It’s a calm day in a Ugandan village. Women gather on plastic chairs, shaded from the afternoon sun. I’m here with a handful of journalists on a reporting trip sponsored by the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF). The village women welcome us and begin to tell us about their lives. Then something happens. A man in the shadows glares at us. Others begin to crowd around. There is tension. We are not wanted here.

They come from all directions, waving canes and bamboo poles. We run. They chase. We sprint around a building, toward the far side of the village as the mob closes in. There’s a wall, and we can’t jump it. We have no choice but to turn and face the gang.

My heart pounds: It’s us-with notebooks, cameras, and recorders-against a dozen villagers with sticks. I grab my colleague’s hand and we brace our bodies for impact, barging through the horde and running toward our car. All of us make it out unharmed but rattled.

This is all a test, part of hostile environments training for women journalists, conducted by Global Journalist Security (GJS). The anger isn’t real, and neither is the mob. But almost everything else is-the Ugandan sunshine, the IWMF reporters, the women, the sticks, the wall, and the pounding in my heart. It’s all meant to be an exercise in dealing with sudden dangers and unexpected attacks, in this case with the specter of villagers in a conflict-ridden society who are suspicious of our activities as journalists. Though the mob and village women are actors hired by GJS, and the reporters hail from multiple countries, with the largest contingent from the United States, when I see that wall and turn to face the mob I have unexpected flashbacks of riots I’ve covered in Southeast Asia. As a journalist, I’ve faced gunfire, robberies, a grenade attack, government surveillance, detainment, and deportation. But until now I had never been trained to cope with any of that.

* * *

At the time we underwent our training, nine months into 2015, the year already ranked among the deadliest on record for working journalists. By the end of the year, at least 71 journalists were killed in direct relation to their work, according to CPJ research. In more than two-thirds of those cases, the journalist was singled out for murder.

“Journalists today face more threats to their physical safety because they have become targets,” said Lily Hindy, deputy director of Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues (RISC) “Before they were in danger simply because they were close to it and could be caught in the crossfire; now they are sought out specifically.”

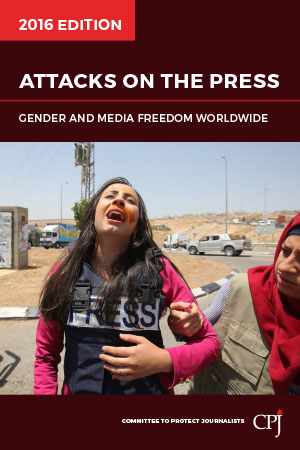

Female journalists face certain dangers such as sexual assault and sexual harassment far more often than men, which is why gender-specific security training such as the IWMF hosts is becoming more widespread and increasingly viewed as essential.

In 2014, IWMF and the International News Safety Institute (INSI) published “Violence and Harassment Against Women in the News Media,” billed as the first comprehensive report on threats to women journalists around the globe. “Nearly two-thirds of survey respondents said they had experienced some form of intimidation, threats, or abuse in relation to their work, ranging in severity from name-calling to death threats,” IWMF Executive Director Elisa Lees Muñoz told me in an email interview. Most of those incidents were never reported, and most “occurred in the workplace rather than on assignment.” Still, many women reported incidents of physical violence-pushing, shoving, assault with an object or weapon-that happened in the field while covering protests, rallies, or public events. More than 14 percent of respondents said they’d experienced sexual violence related to their jobs; nearly half of all respondents said they’d endured sexual harassment.

“Women are at greater risk of being sexually assaulted than men, both by individual and group male attackers, as well as by sexually aggressive mobs,” said Frank Smyth, GJS executive director and CPJ’s senior adviser for journalist security. It is unclear whether those risks have increased, he said, “or if women and men among the press corps have recently brought more attention to the issue by finally talking about it.”

The issue gained global attention in 2011 when a mob sexually assaulted CBS News correspondent and CPJ board member Lara Logan, who was covering the uprisings in Egypt’s Tahrir Square, a notoriously dangerous place for reporters. British journalist Natasha Smith recounted a similar incident. And in 2013, a Dutch journalist was raped while covering protests in the same location. They aren’t alone: photojournalist Lynsey Addario described her kidnapping and assault in Libya in gripping detail in her memoir, It’s What I Do.

Many journalists have said enough is enough. And they’re acting.

“We made the decision that wherever possible we would offer hostile environments training to any women with whom we work,” IWMF’s Muñoz said. “We believe that it is our responsibility.”

That includes the GJS training that puts me in a make-believe mob in Uganda. It is one of several role-play scenarios-kidnapping, car wreck, shootings, grenades, sniper attacks-we work through individually and as a group.

* * *

“We will push you out of your comfort zone,” Smyth tells us on Day 1 of our training. But, he adds, “we do not want to traumatize you.” Unlike life, I can stop any activity, anytime, by simply raising a hand.

Our three-day course covers everything from emergency first aid to weapons to digital security. I will always remember “DR. ABC”: Danger, Response, Airway, Breathing, Circulation. If a colleague is shot in front of me, or a stranger is bleeding from a traffic accident injury, I now know the initial steps for administering emergency aid before seeking help.

As a reporter, I developed early on an instinct for situational awareness-assessing the scene around me, from a broad to narrow perspective. But I admit, I’ve been lax about formalities: a risk assessment to be conducted before a reporting trip, a communication plan to develop with friends or relatives before departure, and a proof of life document that contains confidential information that can be used in worst-case scenarios to confirm whether a person is still alive. (Examples of these forms and a full scope of journalist safety information can be found online through CPJ’s Journalist Security Guide and the Rory Peck Trust.)

“Look at the worst-case scenario and then prepare for it,” said Judith Matloff, a longtime foreign correspondent who offers journalist safety training independently and through Columbia University. “I started covering stuff in the 80s,” she said. “Journalists were targeted then. And the risks were immense, but there’s an awareness now. We didn’t have advocacy groups, we didn’t have training groups, we didn’t have anything. Our editors would give us like a bottle of scotch and say good luck.”

There are far more resources today, but they could be better, Matloff said.

“Very few people actually offer training for women, and it’s something that I think has been ignored for too long,” Matloff said. Many hostile environments courses are run by men with military training “and what they do is they throw a sack over somebody’s head… and say this is what it’s like to be kidnapped,” she said. “It doesn’t prepare you for good decision-making. What it does is it teaches you what it’s like when the s*&t hits the fan.” Her training focuses instead on how to avoid those situations in the first place.

Though training is key, it is also important to carefully vet the training program itself, Matloff said. In some cases male trainers have too closely mirrored the perpetrators women need to avoid, she said. “I’ve spoken to countless women who’ve been hit upon or sexually harassed by the male trainers,” she said. “Military men tend to foster a very gung-ho boys’-own type of environment that women don’t feel that easy with, so already you’re starting out in a situation where women are outside their comfort zone.”

Smyth agreed that security trainings designed by the “Western military mindset” aren’t the best fit for most reporters in the field. “Journalists and NGO workers are unarmed civilians who are constantly navigating among authorities or others with guns. This requires a broader and more nuanced skillset than traditional military training would provide,” he said. Global Journalist Security treats sexual assault sensitively, but openly. Men and women are included in GJS trainings because “both women and men must be part of the solution,” he said. “There has long been a taboo about the subject of sexual assault, and whispering about it in small groups only feeds the stigma surrounding it.”

Indeed, Matloff said, that stigma prevents many women from talking about an assault after it happens. “There’s also the shame that somehow you are a bad professional,” she said. “These women feel really, really isolated.” And they often don’t tell their bosses, “particularly freelancers-they’re afraid they’re not going to get sent on assignments.”

The IWMF/INSI survey confirmed this. “I never reported it. To whom should I report? The same person who intimidated me is the same person to whom under normal circumstances, I was to report,” one Cameroonian journalist commented (the survey did not include respondent names).

Another, an American, wrote that she suffered the consequences of reporting on-the-job harassment to her supervisors. “I was the one sent home and removed from my normal responsibilities. Quickly the investigation turned on me.”

Many respondents said they suffered both physical and psychological pain from work-related assaults. Some started using a pen name. Others dropped particular stories. Some permanently moved or gave up journalism entirely. As a result, threats against women journalists are often, ultimately, threats against public information.

* * *

Prevention is key-that’s one of the primary lessons in safety training. And often, it comes down to you. “You have no choice but to take care of your own security,” Smyth said.

Matloff talks about an experience she had while reporting in Burundi. She’d met a key source, a military official, who wanted to take her out after curfew. “I just knew-I had that uh-oh feeling,” she said. She didn’t go out with him. “I didn’t get the story, I lost him as a source, but I wasn’t raped,” she said. “We have to make these difficult choices that men don’t. A guy could have just gone out drinking with him and it would have been fine.” Women must take greater precautions. “Everybody goes down to the bar in the hotel at night,” she said. “You’ve got to be really careful. People slip drugs in your drink, you get drunk… you can’t react quickly if you’re drunk.”

And if something goes wrong, it’s critical to have a plan for dealing with worst-case scenarios, Matloff said.

Such questions should also be asked by people with whom the reporters work, she said. “It’s a discussion that has to take place in the newsroom before women go out,” Matloff said. “The whole industry should be aware of it.”

Unfortunately, independent journalists tend to be even more isolated. “Freelance media workers are sometimes at additional risk doing their jobs, as they have none of the institutional resources or support afforded employees of a news organization,” according to the IWMF/INSI report.

“Freelance safety is up to both the freelancers themselves and the publishers of their work,” said Hindy of RISC. “It is irresponsible for a freelancer to go into a dangerous area without doing a thorough risk assessment, getting prepared through training and carrying the right equipment. It is equally irresponsible for an editor/publisher to pay a freelancer less than they need to safely carry out their assignment, and not ask the right questions about how prepared they are to be doing that assignment. If a freelancer is not trained and a publisher wants to take their work from a conflict zone, we think they should help pay for them to be adequately prepared.”

How effective is preparation? “We measure success several ways: by both the direct and anonymous feedback we receive from trainees immediately after classes, by the stories trainees have told about how they have successfully applied the training lessons later in the field, and by our steadily increasing roster of both news and NGO clients,” Smyth said.

Freelance reporter Roxanne L. Scott, a 2015 IWMF fellow who participated in security training in Kenya before reporting in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, said her training changed her approach to danger. “Even when I’m not working, I’m always aware of my surroundings,” she said. “For example, when I used to get in my car, I’d sit for a while sending text messages, sometimes with the windows opened. The security training taught me there is a risk that someone can walk by and grab my phone out of my hand or try to open my door. So now, when I get in my car, I start it and drive off as soon as I can. I also learned to know who is around you. If I’m in a dark area, I always look around to know who is around so I’m not caught by surprise.”

Matloff said she’d like to see hard data on the most useful kinds of security training for women journalists. “I can’t give you statistics,” she said. “We need to do an industry-wide survey to see what type of training is useful, other than anecdotally.” And she believes the survey should come from a neutral, nonprofit source. “It’s really hard for a trainer to do that, to allow a really, really thorough analysis of data, of whether what they’re doing is effective,” she said. “I feel any time that profit gets involved, when you’re providing a service, it muddies the situation.”

* * *

That afternoon in Uganda, when the test-mob closes in, I am thinking of protests I have covered in Cambodia. I am thinking of moments I wished I could back-pedal through time, to change my steps and avoid the scene entirely.

And yet: That wouldn’t work. Even if I could reverse the clock, I’d still probably end up facing the mob-the real mob. As a journalist, it’s my chosen job to be where the story is-which is, at times, a risky place. And no training can diminish that impulse in me.

“It’s the nature of our profession that we’ll never fully be 100 percent safe,” said independent journalist Molly McCluskey, a 2014 IWMF fellow who went through security training in Uganda before reporting in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. “Preparation and training help mitigate the risk, but as long as we’re in the field, asking questions that people don’t want answered, we’re going to be in varying levels of danger. To feel more secure, I would have to change professions entirely.”

* * *

A few safety tips for journalists of any gender from security training programs, individual experience and the IWMF/INSI report:

- Conduct a risk assessment before entering a potentially dangerous zone

- Develop a communications plan for checking in with key contacts while in the field

- Prepare a proof-of-life document to be used in case of kidnapping

- Understand the language around you, or hire someone who does

- Stay near the edge of large crowds; avoid the middle

- Always have an escape route

- Research local hospitals before traveling

- Have an evacuation plan

- Know how you will store your information and how you will get it out of the country

- Understand how your work affects the safety of sources, fixers, and local journalists

Karen Coates is a senior fellow at Brandeis University’s Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism. She traveled to Uganda and Rwanda on a 2015 International Women’s Media Foundation reporting fellowship.