A journalist details one fight over records requests in the United States

By Michael Pell

In December 2010, Robin Gordon faced an ultimatum. She had found that a debt collection company had purchased a $291 tax lien on an apartment she owned in Atlanta, Georgia, after her mortgage company failed to pay a small portion of her Fulton County taxes five years earlier. Now, she could either pay the debt collection company $8,200, a 2,700 percent increase, or the sheriff’s office would auction her apartment to pay the debt.

Eventually, Gordon’s mortgage company agreed to pay, but for the Atlanta Journal Constitution, her experience raised a host of questions. How many tax liens had the Fulton County Tax Commissioner sold to private companies over the years? Who bought them? And how many people lost their homes over small bills and clerical oversights?

At first, an official from the tax commissioner’s office said they couldn’t answer any of these questions because they didn’t track lien sales.

Days later, an attorney representing Fulton County said they did track lien sales using a property transaction database maintained by the tax commissioner’s office.

And so began the parry-and-thrust dynamic of a two-year records battle that saw the county employ some of the most common tactics used by government agencies across the United States – and the globe — to frustrate records requests.

Freedom of information laws, which include the right to file requests under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in the U.S., are increasingly popular around the world, even in some fairly repressive countries, because they represent good PR regarding transparency and open government. Theoretically, at least, such laws ensure access to public records, yet their practical utility can be thwarted through bureaucratic foot-dragging, what are essentially dumps of reams of useless documents that are impossible to sift through, or exorbitant fees.

Though the Fulton County battle took place in 2010 and 2011, it remains an extreme example of a practice that has become widespread, which has the effect of killing stories by making access to the necessary public records significantly difficult, if not impossible.

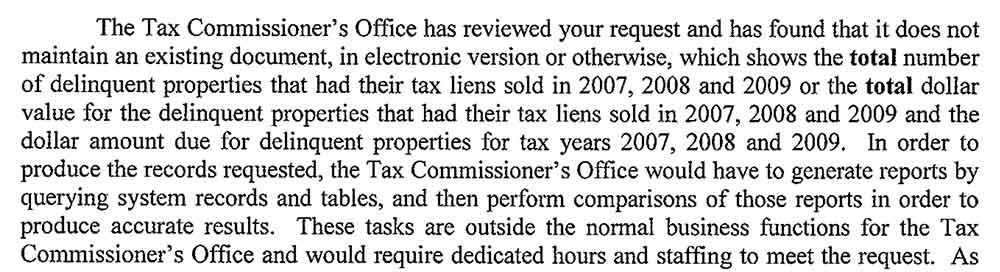

In December 2010, while working for the Atlanta newspaper, I requested county records detailing the number of liens it had sold. The county denied the request on the grounds that there were no records responsive to the request, essentially saying that while the tax commissioner knew how many liens were sold each year, the information had never been committed to a report, email, or any other written document.

In response, the newspaper (typically known by its acronym, the AJC) issued a request in January 2011 for the tax commissioner’s entire property transaction database.

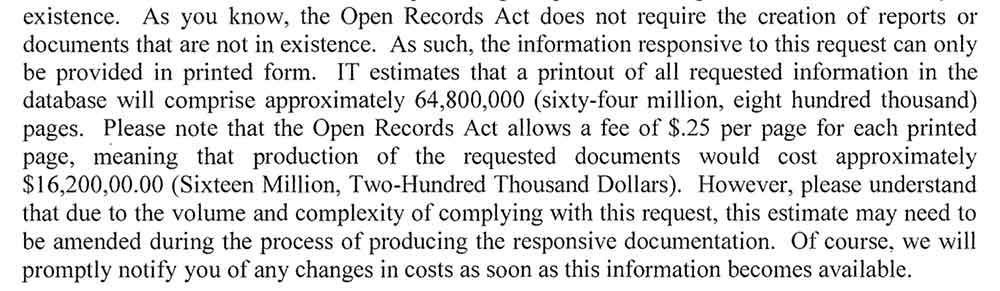

Later that month, Fulton County came back with a cost estimate for processing the records request. Government agencies often use inflated and vague processing fees as a barrier to access, knowing the modern media has a limited budget to purchase records, but Fulton took the tactic to an extreme.

The county attorney’s office said they would have to print each record from the database. At 25 cents a page, it would cost the AJC $16.2 million for the 64.8 million records. Parry.

Not only is the cost an insurmountable barrier, but Fulton would only make the records available in paper, a format that made any meaningful analysis impossible. Providing records as paper or a PDF is another common practice for government agencies looking to stymie access to public records.

While this would be enough to permanently stall many records requests, the AJC lobbied the Georgia legislature to strengthen the state’s open records law and close loopholes like those that allowed state agencies and municipal governments to deny requests for digital records.

After bolstering the open records law and using open records requests to learn the name of the database and the name of the company that developed it, the AJC submitted a new records request in May 2012. Thrust.

Days later, Fulton County denied the request yet again, this time claiming that releasing portions of the data were trade secrets of the software company. Parry.

At the nexus of government and private business interests, this is another common and potentially fatal response to a records request.

But the AJC filed a complaint with the Georgia attorney general’s office and convinced them to get involved. Ultimately, it was only the threat of a lawsuit from the state attorney general’s office that compelled the Fulton County Tax Commissioner’s Office to turn over the database two years after the initial request.

An analysis of the database revealed that one company purchased $350 million worth of liens over a 10-year period. The data also showed the company received favorable treatment from the tax commissioner’s office. The tax commissioner sold the company liens when other companies were told liens were not for sale and helped the company make up to $20 million in additional revenue by allowing the company to charge property owners a 10 percent penalty that would otherwise be collected by the county.

“It’s very unfortunate that it took so much time to do what was right and it’s very unfortunate that it took a letter saying that suit would come within 10 days,” then-Attorney General Sam Olens told the AJC in 2013. “That’s not the way the Open Records Act is supposed to work.”

Michael Pell is a reporter on Reuters’ data team who covers topics ranging from healthcare fraud to workplace safety.