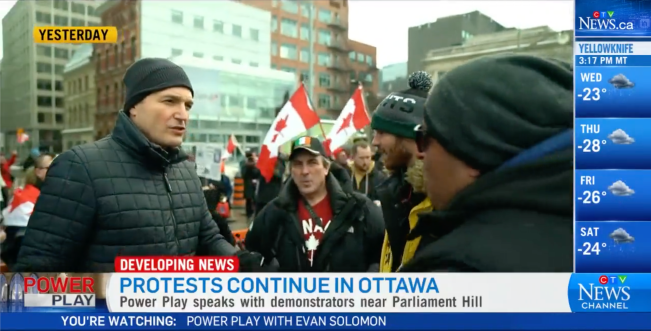

“Fake news.” “Go home.” “You’re the virus.” These are just a few of the insults that protesters have hurled at Evan Solomon, a reporter at national Canadian broadcaster CTV, and his colleagues as they have covered demonstrations against COVID-19 restrictions in Ottawa.

The protests – which began in Canada’s capital in late January to counter vaccine mandates for truckers – are now targeting border crossings in other parts of the country and interfering with supply chains, prompting Ontario premier Doug Ford to declare a state of emergency Friday.

But as reporters seek to cover these developments, they are being threatened in the streets and online. The incidents mirror the experiences of journalists in the United States and Europe, who have been shouted at and even assaulted while reporting on anti-vaccine protests.

CPJ spoke with Solomon, who also hosts a program on the radio platform iHeartRadio, and Elizabeth Payne, a reporter at the Ottawa Citizen, to learn more about the situation on the ground and what reporters are doing to protect themselves. The interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

What has it been like reporting in Ottawa?

Evan Solomon: I’m out there every day doing stand ups with them [the protesters] and speaking with them. It’s very passionate. There’s lots of yelling. You have anger and frustration at the vaccine mandates and the imposition of what many people think is an infringement on their civil rights and civil liberties. People will threaten you, people will throw things at you – that’s all happened to me. If you have a big news camera, then you’re a target. If you have a light, then you’re a target.

I would say 90 percent of the time I feel safe during the day. But any journalist out there, all of us, are almost always yelled at. “You don’t tell the full story.” “How do you sleep at night?” “You’re all liars.” [Protesters] also film you the whole time.

I’m a 6-foot-4 white guy. That’s important because a lot of these protesters are also white men. It’s hard for them to intimidate me because I’m a big person. But there are a lot of female reporters who get significantly more harassment than I do – verbal and online. They get horrific messages, dirty messages, chauvinist messages, racist messages.

On January 29, a protester threw a beer can at you. What happened?

Just before I did a live hit, as I was speaking, a guy ran up and drilled a full beer can at me and missed my head by about six inches. It hit our camera equipment, one of those big hard shell camera cases, and blew up in the case. We actually had a security guard and there were lots of police around, and the security guard saw the beer can and yelled at me to duck. I didn’t hear him though because the horns of the protest were so loud.

What steps have you taken to protect yourself while covering the protests?

Now, when [CTV] journalists are filming outside, we have to have a security person with us. We’re all using DSLR cameras, which are small cameras, so we do not bring tripods, we do not bring lights. You make sure you’re mobile in case things get out of hand. Our colleagues at CTV Edmonton have peeled off the stickers from their cars that identify them.

How does it feel to have to take these precautions?

The idea that I am a journalist in a G7 democracy, and my company says I can’t do my job without a security guard – in Ottawa, Ontario – that’s pretty remarkable.

There’s a general sense that attacking journalists is now normal. It has become acceptable to harass journalists. We saw during the Trump era the president of the United States actively saying, “You are fake news, you are the enemy of the people.” That raised the temperature in the U.S. and certainly we’re seeing it raised in a similar way here in Canada. We’re seeing an echo of it.

What do you think is fueling threats against journalists in Canada and what should be done to try to end them?

I think there’s a lot of people who do not feel represented in the media. They have not heard their own voice. And there’s been a business of peddling mistrust. There’s a war on truth and facts and doctors and scientists and governments and media. But our job is to keep hammering at the facts. Sometimes that’s very unpopular. But there’s not two sides of a fact, and we have to stick to those.

The job is to cover stories in difficult circumstances. We are in a difficult circumstance. There is not only a populist movement that has its own tools of media to counteract the established tools, but there’s a culture war based on truth and facts, there’s a heavy distrust of institutions and governments that is now part of the political process, and journalists have to cover that. The only weapons that we have are hewing closely to factual information and hewing closely to human stories that resonate.

Have you seen anything like these protests in your 35 years covering Ottawa?

Elizabeth Payne: I have never experienced this before in my city. There’s a lot of people who have been threatened. I’ve concentrated a lot of my writing on the impact [the protests] are having on people who live [downtown]. People have been calling me and begging me to take any reference that may identify them out of stories and it’s because they’re getting death threats.

These streets are generally boring and dull. So there’s a bit of a cognitive dissonance. It takes you a little longer to assess a situation as potentially dangerous. If I was somewhere else perhaps I would be more on my guard. It’s unsettling and strange.

What are your safety concerns when reporting in the crowd?

There’s a lot of potential for things to go badly. That’s what’s nerve-wracking right now: you could be out there and you could be talking to people and stuff could suddenly start to shift. You really do have to look around and make sure you have something solid behind you. You don’t just walk into a crowd without thinking about where you are and where the egress may be.

I’m also not wearing a mask. I would wear a mask right now in crowds like I’ve seen here, but my decision not to wear a mask is because it’s a provocation to these people. That makes me less safe. I’m sure I’ve been exposed to COVID many times – you’re shoulder to shoulder with people. I’m triple-vaxxed, I’ve been very, very careful over two years about not getting COVID, and it wouldn’t at all surprise me if I did during this. I could wear a mask – no one has told me not to – but it would make my job a lot harder. I would be subject no doubt to harassment.

What steps do you take to mitigate risk while covering the protests?

I don’t go out at night among the crowds. We always have the option of going with another reporter. I’m in touch before I go to find out who else is out there and where they are.

It’s very fortunate to be a print reporter. I watch broadcast reporters getting hassled all the time. But, as a print reporter, I can slide through. All I need is a tape recorder in my pocket and a very small notepad and my phone.

Have you faced any harassment – online or in the field – related to your coverage?

I certainly get a lot of Twitter harassment – people calling me vile names. It can be disturbing, but it’s also easy to delete, ignore, and block. I did get one phone call in the middle of the night that was worrisome. Someone called me a “stupid cunt.” I hung up quickly and did not feel threatened as much as annoyed and unhappy.

I believe it was during the first weekend of protests. I had written a story reporting that ambulances had been pelted with rocks and needed police escorts and that health and social workers were harassed.

How do you interpret anti-media sentiment at these protests?

Half of the signs posted along Parliament Hill [where the protesters have gathered] have to do with how the media are liars and can’t be trusted. It’s such a constant theme. Even people who are sincerely speaking to me will pause for a small rant about how everybody lies and you can’t be trusted. It’s in Canadian social media as well.

I think it’s all part of the conspiracy theories – that everybody is out to get you and the media are a part of that and people are lying to you and you can’t trust people. It’s not a side issue; it’s very much central to the belief system. In a way, I feel that by listening, I am at least doing my part to keep the lines open.