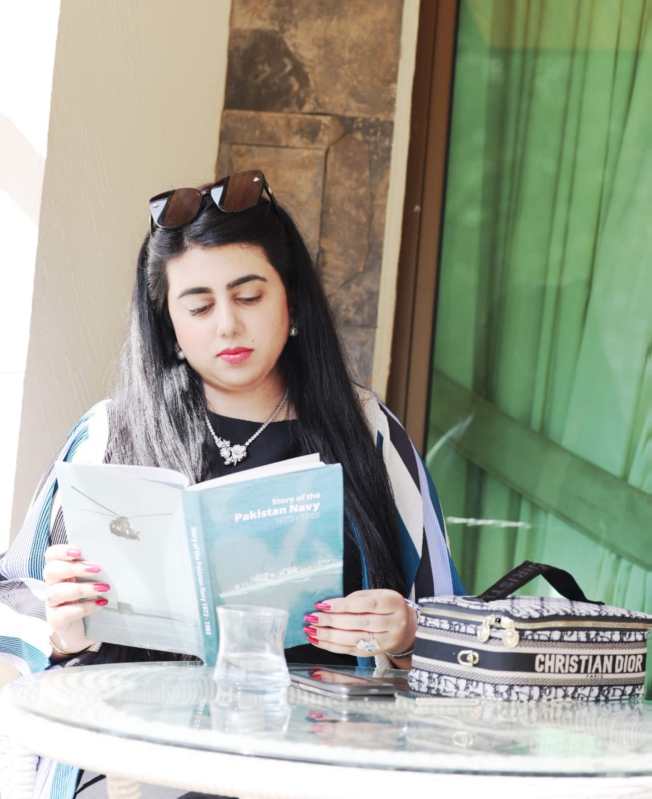

Siddique, a freelance journalist and photographer, spoke with CPJ about the lack of justice for her husband and her hopes for how the international community can help. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us about your husband’s work as a journalist in Pakistan. What caused him to flee the country?

He covered mainly defense-related stories and then investigative journalism. Even he faced social media harassment in the Imran Khan era. But things completely changed when the government shifted from Imran Khan to [current Prime Minister] Shehbaz [Sharif]. [Arshad] was booked in 16 fake cases of treason and sedition. He was going to courts daily.

He was not willing to leave the country. I have noticed so many plainclothes people outside our house from CCTV cameras who were spying on him and wanted to know about his movement from office to house. I remember on those days, his movement was only confined to the office and the house, and he was not meeting that many people. Powerful [figures] asked his channel to stop his show and sack him from the channel.

He was threatened in Pakistan: “If you are not going to stop exposing [the] corruption of the ruling elite in Pakistan, we will shoot you in the head.” There was some circular by the [Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provincial] government that [said the] Taliban is going to assassinate him.

He left suddenly, and he called me from the airport [en route to Dubai]. He said, “I am leaving; no need to worry, just relocate and save your gadgets. Put your cash and jewelry somewhere safe.”

How did he end up leaving Dubai and arriving in Kenya?

Someone from the Pakistani embassy and someone from Dubai police came into his hotel and said to him, leave the country. Otherwise, they were going to deport him back to Pakistan. We were so scared because he didn’t have any visas on his passport, and as a Pakistani, you do not have many options for on-arrival visas. On 20 August, he landed in Kenya, and he never told his mother or me his location. He was doing a daily vlog [on his YouTube channel] and exposing [the] corruption of the ruling elite in Pakistan.

Then he told me on the phone, “There is an order to kill me, so I am very careful.” Then I said, “Who is giving you these threats?” He said, “I will tell you, but my life is in danger, so I am hiding.”

He wrote to the Pakistani president and the Supreme Court [about the threats] in 2022. He raised his concern that his life was in danger, but no one gave him help at that time, and later he was killed in Kenya. It was because of his journalistic work.

Do you believe Pakistan’s investigation teams have conducted impartial and thorough probes?

No one has been arrested in Pakistan. No one has been arrested in Kenya. The FFT found out a few things, and I agree on those points. But the new JIT [joint investigation team formed by Pakistan’s government in December following an order by the country’s Supreme Court] is just an eyewash. Our government is not serious about getting justice for Sharif because he was their worst critic. Investigations are very slow. JIT never shared their report with us.

Kenya affirmed in a March report that the killing was a “case of mistaken identity,” a claim disputed in the Pakistan FFT’s report. What is your response?

They are saying it’s a case of mistaken identity and it was not a targeted assassination. How is this possible? Why have they targeted a journalist who was hiding there?

They are not cooperative with us. I have written a letter to the Kenyan president, but there was no response. I requested phone forensic of [the two Pakistani brothers who hosted Sharif in Kenya, one of whom the FFT found to be in contact with the Islamabad sector commander of Pakistan’s military intelligence agency]. But it has not been done.

I have some questions for Kenya. Did they receive any instructions or payment for the killing? If there was any suspicion [about the car being stolen], why did they not hit the car’s tires? Why did they not hit the other passenger, who was sitting at the next seat? Arshad was not driving the car. The other thing is that he was not given any kind of medical treatment. He was brought straight to the mortuary. Why was he not given a chance to live?

Can you tell us about the online smear campaign you have been subjected to in recent months?

In November I faced this, but I was in extreme trauma, so I was not focused on [social media]. This time in February, there was a planned, designed campaign against me to hurt me and break me emotionally. It was everywhere.

Religiously, we have to follow a four-month [and] 10 days mourning period for the husband. But the trolls accused me that I got married during this time and that I broke Islamic laws, which I never did. I am still a widow. I am still waiting and seeking justice for my husband.

For six months, I have never gone to the market. Every time a motorbike approaches my car, I always think, “Is he going to assassinate me? Is he going to harm me?” I’m facing lots of health issues not just because of the worst kind of harassment, but [because] to live without my husband is the worst kind of punishment.

I have started my work again. I feel that I have to earn and remain independent.

He is gone, but I am dying every day because of the delay in justice, the hate campaigns, the harassment.

What do you want to see next in your fight for justice for Sharif?

From day one, we have been requesting the United Nations to appoint an investigation team in this case because [Pakistan and Kenya] are not serious in giving us justice. The U.N. should ask both countries to expedite these investigations and appoint a rapporteur on this case. They helped the family of [Saudi journalist] Jamal Khashoggi, even [Palestinian American journalist] Shireen [Abu Akleh].

There are three countries [involved] in this murder. How can I, as a widow, travel to each country to seek justice? I want the international community, especially our journalistic bodies, to be my voice in this case and remind them that we never got justice.

CPJ called and messaged Marriyum Aurangzeb, Pakistan’s information minister; Malik Ahmad Khan, spokesperson for Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif; and Major General Ahmed Sharif Chaudhry, director general of the Pakistan military media wing, but did not receive any replies. The press wing of Pakistan President Arif Alvi’s office and the Pakistan embassy in the United Arab Emirates did not respond to CPJ’s emailed requests for comment.

CPJ also called and messaged Japheth Koome, inspector general of the Kenyan police and Resila Onyango, the national police spokesperson, but did not receive any replies. CPJ’s calls to Noordin Haji, director of public prosecutions, did not connect and message did not receive a response.

Hussein Mohamed, spokesperson for the office of Kenyan President William Ruto, and Francis Gachuri, spokesperson for the Kenyan Ministry of Interior, said the case was still under investigation and referred CPJ to the Kenyan police, the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA), which investigates police violations; and the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions for comment.

A representative who answered CPJ’s call to Anne Makori, chairperson of Kenya’s IPOA, said Makori would review CPJ’s written questions, however, CPJ did not receive a response. IPOA spokesperson Dennis Oketch also requested CPJ email questions but did not respond.

The Dubai police did not respond to CPJ’s emailed request for comment.