Beirut, September 10, 2019 — The Committee to Protect Journalists today condemned Iraqi Kurdistan authorities’ detention and deportation of Spanish freelance journalist Ferran Barber and urged the authorities to allow local and foreign journalists to do their jobs freely.

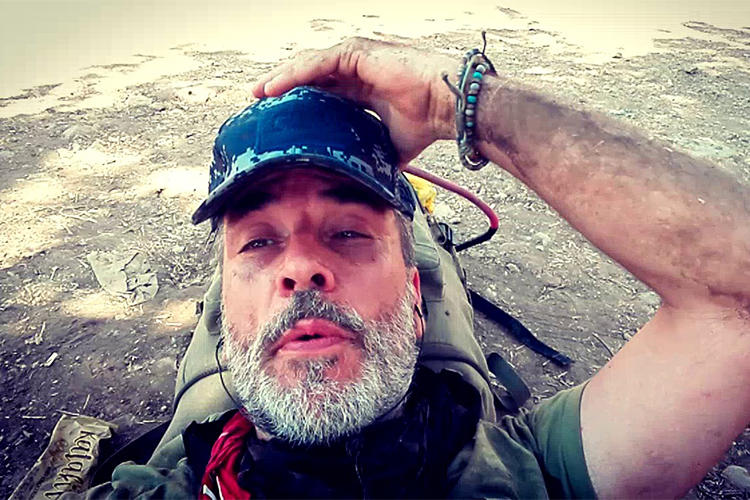

On August 8, in the Nahla Valley, in northwestern Iraqi Kurdistan, Kurdish Asayish security forces arrested Barber, a freelance reporter and photographer who contributes regularly to Spanish outlets including Publico and El Mundo, and detained him until September 4, according to the journalist, who spoke with CPJ via messaging app, and news reports.

Authorities in Iraqi Kurdistan did not file any charges against Barber and barred him from contacting anyone during his detention, including a lawyer, he told CPJ. He was deported to Egypt on September 8 and returned to Spain on September 9, he said.

“Holding a journalist for nearly a month without charge and denying him his legal rights are textbook examples of repressive dictatorships, far from the democracy that Iraqi Kurdistan claims to be,” said CPJ Middle East and North Africa representative Ignacio Miguel Delgado. “We call on the Iraqi Kurdish authorities to allow local and foreign journalists to do their jobs without fear of arbitrary arrest.”

Barber was en route to interview a jihadist in Kurdish-held northeastern Syria for a story when he encountered a Kurdish soldier who said he would take him to a nearby taxi, he told CPJ. The soldier instead brought Barber to Asayish agents who identified themselves as border police and took him to an Asayish station in the city of Akre, he said.

At the station, agents interrogated Barber in Kurdish and made him sign a document in Arabic, despite the journalist not understanding either language, and then put him in a cell, he said.

On August 9, authorities transferred Barber to an Asayish facility in Erbil, where he was detained with more than 130 people in a cramped holding area, he told CPJ. Barber said that Asayish agents interrogated him multiple times about his work and seemed to doubt his assertions that he was journalist. He said he showed interrogators his press card and passport, and they repeatedly asked him if he had alternative fake passports.

Asayish agents searched Barber’s cell phone, camera memory cards, and laptop, and did not allow him to contact his family or ProSieben, the German broadcaster for whom he was on assignment, he said.

On September 4, a representative of the Kurdish Foreign Ministry met with Barber and told him that he had been imprisoned for illegally crossing a border within Iraqi Kurdistan between areas held by Kurdish authorities and areas held by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party militant group, and was to be deported, he said. The representative told Barber he was barred for life from returning to Iraqi Kurdistan, he said.

Barber was then released, and authorities returned his laptop, phone, and other reporting gear; he left Iraq on September 8, he said.

“How can I be accused of illegally crossing a border that is within the territory of Iraqi Kurdistan? That makes no sense,” Barber told CPJ. He said he did not receive any documentation of the allegations against him or the travel ban.

Dindar Zebari, the Kurdistan Regional Government’s deputy minister for international advocacy coordination, a government spokesperson, told CPJ via email that authorities detained Barber on August 8 because he was seen in an area that had been the site of Turkish airstrikes, and said that Barber’s presence there “was of suspicion and concern and required investigation.”

Zebari told CPJ that the investigation was delayed because of the Eid Al-Adha holiday, and maintained that Berber was “treated very well” and was visited by the honorary Spanish consul in Erbil during his detention.

Berber disputed Zebari’s account, saying he was not visited by the honorary consul, and that he was held in cramped and crowded conditions.

A spokesperson from Spain’s Diplomatic Information Office told CPJ in an email that the office could neither confirm nor deny the honorary consul’s visit, citing data protection laws. CPJ emailed the consul’s office for comment but did not receive a reply.

Authorities in Iraqi Kurdistan have arrested journalists, sought criminal defamation suits against critical outlets, and raided news stations in recent months, according to CPJ research.

[Editor’s note: This article has been updated to include Zebari’s response and the response from Spain’s Diplomatic Information Office.]