Those with deep pockets can go to great lengths to push back against journalism they find objectionable. Billionaire Peter Thiel deployed a team of lawyers in a move that bankrupted the news site Gawker in 2016–and last month President Donald Trump’s lawyers tried to block the publication of an unflattering book. But there’s another, much less public, arena where the wealthy can combat unflattering reporting: the world of subterfuge-for-hire, where private investigators work to undermine a story before it’s even made public.

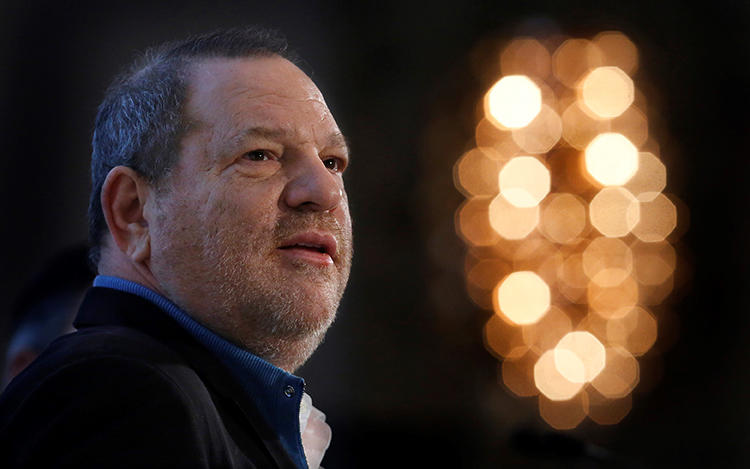

In late 2017, the public was privy to a rare glimpse inside this world. Ronan Farrow, in a New Yorker exposé, reported that movie mogul Harvey Weinstein’s lawyers at Boies Schiller Flexner had enlisted a team of private investigators to push back against reporting into dozens of sexual assault and rape allegations against their client. One of the private investigation firms, BlackCube–an outfit staffed with former agents of the Israeli intelligence service, Mossad–was ordered in a contract obtained by The New Yorker to “completely stop the publication” of an article critical of Weinstein. BlackCube ultimately failed. But, Farrow’s report found, journalists investigating Weinstein at The New Yorker, The New York Times, and New York magazine, and their sources, were approached by undercover agents with fabricated backstories, as part of an elaborate effort to keep Weinstein’s alleged sexual misconduct secret.

Weinstein’s spokespeople have denied the allegations against him and rejected claims that he tried to “suppress” any journalism. BlackCube has repeatedly insisted that it “applies high moral standards” to all of its work, and in an interview a member of its advisory board expressed regret for its relationship with Weinstein.

While there are no laws against lying to a reporter or their sources, or conducting public surveillance of or pushing embarrassing information about a journalist–as long as that behavior doesn’t veer into libel or slander–the Weinstein story raised questions about how far some will go to kill a negative story–and what, if any, ethical and legal guardrails exist to protect journalists

Of course, the use of underhanded tactics to derail a reporter is nothing new. Bethany McLean, a business reporter who broke the Enron story in 2001, recalls receiving multiple phone calls from individuals who said they were potential sources. These calls, she told CPJ, amounted to sloppy sting operations: those on the other line would try to lure her into admitting she wanted to financially benefit from her own reporting–McLean said she assumed she was being taped.

For most reporters, however, pushback usually comes in the form of aggressive public relations firms or, on occasion, threatening letters from their subjects’ lawyers. Weathering an undercover operation has not typically been part of a journalists’ job description. George Freeman said that in nearly 30 years as a lawyer for The New York Times, he “can barely think of an example” of these tactics. He is now executive director of the independent advisory group the Media Law Resource Center. “Unfortunately, it’s becoming less rare in the last couple years,” he told CPJ. “And that’s what’s scary about it”

Subjects of journalistic scrutiny are, of course, entitled to defend themselves. And for those with the resources to do so, there are plenty of techniques that reporters with whom CPJ spoke said they have come to expect, including compiling publicly available information that could reveal a reporter’s conflicts of interest, or a dossier of past reporting mistakes.

The Weinstein story revealed a more aggressive toolbox apparently used by private investigators: the impersonation of sources and hiring reporters as agents. Other cases involve deploying aggressive surveillance, and smearing sources or reporters by spreading potentially damaging personal information.

Before Weinstein, another high-profile case alleging attempts to suppress reporting focused on Roger Ailes, the founder of Fox News. Ailes’ biographer Gabriel Sherman, citing sources inside Fox, alleged that the executive used a portion of Fox’s budget to pay for a “Black Room,” where PR and surveillances operations against Ailes’ perceived enemies–including reporters–were coordinated.

Ailes, who died in May, denied the allegations at the time. On the record, Fox executives insisted to Sherman that they had no knowledge of company money being spent on surveillance or online attacks against reporters.

But, Sherman said, sources inside of Fox told him a different story. “From my own reporting, inside Fox, I know Ailes had hired private investigators to have me surveilled,” Sherman told CPJ. “It adds a level of psychological intimidation, if you know your subject has goons out there looking for you.” Sherman recalled one particularly chilling incident while he was working on his biography of Ailes: he and his wife noticed a black SUV lurking outside a cabin they were renting–when they tried to approach the car, it peeled out and raced away.

Beyond laws against stalking, assault, and fraud, there’s little to prevent the rich and powerful from deploying such tactics to suppress reporting they don’t approve of, said Philip Segal, the founder of Charles Griffin Intelligence, a private investigations firm. Segal is an expert on investigative ethics and gives ethics seminars to state bar associations.

He said he believes private investigators should follow strict ethical guidelines and refrain from impersonation tactics. Investigators should not, he said, pay other journalists to gather intelligence for them, unless those reporters are prepared to broadcast that they are not working in their capacity as a reporter.

Getting a clear picture of the scope and breadth of these aggressive private investigations is difficult. “Out of a thousand cases, I’d say one or two involved a reporter,” Randy Torgerson, the president of the United States Association of Professional Investigators, an organization with over 600 members, told CPJ.

And, when a reporter is the apparent victim of such an operation, it can be difficult to definitively trace the source. In the BlackCube case, Farrow was able to publish a copy of the firm’s contract with Weinstein. But more often than not, obtaining such a document is not possible, leaving reporters with a mixture of circumstantial evidence, suspicion, and the assurances of their own sources.

Lee Fang, an investigative journalist at the Intercept, who has reported for a number of outlets about the sprawling political network funded by the conservative Koch brothers, said he suspects operatives working for the Kochs hacked his private account on the image hosting site Photobucket and circulated an image of him smoking marijuana as a teenager.

The image published by the conservative website the Washington Free Beacon, in a post titled “High Times at The Intercept” that mocked the publication’s decision to hire Fang, was taken from a password protected account, Fang said. The Free Beacon was co-founded by Michael Goldfarb, who previously worked as a crisis communications consultant for the Kochs.

Fang told CPJ he can’t definitively prove who was behind the hack, but said that his reporting had been flagged by pro-Koch Brothers operatives before, including on a now-defunct website, KochFacts.com, that listed journalists writing critically on the Kochs’ political activities.

“There’s a healthy return on investment for intimidating reporters,” Fang told CPJ. “It can go a long way, editors can be skittish, and all you have in this business is your reputation.”

The Free Beacon did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment on how it obtained the images.

In her book Dark Money, an investigation into the Koch’s political network, New Yorker staff writer Jane Mayer alleged that the brothers retained New York City Police Commissioner-turned private investigator Howard Safir to delve into her past. Mayer wrote that sources told her Goldfarb was involved in that work. She said she also discovered that a dossier erroneously accusing her of plagiarism was passed around conservative D.C. media circles–a reporter with the conservative Daily Caller website even contacted her editors at The New Yorker, accusing her of plagiarism. She was able to quickly refute the allegations before they were made public.

The Koch Brothers have called Mayer’s reporting inaccurate, but did not directly refute the accusations when contacted by The New York Times in 2016. Safir did not respond to CPJ’s request for comment.

This kind of treatment can be particularly chilling for reporters without the institutional backing of a major publication. Roddy Boyd, the president of the Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation, says that last year he was lured to London with a job offer, only to be pumped for information about his reporting on an insurance company AmTrust. “It was really shady,” he told CPJ. “It makes you wonder; what won’t they do.”

Some investigative campaigns however, have run into legal trouble. Back in 2006, the California Attorney General found that private investigators hired by Hewlett Packard to trace leaks to the press had targeted the phone records of nine journalists. Hewlett Packard’s general counsel resigned and a court sentenced one of the investigators to three months in jail for identity theft.

In the wake of the Weinstein scandal, his lawyer David Boies expressed some regret. He said that he did not select the private investigators that Weinstein hired, or direct their work–although his signature appears on the BlackCube contract. “It was not thought through,” Boies wrote in a public statement explaining his decision to facilitate Weinstein and BlackCube’s relationship. “And it was a mistake. I take responsibility for that.” There’s no indication he or BlackCube broke any laws or will face any censure (although, The New York Times reported that BlackCube lacked the proper license to do business in New York).

[EDITOR’S NOTE: David Boies chaired CPJ’s annual International Press Freedom Awards in 2012. He and his law firm, Boies Schiller Flexner, have both donated to CPJ.]

Still, lawyers who retain private investigators are bound by a fairly strict code of professional ethics. According to the American Bar Association’s model rules for ethics, lawyers cannot engage in impersonation or false representation. They are also required to oversee the work of private investigators they may retain–and can be held responsible for ethical breaches of subcontractors.

“There’s no question the rules of professional conduct govern lawyers in all the lawyers’ activities on behalf of the client, and that certainly would include retaining a third party to work in the client’s interest,” Dennis A. Rendleman, the ethics counsel in the Center for Professional Responsibility at the American Bar Association, told CPJ. “The lawyer has an obligation to supervise and make sure that’s done in accordance with the model rules in each licensing jurisdiction. Getting positive press could be part of their job. But that needs to be done in accordance with the rules.”

In New York, Attorney Grievance Committees are charged with enforcing these ethical guidelines and disciplining lawyers. These committees, and similar mechanisms in other states, could provide a route to pushback against aggressive investigators–or at least, the lawyers who employ them. “To the degree that law firms are involved in this, you may try to use the bar disciplinary system to rein in lawyers who are involved in such activity,” said Kathleen Clark, an ethics expert and law professor at the University of Washington Law School.

The committee charged with overseeing lawyers in Manhattan declined to comment to CPJ on any potential investigation into Weinstein’s lawyers, or speak on the record about any past instances of lawyers facing discipline for their work with private investigators.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: The third paragraph of this blog has been updated to reflect BlackCube’s comments on its work.]