On August 10, 2018, the Indian government informed Twitter that an account belonging to Kashmir Narrator, a magazine based in Jammu and Kashmir, was breaking Indian law. The magazine had recently published a cover story on a Kashmiri militant who fought against Indian rule. By the end of the month, Indian police had arrested the journalist who wrote it, Aasif Sultan, and Twitter had withheld the magazine’s account in India, blocking local access to more than 5,000 tweets. As of October 2019, Sultan was still in prison, facing terrorism-related charges that CPJ has repeatedly condemned. And the @KashmirNarrator Twitter account was still withheld throughout the country.

A similar pattern of multi-pronged information control has since unfolded in Jammu and Kashmir, albeit on a larger scale. In August 2019, India unilaterally revoked the region’s semi-autonomous status and shut down the internet and phone lines. Conditions for the press deteriorated, with police detaining and intimidating reporters, according to CPJ reporting. Journalists resorted to smuggling stories out of the valley on USB sticks, and CPJ has struggled to communicate with local journalists, including those operating the @KashmirNarrator account. By mid-October, the blackout was only partially lifted; some mobile phones were operational, though internet services were still suspended.

Amid the crackdown, the Indian government continued to reach beyond its borders and enlist Twitter to censor accounts sharing news and information. The legal notices it sends are not public, but the Silicon Valley social media company passes some of them to Lumen, a project of Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center, which publishes them in an open database.

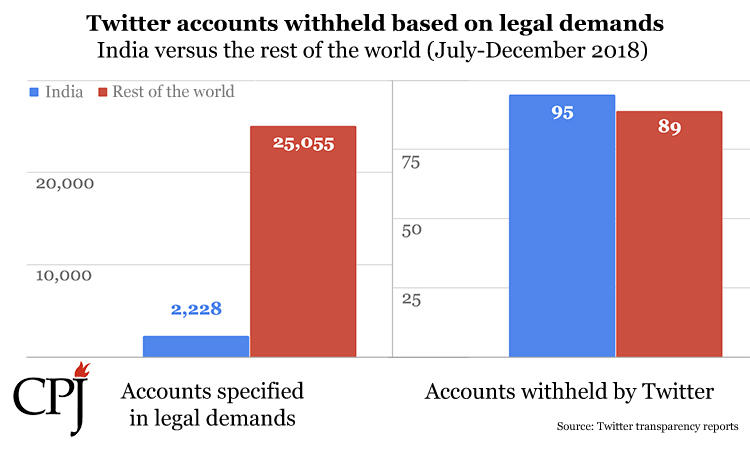

A CPJ analysis of those notices reveals that hundreds of thousands of tweets blocked in India since August 2017 under the company’s country withheld content policy were shared by accounts that focus on Kashmir. Among dozens of accounts that were withheld, CPJ identified several besides @KashmirNarrator that were sharing news and opinion, raising serious questions about what safeguards are in place to ensure freedom of the press and the free flow of information. Indian legal experts told CPJ that the requests are issued with limited oversight and transparency, leaving scant avenues for appeal. And while Twitter does not comply with every request, more accounts were withheld in India in the second half of 2018 than in the rest of the world combined, according to Twitter’s transparency reports.

Withheld content is blocked for users whose country setting or other information places them in the relevant jurisdiction, according to Twitter’s policy, which can apply to tweets or accounts. Users can still post to the accounts; among the people affected interviewed by CPJ, more than one continued to maintain them despite the blocking, sometimes in conjunction with a second handle that was not withheld. By contrast, accounts suspended for breaking Twitter’s rules against abusive behavior, like violent threats, are removed worldwide. Twitter prompts government agencies to review content for those violations before submitting notices under local laws, which have also been used to suppress journalistic content in Turkey, CPJ research in August 2018 found.

“It totally makes sense the Indian government would go after Twitter and Twitter users, because Twitter as a platform is a really significant source of information sharing, for journalists and activists and regular citizens in Kashmir,” David Kaye, the U.N. special rapporteur for freedom of opinion and expression, told CPJ. Kaye has been concerned about this trend for some time; last December, he wrote a letter to Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, asking for transparency about the company’s decision to withhold “tweets and accounts when they have participated in discussions concerning Kashmir.” Kaye received no public response, he told CPJ in August. “We don’t have any real clarity about what’s going on,” he said.

In search of answers, CPJ retrieved requests sent by Indian authorities to Twitter between August 2017 and August 2019 from Lumen. Lumen lists requests received from tech companies themselves, though it is not a complete record; Twitter says it sends requests to Lumen unless “prohibited from doing so.”

Excluding copyright notices, CPJ found 53 requests, including 13 sent by the election commission around India’s 2019 general election. The remaining 40—including the request citing the @KashmirNarrator account—were sent by the Ministry of Electronic and Information Technology. Nine of those date from August 2019 when the communications blackout in Kashmir began, a spike from the preceding months.

Combined, the 53 notices list several hundred URLs that they allege contain illegal content. CPJ analyzed every account involved, whether the request was based on a single tweet, several tweets, or the account itself, reviewing more than 400 in total. Around 45 percent of those accounts mentioned Kashmir in the handle or bio, or had recently tweeted about Kashmir, according to CPJ’s review.

Ninety-three of those accounts were withheld in India when CPJ tested them in September and October 2019. Another 29 individual tweets from different accounts were also withheld. The vast majority of the withheld accounts were from the group that referenced Kashmir, hosting over 920,000 tweets between them, CPJ found.

Twitter did not act on every request; several URLs remained accessible despite being cited, including tweets published by people listing professional media affiliations, or handles with the blue verified badge that Twitter applies to public interest accounts, according to CPJ’s review. Other accounts were suspended or not found at the time of analysis.

Assessing the press freedom impact of country withheld content based on this limited record was a challenge. Apart from @KashmirNarrator, accounts that CPJ found to be withheld in India as a result of a legal notice were not run by traditional news outlets—though some were linked to blogs or websites—but operated in a more liminal zone, straddling the lines of activism, information sharing, and commentary. Many were operated by international observers or Kashmiris based abroad.

One blocked account, Frontline Kashmir (@FKdotPK), shares a mixture of political opinions, links to news articles, videos, and accounts of developments on the ground. The Indian government notified Twitter that it was breaking Indian law on November 2, 2018, according to a request retrieved from Lumen. More than 18,000 posts shared by the account were unavailable in India when CPJ tested it in September 2019; it had over 22,000 followers at the time.

@TheVoiceKashmir, another censored account with 43,000 tweets and nearly 14,000 followers as of September 2019, shares local information and opinions anonymously, according to CPJ interviews with two of its operators. While the blog linked from the account covers international events, religious teachings, and occasional conspiracy theories, the Twitter handle serves a different function, according to its founder Ahsan Khan, a blogger with roots in the region, now based overseas, who advocates for persecuted Muslim groups.

Khan told CPJ he shares control of the account with people who live in Kashmir or regularly travel there. The account was subject to two separate legal requests in May and August 2018. It has been withheld in India for over a year, Khan told CPJ in September 2019.

People in Kashmir have “no freedom” to express themselves in daily life, Khan told CPJ. Yet, “if someone tries to come [to] social media to speak up, they will be blocked.”

A second @TheVoiceKashmir administrator told CPJ he was born and raised in the city of Srinagar, though he is now based in another Indian state. He requested anonymity, fearing reprisal from his employer for his connection with the account. He returns regularly to Kashmir to visit family, including a recent trip that coincided with the communications blackout. When he left the area, he told CPJ, he relied on Twitter to publicize what he had seen during his visit, including conditions in local hospitals and public schools, despite knowing that any tweets posted from the shared account were hidden from local audiences. “I try my level best to convey whatever message I can out of the valley,” he said.

India’s censorship process raises significant concerns, according to Indian legal experts interviewed by CPJ. Requests retrieved from Lumen that originated with the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology all cited Section 69A of India’s Information Technology Act, which authorizes government agencies to direct intermediaries like Twitter to block or remove online content on a range of grounds like security and public order.

“[Section] 69A is being misused to target journalists, and kill free expression that’s supposed to be guaranteed in the Indian constitution,” Raman Jit Singh Chima, the Asia policy director and senior international counsel at Access Now, a global digital rights advocacy group, told CPJ.

Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad, who has held the electronics and IT portfolio since May 2019, and Secretary Ajay Sawhney did not respond to multiple emails sent to addresses on the ministry’s website requesting an interview and information about censorship requests.

Government agencies seeking to limit access to online content under the IT Act must record the reasons in writing, according to Apar Gupta, lawyer and executive director of the Delhi-based Internet Freedom Foundation, an Indian digital rights organization. However, the requests are “not public, so we don’t know whether they comply with the specificity of legal regulations, which are already problematic,” he told CPJ by phone. Mishi Choudhary, the legal director of the New York-based Software Freedom Law Center, described the process to CPJ as a “black hole.”

Twitter’s compliance with these requests has increased significantly since mid-2017, according to a CPJ review of the company’s transparency reports for India, which cover content removal requests from government agencies and courts, including any that trigger country withheld content. The company complied with only one request to withhold an entire account between December 2012 and June 2017, though it was asked to withhold more than 900, CPJ’s comparison of those reports reveals. From then until December 2018, however, the number of accounts specified in requests surged to 4,722. Twitter agreed to block 131 of them.

Twitter’s transparency report says just 2% of Indian requests issued between July and December 2018 resulted in content being withheld. But 95 entire accounts were affected, 51% of all accounts withheld worldwide during the same period. Transparency reports do not include the number of active Twitter users in each country, but data compiled by consumer data firm Statista puts the number of active users in India at 7.75 million, about 2.3% of the global total.

In response to CPJ’s interview requests and emailed questions about how it handles content removal requests from Indian authorities and assesses the impact on journalistic content, a Twitter spokesperson provided an emailed statement, noting that “we don’t comment on individual accounts for privacy and security reasons.”

“Many countries have laws that may apply to tweets and/or Twitter account content. There is a transparent process for governments or authorized legal entities around the world to submit requests to Twitter,” and content may be withheld in a particular country as a result, the statement said, referring CPJ to its public guidelines and legal request process. “Twitter is committed to the principles of openness, transparency, and impartiality.”

Yet experts told CPJ that Twitter is not transparent about how hard it pushes back against censorship requests. “Twitter can question the legality of the Indian government’s blocking requests at the hearing that it is entitled to under [Section 69A]. It can also invite judicial scrutiny of the constitutionality of government orders to block and take down content,” Chinmayi Arun, the founder of the Centre for Communication Governance at the National Law University, Delhi, told CPJ. “It is not clear whether Twitter is availing itself of these avenues.”

Daphne Keller, the director of intermediary liability at Stanford Law School’s Center for Internet and Society and a former associate general counsel at Google, told CPJ she believes that that Twitter should “push back” if a government is asking for something that’s inconsistent with human rights. “But that’s expensive, and hard, and may cause them to lose a bunch of money,” she said.

Twitter is not the only social media company that has failed to publicize how it navigates local laws. In 2018, citing leaked documents, The New York Times reported that Facebook’s internal guidance for India and Pakistan referenced “locally illegal content,” and instructed moderators to apply special scrutiny to accounts that used the phrase “Free Kashmir.” At least four operators of Kashmir-related Twitter accounts being withheld in India told CPJ that they had migrated to the platform from Facebook, believing it would allow more open discussion.

“In the absence of transparency, a conclusion that the [tech] companies are acting as an adjunct of government policy is warranted,” David Kaye told CPJ.

One frustrated user is the writer Ahmed Bin Qasim. Born to separatist leaders in Indian-administered Kashmir, Bin Qasim, who now lives in Pakistan, has written columns for the Pakistani newspaper The Express Tribune and Turkish state news outlet TRT World, including a December 2018 piece about celebrating his 19th birthday while his parents were in jail. A legal request retrieved from Lumen cited Bin Qasim’s Twitter account for breaking Indian law on January 3, 2019; in September, CPJ found the account was withheld in India. “My own people don’t have access to my account,” Bin Qasim told CPJ in October.

And for those trying to get information out of the Valley, the censorship can feel particular stifling. “In Kashmir, the Indian government wants whatever news there, to stay there,” @TheVoiceKashmir administrator from Srinagar told CPJ. “If they snatch social media away from us—where else can we share our voice?”

Editor’s note: CPJ tested the status of URLs retrieved from Lumen requests in September and October 2019 and compiled the metadata returned by Twitter’s API, which reveals whether or not it was withheld in India, in a public spreadsheet. The spreadsheet includes a handful of other Kashmir-related Twitter accounts that CPJ selected for testing based on interviews, media reports, or an Indian parliamentary official’s own tweet.

CPJ Asia program’s Aliya Iftikhar and Kunal Majumder contributed reporting. John Emerson, an independent developer and designer, contributed scripting and research. Adam Holland, a lawyer and project manager at Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center, contributed research.

Avi Asher-Schapiro is CPJ’s research associate for North America. A former staffer at VICE News, International Business Times, and Tribune Media, Avi has also published independent investigative pieces in outlets including The Atlantic, The Intercept, and The New York Times. Ahmed Zidan, CPJ’s digital manager, previously worked as social media editor of Radio Netherlands Worldwide, reporter and contributor to the Arabic desk at RNW (Huna Sotak), and editor of ArabNet. He was the editor of Mideast Youth, which won the 2011 Best of Blogs award from Deutsche Welle. Follow him on Twitter @zidanism. His public PGP encryption key can be found here.