Even as the country collapses, South Sudan’s government will brook no criticism

By Jacey Fortin

JUBA, South Sudan – The shooting began around 5:15 on a Friday afternoon.

Dozens of journalists had gathered in the pressroom at the Presidential Palace–a walled compound also known as “J1”–in the capital city. Following a few days of rising tensions, culminating in a checkpoint shoot-out just the night before, the president, Salva Kiir and the vice president, Riek Machar, former wartime rivals, were expected to hold a news conference calling for peace.

The journalists had been waiting for a couple of hours when they heard gunfire outside. Most of them dropped to the floor. A woman working security by the door fumbled with a gun she didn’t seem to know how to operate, making everyone nervous.

After about an hour, the shooting subsided and Kiir and Machar finally appeared, first to urge calm following the gunfire, about which they professed to know little, then to give prepared speeches about the state of the nation.

It was the day before the fifth anniversary of South Sudan’s independence.

The journalists waited for hours until it was deemed safe to leave J1. Around midnight, they piled into the beds of pickup trucks and were escorted by soldiers back to a hotel. None were hurt. Some had spotted bloodied corpses on the pavement as they made their way out of the gates.

“The incident at J1,” as it has become known in government parlance, marked a new era for South Sudan. The world’s youngest country has had a succession of such eras, beginning in 2005, when decades of war against the armed forces of Sudan ended and a fledgling southern government was supposed to be laying the framework for a new state.

Then came 2011, when a landslide referendum created an independent nation. High-ranking officials in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, or SPLA, set themselves to the task of building a nation – a daunting task for a group of war veterans who had made a career of armed struggle.

December 2013 saw the beginning of a civil war that would kill tens of thousands and displace millions, pitting those loyal to President Kiir, a member of the Dinka ethnic group, against those loyal to former Vice President Machar, a member of the Nuer ethnic group. Amid the upheaval, censorship efforts only worsened, with the government often equating criticism with opposition sympathies.

In April 2016, in accordance with a peace deal, Machar moved back to Juba to resume his post as Kiir’s deputy so that the two could preside over the formation of a new transitional government.

That arrangement grew increasingly tense. After clashes erupted at J1 in July, they spread across the city, killing hundreds. Machar and his troops were forced out of town. He remains in exile, while skirmishes outside the capital continue, reminiscent of the civil war that was supposed to have ended.

***

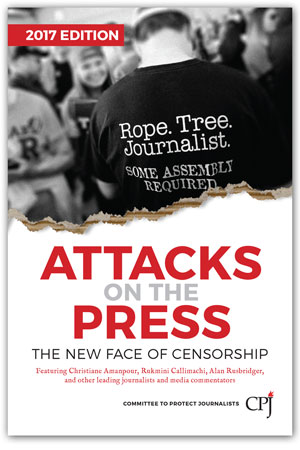

With each passing era, the state of press freedom and media censorship has only gotten worse. Even during peacetime, there was a concerted effort to thwart the establishment of a free press in the nascent country: Journalists faced arrests, outlets suffered shutdowns, and media protection laws were ignored. But war has only made things worse, creating an atmosphere of increased militancy and fear. Journalists know that an article deemed to be criticizing the president or his cronies could cost them their freedom or even their lives. Government workers have been known to appear at printing presses to excise newspaper articles that are deemed offensive. Even the U.N. has made it difficult for journalists to access key information.

Things have never been easy, observed Emmanuel Tombe, deputy director of Bakhita Radio, a community station in Juba. Like so many other local media organizations, Bakhita’s first challenge has been simply to stay afloat in a dismal economy. It is a daily struggle even to cover the basics such as staff salaries, studio equipment, and generator fuel.

Bakhita is first and foremost a Catholic station, with an emphasis on family-friendly sermons and religious hymns. But it also had three English-language shows dedicated to current events, so it has not been immune to government intimidation, threatened shutdowns and even attacks on staffers in the years since its founding in 2006.

“With the conflict right now, the media is even more threatened,” Tombe said in August 2016. Not only did insecurity make it harder to get community funding, it also caused the station to tone down its political reporting, including shutting down “Wake Up Juba,” a morning show that sought to engage government leaders in discussions about local problems. The show touched on everything from low-level corruption to political upheavals. In another concession, the station stopped taking outside callers to ensure that no one stirred up controversy on-air.

“The station could be shut down or taken to court; Anything could happen,” Tombe said. “We also have to worry about the presenter of the program. If the presenter is at risk, his safety can be ensured when he’s within the office. But when he’s home, what will happen? Nobody knows.” For now, lying low strikes Tombe as the best way to protect his staffers and keep the cash-strapped station afloat.

By mid-July 2016, it had become clear that the government, having pushed Machar’s troops out of the city, seemed all the more eager to clamp down on free speech, especially after its soldiers committed a fresh wave of brutal human rights abuses against civilians. That has forced some journalists to self-censor, for fear of provoking a government whose military has never shown respect for media freedoms. Other journalists, both local and foreign, have chosen to leave the country altogether.

One of the most experienced foreign correspondents in South Sudan, freelancer Jason Patinkin, left the country in August 2016. He had just filed a story for The Associated Press documenting a gruesome rape epidemic, mostly committed by SPLA soldiers against Nuer women. “Given the sensitivity of the story I wrote, which was heavily attacked by these pro-government trolls online, whom many believe are on the payroll of the government, I didn’t feel safe,” he said. “So I left, and I still don’t necessarily feel safe going back.”

But escape is not an option for everyone. “Of course South Sudanese journalists face far, far greater risks and greater restrictions than foreign journalists,” Patinkin said. “The things they put up with for their belief in the truth about South Sudan has my deepest honor.”

***

“This is my country. I know people who fought and died for this country,” said Hakim George Hakim, a South Sudanese video correspondent for Reuters. “And I believe that the only difference between a journalist and a soldier is that we are fighting with our pen and our opinion, while the soldier has a firearm.”

Hakim says that both the government and the opposition are deserving of criticism. But his opinions have gotten him into trouble many times. From what he can tell, the blowback comes not in response to his professional work, but to the views he expresses on his personal Facebook page, which are mostly general posts about how journalists should not be targeted and how the government and the opposition are both failing the people. His professional work–mostly videography for a newswire–cannot serve as a platform for his opinions, but he is dedicated to vocalizing his thoughts on social media to push for peace in South Sudan.

In 2016, someone broke into Hakim’s parked car and took only an envelope of personal documents. He has been trailed by government vehicles more than once. He has been warned that his name had been placed on a no-fly list at Juba Airport. He has received dozens of anonymous phone calls asking him to take down certain Facebook posts.

Some of those calls threatened violence. “Somebody would call me and say, ‘Do you want your family to cry soon? About losing you?'” he said.

Not all media workers who lost their lives in 2016 were targeted for their work. Kamula Duro, a cameraman working for President Kiir himself, died of gunshot wounds during the clashes in July, with no suggestion that he was intentionally targeted.

Shortly thereafter, a journalist working for the international organization Internews was gunned down while sheltering in a hotel compound on the outskirts of Juba. John Gatluak had been working for Internews for four years, and was by all accounts a thoughtful, professional and notably dedicated journalist. The scarification on his forehead identified him clearly as a member of the Nuer ethnic group, and Internews believes it was this alone–not Gatluak’s work–that singled him out for a summary execution on July 11, 2016.

Still, there is no question that journalists’ work has put them at risk. At a press conference in August 2015, President Kiir made a statement that has lived in infamy ever since. “The freedom of press does not mean that you work against your country,” he said. “And if anybody among them does not know that this country has killed people, we will demonstrate it one day on them.”

Four days later, the newspaper journalist Peter Moi was shot dead by unknown assailants as he walked home from work. And in December 2015, newspaper editor Joseph Afandi was arrested and detained for nearly two months, possibly in connection with an article criticizing the SPLA. In March 2016, just weeks after his release, Afandi was abducted, severely beaten and dumped near a cemetery in the capital.

“They try to terrorize you and scare you,” Hakim said. “We have many examples in South Sudan. When somebody doesn’t like what some journalist did, his boys, or his gang, can execute the plan of eliminating that journalist. It happens a lot.”

Asked about these incidents, the government simply denies that any problems exist. “There is no harassment,” said Information Minister Michael Makuei. “These stories about intimidation have been concocted. Otherwise, they should have reported it to us at the ministry.”

But media workers here know that the information ministry is not a safe space. Foreign and local journalists alike are sometimes summoned there to be berated–at length–by ministry officials and intelligence agents who accuse them of producing stories that are biased against the government.

***

Sometimes, the summons comes not from the information ministry but from the security and intelligence agency–and that, journalists know, is a sign of trouble.

It happened to Alfred Taban, who is perhaps South Sudan’s most celebrated and well-known journalist. For decades, he worked in the restrictive media environment of Khartoum, Sudan. But when his country first achieved independence in 2011, Taban moved south to become the founder and editor-in-chief of the Juba Monitor, which is now South Sudan’s most prominent English-language daily newspaper.

In all this time, Taban has never been afraid to write articles critical of the government. But things took a turn when, after the clashes, he wrote an opinion piece calling for both Kiir and Machar to step down. On July 16, 2016, the editor was called to the intelligence agency and then put behind bars. He would not be released on bail until two weeks later.

“[Officials] used to call me to their offices and complain about my articles, and somehow we would reach an understanding,” he said, sitting in his office behind a desk stacked high with old newspapers. “But this time, without any warning, they just threw me inside. So this was really a clear sign they were not interested in dialogue.”

Despite suffering medical problems, including diabetes, high blood pressure and a malarial infection, Taban was initially refused admission to a hospital. That changed when he requested a different doctor, one who was not in league with the security officials. He was released from jail shortly thereafter.

Upon returning to the office, he quickly discovered that the government had other ways to censor his work; plainclothes security agents were going to the private printing press where Juba Monitor is produced and demanding certain articles be cut.

He pointed to the August 4, 2016, edition of the paper, where a big blank spot took up nearly half the page. That was supposed to be a news report about Pagan Amum, an SPLA veteran now critical of the government, who had called for a team of technocrats to take over the country’s administration. But the security agents had removed the article and asked the printers to place an advertisement there to fill the space.

Taban intervened by removing the ad, knowing that blank spaces can speak volumes. “The purpose is to let the people realize that there is very serious censorship,” he said.

Taban says South Sudan’s media environment has never been worse. But one good thing came from his time in detention: He got the rare chance to speak, face to face, with George Livio.

Livio had been working as a radio journalist employed by the U.N. Mission in South Sudan, or UNMISS, when he was arrested in the western town of Wau on August 22, 2014. He has been detained for more than two years with no formal charges filed against him. (CPJ has never been able to determine a link between his imprisonment and his journalistic work and has not included him on its annual prison census).

An official with the intelligence agency, Ramadan Chadar, said in August 2016 that he had never heard of Livio’s case. He said Oliver Modi, the head of the Union of Journalists in South Sudan–a nominally independent media organization–might have more information. Modi knew of the case, but said that it was “a security issue” in the hands of the intelligence agencies.

In this way, both men–each referring the problem to the other’s organization, even as the two sat right next to each other–wiped their hands clean of the issue.

Taban said that Livio was sharing a small cell with three other inmates in a compound where dozens of men had access to a single toilet and were fed once a day. It was almost always the same dish: beans with too much salt, Taban said. Livio also told Taban that UNMISS had not been allowed to visit Livio for months.

“The treatment of these people was what disturbed me. I was not so much thinking about myself; I was thinking about them. Because the accusations against them are ridiculous,” Taban said, adding that most had been accused of working with the opposition.

***

Even Livio’s own former employer has remained quiet. UNMISS has not once publicly called for his release, and officials, when pressed, always insist that they are working on it behind the scenes. “We are raising the issue of [his] release over and over again with the relevant authorities,” said UNMISS head Ellen Margrethe Loj in May 2016.

To date, that method has failed Livio, and many journalists here aren’t surprised. UNMISS has a strained relationship with the media in South Sudan, having shown reluctance to relay essential information or even to allow journalists access to its displacement camps across the country.

Freelance journalist Justin Lynch took a U.N. flight to visit one such camp, in the northern city of Malakal, in February 2016. He happened to touch down in the middle of a vicious attack. Men wearing SPLA uniforms had stormed the camp, killed civilians and burned down tents. When all was said and done, at least 25 people had lost their lives.

It was clear that the U.N. peacekeepers had utterly failed to protect the displaced, only stepping in when it was far too late.

Almost immediately after Lynch landed, officials at the UNMISS Public Information Office ordered him to leave, but other U.N. staffers encouraged him to stay. “On the night of the 17th, the U.N. made a statement saying the attack was done by ‘armed youth,'” he said. “And I think a lot of people at the U.N. Mission in Malakal were really angry, because we knew it was the SPLA, and we knew that the peacekeepers had fled.”

With help from these sympathetic staffers, Lynch repeatedly dodged U.N. officials who were trying to track him down and put him on an airplane.

“Whenever you block access like that, it’s conducive to a closed environment where these kinds of problems can fester,” Lynch said. He stayed at the camp for five days and eventually published a series of reports–many of which were published by the Daily Beast–that challenged UNMISS’s version of events and exposed the peacekeepers’ failures. In December 2016, he was deported from South Sudan.

Patinkin agrees that in a country where censorship is already rife, the U.N. doesn’t make things any easier. He said the situation has gotten worse with time, citing a host of obstacles including U.N. staffers’ refusals to report clashes, restrictions on access to the camps, and arbitrary price hikes for U.N. flights.

“I have even been yelled at by UNMISS spokespersons,” he added. “I mean, the level of unprofessionalism from the UNMISS PIO has at times been shocking.”

***

Incidents like these only add to an atmosphere of censorship in this war-torn country. And no matter where the censorship comes from, it is not only journalists who suffer; it is the entire population, which came together with so much hope when South Sudan became a nation in 2011. When local outlets are afraid to voice criticism, the U.N. restricts access, newspapers are subject to the whims of security officials and talented journalists see no option but to leave, there is a gaping void of information that the government is keen to fill with its own propaganda.

The journalists here do what they can, but the trauma of reporting in a country like this wears them thin. For some, the fatigue is palpable. The foreigners come and go, leaving the country when it becomes too difficult or too dangerous. The locals flee when they are able, though sometimes they have nowhere to run to.

In the view of video journalist Hakim George Hakim, someone has to stay to fight for South Sudan’s great potential. Hakim believes that someday, generations from now, a peaceful country will look back on these early years with a sense of relief that the worst is over.

“Now the country has reached a level where the government knows that the people know that this is a failed state,” he said. “And they don’t want anybody to talk about that. So if you try to criticize the government’s performance, you’re going to get some problems.”

But he says he’ll keep trying anyway, no matter what.

Jacey Fortin is a freelance journalist who reports from Ethiopia and South Sudan.