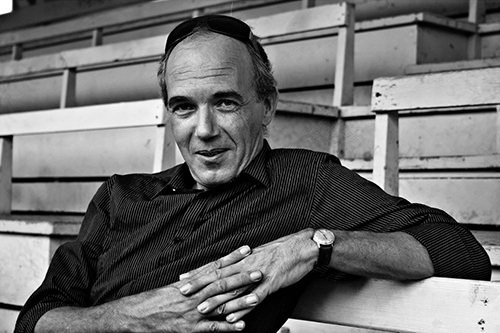

A faint smile appears on Okke Ornstein’s face as he recalls what happened last summer, when he traveled with a group of refugees through Europe to document their trip for a Dutch radio broadcaster.

“When we finally reached Germany, I was kept apart and interrogated by the police. They thought I was a human trafficker. It took an hour of phone calls to the radio studio in Hilversum to convince them I was a journalist,” he said. “That’s where I expect problems, you know. Or like when I was covering the war in Syria or when I boarded a plane with all kinds of weird things in Beirut. But not here.”

Ornstein, who was arrested at Panama airport November 15, is set to serve a 20-month sentence for criminal defamation. A Canadian businessman, Monte Friesner, filed the suit against him in 2012, over reports Ornstein published about him on his website, Bananama Republic.

The journalist initially faced up to 38 months in prison because of an 18-month term handed down in a separate defamation case. That sentence was commuted to a US$3,500 fine on November 30, according to Ornstein’s Panamanian lawyer, Manuel Succari, and has since been paid. When I met with Succari in Panama City early December, he told me he is trying for a commutation or reduction of the 20-month sentence.

Ornstein is currently in Renacer prison, about a half hour’s drive from the capital. It’s a low-security prison that houses several high-profile prisoners, including Manuel Noriega and a former Supreme Court judge. When I visited on December 3, the Dutch journalist looked relaxed and said he was doing “better than he thought he would.”

“The circumstances here are actually not that bad. Within the Panamanian context this is one of the better prisons, and I am in one of the best buildings,” he said. The low cell block where he is being held could be seen from the prison visiting area. “It’s kind of like a very cheap hostel that should have been closed down 10 years ago, but somehow still keeps operating. And of course you’re not free to go wherever you want to go and there’s not much to do here. We’re not allowed to have cell phones and there’s no internet access,” he said.

Over the past few weeks, Ornstein’s case has garnered international attention, especially in the Netherlands, where the respected reporter has a long career producing in-depth reports for NPO, the country’s public broadcasting system. His detention led CPJ and other organizations, including the Dutch Association for Journalists, to criticize Panama’s criminal defamation laws.

Convictions of criminal defamation in Panama carry fines and prison sentences of up to 18 months. By virtue of those laws, Panama has the distinction of being one of only three countries from the Americas to feature on CPJ’s 2016 prison census of journalists jailed for their work.

Panama has partially decriminalized defamation, including a constitutional amendment that prevents public officials imposing fines or prison sentences of those deemed to have insulted them, a comparative study of defamation laws in the Americas, prepared for CPJ by the law firm Debevoise & Plimpton in collaboration with the Thomson Reuters Foundation, found. A May 2007 reform to the criminal code made defamation of public officials an act no longer subject to criminal penalties.

But the reforms do not offer protection for journalists such as Ornstein.

The journalist told me he is the victim of a slow and dysfunctional judicial system, which was why he was able to move freely for years after his convictions. Ornstein said he was never properly informed of the sentences and was only vaguely aware of what steps he could take to appeal.

“They also never facilitated an interpreter. I wasn’t going to give any statements in Spanish, because I speak street Spanish, but to follow legal proceedings in Spanish is a whole different ball game and I don’t feel comfortable doing that,” he said. “But they from the beginning always refused to provide any kind of interpreter, even in English.”

The Panamanian Public Prosecutor’s Office did not respond to CPJ’s requests for comment.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs said, in a December 1 statement, that it was working with officials at the Netherlands embassy in Panama on Ornstein’s case. It added that Panama has updated its criminal defamation legislation and was committed to respecting freedom of expression and human rights.

Panama’s efforts to reform defamation laws were echoed by Manuel Domínguez, the presidential spokesman, during a meeting with CPJ’s Americas program director Carlos Lauría. Dominguez said the government was doing everything in its power to assist in Ornstein’s case.

For Ornstein, being imprisoned in Panama is a strange turn of events. The reporter arrived in Panama in 2000 to interview a jailed Dutch drug lord and decided to stay, driven by the desire to witness changes in the wake of the country gaining control of the Panama Canal in 1999.

“You have a few of these places that become really international, like the south of France, Tokyo and maybe Mexico City,” Ornstein said. “Panama could have become like that.”

Ornstein spends long periods of time in Panama, where he has a 13-year-old daughter and, prior to being jailed, regularly traveled abroad to cover major events like the war in Syria and the European refugee crisis. “That’s my real job, doing long-form radio reports on these issues,” he said.

[Reporting from Panama City]