Getty Images photographer John Moore has covered crises all over the world, from the U.S. border with Mexico to political unrest in Pakistan. But the COVID-19 pandemic has found him capturing devastation closer to home: in Stamford, Connecticut, where he lives, and in the hard-hit suburbs of New York City.

Moore told CPJ about his experience covering the pandemic, and how lessons he learned while covering the Ebola outbreak in Liberia apply to photographing the coronavirus in the United States.

CPJ interviewed Moore by phone in April. His responses have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What stories related to the pandemic have you photographed so far?

In the early part of the pandemic, Getty Images sent me to Seattle, Washington, where I photographed the situation there, which included a relatively deserted downtown. I also photographed in nearby Kirkland, which has become known for the Life Care Center nursing home, where so many seniors died and so many medical personnel, doctors, and nurses, became infected during the early part of this pandemic in the U.S.

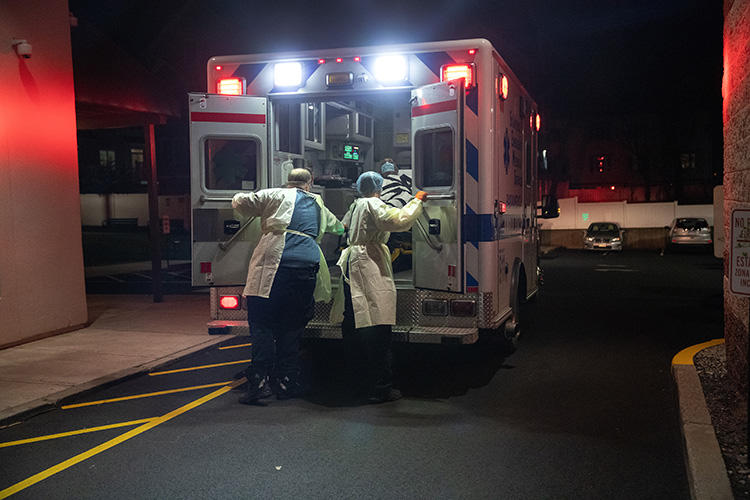

I returned after a week there, and have since been photographing in the suburbs of New York. Nationally, there’s incredible press coverage within New York City itself, but the areas around the epicenter are very hard-hit. I’ve been photographing in Stamford, Connecticut, where I live, as well as Westchester County and Long Island. I photographed in immigrant communities. I just finished a big project on EMS and paramedics in the city of Yonkers, just outside of New York City.

How have you been protecting yourself while working?

Because I covered the Ebola epidemic in Liberia in 2014, I learned a set of skills in using PPE [personal protective equipment] that I never expected to be using in my hometown, but here we are. The Ebola epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic are of course different; they affect the human body in different ways, they’re contracted in different ways.

I learned how to work in an infectious environment back when covering Ebola. I try to be very careful and follow protocols and procedures in a systematic way. That doesn’t mean that I’m fully protected and immune to this, because as we’ve seen, many healthcare workers have become sick, even when following protocols. We do the best we can when doing our jobs, and hopefully I’ll be fine.

Depending on the situation, I wear a full face respirator, two sets of latex gloves, and use plenty of disinfectant all around. I also have full-body Tyvek body suits that have hoods and footies, when the situation calls for it. I wore a Tyvek suit when I was working on Long Island, where I was photographing some immigrant families who self-quarantined when they all became sick. I was invited to visit their home. I had to assume that all the surfaces were contaminated, because it was nine people in a house. I used maximum protective PPE in that case; there were no clean zones.

I also wore a full PPE when I was traveling with EMS in ambulances with sick people. I wore a full-face respirator, gloves, and an apron, which is what [the EMS workers] were wearing. I try to match my PPE protocols to the healthcare professionals I’m working with at the time. If you wear a whole lot more than they do, you stand out too much. If you wore a full suit of body armor to a battle and everyone else just had a flak jacket on, you’d be out of place. It’s a sign of respect, that you respect the rules that they’re following.

How else does photographing COVID-19 compare to your Ebola coverage?

Access in the United States, and I suspect in the U.K. as well, is much more limited than it is in other parts of the world. Every society also has its local norms on privacy. In the case of Ebola and Liberia, many people wanted me to tell their story. They were more than happy to be photographed, because they wanted the international community to see what was happening.

I believe photojournalism—and journalism in general—early on in that epidemic did help quicken the international response, which was very slow in the beginning. We played an important role, and the public knew that too, so people were open to us telling their story, visually and otherwise.

Here with COVID-19, hospitals are generally reluctant to have photojournalists work inside, both for health and safety reasons, for legal reasons, and I’m sure it also looks very ugly in there. It’s probably to limit just how much the public sees in terms of just how bad it is. I’m sure it’s terrifying inside.

As journalists, we have to accept “No” for an answer from particular organizations, but that doesn’t mean we have to stop trying. I try to find other ways to tell the story. In this case, this last week, it was with first responders, with EMS.

What else do you think the public needs to know about photographers’ safety during this pandemic?

Our levels of risk as photographers are different than healthcare workers, of course, because they’re constantly touching people. They have to, that is their job, to treat people and to touch them. When I’m working, I’m touching as little as possible. Although I’m wearing latex gloves, those gloves are touching nothing but the camera. When I’m touching doors, I’m trying to use my elbow.

Although we do have risks as photographers, some people think going out and covering it is the same as being a medical worker. I don’t think that’s the case. I don’t want to downplay the danger, but it’s a whole different level for healthcare workers. It’s possible to cover this story in a way that has acceptable risk, both to ourselves and the people who we are photographing.

People ask sometimes, is it the same as covering a war? It’s not the same. One thing that’s constant is that we have to measure levels of risk all the time, as though we’re covering a war. For many photojournalists, the risk is not worth it, or they may not have the training to cover this story. When editors are conscious of that and respect that, I think as a profession we’re on solid ground.

Do you think photographers will have to confront trauma and lasting psychological impacts from covering COVID-19?

It remains to be seen whether that will be the case as much with this story as it is in covering conflict. When you go off to cover a conflict in another part of the world, that is not part of your daily experience. You cannot talk about that to people back home because they don’t understand. They never saw it.

Covering a crisis like this in one’s backyard, you can talk to your neighbors about it, you can talk to your family about it. You can actually talk with people who are not necessarily journalists who have been there with you.

I don’t want to downplay it, but it’s possible that this may be less traumatic than covering a war in a distant place. Time will tell, because we don’t know. But it’s relatable to the people we know.

CPJ’s safety advisory for journalists covering the coronavirus outbreak is available in English and more than 30 other languages. Additional CPJ coverage of the coronavirus can be found here.